Power Struggles—Energy as a Weapon of War, Domination and Resistance in Palestine

The role of the grid in Israel's colonial domination.

The role of the grid in Israel's colonial domination.

On October 8, 2024 less than 24 hours after Hamas carried out the October 7 attacks, Israel halted the flow of power to Gaza, instantly cutting the availability of electricity from 14 to four hours per day.

The following day, Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant declared a “complete siege” on Gaza, including electricity and fuel alongside food and water. By October 11, Gaza’s power plant had run out of fuel and stopped producing electricity altogether. On October 12, Minister of National Infrastructure, Energy and Water, Israel Katz, declared the denial of fuel, water and power would continue until Hamas released its hostages.

This war on infrastructure has led to unprecedented catastrophe due to energy’s critical role in the provision of other essential services: Desalination plants exhausted their fuel supply within a week, cutting off Gaza’s access to clean water—an outcome that Human Rights Watch has characterized as deliberate and genocidal. Hospitals lacked the electricity to adequately treat the thousands of casualties they received. The sewage system ground to a halt within a month.

But Israel’s capacity to almost instantaneously cut power to the 2.2 million people living in the Gaza Strip is not unprecedented. It is the result of a century of policy and the construction of a centralized, fossil-fueled, Israeli-controlled energy system. Palestinian energy dependence is integral to Israel’s domination of Palestinian life. It constitutes a key tool for the practices of exploitation, expropriation, siege, colonization and removal to which Palestinians have long been subjected. As Omar Jabary Salamanca has argued, through its control over electricity and other essential services, “the State of Israel is able to create the possibilities for life, but also to induce failure and death.” [1]

In the post-October 7 war on Gaza, the denial of energy supplies and targeting of energy infrastructure by Israeli forces occurred as part of a broader campaign to render the strip uninhabitable. If it holds, the current cease-fire will ostensibly require that Israeli authorities allow large quantities of fuel into the strip alongside other aid. But this provision is precisely the problem: Israel will likely retain control over the flow of energy into Gaza, and Palestinians in Gaza will therefore remain dependent and vulnerable to punishing siege tactics. Even if the end of this war brings a return to the two-state formula, rather than formal annexation, it is impossible to imagine meaningful Palestinian statehood under such conditions.

Electricity’s central role in the colonization and uneven development of Palestine extends back to the Mandate period.

In the early 1920s, British authorities awarded the Palestine Electric Company (PEC), run by the Russian Zionist engineer Pinhas Rutenberg, a 70-year monopoly concession on electricity provision throughout the Mandate territory. Jerusalem was served by a separate, British-owned concession originally granted by the Ottomans. With British support, the PEC built generating plants and assembled a network of power lines that connected military installations and areas of dense Jewish settlement to the grid, establishing an enduring relationship between energy infrastructure, occupation and colonization.

The PEC invested heavily in majority-Jewish areas on the assumption that they would enjoy greater economic growth and thus make better customers. This investment facilitated additional settlement, which in turn encouraged the PEC’s further expansion. The PEC also purchased land around sites designated for planned hydroelectric dams and power lines, including the fertile Jordan and ‘Auja river valleys. It allowed the construction of Jewish colonies to serve as defensive bulwarks around PEC infrastructure. These investments reinforced the familiar N-shaped pattern of Jewish settlement, with high-voltage wires and new villages extending from Tel Aviv in the south to Haifa in the north and the Jordan River in the east.

The PEC fought to maintain their exclusive right to electrification, preventing Arab municipalities from establishing their own local grid systems, even in locales the company viewed as unprofitable—as Fredrik Meiton has shown.[2] Palestinian communities seeking to connect to the PEC grid often faced resistance and exploitative terms. The PEC initially refused to connect the Arab town of Nazareth to the grid, for example, determining that it would be unprofitable. The company only began providing Nazareth with electricity under a novel arrangement under which the municipality, rather than the company itself, would pay the interest on the capital raised for the project.

