There has been no satisfactory resolution of these tensions and other core issues that led to the decades-long conflict. Grievances concerning the status of stateless Palestinians in Lebanon as well as the rights and representation of certain religious communities within the framework of the Lebanese sectarian nation-state remain unaddressed. Some argue that the civil war has still not truly ended. Over the course of the 1990s and 2000s, though, new expressions of popular culture served as spaces through which individuals and the society more broadly could reckon with some of its causes and consequences. While there is no consensus account of the Lebanese civil war taught in state textbooks, for example, it is commonly discussed in the press, in everyday discourse and in public culture more broadly. If the war was once referred to in sanitized terms, such as “the events” (al-ahdath), it is far from uncommon now to hear mention of “the civil war” (al-harb al-ahliyya).

In the late twentieth and early twenty-first century, film became an important site for the investigation of memories and injuries of the war and its afterlives. The celebrated and cherished films of Maroun Baghdadi, for example, offered a celluloid window onto social and cultural life in the context of the civil war. The dreamy cinematic meditations of Mai Masri and Danielle Arbid identified the collision between desire and destruction in the maelstrom of the war as well as the incomplete manner in which the country reckoned with its aftermath.

Ziad Doueiri is perhaps the most widely recognized filmmaker of the Lebanese civil war. His first film, West Beirut (1998), was a nostalgic look at sectarian difference amid the outbreak of war told through the lens of childhood, friendship and young love. His two subsequent films, Lila Says (2004) and The Attack (2012) were set in France and Israel/Palestine, respectively. The Attack, based on a novel by Algerian writer Yasmina Khadra about a Palestinian suicide bomber, set off a firestorm of criticism across the Arab world when it was revealed that Doueiri had traveled to Israel to shoot the film. For that reason, the Lebanese government, the Egyptian government, Palestinian civil society organizations and others called for a boycott of the film, accusing Doueiri of “normalization” of the Israeli occupation through his collaboration with Israeli institutions and visit to occupied Palestine. In September 2017, upon returning to Lebanon from a film festival in Europe, Doueiri was detained by state security for violating Lebanese law barring visits to Israel, and the status of the film in Lebanon remains precarious. In October, a screening of the film in Ramallah was cancelled because the film and the filmmaker were seen as contributing to normalization.

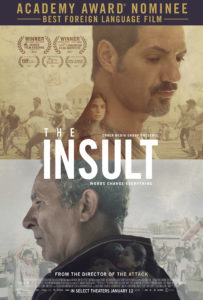

His most recent film, The Insult (Qadiya Raqam 23 or Case Number 23), which was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Picture (but eventually lost out to the Chilean film A Fantastic Woman), returns to the topic of the Lebanese civil war in order to meditate on the state of Lebanese society, politics and memory today and the status of the civil war in public culture and collective memory. The Insult is disarmingly direct in its engagement with the problem of sectarianism, civil conflict and the Arab-Israeli conflict, tackling these issues in a manner that would have seemed unimaginable even 20 years ago. The film raises legal, ethical and political questions about the state of Lebanese cultural production. In Arabic, the title Case Number 23 is more banal, less explosive, than the English and French title, The Insult/L’Insulte. The simple title masks a much more complex narrative film that cuts to the heart of ongoing debates within Lebanese cultural politics and political culture.

Insult and Injury

Tony Hanna (played by Adel Karam) is a hard-working family man who owns a car repair shop in Fassouh, a working-class Christian neighborhood in East Beirut. He and his wife Shirine (Rita Hayek) are expecting their first child. Shirine has grown tired of the stress of urban life and constantly tells Tony they should move back to Damour, his ancestral village along the Mediterranean coast just south of Beirut. He is also an ardent supporter of the Lebanese Forces, a right-wing political party and former Christian militia, which the English-language subtitles refer to as “the Christian Party.” He publicly displays his loyalty to “the martyr” Bashir Gemayel, the founder, and unstinting support for “the doctor” Samir Geagea, the current party president.

Tony’s life is turned upside down by a seemingly unremarkable incident, when a leaky drainpipe spills water on construction workers and engineers who are working in the area. One of the foremen, Yasser Salameh (Kamel El Basha), who also happens to be a Palestinian from the Mar Elias refugee camp, and who is 15 years Tony’s senior, takes his own initiative to repair the leak from Tony’s balcony. When Tony discovers what Yasser and his men have done, he takes a hammer and smashes the work. At this point, Yasser calls Tony a “prick,” according to the English-language subtitles, though the term used in Arabic means pimp. (Doueiri has indicated in interviews that the germ of the film was a similar run-in he himself had in Beirut.)

