Hanging by a Thread—The Red Sea Blockade and Jordan's Fragile Garment Industry

Houthi attacks have revealed an industrial paradox.

Houthi attacks have revealed an industrial paradox.

On a Tuesday morning, Farnaz and her Bangladeshi female colleagues crouched in a line against the crumbling back wall of their worker dormitory in Ad-Dhulayl—the sprawling town adjacent to one of Jordan’s largest industrial zones for export-oriented clothing production.

It was April 2024, and the women should have been at work in the two-story factory across the road where they sew sports and outdoor clothing for large US brands like Timberland and The North Face. Instead, they were forced to take annual leave because their factory’s warehouses were empty.

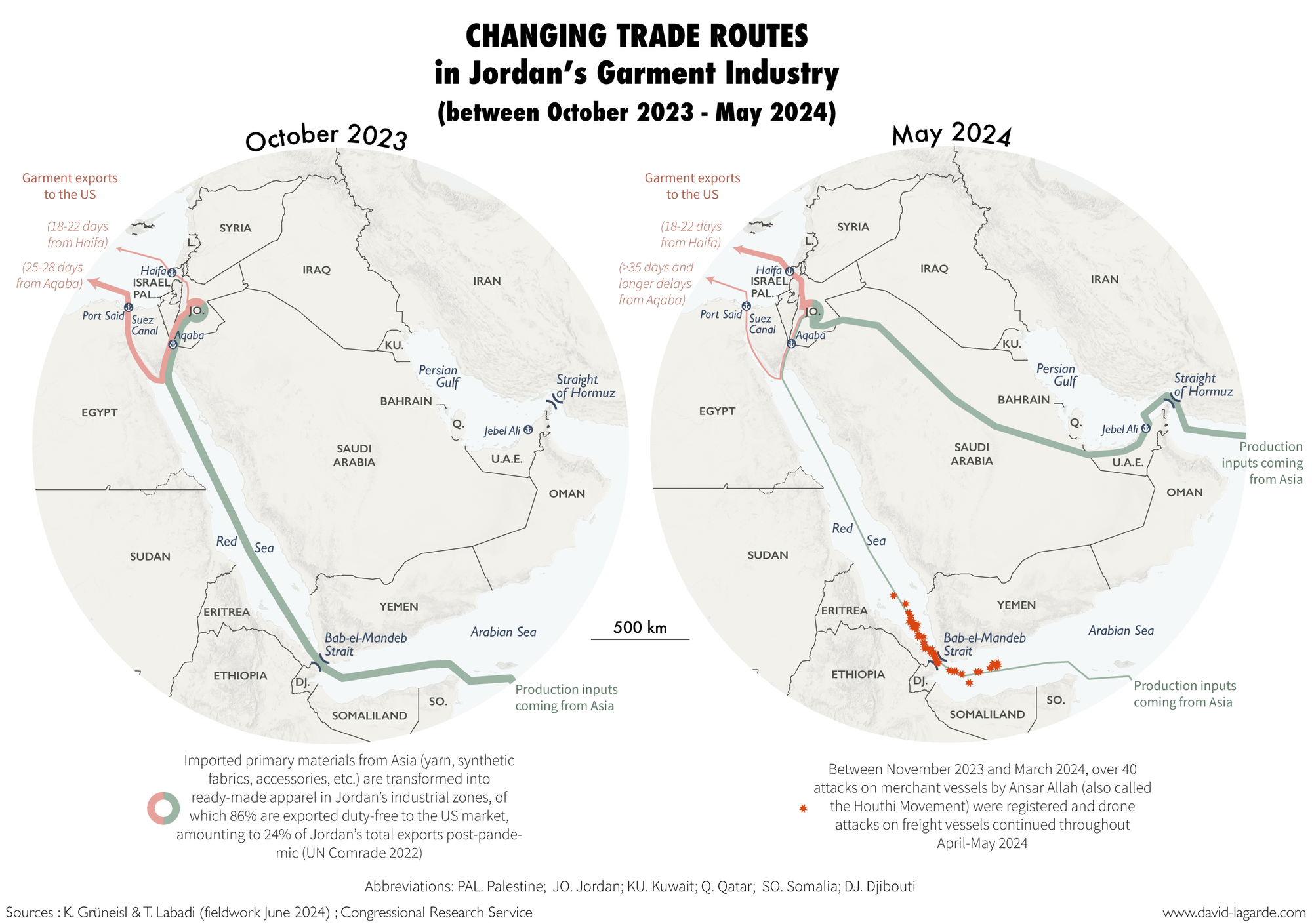

Similar scenes played out across Jordan’s industrial zones during the winter and spring of 2024. Ongoing attacks on military and merchant vessels, first launched by the Yemeni Ansar Allah (Houthi) movement on November 19, 2023 in response to Israel’s brutal onslaught on Gaza following the Hamas attacks of October 7, had hampered the transit of raw materials needed for the garment industry. As vessels were hijacked or damaged by missile attacks in the Bab Al-Mandeb Strait (the maritime gateway to the Suez Canal) many shipping companies rerouted their vessels around the Cape of Good Hope. Their rerouting isolated Aqaba—Jordan’s only sea port, which sits on the Red Sea—from key international trade routes, resulting in supply chain disruptions. Jordan’s clothing industry, the country’s largest industrial export sector besides phosphates and potash, was particularly hard-hit due to its precarious positioning in the global garment value chain.

Indeed, the regional conflict has exposed the underlying problems with an industrial garment sector that was created through preferential trade agreements granted by the United States in the wake of the 1994 peace accords between Jordan and Israel. While Jordan’s export-oriented garment industry has since been heralded as a success story, the sector remains structurally vulnerable to supply chain shocks. Garment producers located in Jordan are not only dependent on the import of raw materials and migrant labor to ensure profitable production, they also rely on orders by large US clothing brands that rapidly switch suppliers if the Jordanian factories fail to deliver in time.

