Palestine and Israel—A Primer

Joel Beinin and Lisa HajjarThis primer provides an overview of key actors, organizations, historic events, political developments and diplomatic initiatives that have shaped the status and fate of Palestinians and the State of Israel from the late nineteenth century to the present. It is divided into topical sections and organized roughly chronologically—although some topics cannot be neatly contained in a chronological frame. It offers a basic understanding and an entry point. Readers may explore the website of the Middle East Research and Information Project (www.merip.org/search) for materials that examine issues more deeply and address topics treated only briefly or omitted here.

The Land, Peoples and Ideologies

The conflict between Palestinian Arabs and Zionist (now Israeli) Jews is a modern phenomenon, originating at the end of the nineteenth century. Although the two groups have different religions (Palestinians include Muslims, Christians and Druze), the cause of the contention is ethno-national rather than religious differences. The conflict began as a struggle between Jewish immigrant settlers and local Arab inhabitants over land, labor markets and eventually political control of Palestine. Before World War I, Palestine was a territory with indefinite boundaries long known by the three monotheistic religions as the Holy Land. From the end of World War I until 1948, the area was governed by Britain under a Mandate from the League of Nations. Following the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, this land was divided into three parts: the State of Israel, the West Bank (of the Jordan River) and the Gaza Strip. The city of Jerusalem was divided with the eastern half adjoined to the West Bank and the western half becoming part of Israel.

It is a small area—approximately 10,000 square miles, or about the size of Belgium or the US state of Maryland. Jewish claims to this land are based on God’s promise to Abraham and his descendants narrated in the biblical Book of Genesis, on the history of the land as the site of the ancient Israelite kingdoms and temples in Jerusalem and on European Jews’ need for a haven from antisemitism. Palestinian Arab claims to the land are based on their long-term continuous residence in the country and the fact that they constituted the demographic majority until 1948. Palestinians reject the notion that a biblical-era kingdom constitutes the basis for a valid modern claim. They do not believe that they should forfeit their land or compromise their political rights to compensate Jews for Europe’s crimes against the Jewish people, culminating in the Holocaust (or Shoah).

Until World War I, Palestine was part of the Ottoman Empire, but it did not constitute a single political unit. The northern districts of Acre and Nablus were part of the province of Beirut. The district of Jerusalem was under the direct authority of the Ottoman capital of Istanbul because of the international significance of the cities of Jerusalem and Bethlehem as religious centers for Muslims, Christians and Jews. According to the 1878 Ottoman census, the Jerusalem, Nablus and Acre districts had a population of 472,465 subjects: 403,795 Muslims (including Druze), 43,659 Christians and 15,011 Jews. In addition, there were perhaps 10,000 Jews with foreign citizenship (recent immigrants to the country) and several thousand nomadic and semi-sedentary Arabs (Bedouin) who were not counted in Ottoman-era demographic data. The great majority of the Arabs (Muslims, Christians and Druze) lived in several hundred rural villages. Jaffa and Nablus were the largest and economically most important towns with majority-Arab populations.

In the nineteenth century, following a trend that emerged earlier in Europe, people around the world began to identify themselves as nations and to demand national rights, foremost the right to self-rule in a state of their own (self-determination and sovereignty). Jews and Palestinian Arabs both started to develop a national consciousness and mobilized to achieve national goals. Some European Jewish nationalists considered the regions of Eastern Europe, where Jews spoke Yiddish, as their homeland. In contrast, Zionists sought to identify a place outside Europe where Jews could become territorially concentrated through immigration and settlement. As Zionist ideology and organizations were being formulated, millions of Jews emigrated from Europe to other locations (mostly the Americas).

Palestinian Arabs were always conscious of themselves as living in the Holy Land. The 1908 Ottoman Constitutional Revolution, which restored the parliament, freedom of the press and political expression, provided the intelligentsia with platforms to articulate their opposition to Zionist settlement. In its wake, conflict with Zionist settlers over access to agricultural land intensified, accelerating the processes that contributed to the formation of a modern Palestinian Arab national identity. That identity and a nationalist movement in opposition to Zionism crystallized during and in the immediate aftermath of World War I.

Until the beginning of the twentieth century, most Jews living in Palestine were concentrated in four cities with religious significance: Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed and Tiberias. Many of them observed traditional (orthodox) religious practices and spent their time studying religious texts. They depended on the charity of world Jewry for survival. Their attachment to the land was religious rather than national, and they were not involved in—or supportive of—the Zionist movement that began in Europe and was brought to Palestine by immigrants. In these four cities and in Jaffa there was also a significant Arabic-speaking Spanish (Sephardic) Jewish population who had resided in Palestine and the Ottoman Empire following their expulsion from Spain in 1492.

The most prominent leader of the nascent Zionist movement was Theodor Herzl, who promoted the national project in his book Der Judenstaat (The Jews’ State) and founded the World Zionist Organization. Although Herzl and other Zionists considered other locations (Herzl preferred Argentina), over time Palestine seemed the logical and optimal place because of its historical and religious significance for Jews.

Herzl and his successor as the head of the World Zionist Organization, Chaim Weizmann, focused their efforts on gaining support for the Zionist project from European imperial powers. Labor Zionists, of whom the most prominent was Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, adapted socialist or social democratic ideas to the Zionist project. Vladimir Jabotinsky led the Revisionist Zionists, the forerunners of today’s Likud. Revisionists advocated that the Zionist movement should make the creation of a Jewish state on both sides of the Jordan River its unequivocal goal and that it would be necessary to build up a military force to defend the Zionist settlement project from Palestinian Arabs who would never accept it. They admired Italian fascist leader Benito Mussolini until he allied with Hitler in 1936 and broke strikes of Jewish workers. Cultural Zionists, like Ahad ha-‘Am, prioritized the revival of Hebrew culture and opposed focusing on mass settlement and a state.

The first wave of European Jewish immigration to Palestine (termed ‘aliyah, in Zionist parlance, from the Hebrew for “going up”) began in 1881. Only with the second ‘aliyah (1904–1914), however, did significant numbers of ideologically committed Zionists come to Palestine. Most of the Jews who emigrated from Europe beginning in the late nineteenth century lived a secular lifestyle and were committed to the goals of creating a modern Jewish nation-state. At the outbreak of World War I (1914), the population of Jews in Palestine had risen to about 60,000 (about 8 percent of the population). Some 36,000 were recent immigrants, about half of whom resided in agricultural settlements. The Arab population at the time was 683,000.

Settler Colonialism

Palestinian Arabs have long regarded Zionism as a colonial project promoted by Britain since 1917 and, after the establishment of the State of Israel, by other Western powers. This view is exemplified by Fayez Sayegh’s 1965 book, Zionist Colonialism in Palestine. In the 1990s many scholars, most prominently the late Patrick Wolfe, came to understand settler colonialism as a distinct form of European overseas expansion. In settler colonies Europeans did not seek only to extract mineral or agricultural resources, establish a military base or commercial entrepot, or impose unequal terms of trade, as in British India, the British Crown Colony of Aden, the British protectorates of the Persian Gulf, French Indochina or Belgian Congo. Rather, European settlers sought to displace or entirely eliminate previously existing local populations. Examples of settler colonialism include the former British colonies in North America, Australia, New Zealand and Kenya, the former French colonies of Algeria and Tunisia and the short-lived Italian conquest of Libya.

Herzl and other early Zionist leaders adopted the strategy of colonial settlement as the only way to establish a large, primarily European, Jewish community in Palestine. Until the post-World War II era of accelerating decolonization, Zionists of all political tendencies commonly used the terms “settlement” and “colonization” for their project and described their settlements in Palestine as colonies. The Jewish Colonial Trust (1898) and the Colonization Commission (1898) were early Zionist organizations. These terms were uncontroversial in an era when Europeans and North Americans presumed that they had a right, and even a duty, to conquer and settle lands beyond their borders and impose their rule on the indigenous inhabitants.

The social structures, cultures and trajectories of settler colonial projects vary. Many Northern Europeans who settled in the 13 American colonies in the seventeenth to eighteenth centuries were escaping religious persecution. As white populations increased in North America and Australia, settlers carried out large-scale genocides against indigenous populations. In Algeria and South Africa settlers seized the lands of Muslims and Black Africans, respectively, but did not eliminate them. Rather, they employed the indigenous populations as cheap labor in agricultural and mining enterprises. Afrikaners who descended from seventeenth-century Dutch settlers believed that South Africa was their promised land. Italian settlers in Libya believed they were restoring the heritage of ancient Rome. After Algeria and Tunisia achieved independence from colonial rule, the vast majority of European settlers resettled in metropolitan France. Zionist settlers in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries sought to escape antisemitism in Europe and believed that they were returning to their ancient homeland and reclaiming their birthright in Palestine. There is no contradiction in understanding Zionism as simultaneously a nationalist movement and a settler colonial project.

Gaza, circa 1920s. American Colony Photo Department, Matson Collection, Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/2019712823/

The British Mandate in Palestine

Over the course of the nineteenth century, the Ottoman Empire was weakened by wars with European powers and the spread of nationalism throughout its regions. Its Arab areas emerged as sites of competing European territorial claims and interests. By the early twentieth century, European powers were competing to occupy or extend their influence over areas along the eastern Mediterranean (known as the Levant), including Palestine. These efforts were dramatically accelerated by World War I in which the Ottoman Empire was aligned with Germany and the Central Powers against the Allied Powers of Britain, France, Russia (until the 1917 revolution) and, later, Italy and the United States.

