Still from the 2021 film Farha, directed by Darin J. Sallam.

The film has kicked up questions of historical fact that professional historians of Palestine and Israel resolved long ago: Israel was a settler-colonial project, as Zionists before the state’s founding named it. The Nakba (meaning Catastrophe), which caused approximately 750,000 Palestinians to flee the fighting and become refugees, was the outcome of an explicit plan of ethnic cleansing. Palestinians were not instructed to run away by Arab leaders. During the Arab-Jewish fighting that lasted between 1947 and 1949, Zionist forces committed atrocities.

Alongside the countless academic books and articles are the novels, memoirs, archival projects and story-telling traditions that have preserved the chrysalis of evidence, recording, commemorating and analyzing the Nakba. They pin and fix the narratives of life in “al-bilad,” splaying the multi-colored joys of existence “back in the home country”—the taste of oranges and plenty—for the hungry consumption of those younger generations who did not get to experience it. The truths are there for anyone who wants them.

Yet, because Israel has so successfully propagated narratives contrary to evidence, the facts—and the lived experiences behind them—remain obscured, distorted and denied. In an attempt to generate international support for the Zionist project, the massacres (war crimes in today’s categories) that were committed against Palestinians during Israel’s war of independence were long hidden from view. Now and then, the realities of how Zionist forces conducted that war break into wider public view. And when they do, those who want to grasp onto fantasies of Israel’s army as a moral force scramble to tamp down the facts by any means necessary. It is a representational tug-of-war that may not be settled until one side falls all the way down. Farha gives another little tug. Conversation around the movie is showing again that historical proof takes a long time to convince.

More Than a Coming-of-Age Movie

Farha is not a documentary but an artistic production, one billed (inadequately) in the language of timeless human themes as a “coming of age story,” and “a powerful film of survival and lost innocence.”[1] It tells the story of a bookish 14-year-old village girl, eager to explore the world beyond her literary imagination. Farha’s father, a respected village leader, is eventually persuaded to let her go to school. But the disruptions of war halt the forward march of Farha and her society.

The action builds slowly. When Palestinian rebels first come through the village seeking support and arms to repel the Zionist forces, Farha’s father dismisses them. But when the war’s heat grows impossible to ignore, the villagers begin to flee. Farha’s father refuses to leave, and she, in an act of solidarity, stays with him. To protect her, he locks her in a pantry while he goes off, promising to return for her soon. Days pass. The viewer sits with Farha in her solitary confinement, and we wait. After witnessing a savage attack by Zionist forces against a Palestinian family that had returned seeking shelter for a pregnant woman to give birth, Farha eventually manages to bust out. Her hope, the creativity of her survival and the spark of potential in the mother’s delivery of an infant are all smothered by Israel’s violence. The film ends with Farha walking along a dusty road, the isolation of her confinement unrelieved by the world outside.

Farha reflects something of the multidimensional nature of Palestinian society and the conflict with Israel. A scene featuring a Palestinian collaborating with Zionist forces and another showing reticence toward armed resistance hint at nationalist taboos, showing that individual fears and self-regard were—and remain—in tension with what a nationalist struggle demands of personal sacrifice. In real life, most people are not pure heroes. More clumsily portrayed is one Zionist soldier’s difficulty in killing a baby. Watching from the bottom edge of an open window, Farha sees that, for some, evil acts require effort. But the excuse of “just following orders” does not erase responsibility.

The film has a contemplative pace. Shot from within a few meters of space, it demands viewers’ slow concentration, inviting us not only to look, but to witness. Through Farha’s big eyes the layers of existential disruption and dispossession that the Nakba has wrought on the lives of millions of people are not only seen but felt. The viewer experiences Farha’s joy at the prospect of going to school, the warmth of her father’s love for her. The relief when she drinks three cups of water after days of thirst is visceral. The film wants us to be made edgy by the claustrophobia of her dark confinement, horrified by what she witnesses.

And yet, public reaction among Israel’s defenders as well as supporters of the Palestinian cause has tended to focus on the film’s veracity. These reactions, like opposite poles of a magnet coming near, are particularly intense because of the film’s tempo and subject. Farha makes us feel, or feel again, or feel in a new way. Or it makes us want not to feel, but to look away, to deny, to escape. It has something to unsettle everyone.