Moreover, many Arab communities refused connection to the grid for fear of adding momentum to the colonization of Palestine. Some who opposed the PEC’s expansion and British imperial policy carried out acts of sabotage against the grid, damaging power lines and generators to cause major blackouts. But by the mid-1930s, the PEC had reduced the effectiveness of sabotage by adding redundancy to the grid. The company also made agreements with local elites to connect key Arab communities, like Tulkarem and Jenin, rendering more Palestinians dependent on PEC electricity. Though rebels regularly sabotaged PEC infrastructure during the 1936–9 Great Arab Revolt, the grid was by that time resilient enough to withstand such tactics.

Throughout the 1930s, the PEC’s tendency to invest more extensively in infrastructure that served the rapidly industrializing Yishuv produced distinct and unequal, though interconnected, Jewish and Arab economies. By the end of the Mandate, the Yishuv constituted only about a third of the population but consumed as much as 90 percent of the power generated. This disparity in electricity access reflected, and helped produce, the foundational inequality between Arab and Jewish communities that developed across the Mandate period. It also helped create the appearance of Arab underdevelopment that was in turn used to justify further colonization.

The basic infrastructural inequality that emerged across the Mandate persisted within the new State of Israel in 1948. Israel’s gradual extension of the grid across newly acquired territories fostered Palestinian dependence on Israeli power.

Palestinians lagged behind in electricity access while new Jewish settlements were connected to the grid from their inception. The successor to the PEC, the Israel Electric Company (IEC), held the monopoly on power generation within Israel, making it impossible for Palestinians to establish independent grids. In Gaza, the Egyptian authorities allowed municipalities to purchase generators and provide electricity to their populations. In the West Bank, annexed to Jordan, nearly a dozen power companies were established. The largest was the privately owned Jerusalem District Electricity Company (JDECO), based on the city’s Ottoman-era concession, which served Jerusalem, Ramallah, Bethlehem and neighboring towns and villages. The rest of the West Bank was served by village-level cooperatives or municipal companies in cities like Nablus, Jenin and Hebron.

Following Israel’s conquest of the West Bank, Gaza, Sinai and Golan Heights in the 1967 War, the Israeli state, the Jewish Agency and international development organizations, like USAID, invested heavily in infrastructure for new settlements. Palestinian villages that desired access to the IEC or West Bank grids, on the other hand, often had to raise the requisite capital themselves.

By the mid-1970s, around a quarter of Palestinians living in Israel’s pre-1967 borders, two-thirds of Palestinians in the West Bank and three-quarters of Palestinians in Gaza still lacked power.

The period after 1967 saw an increase in overall electricity consumption by Palestinians living in historic Palestine. But profound inequality persisted. By the mid-1970s, around a quarter of Palestinians living in Israel’s pre-1967 borders, two-thirds of Palestinians in the West Bank and three-quarters of Palestinians in Gaza still lacked power.[3]

Moreover, electricity came at a price. As Laleh Khalili has observed, “after 1967, the occupied territories were made deliberately reliant on Israeli infrastructures that could be switched off at a flick of a switch…”[4] In November of that year, Israel implemented Military Order 159, placing electricity infrastructure in the occupied territories under Israeli control. Israel required Palestinian power companies to sell their electricity at low rates fixed by the government. Unlike the IEC, these companies lacked the state subsidies and economies of scale to sell electricity at fixed prices profitably. Moreover, Israeli occupation authorities frequently prevented Palestinian companies from expanding their facilities. For example, military orders barred Palestinians from assembling new electrical infrastructure without IDF approval. In most cases, approval was not forthcoming unless it connected to the IEC grid. Such policies rendered Palestinian power companies unprofitable and prevented new investment, facilitating the IEC’s takeover of electricity provision throughout the West Bank.

In Gaza, electrification sustained the post-1967 occupation in multiple ways. The Israeli state required the IEC to serve new Jewish settlements and bases in the enclave, paving the way for the company to begin selling power to its Palestinian municipalities. New electricity infrastructure powered military facilities, lit streets to increase visibility (and surveillance) and locked in a pattern of limited and dependent development.