But while the garment sector is a fragile geopolitical creation, kept afloat by powerful alliances of political and economic interest, it has nonetheless come to play a pivotal role in neoliberal visions of transforming Jordan’s economy. Beyond the initial project of promoting political normalization with Israel, today the garment sector assumes crucial importance in Jordan’s performances of economic stability and global competitiveness.

Since its inception, Jordan's garment industry has been wholly dependent upon fragile trade networks tying local producers to markets halfway across the globe. On one end, the industry is structurally dependent on importing the materials needed to produce garments, including fabric, accessories and machinery. These inputs are mainly sourced from China but also come from India, Pakistan and Taiwan. On the other end, the sector is completely dependent on the United States as an export market, where a few powerful US clothing brands are its core buyers.

The sector owes its existence to the Qualified Industrial Zones (QIZ) agreement, a preferential trade deal offered by the United States to foster regional economic integration in the wake of the 1994 Jordan-Israel peace accords.

The sector owes its existence to the Qualified Industrial Zones (QIZ) agreement, a preferential trade deal offered by the United States to foster regional economic integration in the wake of the 1994 Jordan-Israel peace accords. The 1996 QIZ scheme was an add-on to the US-Israeli Free Trade Agreement from 1985. It extended quota- and duty-free access to the US market to products manufactured in designated industrial zones, under the condition that at least 8 percent of the value added was derived from Israeli inputs.[1] To satisfy this condition, most garment producers in Jordan imported packaging material like cardboard and plastics from Israel.

In 2001, the United States signed a full Free Trade Agreement with Jordan, JUSFTA, which entered into force in 2010. The new agreement dropped the requirement for Israeli inputs, allowing all “Made in Jordan” garments to enter the US market duty-free. Synthetic fabric (used for sports and outdoor clothing), in particular, is heavily taxed upon entry to the United States. JUSFTA thus provided a crucial incentive for Asian garment producers of these goods to relocate parts of their production facilities to Jordan. Since the mid-2000s, the majority of garment factories in Jordan are part of transnational companies headquartered in East Asia, often Hong Kong and Taiwan, which also operate production facilities across South Asia, most prominently in Bangladesh and Vietnam.[2] Until today, around 90 percent of garments “Made in Jordan” are exported to the United States.[3] Attempts to diversify export destinations, especially to Europe, have so far largely failed.