Many Palestinians I have spoken to have not been able to bring themselves to watch the film, hesitant to sit amid the charnel house of emotion that it might produce. Some who watched it could not sleep afterwards. A Palestinian woman I know watched Farha at her family’s urging. Now in her eighties, she was 13 years old when the Nakba ended the Palestine she knew. When I asked her what she thought of the film, she grew silent and still for a long moment. Her typically friendly gaze dropped to her hands, thick with arthritis, telling me something of what she felt.

In an interview, the director and co-writer Darin J. Sallam, who describes herself as a Jordanian of Palestinian descent, observed, “it’s every Palestinian who sees themself in this story.”[2] She may be right on that score. But I think that Sallam is wrong in claiming that her film tells “a universal and timeless story that could happen anywhere, anytime.” Palestinians’ dispossession was enabled by a specific history of colonialism that nurtured the Zionists’ settler-colonial project, by the Nazis’ maniacal antisemitism that shook liberals’ faith in a universal humanism and by the antisemitism of the United States and Europe that denied Jewish Holocaust survivors a refuge. It may be unhelpful to view Israel’s settler-colonial project and Palestinians’ resistance to it as exceptional, as Brenna Bhandar and Rafeef Ziadah have explained. But it was these particular conditions that excused and justified the establishment of a new ethno-nationally exclusive state for the Jewish people.

In the same interview Sallam said, “I’m not a politician, but I decided to stay loyal to this story.” I think that it is this loyalty to the broad and the specific meanings of the Nakba, a representation of one character’s life that suggests a bigger but distinct phenomenon, that has stirred so much in viewers. To see that conveyed in the mainstream media is especially significant because the reality of Palestinians’ history and ongoing dispossession has been so regularly ignored and denied. Watching Farha is a political act, whether a viewer intends it as such or not.

Exodus and Myth as Fact

The narrative work that has gone into justifying Israel’s settler-colonial overtake of Palestine as the moral recovery of an ancient people’s land is as specific as it is vast.

