Israel’s current war on Gaza, waged in the wake of Hamas’ October 7 attack, has been the most violent and destructive in its history of campaigns there.

Palestinians conduct a search and rescue operation after the second bombardment of the Israeli army in 24 hours at Jabalya refugee camp in Gaza, on November 1, 2023. Fadi Alwhidi/Anadolu via Getty Images

In less than one month, Israel has dropped more than 25,000 tons of explosives on Gaza, demolishing the urban landscape and killing over 10,000 Palestinians. Given the sheer scale of violence and its leveling of homes, hospitals, schools and the civilians in them, the laws of war (also known as International Humanitarian Law, IHL) have become a renewed source of debate and scrutiny—most recently following the bombing of the Jabalia refugee camp on October 31, in which Israeli airstrikes killed at least 50 people in an attack that was allegedly targeting a single Hamas commander.

Writing in these pages in 2016, Lisa Hajjar noted Israel’s role as innovator when it comes to pushing the limits of international humanitarian law and challenging the law’s protections of civilians (the article, from MER issue 279, is worth reading in full). At the time, Hajjar speculated that Israel’s new interpretations might alter legal norms, mainstreaming extreme state violence. The piece is important for moving beyond the question of whether violence is legal to underscore the unevenness of humanitarian law as powerful states maneuver within it. To discuss these and other facets of the law as it is being mobilized in Israel’s ongoing campaign on Gaza, MERIP’s managing editor, Marya Hannun, spoke to Neve Gordon, professor of international law and human rights at Queen Mary University in London and co-author (with Nicola Perugini) of Human Shields: A History of People in the Line of Fire (University of California Press, 2020). Their conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Marya Hannun: Before we get into the context of the October 7 Hamas attacks on Israel and the Israeli-declared war on Gaza that has followed, could you begin by talking about the basic differences between human rights law and the laws of war?

Neve Gordon: There are two bodies of law that in the popular conception are often conflated, but they are very different. One is human rights law. The other is humanitarian law—also known as laws of armed conflict or laws of war—which are all the same and refer to another body of law. Contrary to human rights law, which recognizes the right to life as a basic right, the laws of war allow killing of military targets.

The bedrock of international humanitarian law, or the laws of war, is the principle of distinction. This principle calls on warring parties to distinguish between civilians and combatants: It permits the targeting of combatants and military sites, and it protects civilians and civilian sites.

But in addition to a legal fiat regulating what is allowed and what is prohibited, one thing that I and many others before me have shown is how the laws of war produce a civilizational divide between those who ostensibly make distinctions and are cast as “civilized” and those who do not. If an individual or group does not recognize or abide by the principle of distinction then that person or group is cast as uncivilized or barbaric. In this way, the laws of war participate in a dehumanizing process of warring parties. Historically, those accused of barbarism have often been non-state actors. This divide often works according to the color line.

Marya: We’ve certainly seen that mobilized recently by the US administration under President Biden in his support of Israel’s ongoing bombing campaign—an us vs. them divide. On October 10, already three days into the campaign that had cut off fuel and electricity, and as Israel was actively killing civilians, the president remarked that unlike Hamas, “we [Israel and the United States] uphold the laws of war… It matters.”[1]

Marya: Regarding the attacks by Hamas on Israeli military and civilian sites and the taking of more than 200 hostages and the relentless bombing campaign on Gaza, in which hospitals, schools and ambulances have been targeted, how are you seeing the laws of war being applied?

Neve: It is obvious to anyone who studies the laws of war that Hamas violated the principle of distinction on October 7 by targeting civilian populations through the use of heinous violence. These are clearly war crimes, and those responsible should be held accountable. It is also obvious that Israel has committed war crimes in Gaza since October 7: There is the collective punishment through the stopping of water and electricity, the compelled movement of populations and then the unleashing of eruptive violence that is killing thousands of civilians while destroying the very infrastructure of existence in the Gaza Strip.