During 1915–1916, as World War I was underway, the British high commissioner in Egypt, Sir Henry McMahon, secretly corresponded with Husayn ibn ‘Ali, the patriarch of the Hashemite family and Ottoman governor of Mecca and Medina. McMahon convinced Husayn to lead an Arab uprising against the Ottoman Empire by promising that if the Arabs supported Britain in the war, the British government would support the establishment of an independent Arab state under Hashemite rule in the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire, including Palestine. The Arab Revolt began in June 1916 and was led by Husayn’s son Faysal. In the West it is popularly identified with the British officer T. E. Lawrence (also known as Lawrence of Arabia). The revolt distracted and weakened the Ottoman war effort from within and thus contributed to the defeat of the Central Powers.

Britain made other promises during the war that conflicted with the Husayn-McMahon correspondence. In May 1916 Britain and France secretly negotiated the Sykes-Picot Agreement to carve up the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire and divide control of the region between themselves. And in November 1917, British Foreign Minister Arthur Balfour, at the behest of Prime Minister David Lloyd George and in coordination with Zionist leaders in Britain, issued the Balfour Declaration announcing his government’s support for the establishment “in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.” As with Britain’s instigation of the Arab Revolt, Lloyd George hoped to change the dynamics of the war. He and other British officials believed that a pro-Zionist statement would rally Jews in Germany, Russia and the United States to help the British war effort. These three contradictory promises—Husayn-McMahon Correspondence, Sykes-Picot Agreement and Balfour Declaration—were primarily intended to benefit British imperial and military interests, not Arabs or Jews.

After the Allies’ victory in World War I, Britain and France, which effectively controlled the new League of Nations (precursor to the United Nations), granted themselves mandates, a form of neo-colonial rule, over the former Ottoman Arab territories. France obtained a mandate over Syria and carved out Lebanon as a separate state with a (slight) Christian majority. Britain obtained one mandate over Iraq and another over Palestine, which included the area that now comprises Israel, the West Bank, the Gaza Strip and Jordan.

In 1921, Britain divided its Palestine mandate into two territories. The territory to the east of the Jordan River became the Emirate of Transjordan, to be ruled by Faysal’s brother Abdullah. The territory to the west of the Jordan River became British Mandate Palestine. Britain envisioned that its commitment to promote a Jewish national home would be restricted to that region (but importantly, that not all of Palestine would become a Jewish state). For the first time in modern history, Palestine became a geographically bounded political entity. British Mandate Palestine between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea is often referred to as historic Palestine, although its political borders were established in 1919–1922.

Throughout the region, Arabs were angered by Britain’s failure to fulfill its promise to create an independent Arab state, and many opposed the British and French mandates as a violation of Arabs’ right to self-determination. The rising tide of mainly European Jewish immigration, land purchases and settlement in Palestine generated increasing resistance by indigenous Palestinians. They opposed the influx of Jews because they feared it would threaten their position in the country and lead eventually to the establishment of a Jewish state that would thwart their aspirations for self-determination.

In the 1920s, the Jewish National Fund (a Zionist land-purchasing agency) bought lands from absentee Arab landowners, many of whom lived in Beirut, Damascus or Jaffa. Since the goal was to settle Jewish immigrants on those lands, the Zionist authorities required that Palestinian tenant farmers who had worked and lived on them be evicted. These displacements led to increasing tensions and violent confrontations between Jewish settlers and uprooted peasant tenants. In 1920 and 1921, clashes broke out between Arabs and Jews in which roughly equal numbers from both communities were killed.

Tensions intensified in 1928 when Muslims and Jews in Jerusalem began to clash over their respective communal religious rights at Jerusalem’s holy sites. The Western Wall, the sole remnant of the second Jewish Temple, is the holiest site in the Jewish religious tradition. Above the Wall is a large plaza revered by Jews as the Temple Mount—the location of the two ancient Israelite temples. The Muslim connection to Jerusalem dates to the origins of the faith. It was the first direction of prayer (qibla). Abraham, David, Solomon and Jesus, who are all associated with Jerusalem, are prophets in the Muslim tradition. The plaza, which hosts al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock, is called the Noble Sanctuary (al-Haram al-Sharif). Muslims believe that the Prophet Muhammad tethered his winged horse, al-Buraq, to the Western Wall, which bears the horse’s name in the Muslim tradition, before ascending to heaven from the Dome of the Rock.

On August 15, 1929, supporters of the Betar Revisionist Zionist youth movement marched to the Western Wall chanting “the Wall is ours” and raised the Zionist flag over it. Fearing that the Noble Sanctuary was in danger, Muslims responded by attacking Jews in Jerusalem, Hebron and Safed. Among the dead were 64 Jews in Hebron. Their Muslim neighbors saved many others. The Jewish community of Hebron ceased to exist when its surviving members left for Jerusalem. During a week of communal violence, 133 Jews and 115 Arabs were killed and many more were wounded.

European Jewish immigration to Palestine increased dramatically after Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in Germany in 1933, leading to new land purchases and bolstering the Jewish community (known as the yishuv). Palestinian Zionist leaders concluded the “transfer” (ha-‘avarah) agreement with Nazi Germany to permit German Jews to immigrate to Palestine with a portion of their capital in exchange for Zionist purchases of German manufactured goods. Palestinian resistance to British control and Zionist settlement climaxed with the Arab Revolt of 1936–1939, which involved not only Palestinians but also Arabs from across the region. Britain violently suppressed the revolt with the help of Zionist militias and the complicity of neighboring Arab regimes.

After crushing the Arab Revolt, the British reconsidered their policies in an effort to maintain order and to try to secure Arab support as a new war in Europe loomed. In 1939, Britain issued a White Paper (a statement of government policy) limiting future Jewish immigration and land purchases and promising independence in ten years, which—had it been fulfilled—would have resulted in a majority-Arab Palestinian state. The Zionists regarded this policy shift as a betrayal of the Balfour Declaration.

The 1939 White Paper marked a major disruption of the British-Zionist alliance. With the start of World War II, the main Zionist parties helped the British war effort while the small right-wing LEHI (Fighters for the Freedom of Israel) initiated a decade-long militant insurgency against British rule. At the same time, the British-Zionist defeat of the Arab Revolt and arrest, killing or exile of the Palestinian political leadership left Palestinians politically disorganized during the crucial decade in which the future of Palestine was decided.

The United Nations Partition Plan

After World War II, hostilities escalated between the Zionist militias and the British colonial administration. Britain was unable to prevent the many bloody attacks, bombings, kidnappings and assassinations of its military and civilian personnel by Zionist groups or to staunch the instability in the countryside. In 1947 Britain relinquished its mandate over Palestine and requested that the recently established United Nations determine the future of the country. The British government hoped that the UN would be unable to arrive at a workable solution and would turn Palestine back to its control as a UN trusteeship.

At the time, 1,269,000 Arabs and 608,000 Jews resided within the borders of Mandate Palestine. Through land purchases, Jews had acquired 6–7 percent of the total land area, amounting to about 20 percent of the arable land. Arabs owned about 48 percent of the land. Another 46 percent was classified as state-owned lands, a designation dating to the era when the Ottoman sultan formally held the title to most agricultural lands and the Naqab/Negev desert.

A UN-appointed committee of representatives from various countries went to Palestine to investigate the situation. Committee members disagreed on the form that a political resolution should take. But the majority concluded that the country should be divided (partitioned) to satisfy the needs and demands of both Jews and Palestinian Arabs.

On November 29, 1947, the UN General Assembly voted to partition Palestine into a Jewish and an Arab state. The UN Partition Plan envisioned that each state would have a majority of its own population. Although Jews comprised one-third of the population, the UN Partition Plan designated 43 percent of the land of Palestine for the Arab state and 56 percent, including most of the fertile coastline, for the Jewish state on the assumption that large numbers of Jews would immigrate there. Few Jewish settlements were located in the proposed Arab state, but hundreds of thousands of Palestinian Arabs were to become part of the proposed Jewish state. The area of Jerusalem and Bethlehem was to become an internationally administered zone.

Publicly, most of the Zionist leadership accepted the UN Partition Plan, although some, notably David Ben-Gurion (the future first prime minister of Israel), hoped to expand the borders assigned to the Jewish state in the event of a war. The Palestinian Arabs and the surrounding Arab states rejected the UN plan and regarded the General Assembly vote as an unacceptable violation of the Palestinian right to self-determination. Some argued that the UN plan allotted too much territory to the Jews.

Most Arabs regarded the proposed Jewish state as a settler colony. They argued that it was only because the British had (until the 1939 White Paper) sponsored extensive Zionist settlement in Palestine against the wishes of the Arab majority that the question of Jewish statehood was on the international agenda at all.

Haganah fighters expel Palestinians from Haifa. May 12, 1948. (AFP/Getty Images)

The 1948 Arab-Israeli War

Fighting between the Arab and Jewish-Zionist residents of Palestine began immediately after the adoption of the UN Partition Plan. The Palestinian Arab military forces were poorly organized, trained and armed. In contrast, Zionist military forces had built strength during the Mandate and were well organized, trained and, eventually, well-armed.