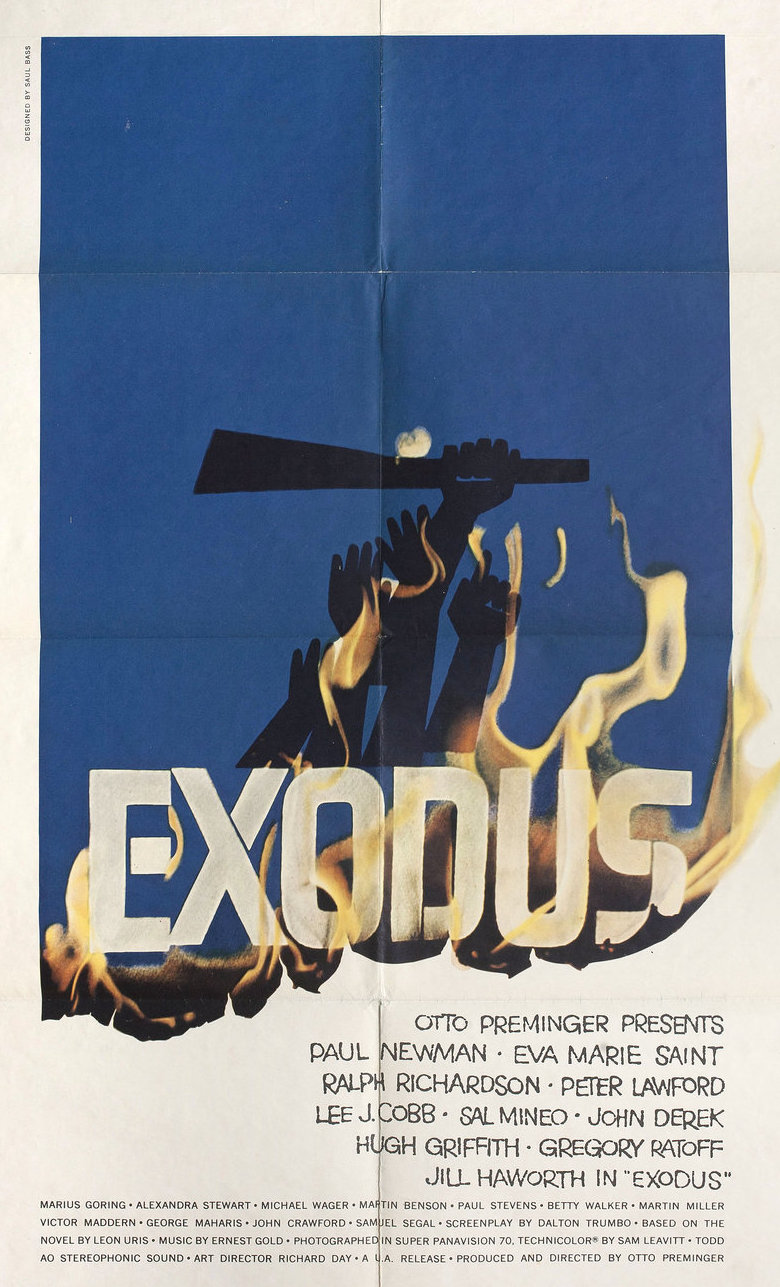

Original movie poster by Saul Bass for Exodus, 1960.

One prominent example is the 1960 film Exodus, based on Leon Uris’s novel of the same name. Starring Paul Newman, Exodus popularized and lionized Israel’s founding through a revised retelling of the story of 4,500 Jewish displaced persons on the SS Exodus, who were trying to breach the British blockade of Palestine. The journey of the real ship ended with three dead crew members and its Jewish passengers deported back to Europe. In contrast, Uris’s best-selling “nationalist saga” and the popular movie it inspired landed the Jewish refugees (portrayed as child orphans, not as the mostly adult passengers on the historical ship) safely on the shores of the Promised Land.[3] The unjust mass suffering of Jewish children is resolved in collective national triumph. The movie overwrote historical failure with fictional success.

Instead of offering victory, Farha—a word which means joy in Arabic—is lachrymose. The stellar cinematic qualities and remarkable acting of Farha’s lead, Karam Al-Taher who plays Farha, have not been mobilized to produce a happy false ending. Where Farha and Exodus do converge is on the field of historical debate, though they’re playing with different referees. Despite its clear operation in the realm of the mythical, audiences spoke of Exodus, the film and the novel, as “living, documented history,” writes English professor Amy Kaplan in her book, Our American Israel—a study of Americans’ dedication to the Jewish state.[4] Hailed by reviewers as a “powerful instrument of contemporary truth,” Exodus portrayed Israel’s founding as justice rising up.[5]

Whereas Exodus instantiated myth as fact, the truths in Farha are bone on bone reality. Like early audiences of Exodus, Palestinian supporters of Farha see in it a document of atrocities committed by Zionist militaries against Palestinian civilians. Randa Abdel-Fattah’s review in The New Arab begins with five paragraphs listing the facts of Palestinian history and ends by insisting: “The Nakba is fact, always fact, forever fact, unfolding fact, no matter Zionists’ denials, obfuscations, smears, intimidation or fantasies. The Farhas of the past and the present will not be silenced.”[6] Another viewer tweeted: “the film is so important in portraying the lived truth of those persecuted in the 1948 catastrophe.”

Unsurprisingly, rebukes of the movie’s truth-value by Israeli politicians and others were quick to follow the film’s release on the major streaming platform. In social media campaigns some Israelis called on their followers to end their Netflix subscriptions because it was airing this “false and anti-Israel film.” The “Iron Lion Zion” team—a group claiming to combat BDS and antisemitism—circulated a petition to Netflix to drop the film, accusing the filmmakers of “Blood Libel” and calling it a “total lie.” Hundreds of thousands signed on. In an apparently coordinated smear campaign, others were called on to give the movie a low rating on IMDB. Sallam received violent and hateful messages from strangers. In response to an interview with the director on the closing night of the Toronto Palestinian Film Festival shared online, one poster wrote: “the only truth is that this whole film is a LIE. If your history is true then you’d be able to make a film based on facts.”

Narratives Are Imposed, Not Permitted

Anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s work has become a popular reference for the idea that much of the past, even documented historical truth preserved in records, gets “silenced” by politics. In his book, Silencing the Past, Trouillot explained how the uneven power of facts enabled western ignorance of the most successful slave revolt in history, the Haitian Revolution. Both history as material process and history’s narration are at every stage marked by power. In blunter words, history is written by the victors.