But I think we can identify a change in how the Hebrew press has discussed the question of the laws of war since October 7, 2023. This is the fifth round of intense bombing on Gaza since 2008, and in all of the previous rounds, it was very important for Israel to carry out legal acrobatics to prove that it was not committing war crimes—that it was abiding by the laws of war. Whether the international community and legal scholars abroad agreed or not is a different question. For example, in 2012 and 2014, as the fighting was still going on, Israel’s spokespeople used various legal arguments to justify bombing hospitals and killing civilians. While that is certainly happening now too, a different kind of refrain is voiced on Israeli TV and the Hebrew press. I’m seeing a regular claim that the law and the Supreme Court have been limiting and have not allowed Israel to go far enough, and that this time, we’re not going to let the law hold us back. In English, I haven’t seen this disregard for the law by Israel’s official commentators, but in Hebrew commentator after commentator is saying this. That is a difference.

Marya: Is this shift that you’re describing related to the recent judicial overhaul in Israel, in which Netanyahu’s government has been trying to push through legislation limiting the Supreme Court’s oversight?

Neve: Absolutely. The refrain that this has to be a war without the Supreme Court very clearly feeds into the desires of those pushing the judicial overhaul. Israel’s far right sees liberal law as a threat to what they want to accomplish. As an aside, it might be worth saying that the ultimate objective of Netanyahu’s government is to change the meaning of democracy. The judicial overhaul is part of an effort to undo the link between democracy and liberalism and to introduce the notion of apartheid democracy—namely, that a democracy can also be an apartheid regime.

