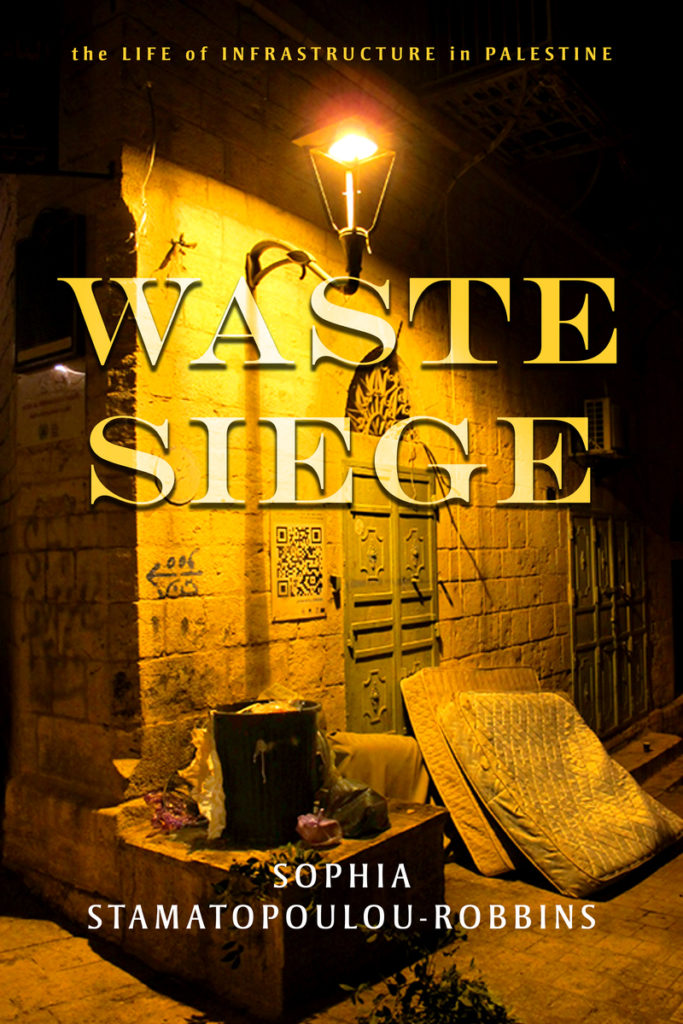

Stamatopoulou-Robbins’s book, Waste Siege: The Life of Infrastructure in Palestine, illuminates the ways in which waste and structures of waste management constitute and are constituted by the different authorities, mechanisms and ideologies that govern contemporary Palestine. The central theoretical intervention, waste siege, examines both the accumulation of waste within the Occupied Territories and the circulation of various wastes into and out of these spaces and the people who inhabit them. The concept of waste siege reveals the slow violence of exposure to waste while tracing the ways that waste challenges both local and academic understandings of ethical and political accountably.

Stamatopoulou-Robbins’s book, Waste Siege: The Life of Infrastructure in Palestine, illuminates the ways in which waste and structures of waste management constitute and are constituted by the different authorities, mechanisms and ideologies that govern contemporary Palestine. The central theoretical intervention, waste siege, examines both the accumulation of waste within the Occupied Territories and the circulation of various wastes into and out of these spaces and the people who inhabit them. The concept of waste siege reveals the slow violence of exposure to waste while tracing the ways that waste challenges both local and academic understandings of ethical and political accountably.

Your book Waste Siege: The Life of Infrastructure in Palestine began as your dissertation research. How has your thinking changed as you developed the dissertation into a book?

The dissertation focused on Palestinian Authority (PA) governance and how West Bank Palestinians responded to it. I was trying to understand what waste could tell us about the type of power the PA had after the Second Intifada. This was a moment when a lot of people were dismissing the PA as the body to which Israel had “subcontracted” the occupation, seeing the PA as a mere conduit for occupation that has no “content” of its own—as a body without the ability to affect the version of occupation (or life) that Palestinians were now experiencing. My focus on the cross-cutting issues and materialities of waste opened up new insights into long-standing debates about, and frameworks for understanding, Palestine and Palestinians’ experiences.

With the book, I decided that I wanted to reach people who don’t think much about Palestine—and here I am including non-academics as well. My goal was to offer an introduction to everyday experience in Palestine that will help readers see some aspects of life they may share with Palestinians, specifically experiences of waste, toxicity, consumption, morality and obsolescence, even as the book questions the universality of those experiences. The story that Waste Siege tells is certainly special and will not resonate with the experiences of many people who will read the book, for whom the ways in which violence and non-sovereignty affect the forms of inundation and the dilemmas that Palestinians experience are the stuff of ethnographies of distant, far less privileged, places.

