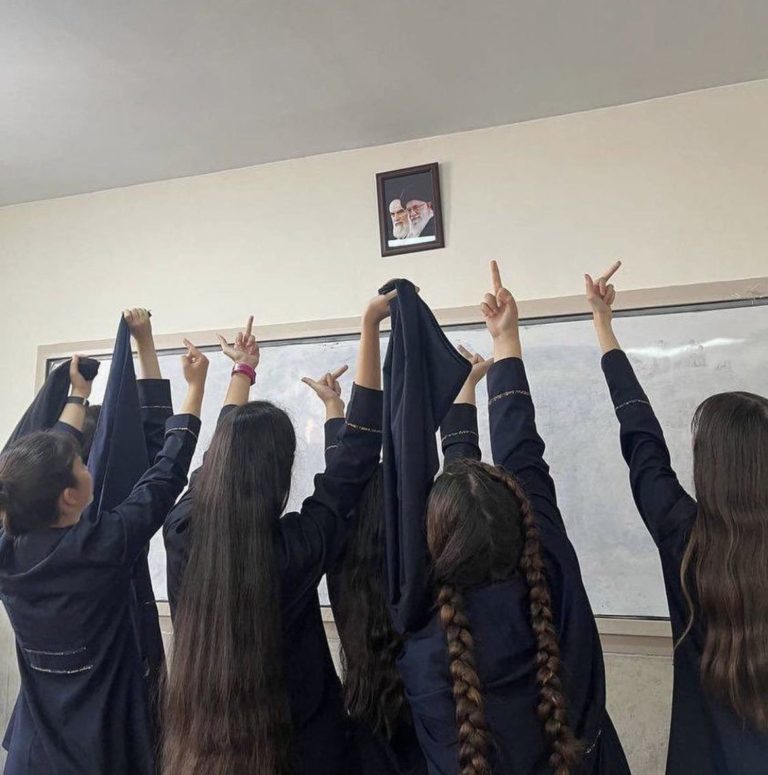

An image circulating on social media claiming to show Iranian schoolgirls protesting a picture of the supreme leader. Photograph: Twitter.

In them, men—yes! dozens of men—were featured discussing women’s bodies and grievances. Meanwhile, on the street, according to leaked documents published by Amnesty International, state forces were being instructed to “mercilessly confront” demonstrators, even to the point of death.

Two days later, when more than 80 cities held simultaneous demonstrations across Iran, Fars, the news agency managed by the Iranian Revolutionary Guards’ security apparatus, equated the unrest to a normal “couple’s dispute.” The main headline on their landing page read, “Compatriot! Let’s Talk to Each Other!” (“Hamvatan! Bia ba ham harf bezanim!”). This invitation to national dialogue came across as farcical in the context of women being shot at or beaten for removing or burning veils on the streets. Thousands of interlocutors in the supposed “national dialogue,” including activists, artists and at least 40 journalists from across the country, are currently being interrogated in jail.

For over four decades, secular and Islamic feminists have argued against the mandatory hijab, often by appealing to the Islamic government’s permitted means of persuasion. Even those who were not believers largely abided by the codes of conduct when talking to the nezam (the Persian word for the “regime” used by the Islamic Government). There were, of course, exceptions like Homa Darabi, who in 1994 immolated herself in protest against coerced hijab. Today, women and young schoolgirls en masse are done debating with the regime over whether they can exert their bodily autonomy. They are doing it.

Recent protests mark a tectonic shift in the method and rhetoric of expressing dissent in the Islamic Republic of Iran. The Green Movement in 2009 argued with the nezam, largely on its terms and using its terminologies. Demonstrators appealed explicitly to Islamic signs and messages, invoked and appropriated the memory of Ruhollah Khomeini, cited the legal texts ratified by the regime’s institutions and begged for the support of the Shia marja’s to no avail. The 2022 protestor has not bothered herself with any of these. She doesn’t care anymore about persuading the nezam. In 2009, wearing the green scarf was a symbol of dissent, as demonstrators resisted within the regime’s codes of hijab. In 2022, removing and burning scarves has become the ultimate act of rebellion. If the Green Movement played jiu-jitsu by converting the regime’s own sources of power in discourse, the #Mahsa_Amini movement is playing Karate: overwhelming the opponent by breaking his sacred discourse.[1]

The old guard Reformists are cautioning protestors to avoid such “disruptive” acts. Hassan Khomeini, the grandson of Ruhollah Khomeini who imposed Hijab with knives and clubs, has stated that “dialogue is the only way forward.”[2] It is, however, the failure of the conciliatory rhetoric staunchly employed by Reformists for the past three decades that has led to the confrontational rhetoric of protestors in the streets today.

Deliberation without Delivery

The Islamic Republic elite, whether Reformist or Principlist, moderate or hardliner, has a long history of invoking dialogue and debate during periods of contentious collective action as well as during the repression that follows. A series of TV debates between the regime’s ideologues and opposition in the spring of 1981 was followed by a bloody purge and widespread crackdown on any dissenting speech the same summer. Throughout the 1980s, the nezam employed terms like “debate” (munazereh) and “free discussion” (bahs-e azad) to describe the interrogation sessions of political prisoners.

