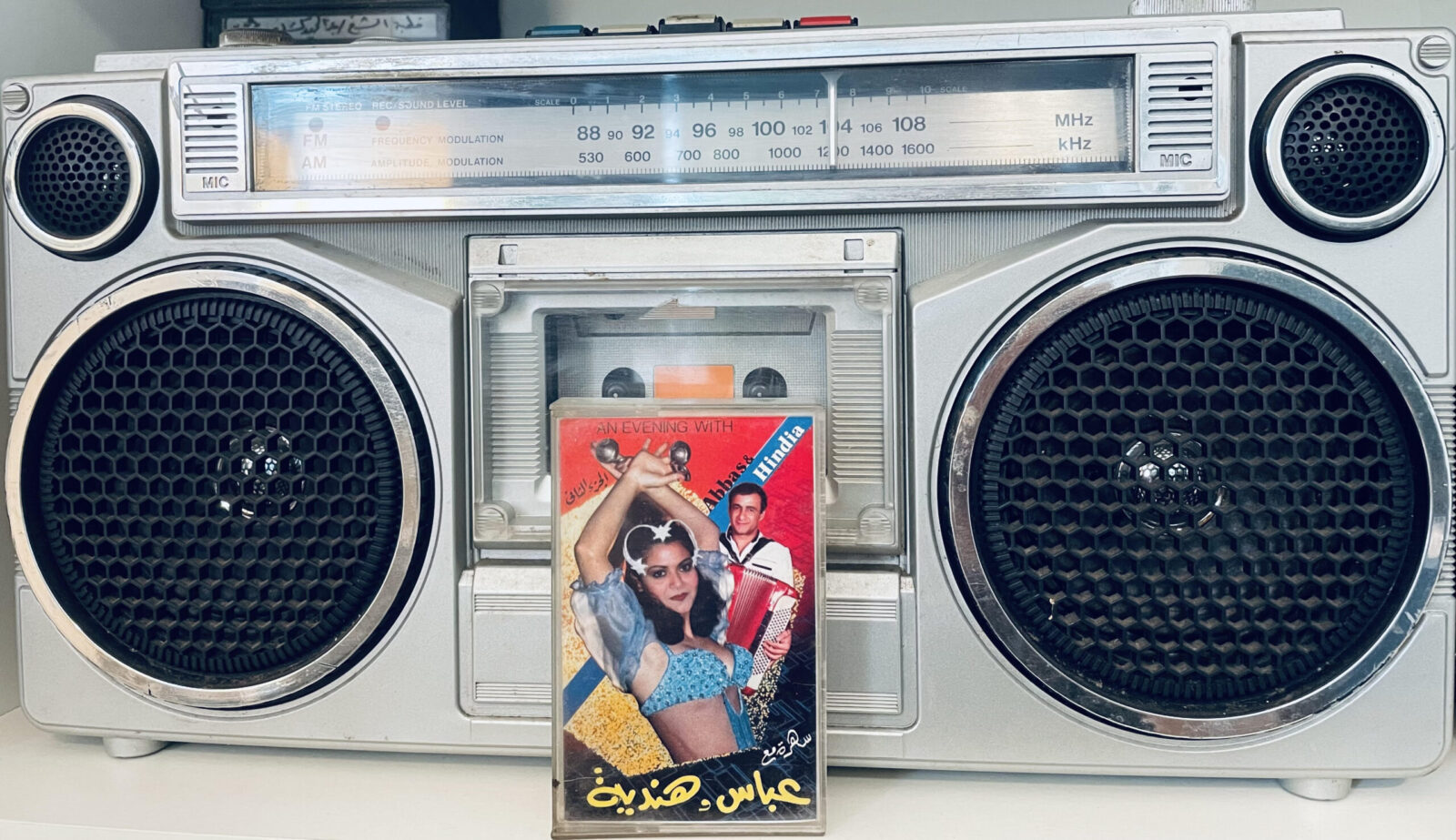

The cassette of An Evening with Abbas & Hindia Part 2. Photo by Andrew Simon.