On May 15, 1948, the British completed their planned evacuation of Palestine. Zionist leaders proclaimed the State of Israel on May 14, the eve of the British evacuation. That event is commemorated according to the date on Hebrew calendar, the 5th of Iyar. By that time, the Zionist military forces had secured control over much of the territory allotted to the Jewish state in the UN plan except for the Negev/Naqab desert. By late April 1948 they began to go on the offensive, conquering territory beyond the partition borders in several sectors. For Palestinians, May 15 is commemorated as Nakba (catastrophe) Day because it marks a profound political loss and the acceleration of mass exodus and expulsions from their homeland.

Military forces from neighboring Arab states (Egypt, Syria, Jordan and Iraq) entered Palestine to prevent the establishment of a Jewish state. Some Arab rulers were no more anxious than the Zionists to see an independent Palestinian state. King Abdullah of Transjordan, who had territorial designs of his own on Palestine, had been engaging in secret negotiations with Zionist leaders to divide Palestine between them. Consequently, Jordanian troops played only a limited role in the war in the Jerusalem sector and held their positions in the hills (areas that became the West Bank). During May and June 1948, when the fighting was most intense, the outcome of the war was in doubt. But after Soviet-approved arms shipments from Czechoslovakia reached Israel, Israeli armed forces conquered additional territories beyond the borders that had been designated by the UN Partition Plan.

In 1949, the first war between Israel and the Arab states ended with the signing of armistice agreements, signifying “no war, no peace.” The territory of British Mandate Palestine was now divided into three parts, each under a different political regime. The boundaries between them were the 1949 armistice lines (the Green Line). The State of Israel encompassed over 77 percent of the territory. Jordan occupied East Jerusalem and the hill country of central Palestine (henceforth designated as the West Bank and annexed by Jordan in 1950). Egypt administered the coastal plain around the city of Gaza (the Gaza Strip) but did not annex it. The Palestinian Arab state envisioned by the UN plan was never established.

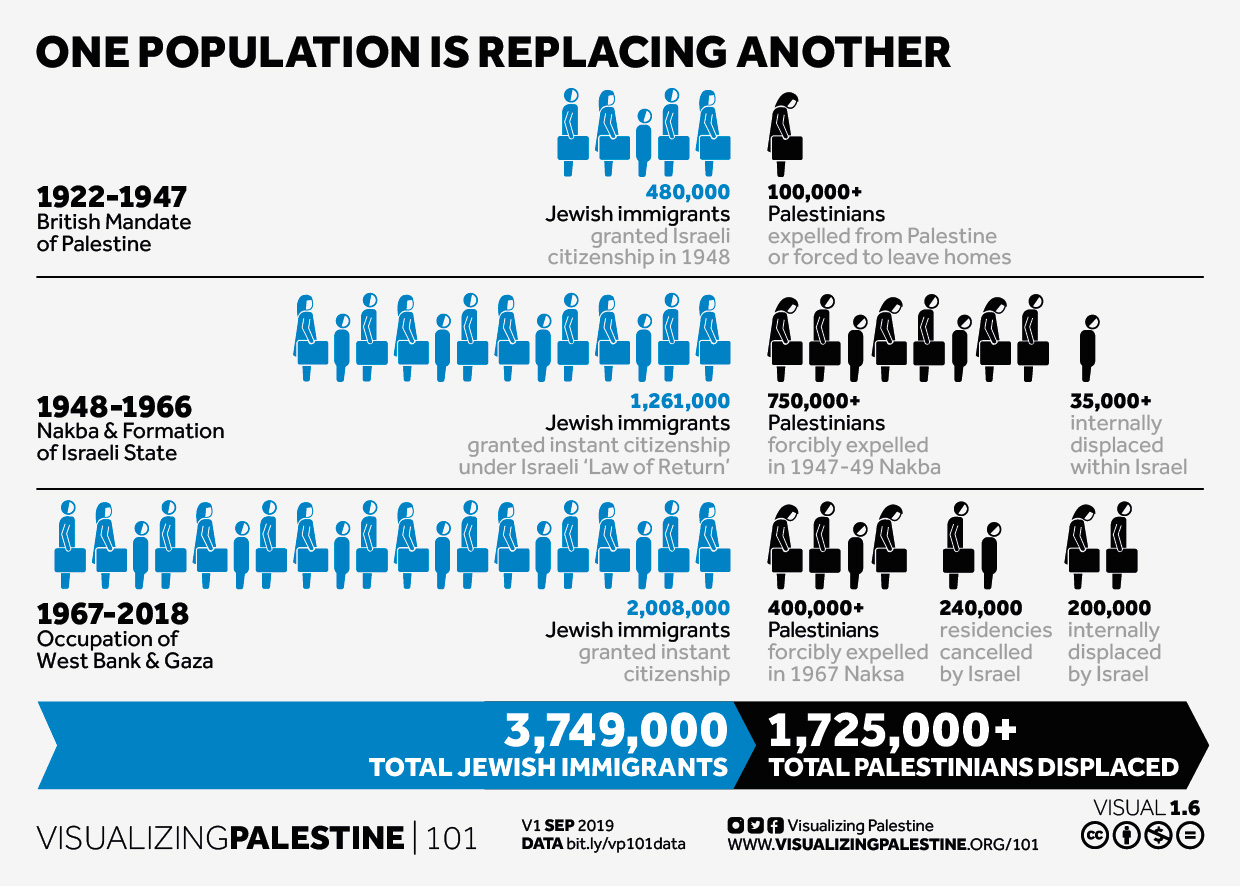

One population is replacing another. Visualizing Palestine. Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license

The Palestinian People Today

Some 750,000 Palestinians became refugees between 1947 and 1949. Their precise number and who bore the responsibility for their exodus are still disputed despite the abundant evidence that a majority fled or were driven out by Zionist/Israeli violence. One Zionist militia intelligence document estimates that as of June 1948 at least 75 percent of the Palestinians fled due to Zionist/Israeli military actions, psychological campaigns aimed at frightening Arabs into leaving and dozens of direct expulsions. The total proportion of expellees is likely higher since the largest single expulsion of the war—50,000 from Lydda and Ramle—occurred later, in mid-July.

There are several well-documented cases of massacres that led to large-scale Arab flight. The most infamous atrocity occurred in April 1948 (prior to the creation of Israel) at Deir Yassin, a village near Jerusalem, where about 110 Arab residents were massacred by right-wing Zionist militias, frightening as many as 50,000 Palestinians into fleeing from the area within days.