Some of these so-called “debates” between prisoners and their interrogators were broadcast on radio and television. One program, which was made in the spring of 1984 upon the request of the Mashhad prosecutor general, featured five Marxist prisoners sitting next to and debating the then-Minister of Heavy Industries, Behzad Nabavi. Nabavi went on to become a prominent Reformist figure and was sentenced to six years in prison after the 2009 Green Movement protests.

The 1999 Student Protest was followed by a series of campus events. The Reformists introduced “Free Tribune” forums for disenchanted students to mildly express their criticism. Later, the Principlists (Iran’s conservative political faction) followed with the formation of the “Free-Thinking Platforms,” to clarify the nezam’s positions in a dialogical manner. In 2010, amid the Green Movement protests, the state TV booked benign opposition figures—those who had not been imprisoned—to participate in a series of live debates.

In November 2019, only a few days after a brutal crackdown of mass protests and a nationwide internet shutdown, Iran’s then-President Hassan Rouhani delivered a message at the closing ceremony of the annual Student Debate Tournaments stressing “the importance of public debate” and complaining about “the lack of constructive dialogue” in Iranian society.[3] Rouhani’s successor, the hardline President Ebrahim Raisi, made similar remarks on the twelfth day of the recent protests, inviting people who chant “Woman, Life, Liberty” to express their criticism in designated venues for dialogue and deliberation.

The Student Debate Tournaments were first conceived under the administration of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad as a means to release some of the pent-up frustration in universities after the Green Movement. They are managed by an organization dubbed “Academic Jihad,” which was initially established in order to curb public debate on university campuses as part of the regime’s Cultural Revolution of 1980. The landing page of the tournament website displays a quote by the Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, in praise of freethinking. The website proclaims debate to be an Ancient Iranian tradition, not a western import, citing a 2,500-year-old tale from the Achaemenid era which features seven Persian nobles debating the future form of their government. One makes a strong case for the benefits of democracy and the disadvantages of individual rule, another defends oligarchy. The debate ends when Darius, the soon-to-be supreme king of Persia, challenges all arguments and concludes that autocracy is the best form of government. The positive reference to this pre-Islamic tale was perhaps a Freudian slip for a regime that claims to embody Islamic values and boasts about abolishing the monarchy: neither authoritarians nor fundamentalists mind staging a dialogical exchange as long as, like for King Darius, they do not have to change their positions.

Since the start of Iran’s Student Debate Tournaments in 2012, time and again, variations of the resolution, “it is government duty to enforce hijab,” have been debated. Almost always, the team taking the negative side, that is, arguing against the government mandate to enforce hijab, has won—even when the players assigned to the role are pro-regime basiji students. Refuting the nezam’s positions in these debate tournaments, where the space for speech is neither free nor inclusive, requires care and finesse. Before participating, students have to sign a commitment letter agreeing not to offend “Islam, the sacred nezam of the Islamic Republic and its authorities.” Yet, even in the face of ample argumentation against mandatory hijab articulated within its boundaries, the nezam has only doubled down on its position.

In 2019, Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei met with a number of hardline supporters of compulsory hijab, including Mohammad Reza Zibainejad. Zibainejad—who once infamously commented that domestic violence, a pressing crisis in Iran, would be resolved if women submit to men’s authority at home—raised concerns that the current policing of the hijab was hurting the nezam’s popular legitimacy. The Supreme Leader disagreed vehemently, “Do not back off,” he is reported to have said four times, adding that otherwise, “God’s command will be violated.”[4]

Is Persuasion Possible?

Iranian dissidents have long grappled with a tactical, strategic and existential question. Can a dogmatist repressive regime be persuaded? If so, how? What kind of rhetoric makes for persuasion without prosecution? One recourse classically offered by rhetoricians is speaking with the same vocabularies of motive. As literary theorist, Kenneth Burke, describes it, “You persuade a man only insofar as you can talk his language by speech, gesture, tonality, order, image, attitude, idea, identifying your ways with his.”[5]

To observe how figures in the establishment rhetorically perform khodi-ness, you can tune into any one of the recent radio or television debates between Iranian Reformists and Principlists. These debates—which appear with increased frequency at times of popular unrest—tend to be aired on the less popular channels, like Shabakeh 4. In them, you will notice several rhetorical devices. Here is a cheat sheet should you ever get invited: Be implicit in the way you express criticism; cherry-pick and quote from Islamic texts and traditions (it helps to drop some phrases in classical Arabic); refer to the words and deeds of Ruhollah Khomeini; draw on the premises and promises of the 1979 Revolution; play the Othering game to prove where your ultimate loyalties lie (you can even throw random punches at the nezam’s excluded voices); insist that you only suggest reforming policies and not revising principles and that you do so because you deeply care for the wellbeing and sustainability of the “sacred nezam.”