After a stint in Saudi Arabia working in aluminum production, Mansur returned to Egypt in the 1980s with roughly 1,000 cassette tapes in tow. Not content with distribution alone, Mansur soon pivoted to A&R (Artists and repertoire), focusing on the search for and development of artistic talent. From Shubra, a northern Cairo neighborhood with a rich history of producing culture stretching back to the turn of the twentieth century, he launched the record label “Egyptphon.” The choice of name pointed to the fact that Mansur understood his endeavor in national terms. It also harkened back to an earlier era of the recording industry, when “phone” or “phon” (from phonograph) often served as a suffix for company names, such as Gramophone, Polyphon and Baidaphon.

Rather quickly, Mansur grasped what his largely working-class customers were after: the frenetic energy of wedding acts like “Abbas & Hindia.” The accordionist Abbas and the well-known belly dancer Hindia, who regularly graced Cairo’s hotel ballrooms, stood in stunning contrast to the staid balladeering of state-sanctioned musicians. Promoting the duo, in and of itself, was an act of subversion, one that Mansur carried out with ingenuity. To steer clear of the radio censor, Mansur avoided radio altogether, passing along Egyptphon releases free of charge to microbus drivers so that their sounds might be amplified for passengers-turned-prospective customers, without the required art license from the Ministry of Culture. Indeed, as long as the Egyptian state has sought to control cultural production, impresarios, artists and audiences have endeavored to challenge censorship in creative ways.

Andrew Simon’s Media of the Masses: Cassette Culture in Modern Egypt (Stanford University Press) offers both a history of “technology-in-use” and a musical biography. The book nimbly narrates Egyptian history in the last third of the twentieth century by zeroing in on the format used by Mansur and so many others during this period: the cassette. Making its debut in 1963, the compact cassette radically changed who and what could be heard, musically and otherwise, around the globe. With tapes, production was inexpensive, requiring little setup to record. The cost and size of the medium likewise made for easy distribution. Further, tapes were re-recordable, theoretically rendering them blank slates and, therefore, canvases. All of this meant that cassettes could conceal and be concealed, and a host of actors gained entry to an industry largely closed to them in the past. While the revolution may not have been televised, it was certainly carried on tape. Consider the rise of hip-hop, spread through the circulation of cassette tapes in the United States, in the mid- to late 1970s or the recorded sermons of Ayatollah Khomeini which fanned out across Iran. Simon’s book firmly adds Egypt to the historiographical mix.

Consuming Cassettes

Simon’s monograph is divided into an A side and a B side, although some of its most compelling material emanates from the flip.