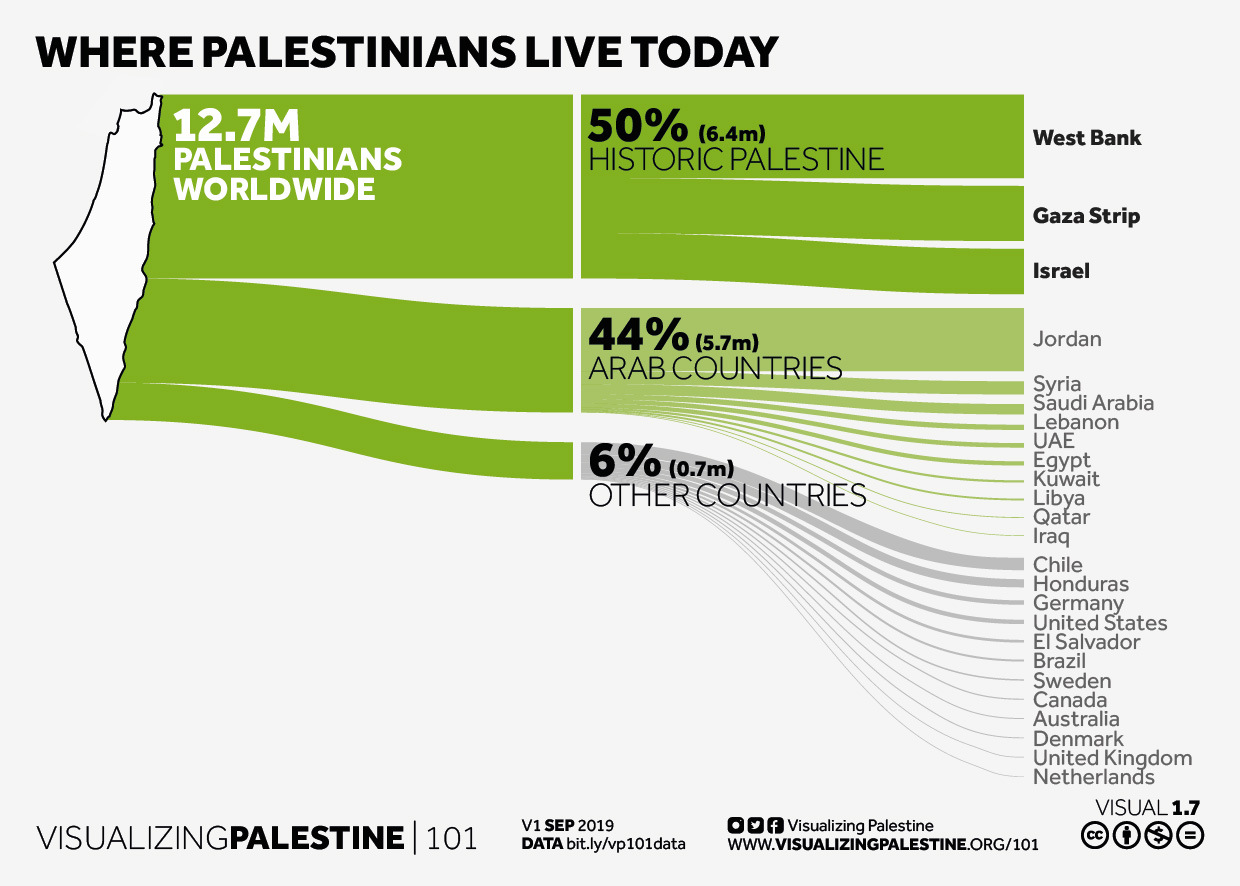

Today the global Palestinian population is 14–15 million. About 7 million live inside the borders of what was British Mandate Palestine. They include about 1.6 million citizens of Israel and 372,000 inhabitants of Israeli-annexed East Jerusalem, most of whom are permanent residents but not Israeli citizens. About 3 million Palestinians live in the West Bank and 2.2 million in the Gaza Strip (before October 7, 2023). An estimated 7 million live in diaspora outside the country they claim as their national homeland. (In addition, about 20 percent of the 24,000 Syrian Druze population in the Golan Heights, which Israel occupied in 1967 and annexed in 1981, have taken Israeli citizenship; the others are permanent residents with a status similar to Palestinians of East Jerusalem.)

The largest Palestinian diaspora community, approximately 3 million, is in Jordan. Many still live in the refugee camps that were established in 1949, although several camps have become urban neighborhoods. Lebanon and Syria also have large Palestinian populations, many of whom still live in refugee camps. About one-fifth of the half million Palestinians in Syria became refugees for a second time during the 2011 popular uprising and ensuing civil war; some were internally displaced inside Syria and others fled to Lebanon, Turkey and Europe. After 1948, many Palestinians seeking work moved to Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries. Others live elsewhere in the Middle East or further afield.

Jordan is the only Arab state to grant citizenship to its Palestinian residents. Syria grants Palestinian refugees most rights except citizenship. In other Arab states, Palestinians generally do not enjoy the same rights as citizens. The situation of the refugees in Lebanon is especially dire; many Lebanese blame Palestinians for provoking Israeli military assaults on the country as well as triggering the civil war that wracked Lebanon from 1975 to 1990 and demand that they be resettled elsewhere. Some elements of Lebanon’s Christian population are particularly anxious to rid the country of the mainly Muslim Palestinians because of their fear that Palestinians threaten the delicate sectarian system created in the French colonial period, in which Maronite Christians retain disproportionate political power.

Although many Palestinians still live precariously in refugee camps and urban slums, others have become economically successful. Palestinians have the highest per capita rate of university graduates in the Arab world. Their diaspora experiences and continued national disenfranchisement contributed to a high level of politicization and solidarity among all sectors of the Palestinian people. From the late 1960s through the 1990s, the great majority of Palestinians considered the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) as their political representative (see below). Many identified with one or another of its secular factions. In the 1980s, the regional Islamic revival led to the formation of Palestinian Islamist organizations (Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad) that opposed the PLO.

Where Palestinians live today. Visualizing Palestine. Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license

Palestinian Citizens of Israel

At the end of the 1948 War, approximately 156,000 Palestinians remained in the area that became the State of Israel. They were granted Israeli citizenship and the right to vote. But, because Israel defines itself as a Jewish state and the state of the Jewish people, in many respects Palestinian citizens—as non-Jews—were and remain second-class citizens. The Israeli government distinguishes between Muslim and Christian citizens, who it refers to as Israeli Arabs, and Druze citizens who it considers a separate minority group. There are also about 4,000 to 5,000 Circassian Israeli citizens.

Until 1966 Palestinian citizens were subject to a military government that restricted their movement and other rights (such as to work and political expression). They were not permitted to become full members of the Israeli trade union federation, the Histadrut, until 1965. At least 40 percent of their lands were confiscated by the state and used for development projects that benefited Jews primarily or exclusively. They were entirely isolated from the Arab world and often were regarded by other Arabs as traitors for living in Israel.

Every Israeli government has discriminated against its Palestinian citizens by allocating far fewer resources to their sector for education, health care, public works, municipal government and economic development. Starting in 1950 with the passage of the Law of Return, which grants any Jew who arrives in the country immediate citizenship, and the Law of Absentee Property, which enabled the state to expropriate lands owned by Palestinian refugees, dozens of laws entrench Palestinian citizens’ second-class status and reinforce structural inequality between Jews and non-Jews.

The Israeli state considers expressions of Palestinian or Arab national sentiment as subversive. For example, Palestinian citizens of Israel organized a general strike on March 30, 1976, which they designated as Land Day to protest the continuing confiscation of their lands. Israeli security forces killed six unarmed Palestinian citizens that day and injured more than 100 others. Palestinians have since commemorated Land Day as a national event.

In 2011, Israel passed the Nakba Law, which authorizes the Minister of Finance to withhold state funds from any government-funded body, such as a school or theater, that marks “Israel’s Independence Day … as a day of mourning” or that denies Israel’s character as a “Jewish and democratic state.” The 2018 Basic Law: Israel as the Nation-State of the Jewish People asserts: “The right to exercise national self-determination in the State of Israel is unique to the Jewish people” and declares Jewish settlement throughout the land a national priority. Israel’s Supreme Court has upheld many laws and policies that discriminate against Palestinian citizens.

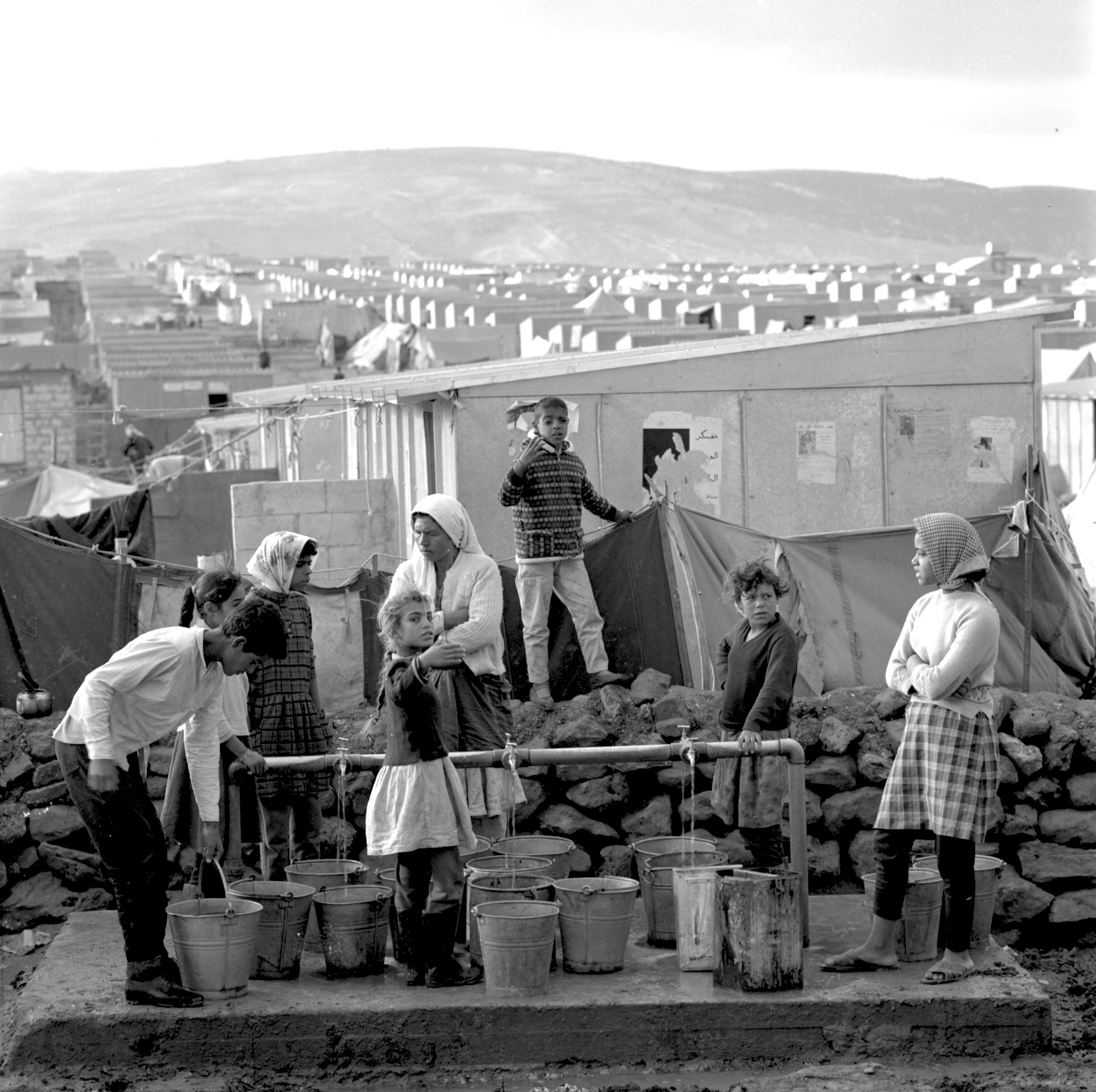

Palestinian refugee women and children fetch water in Irbid Camp, Jordan, 1969. Photographer unknown. UNRWA Archive

Israel and the Arab States

The 1948 War ended in 1949 with the signing of armistice agreements between Israel and Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria. Because Palestinians had no state, and as a people they were scattered throughout the various states of the region and beyond, the Palestinian-Zionist conflict was transposed to a conflict between Israel and its neighboring Arab states. In the 1950s, however, Palestinians outside of Israel began to reconstitute themselves as national actors, including through the formation of armed organizations intent on fighting for liberation. Fatah (a reverse Arabic acronym for Palestine Liberation Movement), which became the largest and most popular Palestinian armed organization, was formed by Palestinian refugees in Kuwait in 1959.