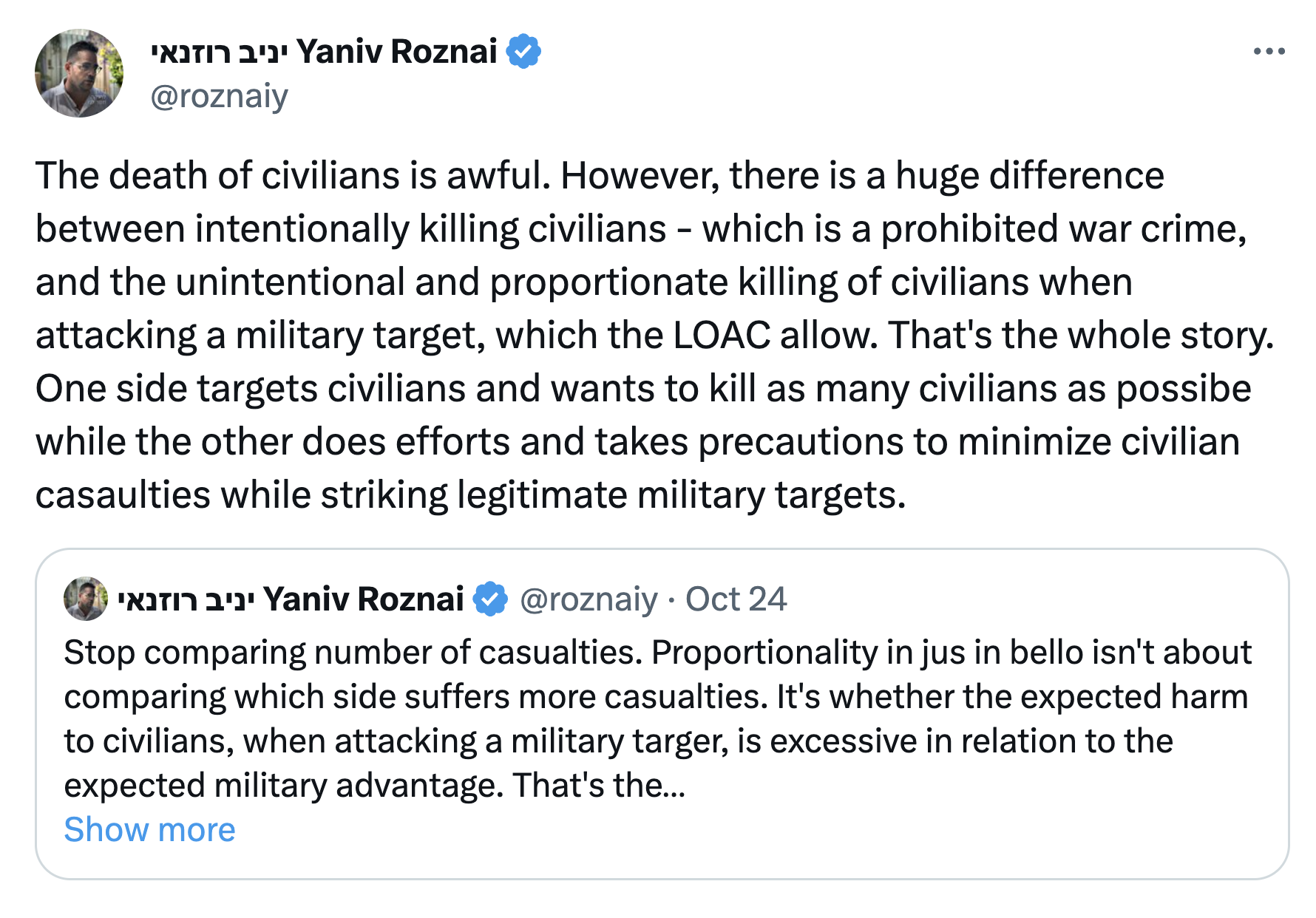

Marya: But as you noted, there are still efforts to convince the international community that Israel is upholding the laws of war, and in English we’re seeing a lot of this discourse around questions of intentionality and proportionality. You’ve quoted a tweet by Israeli jurist Yaniv Roznai, published on October 24 telling readers to stop comparing the casualties between Israelis and Palestinians: “The death of civilians is awful. However, there is a huge difference between intentionally killing civilians—which is a prohibited war crime, and the unintentional and proportionate killing of civilians when attacking a military target, which the LOAC [Laws of Armed Conflict] allow. That’s the whole story. One side targets civilians and wants to kill as many civilians as possibe [sic] while the other does efforts and takes precautions to minimize civilian casaulties [sic] while striking legitimate military targets.”[2]

Screen shot of the Tweet by Yaniv Roznai from October 24, 2023.

Neve: Let’s untangle this a bit. There are two legal ideas that are used here to suggest that even though Israel has killed many more civilians than Hamas did, it did not necessarily commit war crimes. Let’s begin by looking at intentionality. About a month ago, the American CBS news program 60 Minutes interviewed Shira Etting, an Israeli pilot who had been active in the protests against Netanyahu’s government.

“If you want pilots to be able to fly and shoot bombs and missiles into houses knowing they might be killing children,” she said, “they must have the strongest confidence in the [politicians] making those decisions.”[3] Etting nowhere admits to any intention of killing children. Yet she does acknowledge that when she and her fellow pilots set off on a mission over Gaza, they understand that the missiles they fire may very well—and often do—end up killing noncombatants.

Intention and knowledge are different according to the laws of war, and therefore when pilots drop bombs, even if they know they are bombing one of the most densely populated places in the world and will kill many civilians by doing so, they have not necessarily carried out a war crime. In other words, if the pilots know they were killing civilians but did not intend to (whatever that might mean), other factors like the principles of proportionality and military necessity have to be weighed in order to determine if it was a war crime.

Marya: How does this relate to the principle of proportionality?

Neve: Many of these principles, and particularly the principle of proportionality, are very ambiguous, which leaves much room for interpretation. On the face of it, the principle is simple. It says that when one attacks a legitimate military target, the expected military advantage must outweigh the anticipated harm to civilians. There’s a lot of things going on here.