Edward Said captured the quandary of history-writing for the non-victors as it relates to Palestine in his 1984 essay on the “permission to narrate,” published in the London Review of Books. He begins with a discussion of the commission headed by Sean MacBride—an international commission of six jurists, tasked with investigating Israeli violations of international law during the 1982 invasion of Lebanon. In his calm and courtly style, Said observed:

The political question of moment is why, rather than fundamentally altering the Western view of Israel, the events of the summer of 1982 have been accommodated in all but a few places in the public realm to the view that prevailed before those events: that since Israel is in effect a civilised, democratic country constitutively incapable of barbaric practices against Palestinians and other non-Jews, its invasion of Lebanon was ipso facto justified. Naturally, I refer here to official or policy-effective views and not the inchoate, unfocused feelings of the citizenry.[7]

The MacBride report stood in a long row of such reports—the result of tens of commissions of inquiry that have investigated the Palestinian issue. Beginning with the King-Crane Commission of 1919, jurists and other experts have been recording Israel’s mistreatment of Palestinians and listing the panoply of international legal agreements that they have broken in the process. The most recent such commission, “The United Nations Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and in Israel,” was established in 2021 and is significant for including the conditions of Palestinian citizens of Israel within its remit and for its designation as “ongoing.” A history of these commissions points to the weird and relentless expectations so many have that the facts can change things. But the facts alone cannot. The facts of Israel’s torture, murder, demolition, incarceration without trial, repression, censorship, dispossession have not moved those who could end the conditions producing these facts. It is, as Said says, the “unfocused feelings of the citizenry” that provide the fertilized soil in which political dynamics take root and strangle others.

Farha comes to a major streaming platform forty years after Said’s essay. The shape of power’s echo chambers has changed somewhat. Many of the gatekeepers manning the information barricades are different—as is the speed and means by which information moves—but influential outlets and western politicians still mostly refuse to name Israel as the perpetrator of its crimes. The UN has generated more investigative commission reports to establish, again, the facts of international law’s obliteration by Israel. But these reports continue to provide little grip against those tugging the rope toward the fantasy of Israel’s unique morality as a state. While supporters of Palestinian liberation multiply in solidarity with allied anti-racist struggles, so to do efforts to silence Israel’s critics. They now involve not only claims of antisemitism but also “the new antisemitism,” wherein certain criticisms of Israel (for example those that draw parallels between Zionism and racism) are defined as antisemitic.

What stands out as distinct from the context in which Edward Said penned his essay is the rapidly growing power of governments to silence research and dissent across liberal North America and Europe, including in Germany, France, Canada, the United States and Britain. The Palestine exception to freedom of speech is the thin edge of a wedge allowing fascist tendencies to control the political arena. In the United States, what began as laws preventing boycotts of Israel among public sector employees in several states, has rapidly morphed into laws targeting political action in the public sector against fossil fuels, guns and denying reproductive care. In Britain, the “Prevent duty” that requires surveillance and reporting of possible vulnerability “to being drawn into terrorism” by public bodies such as universities and schools has targeted Muslims and pro-Palestine activists. In this context of government-sanctioned Islamophobia, the Tory government continues its assaults against the basic freedom of expression, the right to strike and the right to boycott.

Meanwhile, amid an Israel that is lurching ever further rightwards, western politicians are criticized and disciplined for naming its fascism and apartheid. While the serial killing of Palestinians is mostly ignored or excused, Palestinian reprisals are immediately condemned. This relentless imbalance of care and recognition among western politicians seems to demand the repetition of the facts, as if the pile of proof can balance the scales. Yet as the scholar of fascism Robert Paxton identified, authoritarianisms do not depend on the truth but on “mobilizing passions.” In other words, the facts of the matters might be crucial, but they are not enough in the face of these many writhing tentacles of repression.

[Lori Allen is a Reader in Anthropology at SOAS University of London]

Endnotes

[1] Beatrice Loayza “‘Farha’ Review: A Most Brutal Coming-of-Age Story,” New York Times (December 1, 2022); “Closing Night: Farha,” Toronto Palestine Film Festival website.

[2] Armani Syed, “Why the Director of Netflix’s Farha Depicted the Murder of a Palestinian Family,” TIME (December 7, 2022).

[3] Amy Kaplan, Our American Israel: The Story of An Entangled Alliance (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018), p. 59.

[4] Ibid., p. 60.

[5] Ibid., p. 60.

[6] Randa Abdel-Fattah, “Netflix’ Farha challenges Israel’s cultural propaganda,” The New Arab (December 7, 2022).

[7] Edward Said, “Permission to Narrate,” London Review of Books 6/3 (February 16, 1984).