At this point, Yasser’s boss Talal tells him that he needs to apologize. Tony has demanded an apology or he will not let the construction crew work in peace. Yasser’s wife Manal (Christine Choueiri) convinces him this is the right thing to do. When Yasser shows up at Tony’s garage, a video of Bashir Gemayel attacking the Palestinians as a rootless and worthless people blares in the background. Tony loses his patience and echoes Bashir Gemayel when he tells Yasser the Palestinians are a “rootless people,” parroting the Zionist adage that Palestinians never miss an opportunity to miss an opportunity, and then saying the Jews were right to force them out of the country. “I wish Ariel Sharon had wiped you all out,” he snarls. At this point Yasser punches Tony in the stomach. Tony is taken to the hospital with two broken ribs.

From here the plot takes some predictable but no less dramatic turns. Tony sues Yasser, infuriated that the police cannot do anything because they do not have jurisdiction in the Palestinian refugee camps. When Yasser turns himself in, the two men wind up before the court of first instance, neither of them with legal representation. The presiding judge asks about the specific insult that led Yasser to strike Tony but neither man will say. The judge shames Tony for his own violation of the law (his leaky pipe) and throws out the case. Tony goes ballistic (“If only I were a Palestinian!”). There is a brief cold peace, until one evening Tony pulls a muscle trying to pick up a heavy battery, at which point he and Shirine wind up in the hospital where their child is born prematurely and placed in the neonatal intensive care unit.

Enter the white-shoe lawyer Wajdi Wehbeh (Camille Salameh), slick and polished, who takes the case on a pro bono basis. Wehbeh is famous for his involvement in other high-profile cases, including a failed defense of the leader of “the Christian Party.” The woman hired to defend Yasser (Diamand Bou Abboud) is an idealistic young lawyer whom we meet as she steps out of her stylish Mini Cooper in high heels and strides into the Mar Elias refugee camp to visit Yasser and his wife Manal. The viewer later learns that the defense lawyer is none other than Nadine Wehbeh, daughter of Wajdi, introducing a thread of family rivalry and generational conflict to the story.

The trial that follows becomes a meditation on the politics and legacies of the civil war, of the relationship between verbal injury and physical assault, on the possibility of reconciliation through individual apology, forgiveness, retributive justice and truly “turning the page.” Part courtroom drama, part historical education, the film turns into a morality tale about the Lebanese civil war, the status of Palestinians in Lebanon and the question of injury and speech and the limits of retributive justice.

One remarkable aspect of this melodramatic show trial is the introduction of historical and visual evidence into the courtroom. When video of Bashir Gemayel’s hateful speech about Palestinians in Lebanon and around the region is played, Wajdi responds in protest, claiming those words are just words. “We are in the Middle East,” where the term “enmity” was coined, he says, eliciting a chuckle from the crowd. Wajdi makes other incendiary claims about the region, including the strange argument that if Tony had not invoked Ariel Sharon killing Palestinians but rather raised the Eskimos or the Smurfs doing so, they never would have wound up in court. “When a Jew kills an Arab it’s a problem,” Wajdi provocatively argues, “but Arabs killing Arabs is not a problem.”

Inevitable Sectarians?

As the case heats up, it acquires national and then international significance. The president of the republic invites Tony and Yasser to the presidential palace in Baabda, where he beseeches them to end their dispute for the good of the country. Tony aggressively challenges the president, telling him that he is a public servant, asking whether he believes the Palestinians in Lebanon are “God’s chosen people.” The president retorts, “Do you want to start a war?” The question implicit here, of course, is whether the war ever ended, in the minds of Tony Hanna and Wajdi Wehbeh, in the minds of Yasser and his wife, in the mind of Ziad Doueiri himself, to say nothing of the audience.

In one of the film’s most poignant scenes, Yasser’s car will not start as they are both leaving, and Tony casually helps him get it running. Despite the good feeling created in this moment of humane and even tender care, a question arises that uncomfortably stalks the entire film: are these two men—is the country—capable of reconciliation or tolerance? And, even more difficult: is the liberal principle of tolerance embedded in this gesture—and the melodramatic music that attends it—all that Ziad Doueiri has to offer? Can tolerance take the place of an adequate accounting of the horrors of the Lebanese civil war and stand in for the work of mourning that would be required to “turn the page” on “the events,” as Lebanese politicians say so often? When the leader of “the Christian Party”—a surrogate figure for Samir Geagea—appears on screen in a fictional episode of the actual television program “Objectively Speaking” (“Bi-mawdu‘iyyah”) in order to bemoan the fact that the country “never had a real national reconciliation,” he addresses Tony directly on camera: “I know what happened to you. We can’t change the past.” Nevertheless, the political leader goes on to admonish Tony that he—that the Lebanese people—must recognize that “the war is over.” The notion that one of the most unrepentant militia leaders in the history of the Lebanese civil war, one who has been reintegrated into the political system by way of the amnesty law that pardoned all warlords and political bosses who were largely responsible for the intractable fighting, would arise as the voice of reason in this moment strains credulity.