By the late 1970s, only a few larger Palestinian cities like Jerusalem, Nablus and Jenin remained in control of their own power supplies. The Israeli government required that JDECO serve new settlements and IDF military facilities in the West Bank alongside growing numbers of Palestinians—part of a broader deal that granted the company new customers but required it lower its prices to Israeli standards. Moreover, the company was denied permission to sufficiently expand its generating capacity, forcing it to purchase most of its electricity from the IEC for resale at fixed low rates. This arrangement eliminated JDECO’s profits, disrupted service by impeding essential maintenance and repairs and burdened it with debt to the IEC. The company was pushed toward bankruptcy and forced to subsist on loans from Arab states.

In the early 1980s, when Israel’s Likud-run government attempted (unsuccessfully) to take over JDECO on behalf of the IEC, it spurred a wave of protests and strikes. JDECO ultimately won an Israeli Supreme Court case rejecting the IEC’s claim. But by 1986, the company only generated around 3 percent of its electricity, buying the remainder from the IEC—a massive drop-off from 60 percent a decade earlier. [5] In the same year, the IEC absorbed Nablus and Jenin’s municipal systems and took over JDECO’s service provision to IDF bases and Jewish neighborhoods and settlements. These acts further eroded the company’s revenues and deepened Israeli control over East Jerusalem—contributing to the outbreak of the First Intifada.

In a 1983 interview, Palestinian lawyer and activist Jonathan Kuttab noted that “water and electricity are regularly cut off as a form of punishment” in the West Bank.[6] When the Palestine Liberation Organization declared the establishment of a Palestinian state in 1988, Israeli authorities retaliated by imposing a curfew and cutting off electricity throughout the occupied territories overnight. Throughout the First Intifada, Israeli commanders halted the supply of electricity and fuel to Palestinian communities for hours or days at a time.

Fostering Palestinian energy dependence enabled Israeli authorities to deny energy access as a core counterinsurgency tactic.

Palestinians responded to energy poverty and dependence in a variety of ways. Some secured their own energy supply at a very local level. Palestinians in Gaza, for instance, adopted solar power in the 1970s. Others used more confrontational and militant tactics. In 1969, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine destroyed power lines linking new settlements in the Naqab/Negev to a generating plant in Ashdod, recalling earlier disruptive actions during the nakba. During the First Intifada, Palestinians refused to pay electricity bills and sabotaged IEC infrastructure. Palestinians correctly perceived these long-running battles over energy as a critical component of the overall struggle for sovereignty.

Despite rhetoric at the time about Palestinian energy independence and cooperation between energy sectors, the Oslo process worked to consolidate and deepen Palestinian energy dependence on Israel.

Annex III of the 1993 Oslo Accords provided for “Cooperation in the field[s] of electricity… [and] energy,” including “joint exploitation of… energy resources.”[7] But as Lior Herman and Itay Fischhendler have noted, during the Oslo process “Israel saw electricity as a future foreign policy instrument and wanted to control the production and transmission processes in order to preserve Palestinian dependence on Israel, even after its independence.”[8] Though they overstate Israel’s willingness to accept eventual Palestinian sovereignty—and are therefore incorrect in describing this as a matter of foreign policy rather than an aspect of continued occupation—Herman and Fischhendler nonetheless correctly identify how Oslo-era infrastructural and institutional arrangements were designed to maintain and intensify Palestinian subordination.

The Oslo process created multiple chokepoints that gave Israel control over Palestinian energy, financial and other critical flows. Under Oslo, the IEC remained responsible for most electricity production and transmission throughout Gaza and the West Bank. Fearing the IEC would be unable to collect on Palestinian electricity debt, Israeli negotiators created a mechanism to withhold Palestinian customs revenues and taxes on Palestinian migrant workers collected by Israel. Municipalities were frequently unable to repay the IEC for the power they purchased, accumulating significant debt for which the new Palestinian Authority (PA) was ultimately responsible. The PA has attempted to use prepaid electricity meters to pass this debt on to Palestinian consumers, especially in refugee camps where consumers frequently refuse to pay for electricity.