Simultaneously, we see here the mobilization of a civilizational discourse which characterizes the civilians who are killed and the civilian sites that are destroyed as “collateral damage.” It’s a term I would not use, ever, except in quotation marks. It is a term used to render all those that were killed as statistics, as numbers, as people who do not have parents, or children or a family that cares for them; they have no relationships, aspirations and dreams. This is part of the politics of grievability that distinguishes between people who are grievable and others who are not and ends up facilitating the deployment of violence.

Marya: Another IDF talking point repeated by US Secretary of State Antony Blinken and President Joe Biden in their support of Israeli aggression is that Hamas uses civilians as human shields. What legal work does this claim do?

Neve: Modern warfare in general but particularly in the context of Gaza is urban warfare. Gaza, as mentioned, is one of the most densely populated places in the world today, and half the population there are children. The laws of war were first developed when fighting typically occurred between two armies confronting each other in an open field. But what happens when the fighting is taking place in an urban context? And when one of the warring parties is a non-state actor in a situation of warfare that is so asymmetrical? This is a staggeringly asymmetric conflict: You have a nuclear power with access to the most advanced weapons in the world, the most advanced intelligence, and then you have the fighters who are using tunnels, machine guns, rockets and maybe some drones. The way they are going to hide is in city spaces since they have no chance to survive in open terrain. Now, the laws of war were not really created to deal with this kind of warfare. And yet, there’s the principle of distinction. If the principle of distinction applies, and you have to distinguish between combatants and civilians, then those who want to bomb a city in order to kill combatants have to justify doing so, and they can justify it in a number of ways.

One way is to frame thousands of civilians as human shields. When a person in a battlefield is defined as a human shield—a vulnerable civilian body that willingly or not becomes a tool of warfare whose function is to render a military target immune—he or she loses some of the protections assigned to civilians by the laws of war and an ethical quandary surfaces. What many legal commentators say is that once a warring party uses human shields, lethal forms of violence that might otherwise be prohibited in a civilian setting can be used. There are limitations about killing human shields relating to the principles of proportionality, precaution and military necessity, but in general, one can cast whole populations as human shields and this relaxes the limits on the repertoires of lethal violence that can be used.

This has been playing out in Gaza both in relation to large populations and to hospitals, schools, universities and other protected sites. For instance, on October 13, Israel instructed 1.1 million civilians to flee from the north to the south. Judging from the instructions soldiers received in 2014, Israel assumes that those who remain in the north are either civilians who are participating in hostilities and therefore can be killed according to the laws of war, or they are human shields, and therefore, the repertoires of violence can be relaxed and they too become killable subjects. What Israel can claim and will claim is that the deaths of all civilians killed in the north after it told them to leave are, legally speaking, the responsibility of Hamas because it used them as human shields.

Nicola Perugini and I have shown how hundreds of thousands of people have been framed as human shields in recent asymmetric wars between state and non-state actors in places like Mosul, Sri Lanka and Gaza. In these instances the human shield argument can be used to justify an elimination project. It’s not being used to justify the killing of 20 civilians but to legitimize a Nakba-esque logic. These are instances in which the laws of war are mobilized to facilitate the use of lethal violence against civilian populations.

Marya: Since October 7, there have been a number of attacks on healthcare facilities in Gaza. 23 hospitals have received evacuation orders. Israel has targeted medical facilities in the past, if not at this scale. How does the shield argument get deployed here?

Neve: Perugini and I have studied the “hospital shield” argument quite extensively in several contexts. It is still not entirely clear who is responsible for the bombing of Al Ahli hospital on October 17, but hospital and health care facilities have been systematically bombed since October 7 and the attacks have increased to an unprecedented level in this round of fighting. As of October 30, the World Health Organization documented 82 attacks against medical units in the Gaza Strip. The attacks have so far affected 36 health care facilities (including 21 hospitals damaged) and 28 ambulances. 71 percent (51 of 72) of primary care facilities no longer function, while 12 out of 35 hospitals are not functioning due to damage from the bombing and/or lack of fuel, electricity or basic medicines, and these numbers continue to rise.[4] This in itself has a clear eliminationist drive to it because hospitals are not only “protected sites,” they are a fundamental part of the infrastructure of existence, responsible for saving and sustaining the lives of Gaza’s inhabitants, including the sick and the wounded.