When Tony takes the stand in court, Wajdi blindsides him by introducing video footage from the massacre at Damour. Fighters from the left-wing Lebanese National Movement (LNM) and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) besiege the village and clash with the local Christian militiamen as their leadership tries to evacuate women, children and families: some are taken to Kaslik, others elsewhere; some attempt to go by sea while others run along the nearby train tracks. With archival video and visual imagery present in the courtroom, it would seem that the Lebanese civil war itself is now on trial. Tony glances backwards to see his father doubled over in pain, in tears, at which point he switches off the video and storms out of the courtroom with his father in tow. In a sense, Wajdi has introduced the problem—without using the term—of what might be called comparative victimology, that is, an attempt to quantify relative suffering and then to litigate physical, emotional and psychological damages.

Sitting alone back home in his garage one night, Tony emerges to find Yasser out in the street, asking how many of his ribs he had broken, provoking him, telling Tony that he talks too much, that all of his problems had befallen him because he did not know how to keep his big mouth shut. Yasser taunts him mercilessly: “you think you’re a victim”; “victim, my ass”; “you all were tourists during the war—hanging out in Switzerland and shopping”; “you are spoiled brats” who don’t know the meaning of suffering. He continues until Tony punches Yasser in the stomach. It is only then that Yasser mutters, “I’m sorry.”

In his closing argument, Wajdi says, “No one has a monopoly on suffering.” Be that as it may, the presiding Judge Colette Mansur returns the verdict: a two to one vote declaring Yasser Salameh not guilty. As Tony and Shirine are about to be taken away by a police escort, he looks back up at Yasser atop the courthouse steps, smiling slightly as Yasser stands there with a wistful smirk on his face. In the final shot, a rearward view of Beirut expands to fill the screen as the camera takes the audience up, up and away from the scrum of daily life. The helicopter-shot view of Beirut zooms us out of the city and away from a place that seems unchanged, condemned to an eternal and cyclical fate.

Although this ought to be a punctuating moment in the film, the climax of a taut narrative, what anyone is actually feeling in this moment, as they all shake hands and hug and walk away, remains hard to describe. Indeed, it is unclear what any of this is taken to mean altogether. What does Wajdi think about the fact that his daughter Nadine has won her first case against him as they sit uncomfortably side by side in their counselor’s chairs, the prodigal daughter having defeated her larger-than-life father for the first time? There is little sense of whether they have learned something about each other, about their own (Christian) family history or about the role of the law in the adjudication of Lebanese history. In other words: What was this all for? What are the consequences of this defeat for his political project and that of “the Christian party”? What are Tony and Shirine thinking as they drive off under police escort? What are Yasser and Manal feeling as they head back to the Mar Elias camp? What will be the fate of other Palestinians in Lebanon who are still unable to legally work in most sectors of the Lebanese economy? What will Yasser, in particular, do now that he has been fired from the job he had been on when this whole mess started? The expectation would seem to be that everyone will quietly, however repentantly, return to the status quo ante.

The Law of No Victor, No Vanquished

While some critics mock the film’s melodramatic predictability—“a diverting, junky courtroom drama” according to one critic [1]—The Insult has been widely acclaimed for its forthright consideration of controversial issues in the Lebanese and Palestinian contexts. The Academy of Arts and Motion Pictures saw fit to recommend the film as the first from Lebanon to be on the short list of nominees for Best Foreign Picture. But there are complex ideological dimensions to the varied reception of the film in the US and Europe, on the one hand, and its reception in the Arab world, on the other, that need to be taken into account.

There is a problem embedded in the narrative of the film regarding the relationship between sectarianism and violence. After the court of first instance rejects Tony’s claim against Yasser, Tony’s father, a survivor of the Damour massacre, chides his son for being so sore about the whole thing. “That’s how wars start…you were in the wrong,” he says. But historians and other analysts of the Lebanese civil war should be forgiven for responding by asking whether this is indeed how wars start, whether a war such as the Lebanese civil war starts because of individual insults or because of a political system that institutionalizes sectarianism. The Arab-Israeli conflict, which created the Palestinian refugee community that wound up in Lebanon in 1948, 1967 and 1970, increased the hostility of the Lebanese Forces and is one of the leading reasons why the wars in Lebanon broke out. These thorny issues are skated over as the politics of sectarianism and civil conflict in Lebanon are reduced to personal differences.