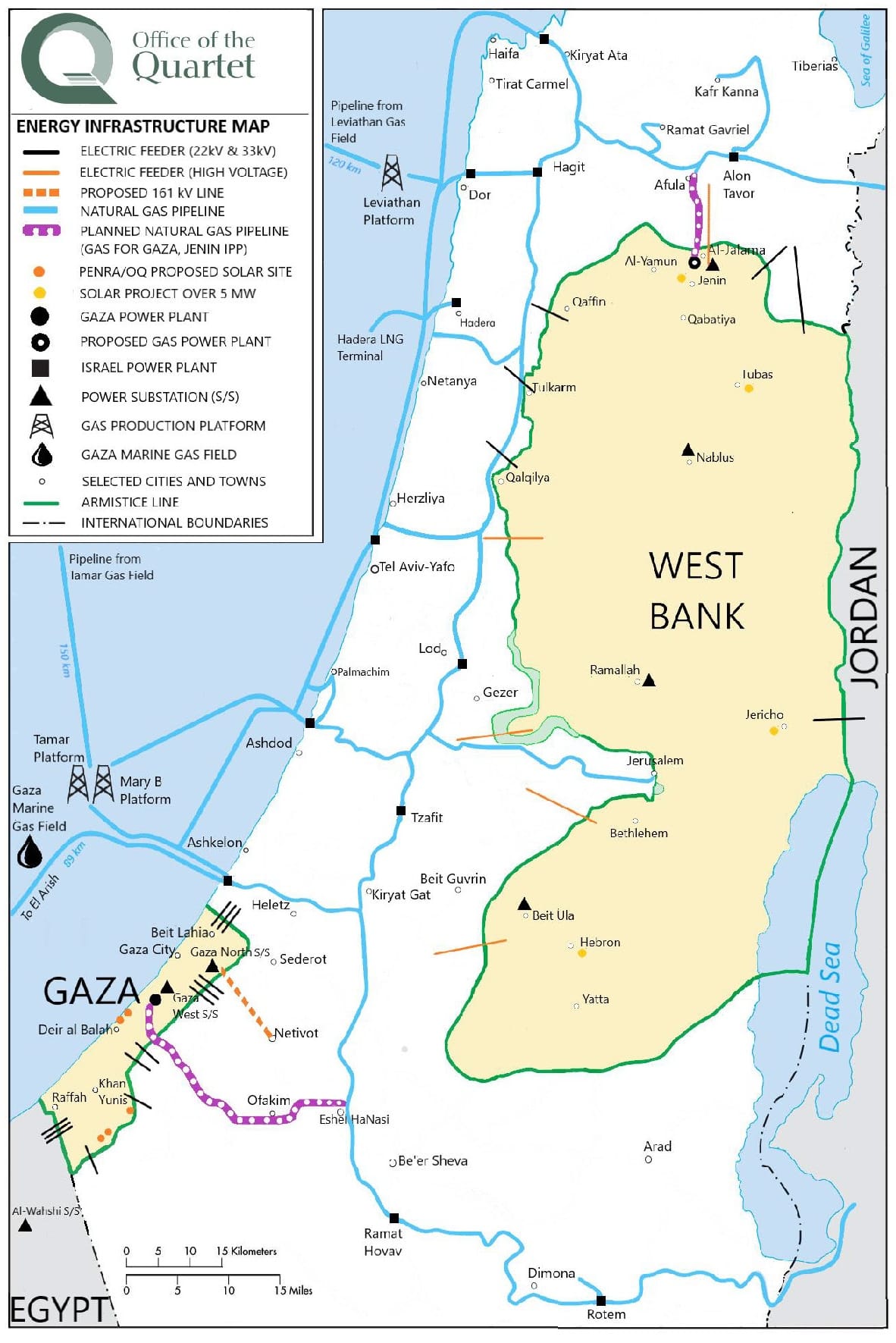

The PA made some efforts to secure a limited degree of energy independence in the Oslo era. Planning for a power plant in Gaza, for instance, began in 1994. Gaza’s power plant—completed in 2002 and powered by expensive imported Israeli diesel—provided around two-thirds of the strip’s electricity.[9] But as Adam Hanieh notes, the 1994 Paris Protocol, which regulated the PA’s relationship with Israel, put Israel in “complete control over all external borders.”[10] Israel controlled the importation of fuel destined for Gaza’s power plant and the rest of the occupied territories. According to the World Bank, the terminals where the West Bank and Gaza received fuel lacked storage facilities, rendering “Palestinians dependent on a day-to-day supply from Israeli companies” and therefore extremely vulnerable to fuel cutoffs.[11]