I should say too that the chapter on bread (chapter 4) was entirely new to the book. I had thought about bread late during my initial fieldwork but, as I had been more concerned with the PA governance side of things, I had not found a way to include it in the dissertation. Including it in the book version opened up broader questions about ethics and morality, which are front and center in Palestinians’ experiences of unwanted bread. This led me to thread ethics and morality through the rest of the book in ways that I found very helpful, in part because those questions offered me a useful tool for thinking past the rather over-determining oppression/resistance, all-is-political, frameworks that dominate thinking about Israel/Palestine.

You write about the different scales of waste siege. Could you explain what you mean by that?

I was excited when I finally decided on the structure of the book, because I think it is able to convey an image of a small but powerful selection of scales of waste siege. These are the scales at which waste itself is thought about, managed or experienced, whether or not it constitutes a “siege.” We can break them down into social scales, institutional scales, spatial and territorial scales.

Social scales at which Palestinians experience waste siege range from the PA bureaucrat in Ramallah to the village council representative in a village like Shuqba, the construction worker, bakery owner and homemaker. Institutional scales include the Palestinian institutions I’ve mentioned but also Israeli institutions like ministries, the army, settler associations, environmental and other non-governmental organizations (NGOs), law firms, universities, international aid agencies and companies and Palestinian environmental and other NGOs. When you look at all of these actors from the perspective of waste siege, you see how they are assembled together by and through waste, even when they are on opposite political sides or when they do not actively cooperate with each other. You also see how they collaborate, even unwittingly, in the propagation of siege.

Spatially, their uneasy collaborations distribute wastes to different scales in contrasting ways. The experience of waste siege at the scale of a village surrounded by toxic wastes is analogous to, but also different from, the experience of waste siege at the scale of a home that is housing unwanted bread, and that is different from the scale of a person’s body, which moves through space, “housing” dioxins from trash burning.

The territorial scales are the ones my fieldwork—mostly based in the West Bank—allowed me to elaborate on the least. These are the scales of movement from the global and the regional into Palestine. For that, I would have liked to follow the process of manufacturing and exporting the goods that enter the West Bank (since so many products consumed in the West Bank are imported) from places like Israel, Turkey, Jordan, China. I would then have to follow the things as they “land,” circulate and, finally, become waste in Palestine. I am very excited that Kareem Rabie is working on a project that will look at the transfer process from China to Palestine and will illuminate some of the thought and bureaucratic processes, as well as the materialities, that make these circulations and accumulations possible. In other words, there is an empirical, global dimension to waste siege. Thinking about the global dimensions of what comes to be thought of as Palestinian waste could extend to thinking, too, about the origins and transformations of certain waste management logics that have become dominant in Palestine. These have sources in places like the United States, Japan and Germany. They arrive in Palestine in part through the expertise of globally circulating Palestinian engineers as well as through the highly conditional funds the PA is “offered” to build the infrastructures for managing Palestinian wastes.

The relationship between accountability and politics is a theme throughout the text. The reader sees the difficulty of assigning blame and assessing the limits of harm of waste (what you call waste’s murky indexicality) meeting up with the variegated nature of political authority in the West Bank. How does understanding the difficulty of assigning responsibility for various aspects of waste siege help us to understand the state in new ways?

Thank you for asking this. I was definitely thinking a lot about the state from the beginning of this project and noticing how theories of the state I was encountering did not totally capture what I was seeing in Palestine. Two things really stuck out to me in Palestine. One, Palestinians sometimes referred to the occupation in the past tense even while speaking in the same breath about how it oppresses them in the present. And two, that accountability for waste seemed to be unclear or confusing to a group of people for whom identifying the source of their own experiences of injustice has long been somewhat straightforward (even too straightforward, some critics, like Palestinian feminists and Marxists, might say). In other words, Israel or the occupation have taken center stage in thinking about accountability for a long time. The state can be experienced through its failure. This is something that observers of the Middle East are increasingly thinking about (e.g. with Lebanon’s garbage crisis, and Joanne Nucho’s work on infrastructure in Beirut) and that Lisa Wedeen proposed in her earlier work on Yemen.

But what I found that interested me was that something can be experienced as state-like even when failure is not entirely, or always, attributed to it. The state can have a smell (such as the smell of burning trash) because that smell is the smell of a specific institution’s jurisdiction (e.g. the PA). That jurisdiction is actually the collective, or temporally fragmented, jurisdiction of many institutions—the Israeli military, NGOs, community organizations—and actors, such as obsolescent commodities and their consumers. In other words, the PA is a condition of being for all these institutions and actors intersecting to create a waste siege. Waste siege and PA governance become superimposed, or conflated, into an experience that I call the “phantom state,” following my interlocutors, but that could be called the waste-siege-state. I think of this as an addendum to Audra Simpson’s theory of “nested sovereignty.” The waste-siege-state is different from nested sovereignty first because I think Simpson finds some hope in it, and I am not sure that I find that same hope in the phantom state effect. Second, the concept of the waste-siege-state forces us to think about the various materialities, flows and affective experiences that produce experiences of (semi)sovereignty. And third, it presents a case of “nestedness” where the settler colonial state is always also a part of the nested, colonized sovereignty, as are transnational actors like foreign aid agencies and local, non- (and even anti-) governmental actors like NGOs.