In the early 1950s, the Middle East was becoming a hot spot of Cold War rivalry as western states and the Soviet Union competed for regional power and influence. France became Israel’s major arms supplier and provided technological assistance to start its nuclear weapons program. The Soviet bloc was the main arms supplier for Egypt, Syria and, after the ouster of the monarchy in 1958, Iraq. Consequently, the region remained imperiled by the prospect of another war. The sense of crisis was fueled by a spiraling arms race as countries built up their militaries and prepared their forces (and their populations) for a future showdown.

In 1956, Israel joined with Britain and France to attack Egypt. The European powers sought to reverse Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s nationalization of the Suez Canal Company, a multinational corporation registered in France in which the British government held 44 percent of the shares. Israel had two additional aims: to neutralize Palestinian commando attacks on Israel from the Egyptian-administered Gaza Strip and to strike a blow against the Egyptian army before it could absorb arms it was set to receive as the result of a deal with Czechoslovakia the previous year. During the war, Israel conquered the Gaza Strip and the Sinai Peninsula and declared its intention to annex those territories. But Israel was forced to retreat to the 1949 armistice lines due to international pressure led by the United States and the Soviet Union (an uncharacteristic alignment during the Cold War era). UN troops then were placed on the Egyptian side of the Egypt-Israel border.

The June 1967 War

In May 1967, the Soviet Union misinformed the Syrian government that Israeli forces were massing in northern Israel to attack. There was no such Israeli mobilization. But clashes between Israel and Syria had been escalating for about a year, and Israeli leaders had publicly declared that it might be necessary to bring down the Syrian government if it failed to end Palestinian guerrilla attacks from Syrian territory, which Fatah (the militant organization led by Yasser Arafat) had started launching in 1965.

Egypt activated its defense treaty with Syria by sending troops into the Sinai Peninsula. A few days later, Egypt asked the UN observer forces stationed between Israel and Egypt to redeploy and proclaimed a blockade of the Gulf of Aqaba, arguing that access to the Israeli port of Eilat passed through Egyptian territorial waters, the Straits of Tiran. Nasser was playing a dangerous game of brinksmanship, hoping to benefit politically from a crisis but not desiring a war, especially since Egypt’s best military forces were occupied with fighting in Yemen during its civil war. These developments shocked and frightened the Israeli public who became worried that a multi-front war was imminent. In contrast to the public panic, Israel’s military high command was confident that it would prevail in a war with Egypt and Syria and urged the political leadership to authorize it.

On June 5, 1967, Israel preemptively attacked Egypt and Syria, destroying their air forces on the ground within a few hours. After Jordan joined in the fighting, Israel attacked it as well. The Egyptian, Syrian and Jordanian armies were decisively defeated within six days. Israel captured the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, from Jordan and the Gaza Strip and the Sinai Peninsula from Egypt. Israel also captured the Golan Heights from Syria and forcibly expelled 96 percent of the region’s population.

The June 1967 War established Israel as the dominant regional military power, with strong US backing. The speed and thoroughness of Israel’s victory discredited the rhetoric and supposed military readiness of the various Arab governments. Before the war, many Palestinians and other Arabs hoped that a united Arab world led by Egypt would confront Israel and liberate Palestine. After the war, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), which had been established by the Arab League in 1964 to manage Palestinian national activities, was taken over by Fatah and other militant political groups such as the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP, al-Jabha al-Dimuqratiyya li-Tahrir Filastin) and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP, al-Jabha al-Sha‘abiyya li-Tahrir Filastin). After 1967, the PLO emerged as a major regional actor, the principal representative of the Palestinian people and the embodiment of its aspirations for liberation.

UN Security Council Resolution 242

On November 22, 1967, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 242 affirming the “inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by force,” which would require Israeli withdrawal from all the lands it seized in the war and “acknowledgment of the sovereignty, territorial integrity and political independence of every State in the area and their right to live in peace within secure and recognized boundaries.” The grammatical construction of the French version of Resolution 242 says Israel should withdraw from “the territories” (les territoires), whereas the English version calls for withdrawal from “territories.” (Both English and French are official UN languages.) Israel and the United States use the English version to argue that Israeli withdrawal from some, but not all, territory occupied in the 1967 War would satisfy the requirements of this resolution. By calling for recognition of every state in the area, Resolution 242 affirmed Israel’s status as a recognized state without recognizing Palestinian national rights.

For many years the PLO rejected Resolution 242 because it frames the question of Palestine solely as a humanitarian issue and does not acknowledge Palestinian people’s right to national self-determination or to return to their homeland. It calls only for a “just settlement of the refugee problem,” without specifying what that phrase means.

The Occupied Territories

As a result of the 1967 War, the political map underwent a major transformation. From 1949 to 1967, the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, was ruled by Jordan, which annexed the area in 1950 and extended citizenship to Palestinians living there. In the same period, the Gaza Strip was under Egyptian military administration. After conquering these areas during the 1967 War, Israel established a military government to rule the Palestinian residents of the occupied West Bank and Gaza. The military government denied Palestinians basic political rights and civil liberties, including freedoms of expression, press and political association. Palestinian nationalism was criminalized as a threat to Israeli security, and displaying the Palestinian national colors was a punishable act. All aspects of Palestinian life were regulated and often severely restricted. Even something as innocuous as the gathering of wild thyme (za‘tar), a basic element of Palestinian cuisine, was outlawed by Israeli military orders. The State of Israel regards all forms of Palestinian opposition to the occupation as threats to its national security, including nonviolent methods like calling for boycotts, divestment and sanctions.

The Israeli army governs occupied Palestinians through policies of surveillance and punishment, relying on arrest, prosecution and imprisonment to control and deter Palestinian resistance to the occupation. The military administration uses collective punishments such as curfews, house demolitions and closure of roads, schools and community institutions. It has deported hundreds of Palestinian political activists to Jordan or Lebanon or transferred them from the West Bank to Gaza as well as confiscated tens of thousands of acres of Palestinian land and uprooted thousands of trees. In 1981 Israel established a Civil Administration to carry out the bureaucratic tasks of the occupation; it is subordinate to the military authorities.

At least 800,000 Palestinians have been incarcerated by Israel since 1967, many of them under administrative detention (imprisonment without trial). More than 40 percent of the Palestinian male population has been imprisoned at least once. Defense for Children International-Palestine calculated that since 2000, the Israeli military has detained some 13,000 Palestinian children, almost all boys between the ages of 12 and 17. Hundreds of them have been held without charges.

Israeli torture of Palestinian prisoners has been a common practice since at least 1971. Military judges rarely exclude statements elicited through interrogation that defense lawyers allege were coerced. Israeli officials have claimed that harsh measures and high rates of incarceration are necessary to thwart terrorism. Dozens of people have died in detention from abuse or neglect.

Israel argues that the Fourth Geneva Convention and other international laws governing military occupation of foreign territory do not apply to the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. It asserts that these territories are not occupied because they were never part of the sovereign territory of any state, as Jordan’s 1950 annexation of the West Bank was not widely recognized and Egypt never asserted sovereignty over Gaza. Officially, the Israeli government declares its role as the “administrator” of territory whose status remains to be determined. In contrast, Israeli religious and secular right-wing nationalists assert that the territories are an integral part of their historical heritage. The international community has rejected these Israeli positions. In July 2024 the International Court of Justice ruled that Israel’s governance and conduct in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip is illegal according to international law. But little effort has been mounted to enforce international law or hold Israel accountable for violations.

Every Israeli government has facilitated and subsidized Jewish settlement in East Jerusalem and throughout the West Bank in breach of the Fourth Geneva Convention. As a result, as much as 40 percent of the West Bank has been de facto annexed. Many settlements are built on expropriated, privately owned Palestinian lands. According to the Israeli NGO Peace Now, in 2024 there were 146 official Jewish settlements (legally acknowledged by the Israeli government) and about 191 unofficial settlement outposts and farms. In recent years Israel has been granting legal status to increasing numbers of those outposts. By 2023 there were 236,000 settlers in 12 East Jerusalem neighborhoods (settlements) and 478,600 settlers in the rest of the West Bank.