The agreements were signed in the name of promoting prosperity and stability in Jordan. But the export-oriented garment industry that emerged as a result remains dominated by foreign capital, migrant labor and the decision-making of powerful supplier firms and clothing brands. Even before the Red Sea blockade, the industry’s over-dependence on global supply chains and acute susceptibility to external shocks was apparent. During the COVID-19 pandemic, lockdowns in China along with container shortages deprived Jordanian factories of vital production inputs, while US buyers cancelled orders in anticipation of a sudden drop in consumer demand.

In November of 2023, Houthi missile attacks began to deter shipping companies from sending their vessels into the Red Sea to reach the Israeli Red Sea port Eilat or to access Israel’s ports on the Mediterranean through the Suez Canal. The blockade also isolated Jordan’s only sea port in Aqaba, resulting in the delay or non-delivery of production inputs, most importantly fabrics and accessories ordered from East and South Asia.

At first, garment producers in Jordan relied on emergency stocks. By the first quarter of 2024, however, many factories were forced to interrupt production. Production managers and logistics officers recount how they sought to cope with these supply chain disruptions by sourcing production materials locally, mainly from Egypt and Turkey. But without access to high-quality accessories and synthetic fabrics and constrained by strict quality criteria of US buyers, most producers were unable to replace inputs.

Producers in Jordan also tried to diversify import routes from Asia. Some factories resorted to air freight, particularly for small accessories like buttons, zippers or printed labels. They also re-routed imports through the Emirati sea port Jebel Ali and then by truck through Saudi Arabia. But congestion at Jebel Ali, a shortage of trucks and the Saudi forwarding rule—which obliges transporters to unload and reload the contents of shipping containers before crossing the border—caused transport time and costs to spiral. Incidentally, not only production input materials, but also food imports for the over 58,000, mostly South-Asian migrant workers employed in the factories, have been rechanneled through Jebel Ali.

News of the Red Sea blockade prompted some US brands to pre-emptively shift orders from Jordan to other production locations in Asia. Adidas cancelled orders before their supplying factory in Jordan had even failed to meet the agreed production deadlines. “It was so frustrating,” Asma, a young Jordanian logistics officer of a Taiwan-owned sportswear factory explained. “We had received the fabric but were forced to shred it entirely because Adidas felt it was too risky to let us go forward with the production and gave the order to our group’s factory in Cambodia instead.”

While the Red Sea blockade pushed large producers to shift production volumes back to Asia, those limited to production facilities in Jordan continued manufacturing at a loss, negotiating extra leeway with their US buyers or using air freight to get their shipments to the United States in time.

While the Red Sea blockade pushed large producers to shift production volumes back to Asia, those limited to production facilities in Jordan continued manufacturing at a loss, negotiating extra leeway with their US buyers or using air freight to get their shipments to the United States in time. Suresh, a South-Indian manager of a factory in Ad-Dhulayl, recounted using air freight twice in the spring of 2024 to avoid delays in shipments to his US clients. Justifying his decision, he stressed, “just-in-time delivery is crucial to the sports brands we work with, and the penalties they impose on us for delays are much worse than the loss we make through the increased transport costs.”

Some smaller factories subcontracting for larger clothing exporters have started to produce for the local market despite reduced profit margins. Others have closed down temporarily. Many of the workers in these subcontracting workshops are migrants who have overstayed their visa and thus work informally and are paid at piece rate. With the suspension of production, they were simply let go without prior warning or compensation.

As spring turned to summer and Houthi drone boat attacks on vessels continued to pose security risks for shipping, inflating insurance costs for entering the Red Sea, a growing disquiet took hold of the garment industry. Jordan’s only competitive advantage as a global garment production location, namely duty-free market access to the United States, was now eclipsed by a connectivity problem. But this problem predated the Red Sea blockade.

In the spring of 2023, less than one year before major shipping lines suspended their service to Aqaba in light of the Houthi Red Sea blockade, Jordan celebrated the inauguration of a faster shipping service to the United States.