How do the varieties and forms of waste that you cover (landfills, disposable goods, secondhand items, unwanted bread and sewage) and the different scales at which you examine them, hang together? Why did you choose these particular forms of waste?

These very different forms hang together through the fact that they generate what we can think of as unresolvable dilemmas. They are the remains of human activities that humans would prefer not to think about, but that force themselves into human thought and practice by virtue of the various specific constraints imposed on them and on Palestinians by the twentieth century version of non-sovereignty in which Palestinians live. The fact that they trigger ethical dilemmas unites them.

The other thing that unites them is that they are all very obviously material, physical forms of waste. I say this because there was a moment early in my fieldwork when I considered including other forms of waste generated by the occupation, such as waste of time (like at checkpoints) and waste of skill (with high unemployment in an occupied economy full of highly educated Palestinians).

Returning to Waste Siege, I also want to note that, counterintuitively, in the chapter on secondhand goods (chapter 2), the source of people’s dilemmas is initially not the secondhand goods themselves, even while they can be classified as a form of waste. Rather, what causes people distress are the unused commodities purchased in the firsthand market, whose planned obsolescence creates dilemmas of consumption and frustrations about the wasting of money and experiences of unreliable product regulation. Here secondhand goods smuggled into the West Bank from Israel and therefore perceived to be of higher quality (and more “lasting”) become solutions to Palestinians’ inundation with bad new goods. This example helps me tell the larger story I’m trying to convey in the book, which is that under waste siege, waste serves many purposes. It creates the dilemmas and frustrations I mentioned but it also becomes a currency for navigating the economies it produces, an infrastructure for its own resolution. It is recycled, but never without leaving a trace of its more problematic characteristics or opening up new opportunities for additional ones.

Your current research is on the Airbnb phenomenon in Greece. Can you give us a brief preview of the new project, and share any threads that connect the two projects?

Two of my next projects are connected to platform-mediated home sharing. One, which I am calling Homing Austerity: Airbnb in Athens, seems very different on the face of it, but there are a couple of things I think connect to the first book. One is that I happened to be in Greece when capital controls were imposed. Suddenly Germany’s political leadership decided, for example, how much money Greeks could get out of an ATM. This also applied to Greeks who were abroad and were trying to draw money from a foreign ATM from their Greek bank accounts. I thought, “This is occupation.” My experience having worked on the occupation of Palestine gave me a sense of comparison that maybe wouldn’t normally come to mind. The austerity governance was one very striking example where an extraterritorial force comes in and changes the way that a place operates. In came the austerity measures that were basically just shoved through the Greek parliament to transform the way the government, the state and Greek society worked, including through privatization of major infrastructure like the seaports, airports and utilities. It was happening so quickly and so universally across the territory that it really felt like I was seeing a sudden occupation.

Meanwhile, the commentaries about Greece were centered on the economy, of course, and on the way that the economy was being destroyed. We saw labor being made more precarious and pensions slashed. It was easy, especially from the perspective of the left, to tell only a declensionist story: Greece as we knew it was being destroyed. While essential aspects of this story are true, as we know from other places like Palestine, much is generated out of situations of apparent destruction. So, I wanted to understand what is being generated under our noses in the new austerity that became the reality in Greece. One of the things I found was that Airbnb was flourishing at the exact same time as the economy was being devastated. Something new was happening that I wanted to track down. In some ways, this parallels the first book in that I’m interested in what is generated out of what looks like ruination.

Another thing that I think is going to overlap a lot more than I expected between my book and this new project is a discard studies approach to both places. Being ensconced in the discard studies world, I am paying more attention to the fates of infrastructures and objects and the logics according to which they get valued, moved around, created or destroyed. For example, I’m excited that one of the chapters will probably be about decluttering in the designing of Airbnb properties and the kind of changes in value to movable and immovable property that Airbnb is part of. That seems like an exciting new approach to Airbnb, which has otherwise been thought about primarily in terms of precaritization and gentrification. The lens of property and objects will help me to tell what I am thinking about as the back story of Airbnb. The look at property and objects is also going to help me think about kinship, which I’m really excited about and which only appeared in passing in my first book. Similarly, thinking about the scale of the household was a bit of a missed encounter for me in the Palestine book.

[Tessa Farmer is an assistant professor in the Middle Eastern and South Asian Languages and Cultures Department and the Global Studies Program at the University of Virginia.]