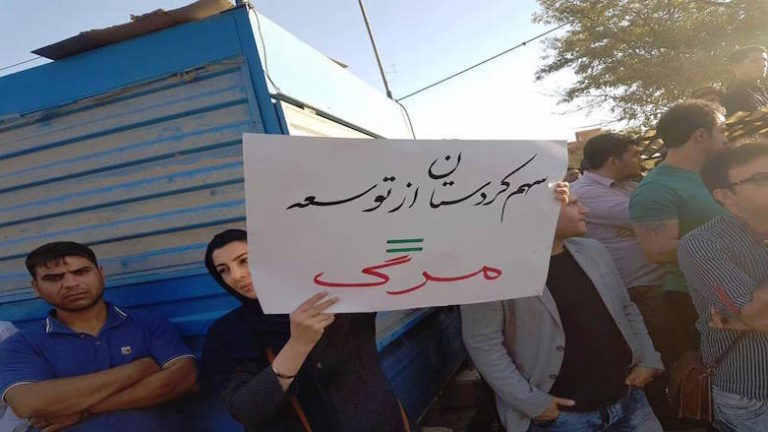

A Kurdish protestor holds a sign that says, “Kurdistan’s share of development is death,” referring to the Iranian president’s promises for economic development. Mariwan, Iran, October 6, 2016. Courtesy Kurdistan 24.

The Kurds in Iran have been engaged in a century-long struggle against sovereign authority in Tehran. While armed insurgency has been one element of Kurdish politics in Iran—especially in the late 1940s, 1970s and 1980s—the Kurds’ response over the past 40 years to the state’s authoritarian policies in Kurdistan has also taken the form of civic activism, especially in the spheres of publishing, language instruction and environmental activism.

The Kurds’ central demand is autonomy and the right of self-determination within the legal and political framework of a democratic Iran, which has been the main objective of the Kurdish struggle since the Iranian revolution. For example, the Kurdish movement, especially its leading political organization the KDPI, framed its claim for national rights in terms of democracy for Iran and autonomy for Kurdistan (Demokrasi beray Iran, khodmokhtari beray Kordestan). The state, which represses Kurdish social and political activity as a threat to Iran’s national security, rejects this call outright.[1] In the absence of legal political parties in Iran, Kurdish civil society (which refers to associations that are legally recognized by the local, provincial and central government) has had to innovate new methods of resistance to authoritarian rule, even though the securitized nature of Kurdish-state relations has made this task extraordinarily challenging.

The conflict between state institutions and Kurdish environmental groups in particular reveal competing approaches to economic development, sustainability and security. Environmental activists denounce the government’s industrial and development policies in Kurdistan as unsustainable, overly state-centric and detrimental to the natural environment, leaving the Kurdish region even further underdeveloped and deprived. The state responds to environmental activism as if to a security threat, using harsh measures such as imprisonment and executions.

The Rapid Expansion of Kurdish Civil Society

The election victory of reformist clergyman Mohammad Khatami in May 1997 and his two consecutive presidential terms (1997 to 2005), is often referred to as the moment of the birth of Iran’s contemporary reform movement.[3] Supporting the reformist front at the ballot box was one of the ways Kurds expressed their support for democratization of the state—specifically, the de-centralization of power and greater transparency, meritocracy and rule of law. Many candidates from Kurdish reformist groups were elected to the Iranian parliament in the sixth election (2000). In the seventh general election in 2004 however, Kurdish reformists, like other reformist groups, were shut out of parliament when the Guardian Council stepped in to vet, and reject, reformist candidates, which led to a decline in voter turnout.

Resistance Through Language and Culture

The new civil society organizations bring public attention to domestic violence, criticize the state’s approach to child marriage and child brides and point out the poor condition of schools and educational institutions in Kurdistan. They also campaign for education in Iranian schools to be conducted in Kurdish and other languages other than Persian, which is promised by the constitution but was never instituted. Since the early twentieth century, Kermashan province (particularly its capital city Kermashan) has been at the center of the state’s linguistic assimilation policies in Kurdistan. Promoting Persian as the only medium of educational instruction has been deployed by the Islamic republic and its predecessor regimes. The state attempts to enforce this policy through intimidation and arrests: In July 2020, Zahra Mohammadi, a Kurdish-language teacher in Sanandaj, was arrested and given a ten-year sentence for her activism. Kurdish resistance to language policy is also not unique to the post-revolution era, as Kurdish manuscripts from the eighteenth century attest: The legendary Kurdish poet Khana Qubadi (1700-1759) stated in a poem, “even though they say that Persian is sugar, for me Kurdish is sweeter.”[5]

Student publications in particular have become a platform to denounce the government’s socioeconomic policies in Kurdistan. They describe state-Kurdish relations in Iran as a center-periphery relationship, where the center not only neglects the rights of Kurds, but also actively attempts to assimilate Kurds and marginalize their culture and identity.

]Kurdish identity in Iran is being reconstructed through an emphasis on identity and raising consciousness. For instance, Kurds are commonly referred to by the state as an Aryan people that shares historical roots with Persians. However, bilingual media produced by Kurdish students has taken a starkly different line over the last two decades. Activists assert that “we have to reclaim our identity and reframe the identity of our land and cities” and point to the Kurdishness of cities such as Kermashan, the city with the largest Kurdish population in Iran.[7] The promotion of a self-defined form of Kurdish identity, distanced from the state-promoted form of Iranian identity (that draws upon Aryanism and Shi’ism) is a visible element of these publications. Referring to the Kurds as “the people of Zagros,” a terrain with different geographical, cultural and social characteristics to southern, central and eastern Iran, this self-identification proclaims the historical difference between Kurdish and Persian identity.