The launch event was proudly hosted by the American Chamber of Commerce. The new connection cut sailing times between Aqaba and the east coast of the United States to 25 days. Instead of sending a feeder vessel into the Red Sea to Aqaba that would then reload merchandise onto a larger vessel in another Red Sea port, like Jeddah, Hapag-Lloyd had agreed to send a mother vessel continuing directly for transshipment to the Mediterranean and then on to the United States. The introduction of this faster shipping service was the hard-won result of years of diplomatic efforts, aimed not only at promoting exports to the United States, but also at convincing garment producers to export from Aqaba rather than Israel’s port of Haifa.

The celebrations, however, proved ephemeral. In June 2024, port employees of the Aqaba container port testified to a drastic reduction in trading volumes since the onset of the Red Sea blockade.[4] An employee of the Danish company APM Terminals that manages the Aqaba Container Terminal (itself a subsidiary of the multi-national shipping and logistics giant A.P. Moller-Maersk), told us we were lucky to see a container ship on the day we interviewed him. “We often go for days now without a single one coming in,” he said, pointing across the piers from the port’s viewing platform. Indeed, the neighboring Israeli sea port in Eilat, just a stone's throw away across the gulf, declared bankruptcy less than a month later, in July 2024, as a direct result of the blockade imposed by the Houthis.

But while the managers of different transport and logistics companies agree that the blockade has caused import volumes to drop, they also underline the structural under-utilization of Aqaba’s port capacities that long predated the regional war.

“The good thing about a crisis is that it gets the blame for all pre-existing problems,” the owner of a large Jordanian logistics company told us. “But the truth is that Aqaba was struggling before the Houthis, ever since it lost the transit trade to Iraq and Syria, because Jordan’s market alone provides an insufficient hinterland for a major container port.” Transit trade to and from Iraq had made up more than a third of Aqaba port’s trading volumes after the 2003 US invasion. But repeated border closures beginning in 2013, when violence escalated in Iraq and armed groups seized control of the border crossing, abruptly interrupted this transit trade. It has never fully recovered, in part because Iraq has developed its own port infrastructures and alternative logistics routes with links to Turkey.

Both the Jordanian and US governments had been lobbying for years to reroute garment exports from Haifa to Aqaba. But industry representatives confided that Haifa had remained their sea port of choice. “Ask anyone in the industry,” Bilel, a Jordanian factory manager told us as he readied a shipment of Timberland shorts in a factory on the outskirts of Amman in April 2024. “Since the war everything has shifted back to Haifa port. But in fact, Haifa has been the garment industry’s open secret from the outset, though many people refuse to discuss this openly.”

Haifa’s direct access to the Mediterranean reduced sailing times to an average 18–22 days instead of around 32–36 days from Aqaba. Since cross-border transport and export from Haifa had been an implicit part of the QIZ agreement from the start, transport from the Israeli port continued even when Jordanian-Israeli cooperation dwindled and Asian producers moved in, as faster delivery times outweighed the slightly higher handling costs in the Israeli sea port.

But while the managers of different transport and logistics companies agree that the blockade has caused import volumes to drop, they also underline the structural under-utilization of Aqaba’s port capacities that long predated the regional war.

This calculus was destined to change with the 2023 launch of the faster shipping service. The current CEO of the American Chamber of Commerce, Raghad Al Khojah, narrates how, together with the garment employers’ association JGATE, they lobbied US brands sourcing from Jordan to pressure large shipping companies to offer more direct connections from Aqaba to the United States. “The Jordanian producers don’t have the commercial weight to ask for a better service,” she explained. “But if a massive client like Walmart does it, the shipping companies are more likely to listen.” In parallel, the Jordanian Ministry of Trade and Investment secured assurances from Jordanian garment producers that they would shift exports from Haifa to Aqaba. “When the new shipping service was proposed to us, we were ready to reconsider,” Bilel said, “for us this is about a simple economic calculus, not patriotism (wataniya).”