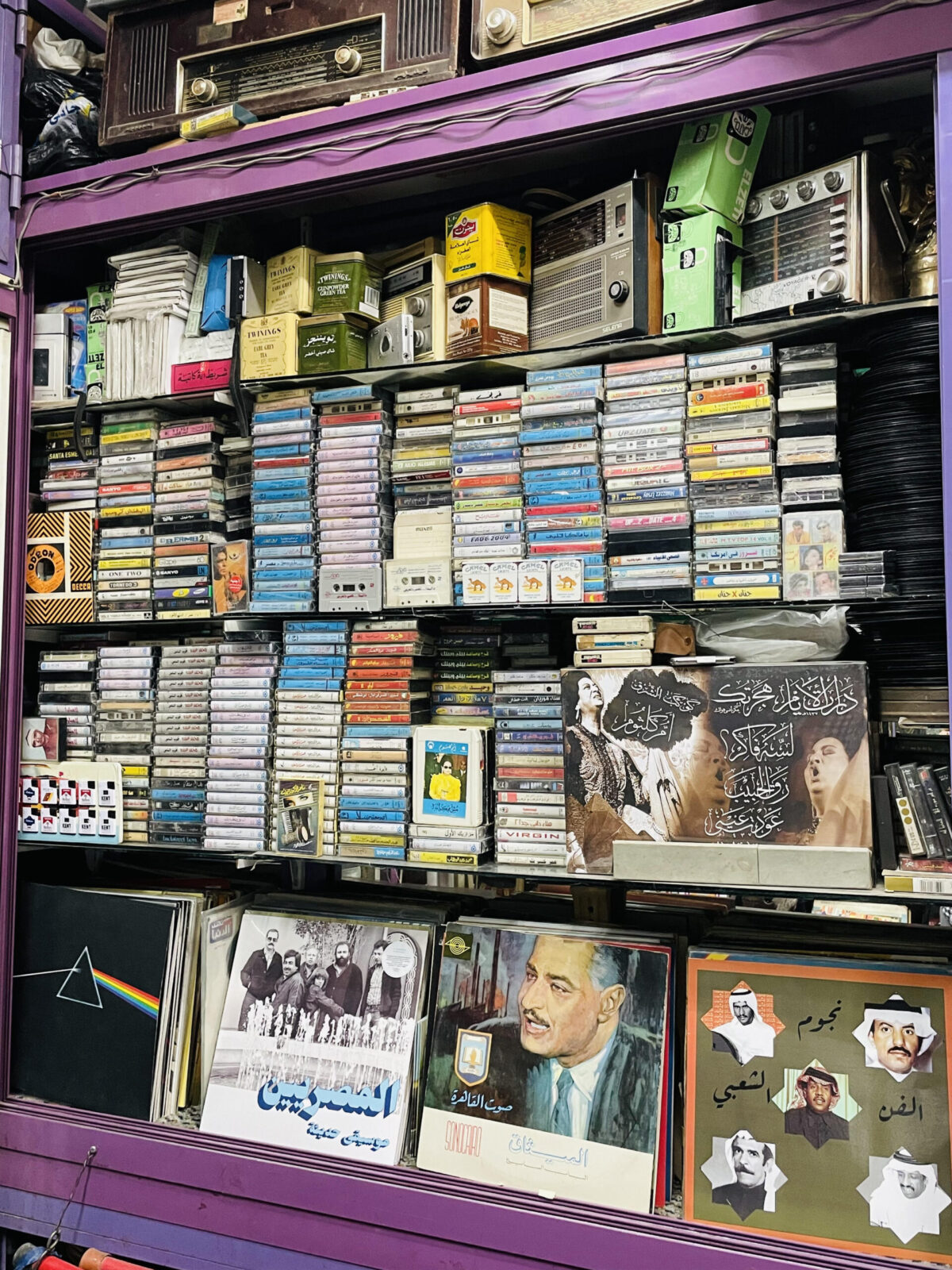

Inside the Cairo music shop Mazzika Zaman. Photo by Andrew Simon.

Chapter 1 outlines how cassettes first came to dominate the Egyptian media marketplace and the soundscape in the mid-1970s, a period when the country’s economy shifted aggressively toward capitalism and privatization under President Anwar Sadat’s infitah (“opening up”) policy. What Simon refers to as “cassette culture” was buoyed by a culture of consumption that first developed under Sadat and later ballooned under Husni Mubarak.

By the early 1980s, millions of kilograms of commercial goods were transiting through Cairo International Airport and other ports of entry––a sharp turn from the state of affairs under Egypt’s previous president, Gamal Abdel Nasser. Amid the refrigerators and washers and dryers were cassette players, which political elites eagerly adopted. They were also taken up by established musicians like ʿAbd al-Halim Hafiz, ʿAli Ismaʿil and Farid al-Atrash. Indeed, initially, cassette players were associated with these public figures rather than “the masses.” Images of cassette players displayed prominently in the salons and on the terraces of the well-heeled were broadcast to the public through state-controlled periodicals, helping to define the “modern” Egyptian home. As prices on the machines dropped, middle- and even working-class Egyptians found themselves able to obtain that ideal.