Critics of Israel’s occupation—Palestinians as well as international human rights NGOs like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International and Israeli NGOs like B’Tselem and Yesh Din—contend that Israel’s systematic discrimination and oppression of Palestinians constitutes apartheid. (Apartheid means apartness in Afrikaans, the language of Dutch settlers in South Africa, where this system and term were first institutionalized.) Human Rights Watch and Yesh Din contend that apartheid pertains to the OPT but not to the pre-1967 borders of Israel. Amnesty International and B’Tselem argue that apartheid prevails in all the territories governed by Israel because Israeli rule privileges Jews over Palestinians, from the river to the sea. The evidence of apartheid in the OPT includes the lack of legal rights for Palestinians, the system of separate identity cards and laws, military checkpoints, the exploitation of Palestinians as cheap labor, the massive expropriation of Palestinian land and water and exclusively Jewish settlements and separate roads for Israelis and Palestinians.

Jerusalem

The 1947 UN Partition Plan designated Jerusalem (and Bethlehem) as an internationally administered zone. In the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, Israel took control of the western part of Jerusalem, while Jordan took the eastern part, including the old walled city containing important Muslim, Christian and Jewish religious sites. The 1949 armistice line cut the city in two. In 1950, Israel declared (West) Jerusalem its capital.

On June 22, 1967, soon after capturing the West Bank (including East Jerusalem), Gaza Strip, Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights in the 1967 War, Israel expanded the municipal boundaries of East Jerusalem to include 70 square kilometers and 28 villages, most of which was never part of the city at any time in its history; this territory constitutes about 2 percent of the West Bank. Because of this annexation, most Palestinians living in East Jerusalem became residents of the State of Israel. Only a small number accepted Israeli citizenship.

Israel annexed East Jerusalem in 1980, proclaiming all of Jerusalem as its “eternal capital.” The UN Security Council responded with Resolution 476 (14-0 with the United States abstaining), which declared that “all legislative and administrative measures and actions taken by Israel, the occupying Power, which purport to alter the character and status of the Holy City of Jerusalem have no legal validity and constitute a flagrant violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention.”

In 1995, the US Congress—in a bipartisan show of support for Israeli unilateralism—legislated that the United States should recognize Jerusalem as Israel’s capital. Every subsequent president avoided implementing the law by certifying that US national security would be harmed by doing so. Disregarding this precedent, in December 2017, President Donald Trump recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital. Most of the international community continue to consider East Jerusalem part of the occupied West Bank. A new US embassy in Jerusalem was opened on May 15, 2018, on property situated between West Jerusalem and former no-man’s land between West and East Jerusalem—land Israel seized from the prominent Palestinian al-Khalidi family and a dozen other families.

The Palestine Liberation Organization

The Arab League established the PLO in 1964 to control Palestinian nationalism while appearing to champion the cause. The Arab defeat in the 1967 War enabled younger, more militant Palestinians to take over the PLO. In 1974, the Arab governments recognized the PLO as the sole legitimate representative of all Palestinians.

The PLO is comprised of groups that represent a range of ideological orientations and administer various sectors, including women’s associations, student unions and other civil society and social service organizations. It also has a military apparatus. Its leading bodies are the Palestinian National Council (PNC) and the PLO Executive Committee. PNC members were selected from among diaspora Palestinians according to a formula that reflected the relative size of the PLO’s constituent organizations. In their heyday, the armed factions of the PLO sought to wage an armed struggle to defeat Israel and liberate Palestine.

Yasser Arafat was PLO chairman from 1968 until his death in 2004. He also led Fatah, the largest party in the PLO. The other major groups are the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP) and, in the Occupied Territories, the Palestine People’s Party (formerly the Communist Party). Despite these factional differences, the majority of Palestinians regarded the PLO as their representative until it began to lose significance after the 1993 Oslo Accords and the establishment of the Palestinian Authority (PA) in 1994. The PNC has met only twice since the Oslo Accords, in 1996 and 2018. Hamas, an Islamist group established in 1987, is not a component of the PLO. The rise of Hamas, especially in the 2000s, further diminished the authority of the PLO (see below).

After the 1967 War, the PLO’s primary base of armed operations was Jordan. In 1970–1971, PLO armed factions fought and lost a civil war with the Jordanian army, which is known as Black September. The PLO leadership was compelled to leave the country and relocate to Lebanon. When the Lebanese civil war started in 1975, the PLO became a party to the conflict. After the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982, the PLO leadership was expelled from the country, relocating to Tunisia.

Until 1993, Israel did not acknowledge Palestinian national rights or recognize the Palestinians as an independent party to the conflict. Israel refused to negotiate with the PLO, arguing that it was nothing but a terrorist organization and insisted on dealing only with Jordan or other Arab states. It rejected the establishment of a Palestinian state, demanding that Palestinians be incorporated into the existing Arab states. Israel modified its opposition when its representatives entered into secret negotiations with the PLO, which led to the 1993 Oslo Declaration of Principles (see below).

The October 1973 War and the Role of Egypt

In 1971, Egyptian President Anwar al-Sadat indicated to UN envoy Gunnar Jarring that he was willing to sign a peace agreement with Israel in exchange for the return of the Egyptian Sinai Peninsula, occupied by Israel in the 1967 War. Israel and the United States ignored this overture. Egypt and Syria decided to break the political stalemate by attacking Israeli forces in the occupied Sinai and Golan Heights on the Jewish holy day of Yom Kippur, October 6, 1973.

The attack caught Israel off guard. The Arab militaries achieved some early victories, prompting US political intervention along with sharply increased military aid to Israel. The war ended with Israeli forces occupying a beachhead on the west bank of the Suez Canal, Egyptian forces with a beachhead on its east bank and Israeli forces occupying an additional swathe of Syrian territory. A diplomatic intervention was required.

US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger pursued a strategy of limited bilateral agreements to secure partial Israeli withdrawals from the Sinai Peninsula and the Golan Heights. Negotiations on the fate of the West Bank and Gaza could be avoided because Jordan had not participated in the war and Egypt did not seek the return of the Gaza Strip. Kissinger’s strategy positioned the United States as the sole mediator and most significant external actor in the conflict, a position it has sought to maintain ever since.

Israel was unwilling to negotiate for a full return of Egyptian territory, and Kissinger accepted this refusal. Sadat decided to initiate a separate overture to Israel. On November 19, 1977, he traveled to Jerusalem and addressed the Knesset, a powerful symbol of recognition that Israel hoped other Arab heads of state would emulate.

In September 1978, President Jimmy Carter invited Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin to the Camp David presidential retreat in Maryland. They negotiated two agreements: a framework for peace between Egypt and Israel and a general framework for resolution of the Middle East crisis—in other words, the Palestine question.

The first agreement formed the basis of the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty signed in 1979. The second agreement proposed to grant autonomy to the Palestinians in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip for a five-year interim period, after which the final status of the territories would be negotiated.

Only the Egyptian-Israeli part of the Camp David accords was implemented. The Palestinians and other Arab states rejected the autonomy concept because it did not guarantee full Israeli withdrawal from areas captured in 1967 or the establishment of an independent Palestinian state. Israel sabotaged negotiations by continuing to confiscate Palestinian lands in the West Bank and Gaza Strip and build new settlements in violation of the commitments Begin made to Carter at Camp David.

Palestinian children throw stones toward Israeli soldiers in the Amari refugee camp near Ramallah, in the West Bank, in February 1988 to protest against Israeli occupation. Eric Feferberg/AFP via Getty Images

The First Intifada

On December 9, 1987, the Palestinian population in the West Bank and Gaza began a mass uprising against the Israeli occupation. This uprising, or intifada (which means shaking off in Arabic), began in the Jabaliya refugee camp in Gaza after an Israeli truck hit a car and killed four Palestinians returning home from work. The uprising was not orchestrated by the PLO leadership in Tunis. Rather, it was a popular mobilization that drew on the organizations and institutions that had developed under Israeli occupation.

Hundreds of thousands of Palestinians participated in the Intifada, many with no previous resistance experience, including children and teenagers. For the first few years, the uprising involved many forms of nonviolent civil disobedience, including massive demonstrations, general strikes, refusal to pay taxes, boycotts of Israeli products, political graffiti and the establishment of underground “freedom schools.” (Israel closed regular schools as reprisals.) It also included stone throwing, Molotov cocktails and the erection of barricades to impede the movement of Israeli military forces.

Intifada activism was organized through popular committees under the umbrella of the United National Leadership of the Uprising. This broad-based resistance challenged the occupation as never before and drew unprecedented international attention to the situation facing Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza. Palestinian human rights organizations like Al-Haq, one of the first human rights organizations in the Arab world (established in 1979), prominently reported on Israeli violence and wide-scale violations of Palestinians’ human rights.

Israeli Defense Minister Yitzhak Rabin tried to smash the Intifada, ordering the military to use “force, power and beatings.” Army commanders instructed troops to break the bones of demonstrators, with the justification that broken arms cannot throw stones and broken legs cannot run away. From 1987 to 1991, Israeli forces killed over 1,000 Palestinians, including over 200 under the age of 16. Palestinian militants killed about 100 Israelis during this period as well as over 250 Palestinians suspected of collaborating with the occupation authorities. In 1988, Israel began a secret policy of extra-judicial execution (termed targeted killing) in the OPT. These operations are conducted by undercover units who disguise themselves as Arabs to approach and execute their targets at close range or by snipers who kill from a distance.

Israel also engaged in a massive arrest campaign in an attempt to crush the uprising. During this period, Israel had the highest per capita prison population in the world. By 1990, most of the Palestinian leaders of the uprising were in jail and the Intifada lost its cohesive force, although it continued for several more years.

Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad

In December 1987, in response to the First Intifada, Sheikh Ahmed Yassin formed Hamas (the Arabic acronym for Islamic Resistance Movement, Harakat al-Muqawama al-Islamiyya) a Palestinian Islamist group not affiliated with the PLO. Hamas grew out of the Gaza Strip branch of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood. In 1973 Sheikh Yassin established the Mujamma‘ al-Islami (Islamic Center) as a charitable and service association. In 1979 the Israeli military governor of Gaza recognized the group, thinking it posed no security threat and would draw support away from PLO factions. Hamas continued to provide social services to Palestinians while developing as a militia and political organization.

Palestinian Islamic Jihad (Harakat al-Jihad al-Islami fi Filastin) was established in 1981. Unlike Hamas, it argued that armed struggle to liberate Palestine should begin immediately, rather than waiting until Palestinian society was sufficiently Islamized to begin the struggle.

Hamas’s 1987 announcement of its creation and later statements released during the Intifada utilized a language of revenge for Israeli actions and policies and an anti-imperialism framed with Islamist justification. The August 1988 Hamas Charter includes standard antisemitic tropes. Hamas’s revised 2017 Document of General Principles and Policies eliminates that language, defines the conflict as “with the Zionist project, not with the Jews because of their religion” and declares that establishing “a fully sovereign and independent Palestinian state, with Jerusalem as its capital along the lines of the 4th of June 1967, with the return of the refugees and the displaced to their homes from which they were expelled” is “a formula of national consensus.”

The rise of Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad challenged the authority of the PLO. Political divisions and violence within the Palestinian community escalated during the First Intifada, driven by the growing rivalry between the various secular PLO factions and the Islamist organizations.

Palestinian Declaration of Independence and Recognition of Israel

The Intifada made clear that the status quo was untenable. The center of gravity of Palestinian national and political initiatives shifted from the PLO leadership in Tunis to the OPT. Palestinian activists in the OPT demanded that the PLO adopt a clear political program to guide the struggle for independence. In response, the PNC convened in Algeria in November 1988. It renounced terrorism and proclaimed an independent Palestinian state in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, thereby implicitly recognizing the State of Israel.

The Israeli government did not respond to these gestures, claiming that nothing had changed and that the PLO remained a terrorist organization with which it would never negotiate. The United States did acknowledge that the PLO’s policies had changed but did not exert pressure on Israel to follow suit.

Because of US and Israeli failure to respond meaningfully to PLO moderation, the PLO opposed the 1991 US-led attack on Iraq after the regime of Saddam Hussein invaded and occupied Kuwait. Kuwait and Saudi Arabia cut off financial support to the PLO and expelled hundreds of thousands of Palestinians who had been living and working in those countries. After the 1991 Gulf War, the PLO was diplomatically isolated.

The 1991–1992 Negotiation Process

In return for Arab states’ support of the 1991 US-led Gulf War against Iraq, the administration of President George H. W. Bush pressed Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir to open negotiations with Palestinians and the Arab states at a multilateral conference convened in Madrid, Spain, in October 1991. Shamir, a former leader of the militant right-wing pre-state group LEHI, was reluctant to negotiate and imposed conditions, which the US accepted: exclusion of the PLO from the talks, Palestinian representation only as part of the Jordanian delegation and no discussion of Palestinian independence and statehood.

The Madrid conference was largely ceremonial. At subsequent negotiating sessions in Washington, Palestinians were represented by a delegation from the OPT and diaspora Palestinians. However, Israel barred residents of East Jerusalem from participating on the grounds that the city is part of Israel (by virtue of annexation). Although the PLO was formally excluded, its leaders regularly advised and consulted with the Palestinian delegation. These negotiations achieved little progress. After leaving office in 1992, Shamir acknowledged, “I would have carried on autonomy talks for ten years and meanwhile we would have reached half a million people [settlers] in Judea and Samaria [the official Israeli name for the West Bank].”

After Yitzhak Rabin succeeded Shamir as prime minister, human rights and economic conditions in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip deteriorated dramatically, and Israeli land confiscation and settlement building escalated. Several Palestinian delegates to the Washington talks resigned in protest.

As the negotiations floundered, the popularity of Islamists grew and challenged the diplomatic strategy of the PLO. Violent attacks against Israeli military and civilian targets by Hamas and Islamic Jihad further exacerbated tensions. Eventually Rabin came to believe that Hamas and Islamic Jihad posed more of a threat to Israel than the PLO.

The Oslo Accords and the Palestinian Authority

Israeli fear of “radical Islam” and the insistence of the Palestinian delegates to put self-determination and statehood on the table at the Washington talks led the Rabin government to reverse Israel’s long-standing refusal to negotiate with the PLO. Israel initiated a secret track of negotiations directly with PLO representatives in Oslo, Norway. These talks produced the Israel-PLO Declaration of Principles (DOP), which was signed in Washington in September 1993 by Rabin and Arafat and witnessed by President Bill Clinton whose administration was not involved in its negotiation.

The DOP stipulated mutual recognition of Israel and the PLO. Israel committed to withdrawing from the Gaza Strip and Jericho and to additional unspecified areas of the West Bank during a five-year interim period. The document does not mention a Palestinian state or the right of Palestinian self-determination, which Israel continued to oppose. The key issues—the extent of the territories to be ceded by Israel, the nature of the Palestinian entity to be established, the future of Israeli settlements and settlers, water rights, the resolution of the refugee problem and the status of Jerusalem—were to be discussed only in “final status” talks. The PLO accepted this deeply flawed agreement because it was weak and had little diplomatic support in the Arab world. Islamists and some leaders of PLO factions other than Fatah challenged Arafat’s leadership and rejected the negotiated concessions. The Palestinian poet laureate Mahmoud Darwish, who had authored the Palestinian Declaration of Independence in 1988, resigned from the PLO Executive Committee, and Edward Said, who had translated the declaration into English, did likewise from the PNC.

Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad also opposed the Oslo Accords and began armed resistance to thwart them. Hamas carried out the first suicide bombing inside Israel in April 1994 in response to Israeli settler Baruch Goldstein’s massacre of worshippers in the al-Haram al-Ibrahimi Mosque in Hebron on February 25, 1994.

In 1994, in partial fulfillment of the DOP, the PLO formed a Palestinian Authority (PA) with limited self-governing powers in occupied areas from which Israeli forces were redeployed. In January 1996, elections were held for the Palestinian Legislative Council and for the presidency of the PA, which were won by Fatah and Arafat, respectively.

The Oslo Accords set up a negotiating process without specifying an outcome. The process was supposed to be completed by May 1999. During the protracted interim period, Israel dramatically escalated settlement building and land confiscations in the OPT and constructed a network of bypass roads to enable Jewish settlers to travel from their settlements to Israel without passing through Palestinian-inhabited areas. These projects were widely understood as marking out territory Israel sought to annex in the final status agreement. Although the Oslo accords barred both parties from changing the status quo on the ground in these ways, it contained no mechanism to block Israel’s unilateral actions or violations of Palestinian human and civil rights. Settlers also undermined the negotiated agreements, escalating their attacks and flexing their electoral strength to bring more anti-Oslo politicians into office.

The Oslo process divided the OPT into three categories. In Palestinian cities and towns in the West Bank that Israeli forces had vacated—designated Area A—the PA was in charge of internal security and municipal services. In other Palestinian towns and villages—designated Area B—the PA and the Israeli military were jointly responsible for internal security. In all other areas including Jewish settlements and the Jordan Valley—designated Area C—Israel maintained exclusive control. A similar division was imposed on the Gaza Strip. By 2000, the PA only held direct or partial control over approximately 40 percent of the West Bank and 65 percent of the Gaza Strip. Areas A and B were fragmented and surrounded by Area C with checkpoints to control and restrict Palestinians’ entry and exit.

In July 2000, Clinton invited Arafat (as PA president) and Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak to Camp David to conclude negotiations on the overdue final status agreement. Before they met, Barak proclaimed his red lines: Israel would not return to its pre-1967 borders, East Jerusalem would remain under permanent Israeli sovereignty, Israel would annex settlement blocs in the West Bank containing some 80 percent of the 190,000 (now about 478,600) Jewish settlers and Israel would not accept legal or moral responsibility for creating the Palestinian refugee problem. The Palestinians, in accordance with their understanding of UN Security Council Resolution 242 and the spirit (but not the letter) of the Oslo DOP, sought Israeli withdrawal from the vast majority of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, including East Jerusalem, and recognition of an independent Palestinian state in those territories.

The distance between the two parties, especially on the issues of East Jerusalem and refugees, made it impossible to reach an agreement at Camp David. Although Barak offered Israeli withdrawal from more of the West Bank than any other Israeli leader had publicly considered, he insisted that an agreement must include Israeli control of the Jordan Valley and exclusive Israeli sovereignty in East Jerusalem.

When the negotiations collapsed, Arafat left Camp David with enhanced stature among his constituents because he did not yield to US and Israeli pressure. Barak returned home to face a political crisis. Even before departing for Camp David, he had lost his Knesset majority when coalition partners quit his government on the grounds that he was willing to offer the Palestinians too much.