Indeed, a major rationale for bringing “Made in Jordan” garments to Aqaba was to better utilize the port’s capacities and thus establish more lucrative maritime trade opportunities for Jordan’s stagnant economy. Even before the blockade, bombastic visions for the neoliberal transformation of the port city of Aqaba into a global hub for both tourism and trade had largely failed. The city’s governance as a special economic zone had facilitated massive privatization and weakened local political oversight, producing a fragmented urban landscape of unfinished mega-projects.[5] Rerouting clothing exports through Aqaba port was considered a political and economic priority in order “to increase movement in a structurally under-utilized port,” as one of the managers of the Aqaba container terminal told us. “Increasing trading volumes is key to attract shipping lines,” he explained, and “to mitigate the problem of empty containers piling up due to a lack of exports.”

Several ministry officials interviewed for this piece elaborated that, in addition to being of economic value, rerouting over 70 percent of “Made in Jordan” garments from an Israeli sea port was considered to be of great symbolic importance by the Hashemite monarchy, whose interests dominate the policy agenda of the Jordanian government.

A number of ministries—including those of Investment, Industry & Trade and Transport—conducted feasibility studies and undertook lobbying efforts to re-route exports to Aqaba. These moves took place in the context of a wider Jordanization strategy launched by the government in 2009–2010 to increase the political legitimacy of an industry that has remained largely external to the domestic economy. Both the dominance of foreign investors and the sector’s reliance on migrant workers had become increasingly contentious in a context of skyrocketing unemployment, prompting the government to introduce new policies. In 2012, for example, the Ministry of Labor limited the maximum percentage of foreign workers to 75 percent and encouraged producers to create heavily subsidized “satellite garment factories” in deprived regions, with the aim of fostering local female employment.[6] The government has also offered preferential access to citizenship for foreign investors, allowing them to claim that large flagship companies like Classic Fashion—the single biggest clothing producer in the Middle East and North Africa—are “Jordanian” since their Indian Founding Chairman and Managing Director Sanal Kumar was naturalized.

A senior employee of the Ministry of Investment echoed the centrality of garment exports through Aqaba to performances of a healthy economy, not just in the port, but also at the level of the national economy: “Objectively, our clothing industry does not provide for much local employment and most of its profits are repatriated to Asia. But if you look at it differently, the sector helps Jordan produce macro-economic figures that demonstrate a stable balance of trade and make us eligible for loans.”

Eligibility for loans by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund is tied to monetary stability, which is in turn closely entangled with Jordan’s capacity to export to the United States. Moreover, powerful backers like the United States have long promoted industrial development and employment, in part to reduce Jordan’s domestic over-dependence on the service sector.

Behind closed doors, US and Jordanian government and business associations are once again working hand in hand, this time to reassure US brands about the future of garment production in Jordan.

During Ramadan 2024, the US embassy in Jordan organized a meeting with prominent clothing brands in an attempt to demonstrate the garment producers’ resilience to ongoing supply chain disruptions. The French embassy in Jordan invited representatives from transport and logistics companies to discuss risks related to disruptions on the Jordanian-Israeli border crossing and to explore possibilities for alternative trade routes with foreign investors. Meanwhile, the inauguration of Jordan’s first synthetic textile mill, BIA Textile Company, by King Abdullah II in April 2024 was deliberately staged to send an optimistic message of progress in a moment of crisis. The King’s speech was broadcast live on radio and TV from the Mafraq industrial zone. It portrayed the massive investment of the garment flagship company, Classic Fashion, as a crucial achievement for enhancing supply chain autonomy in the Jordanian garment industry. These political efforts portray the Red Sea blockade as a “moment of crisis”—one detached from past and future trajectories of growth and development that place the garment sector at the heart of Jordan’s Economic Modernisation Vision 2033.

While most investors in Jordan have managed to resume production, almost all have slowed down or suspended expansion plans and many testify to new investors cancelling or postponing plans of coming to Jordan.

In the autumn of 2024, however, worries were palpable among stakeholders in the garment sector. One of their fears is that brands will shift sourcing more permanently from Jordan to Egypt, which also benefits from the QIZ agreement and thus duty-free access to the US market. While most investors in Jordan have managed to resume production, almost all have slowed down or suspended expansion plans and many testify to new investors cancelling or postponing plans of coming to Jordan.