Masculinity also plays a key role in this regard. The verbal insult Yasser hurls at Tony may have kicked off the conflict, but it is the physical assault—the punch to the stomach—that sets off the legal case, which will in turn precipitate the national crisis, driving the country to the brink of civil war. To the extent that there is a resolution of the conflict at the core of the film, it only comes about when Yasser goads Tony into punching him in the stomach, which is the moment at which Yasser apologizes to Tony. Even though Tony loses his case, the film concludes on a note of begrudging acceptance between the two sides. Tony the mechanic has fixed Yasser’s car and Yasser has expressed some sympathy for the difficulty Tony and Shirine confront in their everyday life. No victor, no vanquished. Everyone saves face, but only by affirming their masculinity through throwing a punch. Is the viewer to understand that fistfighting is how real men apologize, working out their own need for violence as the means through which retribution or reparation or justice might be achieved? The fact that the legal case is thrown out—that justice cannot be achieved in the courts, whether national or international—might be read as indicative of the politics of the film.

The denouement is even more mystifying. Those who argue that the Lebanese civil war never actually ended do so in light of the problem that none of the political and sectarian leaders in the country were ever brought to justice. An amnesty law ratified in 1991 effectively codified the fuzzy principle of “no victor, no vanquished” (la ghalib wa-la maghlub), so the idea that the Samir Geagea-like character is the moral conscience of the film is an interesting counter-factual narrative, one in which Lebanese Christians get their recompense even after “losing” the war. Again, it is unclear what kind of emotional sense the final images are meant to evoke; shot from a helicopter as it draws away, up and out of the hurly-burly of Beirut, they elevate the viewer and the filmmaker alike above the petty squabbles of a tortured people who seem unable to avoid dramas they have created themselves that have their origins in wounded pride and machismo and unresolved vendettas. One wonders whether Doueiri is not simply throwing up his hands and choppering his way out of there himself. Or perhaps this is better understood as a moment of undecidability? As in other punctuated moments of collective violence in Lebanese history during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the message here would seem to be that restorative justice simply cannot be done because of the irreducible and irreconcilable claims of the warring parties.

The Insult is a skilled and accomplished film, to be sure, which is one reason why it earned a nod from the Academy Awards for 2018. The film raises difficult questions with universal significance about memory, justice and forgiveness. The very fact that Doueiri manages to take on these issues speaks both to his skills as a filmmaker and to the moment in Lebanese history when these questions could be screened and considered.

If there is a sense at times that the Lebanese civil war itself was a series of exercises in futility, though, then the film is itself particularly galling for the viewer given that there seems to be little reconciliation possible. For Doueiri, individuals would seem to bear responsibility for the making and unmaking of the country. But must the Lebanese people be represented in the international arena—at the Oscars—as being held hostage to primordial hatreds and personal vendettas that prevent them from reconciliation? Are those unquenchable thirsts for revenge what truly prevents Lebanon from moving forward? Are there not institutional or structural realities of Lebanese life that merit mention or critique? Has the Arab-Israeli conflict not played a major role in shoring up and perpetuating the destructive forces of sectarianism in the country? Who, in the final analysis, is fit to judge or be judged in Lebanon?

For showcasing the suffering of the Christian community in Lebanon, some critics claim that Doueiri is a partisan in the post-memory of the Lebanese civil war. And, indeed, in an interview, Doueiri said:

My background was with Yasser, and my present stance is with Toni. I grew up in Yasser’s world. With time continuing to pass, I now belong more in Toni’s world. This is how we evolve in life. I grew up always thinking that the Christian right wing had no narrative, that they were considered the enemy. Period. With time, you get to sit with them and negotiate with your neighbor and you start saying, “Wait a second.” We accuse those people of all sorts of things, but in reality, they aren’t this-and-this. They aren’t traitors. They are not collaborators. They are actually the opposite. They are the people who really fought, suffered, and sacrificed in defense of a certain ideal that I like. [2]

Setting aside the political ramifications of his statement, the more unsettling question at the heart of this film may be whether any of this actually matters at all. Doueiri seems willing to conclude there can be neither victor nor vanquished in law, in politics or in popular culture.

Endnotes

1. Ignatiy Vishnevetsky, “From Lebanon Comes The Insult, an Oscar Nominee that Pulls Its Punches,” AV Club, January 30, 2018.

2. Diana Drumm, “‘The Insult’: Ziad Doueiri on Humanizing a Story’s Politics,” No Film School, January 16, 2018.