The question of how to debate formidable dogmatists is not peculiar to Iran. In his book, How to Argue with Fundamentalists without Losing Your Mind (1997), Austrian philosopher Hubert Schleichert suggested a strategy he dubs “internal discussion.” It pretends to accept the assumptions, the basic convictions, of defenders of the faith and partakes in the reinterpretation and re-imagination of those convictions. In 2001, Schleichert’s book, already a bestseller in Germany, was translated to Farsi, during the height of Iran’s Reform Era.

On many occasions, even the nezam’s secular opposition and non-believers have resorted to the available repertoire of persuasion, engaging in “internal discussion,” in the hopes of reducing the hazardous costs of their speech. In 1995, Abbas Maroufi, the prominent Iranian novelist, who died in exile in September of this year, was summoned to court for publishing a poem, “the Republic of Winter,” in his literary magazine. Though the poem dealt in imagery of nature, the prosecutor claimed Maroufi’s intentions were to “disseminate lies against the nezam.” In his defense, Maroufi explained to the judge that he was an ardent “defender of the Islamic Revolution’s values” and that he considered it a religious duty, a “wājib,” to respect the Supreme Leader.[6]

Since its inception, the Islamic Republic has secured a form of obedience by compelling citizens to acquiesce to—if not believe in—the means of persuasion and modes of argumentation allowable by the regime. But paradoxically, it inserts a catch-22 condition. It does not allow defeat by its own tools and in its own game. Reformists positioned more closely to the regime have, for decades now, exchanged countless words debating fundamental issues, such as gender equality, popular sovereignty, secularism, human rights, freedom of thought and expression and normalizing Iran’s foreign policy. Monitoring these debates forms a major trend in Iranian Studies in the US and Europe. The debates have led to occasional intellectual metamorphosis, but institutional politics have largely remained intact. For those who push too hard, being on the inside, khodi, has not prevented repercussions.

Abdolkarim Soroush, a key member of the Cultural Revolution Council for the purge and Islamization of universities, who later transformed into a “Martin Luther” of Reformists, is now in exile. Hussein-Ali Montazeri—whose aides conducted summary executions in Isfahan during the 1979 revolution and who later became known as the “Human Rights Ayatollah” for defending the lives of political prisoners—died under informal house arrest. Mehdi Nasiri, the hardline editor-in-chief of Kayhan newspaper, who caused harm to many dissident intellectuals during the 1990s but who recently publicly repented from his former deeds, was denied a government license to publish his book in 2020.

The fate of such reformers inside the regime demonstrates that resorting to admissible means of appeal remains largely futile in persuading the nezam to change position. Although they tried to tread carefully—to not appear as a threat to the established order—they were still cast out of the circle of insiders immune from retaliation. Despite applying a timid tone, implicit language and identifiable rhetoric, their conversations with the nezam were perceived as subversive.

Talking Is Not Always Therapeutic

Perhaps it is a sign of occupational psychosis that the nezam’s Reformists still think they can urge the protestors to return home and give dialogue another chance. Their political imagination is trapped in the black hole of “internal discussions” from which no flicker can escape.

Schleichert warned about this very limitation of “internal discussion.” It may ceaselessly continue without any resolution while its ever-increasing subtleties drive the wider public to abandon it altogether. He proposed that sometimes the best one can do is to ridicule dogmatic principles and people—a method he calls “subversive laugh.”[7]

Since 2010, everyone from high-ranking politicians to prominent public intellectuals has commented about the necessity of initiating a national dialogue to resolve conflicts and bring health and harmony back to society. But they are flogging a dead horse, and no one has understood this better than the thousands of teenage school girls who have been literally giving the finger to the nezam while chanting “get lost.” If there is one civil and honorable form of censorship, it is theirs, for they are putting a stop to the feeble conversation of timid men with stubborn men. For them, the failure to persuade the regime has brought the possibility of catharsis, not through discussion but through determination.

[Ali Reza Eshraghi is Director of Programs at the Institute for War and Peace Reporting and a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Middle East and Islamic Studies at UNC-Chapel Hill.]

Endnotes

[1] Charles Kurzman, “Cultural Jiu-Jitsu and the Iranian Greens,” in eds. Nader Hashemi and Danny Postel, The People Reloaded: The Green Movement and the Struggle for Iran’s Future (New York: Melville House, 2011), pp. 7-17.

[2] “Sayyid Hassan Khomeini: Guftgū tanhā rāh birūn raft az buḥrān-hā-yi ijtima’i ast,” IUSNEWS (October 3, 2022).

[3] “Payyām ra’īs-i jumhur bi musābiqāt millī munāẓara dānishjūyān,” SSCR.IR News (December 23, 2019).

[4] “Nagūfte-hā-yī az bayānāt rahbar mu’ẓam inqilāb darbāra ḥijāb wa ‘afāf,” aatinews.ir (June 24, 2019).

[5] Kenneth Burke, A Rhetoric of Motives (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969), p. 55.

[6] Asnād va Parvānde-hā-yī Matbū’ātī Irān, Volumes 1-3, collected by Azra Farahani (Tehran: Ministry of Culture, 2005), pp. 180-188.

[7] Hubert Schleichertm, Baḥs bā Bunyādgariyān, trans. Mohammadreza Nikfar (Tehran: Ṭarḥ-i Nau, 2001), p. 184.