“The longer this war lasts, the more critical the situation gets for the garment sector,” one staff member of the Better Work Jordan program (part of the International Labour Organisation) told us in November 2024. “The producers say the present crisis is worse than what they experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the heightened pressure on producers takes a toll on workers. We see it in our 2024 worker survey results.” Indeed, garment sector representatives and the Jordanian Chamber of Industry utilize the crisis to argue for preserving the industry’s exemption from Jordan’s minimum wage regulations.

Workers in Jordan’s garment factories meanwhile testify to deteriorating working conditions since the onset of the blockade. While Farnaz and her Bangladeshi colleagues in the Ad-Dhulayl industrial zone have returned to their sewing machines and production lines since spring 2024, they recount the severe mental and physical stress they have suffered due to extremely volatile production rhythms. “We are used to irregular working times, between peak and low season,” Farnaz explained, “but now there are no more seasons. Everything has become completely unpredictable.” At times, they are sent home at 3 pm without overtime working hours for weeks due to a lack of orders, reducing their salaries to a meager 110 JD ($155), the amount that remains of their monthly wage after accommodation, food and social security are deducted. At other times, orders must be met in record time, so that the workers are forced to accomplish extreme overtime, up to 12 or 14 hours a day including on their only weekly holiday.

Protesting working conditions, meanwhile, has become more difficult than ever as the Red Sea blockade has further shifted power relations on Jordanian shopfloors in favor of employers.

Speaking to us after a long day of unloading trucks and stacking imported fabric rolls in a warehouse in the Al-Hassan industrial zone, Jalal, a Jordanian worker in his early thirties, confided, “a lot of us have been forced to work unpaid overtime hours lately, and no one dares to complain because the managers say they risk bankruptcy, and everyone is scared to lose work, both the locals and foreigners who would simply be sent home.”

Jalal, whose parents were forcibly displaced to Jordan from Palestine during the 1967 war and who grew up in the Palestinian refugee camp in Zarqa, underlines the absurdity of his own position. “I feel completely schizophrenic. I mean imagine my situation. My family members are killed in Palestine, and here I am, just across the border, fearing for my job because my salary depends on an open border and trade with Israel.” His words capture a larger contradiction. The same US geopolitical interests that initially drove the Jordanian garment sector with the goal of generating a “peace dividend” are causing an existential threat to this industry by enabling and fueling Israel’s region-wide aggression.

Read theprevious article.

Read thenext article.

This article appears in MER issue 313 “Resistance—The Axis and Beyond.”

[Katharina Grüneisl is a geographer and postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Nottingham and associated researcher at the Institut des Recherches sur le Maghreb Contemporain (IRMC). Taher Labadi is an economist and a researcher at the Institut Français du Proche Orient (IFPO) in Jerusalem.]

[1] Shamel Azmeh, “Trade Regimes and Global Production Networks: The Case of the Qualifying Industrial Zones (QIZs) in Egypt and Jordan,” Geoforum 57 (2014), pp. 57–66.

[2] Shamel Azmeh and Khalid Nadvi, “‘Greater Chinese’ Global Production Networks in the Middle East: The Rise of the Jordanian Garment Industry,” Development and Change 44/6 (2013), pp. 1317–40.

[3] UN Comtrade Data for HS61 and HS62 (Apparel and clothing accessories; knitted), 1998–2022, accessed and analysed between March 2–7, 2023.

[4] “Attacks on Red Sea Ships Disrupt Jordan’s Commercial Sector,” AsharqAlawsat, January 3, 2024.

[5] Matthieu Alaime, ‘Le Paradoxe Extraterritorial Au Cœur Des Territoires Mondialisés. Le Cas de La Zone Économique Spéciale d’Aqaba, Jordanie,’ Annales de Géographie 705/5 (2015), pp. 498–522.

[6] Better Work Jordan, “Advancing Jordan’s Satellite Garment Factories,” Policy Brief, Amman, Jordan: International Labour Organization (2019).