Of course, as the demand increased for cassette players, certain savvy individuals employed surreptitious means to supply them. In chapter 2, Simon pays careful attention to what he calls the “criminal biography” of the cassette player. Mining the censored Egyptian press for popular crime reports, he provides a sense of the sometimes boundless quality of the black market for commercial goods that grew during the infitah. Many engaged in theft and smuggling also maintained above board day jobs. Through their example, Simon captures the severity of the struggle of ordinary Egyptians attempting to navigate shortsighted economic policies. At the same time, that citizens were willing to risk run-ins with an authoritarian state to obtain machines for playing music reveals the high regard in which sound objects were initially held.

Recording and Circulation

Simon’s B side and chapter 3 deal more directly with the heart of Media of the Masses: Egypt’s recording industry of the 1970s and 1980s, the type of popular music (shaʿbi) that grew alongside it and the censorship apparatus erected by the state in response.

Over a 15-year period, cassette labels proliferated at a staggering pace. In 1975, around 20 outfits operated. By 1990, there were some 500 (86). One of the major beneficiaries was Ahmad ʿAdawiya, the then-30-something-year-old, who, among others, pioneered shaʿbi music. This expansive, often faster-paced genre drew on musical influences from around the globe as well as local rhythms. Themes of love (and sex) and class reigned supreme.

Though not conservatory trained, ʿAdawiya nonetheless had an enviable musical background and was gifted with a powerful voice. He learned his trade on Muhammad ʿAli Street—long an incubator for popular music—and through his connections to the vocalist Sharifa Fadil and lyricist Maʿmun al-Shinawi, also the artistic director for the major label Sawt al-hubb. In 1973, ʿAdawiya released his first major song, “al-Sah al-Dah Ambu,” which, as Walter Armbrust has written, “seem[ed] designed to do nothing more than urge young people to dance.”[1]

And dance young people did. An estimated 1 million copies were sold, provoking critics to slam ʿAdawiya and his popular cassette cohort as “vulgar.” With his emerging success, they decried, in Simon’s evocative turns of phrase, “the downfall of music, the end of high culture, and the death of taste” (80).

In several ill-fated attempts to reverse course, state-controlled Radio Cairo established multiple screening committees to prevent the likes and sounds of ʿAdawiya from ever appearing on air. The government set up an Office of Art Censorship to filter out “impurities” carried on tapes, and the state-operated label, Sawt al-Qahira, appealed to the Ministry of Culture to go against the offensive music—although to little effect.

The “re-recordability” of cassettes, as Simon elucidates in chapter 4 (“Copying”), posed a problem not only to the unadulterated spread of the “vulgar,” but equally to regimes of copyright. While “home taping” (recording from tape to tape or from radio to tape) was pervasive among ordinary Egyptians, the issue of infringement came to affect a number of more prominent figures. In a court case surfaced by Simon, legendary establishment artists ʿAbd al-Halim Hafiz and Muhammad ʿAbd al-Wahhab engaged in a protracted legal battle with Sayyid Ismaʿil, another legendary establishment artist, over the unauthorized reproduction of their music on his Randa Phone label. Egyptian authorities, sometimes encouraged by musicians themselves, proposed more forceful measures, including creating a cassette police unit and new laws to mete out fines and prison time. As for the stakes of “copying sounds,” Simon argues that, “this mundane activity, at a more fundamental level, radically altered the very movement of cultural material by empowering anyone with a tape recorder to become a cultural distributor at a time when recording labels reigned, mass media was state-controlled, and elite artists enjoyed great power in Egypt” (20).

Chapter 5 places the elusive protest singer and composer Shaykh Imam (1918–1995) at center stage to decenter journalistic accounts of Richard Nixon’s official visit to Cairo in 1974. His iconic and searing song, “Nixon Baba” (Father Nixon), made clear that not all Egyptians greeted the arrival of the fledgling US politician with the fanfare and excitement depicted in the press. This chapter demonstrates how a single recording can help to surface an untapped fount of archival material. Chapter 6 is a broader consideration of the “material traces of tapes past.” Here, Simon brings what he calls the “shadow archive” out of the shadows. To do so, he consults the often unsung historical actors who, against all odds, preserved the sounds of Egypt’s recent past. Among them is the enterprising Mansur ʿAbd al-ʿAl Mansur (of Egyptphon fame) and other intrepid archivists in all but name.