Marya: So to conclude, in light of this conversation, I am curious about your overall assessment of humanitarian law. Who do the laws of war ultimately benefit? Can they be an effective tool to protect people?

Neve: Can we trust the laws of war to protect people from state violence? I don’t think we can. First, we need to keep in mind that the law knows no history and focuses solely on regulating the fighting. The context in which a war is taking place and particularly the asymmetry of power do not really matter. This narrow framing already puts the weak at a disadvantage when using the laws of war. Second, the laws of war have little if anything to say about structural violence and only deal with eruptive violence—violence that is agent-driven and deployed for a certain period of time before it recedes. We need to keep in mind that it could be the case that more people will die in Gaza in the aftermath of the war due to structural violence than those who have been and will be killed due to eruptive violence. The laws of war have nothing to say about that.

Third, it’s important to remember that the laws of war were created by state parties and were drafted to regulate violence between states. As international legal scholar Antony Anghie has shown us, the laws of war were always implicated within the imperial and colonial project and helped advance this project. The colonized were never conceived as a state party. The law helped cast them as barbarians, and when they resisted the colonizer, the laws of war were deemed inapplicable and the colonizer did not have to abide by them when repressing resistance. Non-state actors have a clear disadvantage in the international arena; they did not participate in the drafting of the 1949 Geneva Conventions, and therefore their views and interests are not necessarily articulated in the Conventions. The 1977 Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions were drafted after decolonization and included several state parties that had formerly been colonized. They managed to introduce a single clause that allows non-state actors to use arms when resisting colonial domination, alien occupation or racist regimes. But in a war between a state party and a non-state actor, the laws of war definitely favor state parties. Non-state combatants tend to be considered unlawful combatants and therefore lose the protections and rights bestowed on state combatants. Moreover, the laws in general benefit the strong. You can see that in the international arena in many ways—for example, the production of landmines is banned because they’re indiscriminate. But landmines are also a cheap weapon. Nuclear weapons and large bombs that can kill 1,000 or several hundred civilians are not banned, even though they too are indiscriminate. The law also lags behind technological developments, so what we see now in war is how cutting-edge high-tech states can carry out large parts of their work remotely. They have surgical weapons, and they can always claim that they did not intend to kill. This muddies the issue of intentionality.

The law is the master’s tool, to use Audre Lorde’s framing, and you cannot use the master’s tools to destroy the master’s house. I therefore do not think they can be used as a tool of emancipation or liberation, but at the same time, war crimes and crimes against humanity still have cachet in public. The law matters in setting public opinion, which is what we’re seeing now: It is less about their impact in a court of law and more about their impact in the court of public opinion. And in the court of public opinion the role of the laws of war is to produce the ethics of violence. They are used to frame the fighting and expose either the morality or immorality of the violence. In certain instances, then, we can definitely use them strategically to criticize forms of eruptive violence, and we might be able to influence the opinions of those in power, but to rely on them within legal forums is probably misguided.

Endnotes

[1] “Remarks by President Biden on the Terrorist Attacks in Israel,” Whitehouse Website, October 10, 2023.

[2] Yaniv Roznai on X on October 24, 2023: https://x.com/roznaiy/status/1716862775832588474?s=20

[3] Philip Weiss, “’60 Minutes’ says Israeli pilots who kill Palestinian children are ‘moral’ defenders of ‘democracy,’” Mondoweiss, September 18, 2023.

[4] “Hostilities in the Gaza Strip and Israel | Flash Update #25,” OCHA Report, October 31, 2023.

[5] “Customary IHL-Rule 28. Medical Units,” International Committee of Red Cross.

[6] “Dispute over Gaza hospital strike: what we know,” AFP, October 20, 2023.