Environmentalism in the Defense of Kurdistan

Environmental activism is another significant trend among Kurds in Iran, especially over the last decade: Almost every city in Iranian Kurdistan now has its own environmental society. The Kurdistan Green Association, Environmental Protectors of Wllat, the Chya Green Association and the Association of Green Thinkers are examples of environmental NGOs and associations that are campaigning for the protection and preservation of Kurdistan’s natural environment. Awareness campaigns, such as documenting the destructive impact of dams, clear-cutting and deforestation, are a major activity of these associations.[8] Criticizing and challenging the state’s industrial and military projects in Kurdistan and their degrading effect on nature are further aspects of Kurdish environmentalism.

Local mobilizations against environmentally damaging activities include several peaceful mass demonstrations organized by Chya to protest the IRGC’s plan to construct an oil refinery next to Lake Zrebar. Chya mobilized up to 15,000 protesters from Mariwan and the surrounding areas in February 2015 to march from Mariwan toward Zrebar. Due to the substantial size of the protest, the IRGC cancelled the project, or at least delayed it indefinitely.[10] Chya also organized the Save Kani Bel Campaign in 2016, which involved 3,000 individuals and a host of local NGOs. The protests against the construction of a dam on Kani Bel, a natural spring in Kermashan province and a symbol of Kurdish identity and culture, included a hunger strike by ten environmental activists.[11] Despite their protest and campaigns, major elements of the Daryan Dam, constructed on Kani Bel and Sirwan River, were completed in 2018.

The magazine Chya has been an important platform for criticizing the state’s approach to development and sustainability. The environmental activist, Amin Azizi, reports on government activities such as the construction of dams and oil refineries and demands that any development in Kurdistan should consider the environment and adopt “a model of environmental security defined by this region’s population.”[12]

These tense relations between the politicized and active sections of Kurdish civil society and the Iranian government have further exacerbated the poor relationship between the state and the Kurds in Iran. The main result is deeper securitization and militarization of the Kurdish region by the state’s security and judicial institutions. Some state officials have also labelled Kurdish environmental activists as “anti-development” to justify their persecution and imprisonment by the state. For instance, Mariwan’s governor, Mohammad Kiyani—in reaction to protests by local environmental activists of the authorities’ mismanagement of environmental issues and pursuit of environmentally degrading development activities in Mariwan—called them the “actions of individuals with political motives and actions hampering local development.”[13]

The securitization of environmentalism is a countrywide issue and not necessarily limited to the Kurdish region. The mysterious death of the environmental scientist Kavous Seyed Emami, co-founder of the Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation, in Evin prison, as well as the plane crash and deaths of 16 environmentalists flying from Tehran to Yasuj on February 18, 2017, are examples of the difficult conditions facing environmental activists across Iran. As shown in recent studies, however, the extent to which the state responds to activists as a security threat varies by region.[14] Long-term imprisonment, executions and, in some cases, cold-blooded assassinations of civil society and environmental activists conducted by the IRGC are among the dangers faced by Kurdish civil society. While there are few concrete signs of alliances being built across ethnic and regional boundaries at this moment, it is clear that this possibility frightens the central government and could/should be part of the struggle to build a more democratic Iran and autonomy for Kurds.

[Allan Hassaniyan is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Centre for Kurdish Studies at the University of Exeter.]

Endnotes

[1] Abbas Vali, The Forgotten Years of Kurdish Nationalism in Iran (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), p. 39.

[2] Nader Entessar, “The Kurdish Mosaic of Discord,” Third World Quarterly 11/4 (October 1989), and Farideh Koohi-Kamali, The Political Development of the Kurds in Iran: Pastoral Nationalism (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003).

[3] Ali Gheissari and Vali Nasr, Democracy in Iran, History and the Quest for Liberty (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. 128–131.

[4] The Kurdistan Democratic Student Union (2005), People’s Message (Payam-e Madoom, 2003) and The Human Rights Organization of Kurdistan/RMMK (Rekxerawi Mafe Mirovi Kordestan, 2005) are examples that were established during the so-called reform era. The RMMK was later declared illegal and the founder, Kurdish lawyer and journalist Mohammad Seddigh Kaboudvand, was arrested in 2007 and served ten years in prison.

[5] Khana Qubadi, “Even though they say that Persian is sugar, for me Kurdish is sweeter,” Srwa 1/1 (1985), p. 3. [Kurdish]

[6] Ayub Mohammadnejad, “Why Highway, Railway and Prosperity Does not Reach Kurdistan,” Ruwange 12/9-10 (Winter 2018). [Kurdish]

[7] Porya Almasi, “Zagros’ Gold at the Rate of Silver,” Kermashan 1/5 (2016), p. 8. [Kurdish]

[8] Hayder Rohi, “Dams Destructive Impact on the Environment,” Chya Sociocultural Monthly 1/2 (December 2015), p. 3. [Kurdish]

[9] Allan Hassaniyan, “Environmentalism in Iranian Kurdistan: Causes and Conditions for its Securitisation,” Conflict, Security and Development, 20/1 (2020).

[10] Author’s interview with environmental activist, Farzad Haghshenas, May 22, 2020.

[11] Dlniya Rahimzadeh, “Kani Bel, National Treasure,” Rwange 1/1 (January 2016). [Kurdish]

[12] Amin Azizi, “Dams: Development and Progress or Questionable Steps?” Biweekly Chya 3/67 (September 2011). Amin Azizi, “Security and the Rights of Ethnonational Groups,” Chya Sociocultural Monthly 1/6 (April 2016). [Kurdish]

[13] Biweekly Chya 52 (November 2010), p. 2. [Kurdish]

[14] Hassaniyan, “Environmentalism in Iranian Kurdistan.”