The Second (al-Aqsa) Intifada

The inherent flaws in the so-called peace process initiated at Oslo, combined with the daily frustrations and humiliations inflicted upon Palestinians, continuing Israeli settlement in the OPT and corruption in the Palestinian Authority, set the stage for a second intifada. Like the First Intifada, the Second Intifada (also called al-Aqsa Intifada) was a protest against Israeli occupation. On September 28, 2000, Ariel Sharon, a hardline opponent of any Israeli territorial withdrawal who was challenging Benjamin Netanyahu for leadership of the Likud party in upcoming elections, went to Jerusalem’s Temple Mount/Noble Sanctuary accompanied by 1,000 armed guards. This aggressive spectacle provoked large Palestinian protests. The following day, Palestinians threw rocks at Jews praying at the Western Wall. Israeli police then stormed the Temple Mount and killed at least four and wounded 200 unarmed protesters. By the end of the day Israeli forces had killed three more Palestinians in Jerusalem.

These killings prompted demonstrations and clashes across the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. In October there were widespread solidarity demonstrations and a general strike by Palestinian Arab citizens of Israel. Police killed 12 unarmed Palestinian citizens of Israel and one West Bank resident.

The Second Intifada was much bloodier than the first. During the first three weeks, Israeli forces shot 1 million live bullets at Palestinian demonstrators. The Israeli military escalated its use of force to avert a protracted civil uprising like the First Intifada, which had garnered international sympathy for Palestinians. On some occasions, PA police, usually positioned at the rear of unarmed demonstrators, returned fire.

Israel expanded its armed violence against the protests, deploying tanks, helicopter gunships and even F-16 fighter planes. The Israeli army attacked PA offices in Ramallah, Gaza and elsewhere. Civilian neighborhoods were subjected to shelling and aerial bombardment. In November 2000, Israel acknowledged for the first time its policy of targeted killing after a suspected Palestinian militant was assassinated by a missile strike along with two women bystanders.

Israeli officials justified waging full-scale war on Palestinians in the OPT by arguing that the law enforcement model (policing and riot control) was no longer viable because Israel’s military had withdrawn from Area A and because Palestinians possessed (small) arms and thus constituted a foreign “armed adversary.” They described the Second Intifada as an “armed conflict short of war” and claimed that Israel had the right of self-defense against an “enemy entity,” while denying that those stateless enemies had any right to use force, even in self-defense. Israeli forces killed at least 3,000 Palestinians during the Second Intifada. Israel likened its unprecedented use of force against occupied Palestinians to the US War on Terror, launched in 2001 after the September 11 terrorist attacks, and compared Palestinian militants to al-Qaeda.

Hamas and Islamic Jihad, and later some units of the PFLP and the Fatah-affiliated al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade, retaliated with suicide bombings and other armed operations. There were over 150 such attacks between 2000 and 2005, which killed as many as 1,000 Israelis, compared to the 22 suicide attacks from 1993 to 1999 by opponents of the Oslo process.

In January 2001, direct Palestinian-Israeli negotiations resumed briefly at Taba (in the Sinai), with no US presence. The lead negotiators claimed that they came “painfully close” to a final agreement before talks were called off by Barak in advance of the early elections that he had called because he no longer had a majority in the Knesset. With intense support from settlers and those Israelis who viewed the peace process as threatening their security, Ariel Sharon handily defeated Barak in the February 6 election.

Sharon’s first term as prime minister coincided with the most violent period of the Second Intifada. On March 27, 2002, a suicide bombing in Netanya during the Passover holiday killed 30 Israelis and injured 140. In retaliation, Israel launched Operation Defensive Shield, a full-scale invasion of the West Bank that lasted for several weeks and was Israel’s largest military operation since the 1982 invasion of Lebanon. It signaled Israel’s willingness to inflict more intensely punishing levels of violence and destruction with the aim of debilitating Palestinian capacities, deterring future attacks against Israel and targeting not only militants but the broader Palestinian society.

During Operation Defensive Shield, Israeli forces re-entered many parts of Area A and laid waste to the infrastructures of the PA. The Battle of Jenin Refugee Camp was the emblematic confrontation of the campaign. While many refugee camp residents fled before the fighting began on April 2, Palestinian fighters from several factions prepared for the Israeli army’s incursion and killed 13 Israeli soldiers in an ambush on April 9. This incident generated intense political pressure within Israel to take the camp quickly with minimal military casualties. Consequently, instead of sending soldiers into buildings to capture or kill fighters, the army shelled some buildings first and commandeered Palestinian civilians as human shields to precede and protect soldiers. To finish the Jenin operation, the military deployed armored bulldozers that flattened everything in their path. Human Rights Watch documented 52 Palestinians killed in the Jenin refugee camp and concluded that Israeli forces committed war crimes and other serious violations of international humanitarian law.

On July 22, 2002, an Israeli F-16 dropped a one-ton bomb on the densely populated Gaza City neighborhood of al-Daraj in order to assassinate Hamas military commander Salah Shehadeh. The bomb destroyed Shehadeh’s apartment building and eight nearby buildings, partially destroying nine others. In addition to Shehadeh and his guard, the bombing killed 14 Palestinians, including eight children, and injured more than 150 people. The Israeli military responded to public outcry about the size of the bomb, the targeting of a residential neighborhood and the high number of casualties with an investigation. It concluded that there had been “shortcomings in the information available,” namely the presence of “innocent civilians” in the vicinity of what was claimed to be Shehadeh’s “operational hideout.” Although Moshe Ya‘alon, Israel’s chief of staff at the time of the bombing, cancelled a trip to Britain in 2009 because he feared an arrest on war crimes charges, no one was ever held accountable.

Ascendancy of the Israeli Right Wing

The Likud and parties to its right have dominated Israeli politics in the twenty-first century. The Likud is the direct heir to the Revisionist Zionist ideology of territorial maximalism and aggressive deployment of indiscriminate armed force to suppress Palestinian resistance to the Zionist project. Right wing religious Zionism is rooted in the theology of Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, the first Ashkenazi chief rabbi of Mandate Palestine. He rejected the 1947 UN Partition Plan and taught that settling the Land of Israel (on both banks of the Jordan River) is the most important of the 613 commandments in the Torah. Messianist religious Zionists believe that Israeli control of East Jerusalem heralds the coming of the Messianic Era. Some believe that constructing a third Temple to replace the Muslim structures on the Noble Sanctuary/Temple Mount would hasten the coming of the Messiah. The only substantial peace talks that took place in this political environment were in 2007–2008, when Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas and Sharon’s successor, Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert, came close to agreeing on a peace deal. Talks broke down when Olmert announced his resignation in advance of his incarceration on corruption charges.

The ascendancy of the Israeli right marked the end of the Oslo peace process since the Likud and all the parties of the right unequivocally opposed establishing a Palestinian state or making any so-called territorial concessions whatsoever. Many Palestinians also came to reject the limitations of the Oslo process for failing to come close to delivering peace or a Palestinian state. Today, the term “peace process” is most often used as a pro forma endorsement of the increasingly unlikely two-state solution.

Palestinians pass through the checkpoint separating Bethlehem and Jerusalem, to attend the last Friday prayers of holy month of Ramadan at the Al-Aqsa Mosque, 2023. Wisam Hashlamoun/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

The Separation Barrier

In 2002 the Israeli government authorized the construction of a barrier to separate Israel and Jewish settlements close to the Green Line (marking the pre-1967 border) from other parts of the West Bank. Sharon initially opposed such a separation because he sought to annex the entire West Bank. But the combination of security pressures and the realization that full annexation would make it demographically impossible for Israel to remain a majority Jewish state led him to approve the barrier.

The separation barrier is built on confiscated Palestinian lands and runs mostly to the east of the Green Line. About 95 percent of the barrier consists of an elaborate system of electronic fences, patrol roads and observation towers constructed on a path as much as 300 meters wide. About 5 percent, mostly around Qalqilya and Jerusalem, consists of an 8-meter-high concrete wall. The area between the Green Line and the barrier—about 9.5 percent of the West Bank—is known as the “seam zone” and has been a closed military area since 2003; it is functionally detached from the West Bank and de facto annexed to Israel.

Israeli officials call the barrier a “security fence” to highlight their argument that it is essential for Israeli security. Palestinians refer to it as the “apartheid wall” because it isolates and encloses them in areas that resemble the Black Bantustans in apartheid South Africa. The barrier divides Palestinian communities, blocks routes of travel even within towns and villages and reconfigures the geography of the West Bank.

In 2004, Palestinians submitted a request to the International Court of Justice for an advisory opinion on the legality of the barrier. In a 14 to one vote, with the US justice dissenting, the ICJ ruled that “the construction of the wall, and its associated régime, are contrary to international law.”

Israel’s Withdrawal from the Gaza Strip

In early 2004 Sharon announced his intention to unilaterally withdraw Israeli forces from the Gaza Strip. The objective was to relinquish direct control of an impoverished and densely populated territory in order to concentrate Israeli territorial ambitions more squarely on the West Bank and to ease diplomatic pressures on Israel to negotiate for a Palestinian state.

To accomplish this withdrawal from Gaza in the face of opposition within his Likud party, Sharon formed a new party, Kadima (Forward), with defectors from the Likud and Labor parties in 2005. In August and September of that year, the Israeli military was redeployed out of the Gaza Strip, all Jewish settlements were evacuated and demolished and the Strip was sealed by a wall adhering closely to the Green Line.