In 1999, natural gas was discovered off Gaza’s coast. This field, called Gaza Marine, might have provided inexpensive electricity from a Palestinian-controlled fuel source. But while Israeli authorities entertained the possibility of allowing British Gas to develop Gaza Marine—and even of purchasing natural gas from this Palestinian-controlled field—Israel ultimately never permitted this resource to be developed.

Instead, the post-Oslo period consolidated deep energy dependence on Israel that aligned with a broader strategy of fostering overall Palestinian economic dependence while circumscribing Palestinian sovereignty.

Instead, the post-Oslo period consolidated deep energy dependence on Israel that aligned with a broader strategy of fostering overall Palestinian economic dependence while circumscribing Palestinian sovereignty. By the year 2000, more than 99 percent of Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza had access to fundamentally Israeli-controlled electricity, and Israel continued to weaponize this dependence.[12]

Throughout the Second Intifada, Israel routinely stopped the entry of fuel into Gaza for use by its power plant. Israeli forces also directly targeted Palestinian energy infrastructures. During raids, Israeli forces regularly shot out streetlights and cut off electricity to Palestinian neighborhoods so they could operate under cover of darkness. Attacks on medical facilities damaged generators, disrupting medical care. According to a 2002 World Bank report, in Hebron “Electricity transformers [were] shot out, in large numbers and repeatedly, causing frequent disruptions...”[13] The Palestinian Energy Authority estimated that Israeli forces were directly responsible for the destruction of $15 million worth of power infrastructure between 2000 and 2003, though this figure likely understates the true toll of such tactics, given energy’s centrality to economic life.[14]

Since Oslo and the 2005 evacuation of Gaza, control over energy and other critical infrastructures, alongside the use of airpower, has allowed Israel to engage in what Salamanca has called a “remote control” occupation.[15]

After Hamas’ victory in Palestinian parliamentary elections, its seizure of control in Gaza and the capture of IDF soldier Gilad Shalit in 2006, Israeli forces bombed Gaza’s power plant, thereby impeding medical care throughout the territory. The plant was repaired in 2007, but Israeli authorities declared Gaza a “hostile territory” and began employing the restriction of fuel supplies into Gaza as a siege tactic, providing only enough fuel, electricity, water, food and other essential goods to meet a purported humanitarian minimum.[16]

During fighting between Israel and Hamas in 2008, Israel cut off Gaza’s fuel supply entirely, damaged power lines extending into Gaza from both Israel and Egypt and restricted the entry of spare parts required to maintain and repair the power plant. The plant’s fuel storage tanks were targeted again in the 2014 assault on Gaza. In 2021’s brief war, Israeli authorities restricted the supply of electricity from the IEC to Gaza, and the IDF bombed a recently constructed solar facility. Israel again reduced the flow of fuel into Gaza in late 2021 and 2022, restricting the power plant’s ability to generate electricity.

The West Bank’s energy supply, while subjected to fewer sieges and bombardments than Gaza’s, has also been targeted by Israeli authorities. For example, the IEC cut power to Nablus and Jenin when these municipalities failed to pay their power bills after Israel withheld tax revenues from the PA in retaliation for Palestine’s accession to the International Criminal Court in 2015.

Before October 7, 2023, Gaza spent more than a fifth of its GDP on energy imported directly from Israel and received an average of only 10 hours of electricity per day.

Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza have responded creatively. Some established informal connections to the grid in the West Bank, expropriating electricity from the IEC while adding to the PA’s debt burden. Small diesel generators have insulated those who can afford them from power disruptions. Outside of the reach of Israeli authorities, who frequently confiscate or destroy solar panels in the West Bank, Palestinians in Gaza widely adopted solar power from the 2010s onward, with solar panel coverage growing from 115 to 20,000 square meters between 2012 and 2019 and solar energy providing as much as 12 percent of the strip’s power supply.[17]

But despite these local solutions, Palestinians consume the least energy per capita in the Middle East, while paying the highest price for it. As with so many other aspects of Palestinian life, energy poverty is the result of a fundamentally extractive relationship: Before October 7, 2023, Gaza spent more than a fifth of its GDP on energy imported directly from Israel and received an average of only 10 hours of electricity per day.

Whereas Israeli authorities carefully modulated the denial of energy in their post-1967 and post-Oslo counterinsurgency campaigns, the eliminationist war that followed October 7, 2023 witnessed the near-absolute blockade of Gaza’s energy supply and wholesale targeting of energy infrastructure. Israeli authorities cut off the flow of electricity and fuel almost entirely, only intermittently allowing miniscule amounts of fuel to trickle in under international pressure.

Israeli forces have also damaged equipment ranging from cranes used by the Gaza Electricity Distribution Company to the high voltage electricity connection points that enable the import of Israeli electricity. By March 2024, the World Bank conservatively estimated that Israel had destroyed more than 60 percent of Gaza’s power distribution network.[18] Around the same time, Gaza’s energy authority estimated $500 million in damage to energy infrastructure and suggested that around 90 percent of the strip’s solar panels had been damaged.[19] Amnesty International asserts that 11 of Gaza’s 17 largest solar plants have been damaged or destroyed, and Human Rights Watch has documented the intentional bulldozing of solar panels powering wastewater treatment plants.

The impact of the rapid, near-total disruption to Gaza’s energy supply has been catastrophic. Hospitals—which have themselves been routine IDF targets—have struggled to secure fuel for their generators in the absence of electricity. As a result, the dwindling number of functioning medical facilities have been forced to provide care for the tens of thousands of wounded civilians without power.

Still, Palestinians have found innovative workarounds to these dire conditions, establishing communal charging stations using the few remaining solar panels and even improvising small-scale wind turbines mounted on tents and rooftops.

In February 2024, satellite imagery analysis by Care International revealed that 70 percent of Gaza’s hospitals lacked lighting at night, even as they operated at more than three times their capacity. The lack of energy has exacerbated famine conditions and inhibited already intentionally constrained relief efforts. Without power, for example, Palestinians in Gaza struggle to turn flour delivered as humanitarian aid into edible bread. The lack of fuel and electricity has also halted the work of desalination plants, reducing the availability of water to less than a third of the amount required per capita. It has likewise disrupted the sanitation system and thus contributed to the outbreak of polio. It has disrupted telecommunications, denying Palestinians in Gaza access to the macabre maps meant to direct them to so-called safe zones and—together with the repeated, intentional killing of journalists—cutting off links to the outside world. Still, Palestinians have found innovative workarounds to these dire conditions, establishing communal charging stations using the few remaining solar panels and even improvising small-scale wind turbines mounted on tents and rooftops.

In the West Bank, since October 7, 2023, the Israeli government has used electricity debt as a pretext to withhold large amounts of tax revenue from the PA. The maintenance of Palestinian electricity dependence, and the set of institutional arrangements developed under Oslo that put Palestinian fiscal channels under Israeli control, has created a mechanism for collective punishment and a means by which Israel has brought the PA to the brink of collapse amid an apparent push to annex the West Bank.

Finally, Israel has used the opening created by this war to expropriate Palestinian energy resources. In 2019, the State of Palestine formally declared its maritime boundaries in accordance with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, claiming maritime areas off the Gazan coast. Israel has disputed these boundaries on the basis of its non-recognition of Palestine as a sovereign state. On October 29, 2023, Israel’s Ministry of Energy awarded licenses for Israeli and international energy companies to explore for natural gas in a zone off Gaza that overlaps substantially with the maritime area claimed by Palestine. This move undermines the basis for future Palestinian energy sovereignty and parallels the accelerated colonization of the West Bank.