Along the way, Simon raises questions about cassette archives that once existed, about the provenance of collections that are still accessible, about approaches to cataloging, about informal assemblages on rotating shelves in kiosks––and sadly, about disappearing ones.

Listening to the Past

Simon’s Media of the Masses is a valuable and engaging addition to a growing literature demanding that readers listen for and to Egypt’s past to better understand the diverse array of actors who inhabited and shaped it. Given that rich historiographical sounding board, the book would have benefitted from more direct engagement with a range of scholars who have studied musical media in Egypt: from A.J. Racy on the origins of the Egyptian recording industry to Charles Hirschkind on Islamic revival carried on cassettes.

Cover of Media of the Masses by Andrew Simon.

Simon, at times, seems primarily concerned with providing a history of media decentralization that predates and therefore provincalizes the rise of satellite channels like Al Jazeera and the internet. But what about the music and technology that preceded and often ran in parallel to cassettes? Earlier twentieth-century media forms, like records, were also sold, desired, censored and even copied. They, too, served to subvert. Older but still new styles of popular music, especially the interwar offerings by female artists, were also decried as vulgar. Cassettes undoubtedly made a unique contribution to Egyptian society and sound, but the format is part of a longer historical trajectory.

What made tapes stand out in Egypt, as Simon asserts, was their scale, which was indebted to both widespread sharing among peers and piracy. Yet, vastness did not necessarily “democratize sound” (11), nor did it permit “anyone with a tape recorder” to become a “cultural producer” or “cultural distributor” (20). Almost all the figures explored in the book were men with connections to the establishment or the industry. Even Shaykh Imam, for example, released multiple LPs on commercial labels. The cassette may have made his music far more accessible, but one is left wondering how the technology preserved or propagated regional traditions, female repertoires or zar—the musical healing complex that Shaykh Imam saw fit to condemn in “Nixon Baba.” As for Mansur ʿAbd al-ʿAl Mansur, while his brief biography offers a glimpse of what a music industry in transition afforded outsiders, it is clear that he was far from just “anyone.” Mansur was a visionary with an ear for good music who, thanks to his acumen, now had a chance.

One cannot help but see parallels between the moment Simon addresses and the twenty-first-century transformations wrought by streaming services like Spotify. Such sites have changed how music is produced and consumed, albeit with their own considerable set of costs. Now home to one of the world’s largest music catalogs, the algorithmic models that Spotify employs reward a select few despite promises of democratization. The vast majority, including many smaller labels and artists, find the musical economy that once sustained them destroyed. Moreover, if multitudes can be platformed, not everyone can be heard. Millions of songs on the platform have never enjoyed even a single stream.

In his sonorous history of the MP3—the format that gave rise to the peer-to-peer sharing system later co-opted by Spotify—Jonathan Sterne writes that, “unauthorized duplication and circulation have certainly deflated the profitability of recordings, but they are not the antimarket practices we have been led to believe.”[2] Whether in the case of the cassette or its successors, profit remains concentrated at the top and gatekeeping persists, even if following the money has become increasingly difficult.

Nonetheless, the crisis that almost always accompanies the introduction of new technologies to music, as Sterne suggests, “affords an opportunity to rethink the social organization of music.”[3] In cupping an ear to an earlier Egyptian iteration of this phenomenon, Simon provides readers just that opportunity and even supplies a format for doing so.

[Christopher Silver is the Segal Family Assistant Professor in Jewish History and Culture at McGill University]

Endnotes

[1] Walter Armbrust, Mass Culture and Modernism in Egypt (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), p. 180.

[2] Jonathan Sterne, MP3: The Meaning of a Form (Durham : Duke University Press, 2012), p. 28.

[3] Ibid, p. 27.