Across this genocidal war, US and European leaders have consistently promised Palestinians a path to statehood following the conclusion of a cease-fire agreement. But as Rashid Khalidi has argued, the two-state formula is an illusion: “Palestinian statehood and sovereignty… have never been on the table, ever, anywhere, at any stage, from any party, the United States or Israel or anybody else.”[20] The long-term fostering and exploitation of Palestinian energy dependence underlines this point.

Any meaningful end to the occupation and colonization of Palestine must include Palestinian control over energy supplies, whether in the form of a centralized, fossil-fueled grid based around the development of Palestine’s offshore natural gas resources or a more durable and decentralized grid based around locally controlled solar energy. It must be up to Palestinians to determine what substantive energy sovereignty—and a livable future—will look like.

Read theprevious article.

Read thenext article.

This article appears in MER issue 313 “Resistance—The Axis and Beyond.”

[Zachary Davis Cuyler is an assistant professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago and a fellow with Century International.]

[1] Omar Jabary Salamanca, “Unplug and Play: Manufacturing Collapse in Gaza,” Human Geography 4/1 (March 2011).

[2] Fredrik Meiton, Electrical Palestine: Capital and Technology from Empire to Nation (University of California Press, 2019), pp. 56–7, 74–5, 80–94, 153–155, 164–166, 182–187.

[3] Sabri Jiryis, “The Arabs in Israel, 1973-79,” Journal of Palestine Studies 8/4 (1979), p. 54. Jamil Hilal, "Class Transformation in the West Bank and Gaza," Journal of Palestine Studies 6/2 (1977), p. 170.

[4] Laleh Khalili, “As They Laid Down Their Cables,” Granta, April 25, 2024.

[5] Jawdat Abu ‘Awn, “Electrical Energy in the West Bank and Gaza,” Samid al-Iqtisadi 15/92 (April-June 1993), p. 20.

[6] Jonathan Kuttab and John Egan, “An Autonomous Palestinian Presence on the West Bank Conflicts with the Goal of Judaization,” Journal of Palestine Studies 12/ 4 (1983), pp. 64–70.

[7] “Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements (Oslo Accords),” United Nations: Peacemaker.

[8] Lior Herman and Itay Fischhendler, “Energy as a Rewarding and Punitive Foreign Policy Instrument: The Case of Israeli–Palestinian Relations,” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 44/6 (2021), p. 505.

[9] World Bank, Report No. 39695-GZ: “West Bank and Gaza Energy Sector Review,” May 2007, p. 3.

[10] Adam Hanieh, “The Oslo Illusion,” Jacobin, April 2013.

[11] World Bank, Report No. 39695-GZ: “West Bank and Gaza Energy Sector Review,” May 2007, p. 12.

[12] Ayman Abualkhair, "Electricity sector in the Palestinian territories: Which priorities for development and peace?,” Energy Policy 35/4 (2007), p. 2209–2230.

[13] World Bank, “Fifteen Months—Intifada, Closures, and Palestinian Economic Crisis: An Assessment,” 2002, 56–7.

[14] Ayman Abualkhair, "Electricity sector in the Palestinian territories: Which priorities for development and peace?,” Energy Policy 35/4 (2007), p. 2209–2230.

[15] Omar Jabary Salamanca, “Unplug and Play: Manufacturing Collapse in Gaza,” Human Geography 4/1 (2011), p. 25.

[16] Ibid, p. 29.

[17] Asmaa Abu Mezeid, “Confronting Energy Poverty in Gaza,” Al-Shabaka, March 29, 2023.

[18] World Bank, “Gaza Interim Damage Assessment,” March 29, 2024, p. 10.

[19] “Gaza energy sector losses exceed $500 million,” Attaqa, April 11, 2024. [Arabic]

[20] Rashid Khalidi, “The Neck and the Sword,” New Left Review 147 (May/June 2024).