In the late 1920s, the Italian fascist regime implemented a campaign of ethnic cleansing in eastern Libya to create more land for Italian settlers and quell armed resistance to colonization. Ali Abdullatif Ahmida’s new book, Genocide in Libya: Shar, a Hidden Colonial History, examines this forgotten case of settler-colonial violence and the processes that led to the forced relocation of over 100,000 Libyans to special camps, resulting in the deaths of tens of thousands. Ali Abdullatif Ahmida is founding chair and professor of political science at the University of New England. Jacob Mundy, associate professor of Peace and Conflict Studies at Colgate University and a member of MERIP’s editorial committee, interviewed him in February 2022.

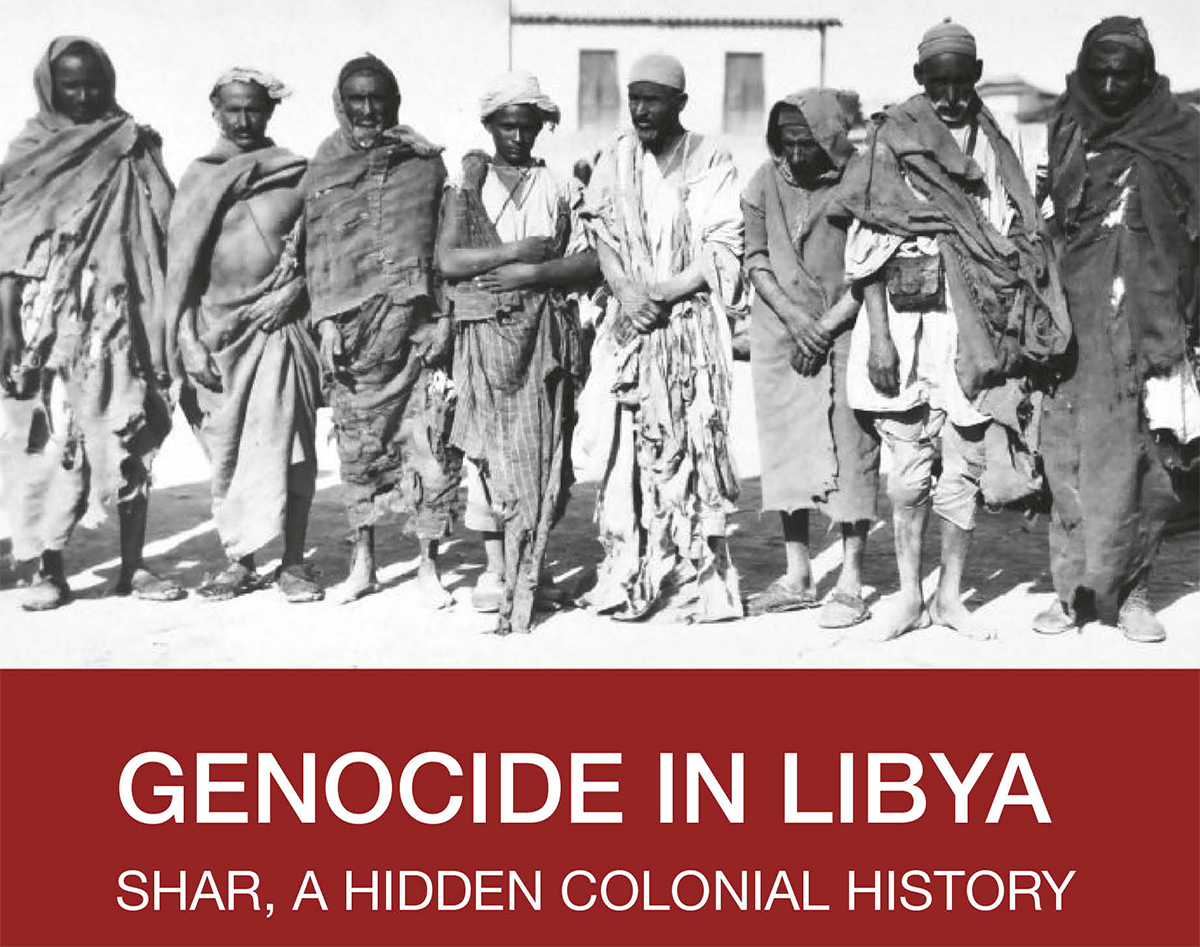

Part of the cover of Ali Abdullatif Ahmida’s new book, “Genocide in Libya: Shar, a Hidden Colonial History,” published by Routledge, 2021.

Jacob Mundy: The project of Italian settler colonialism in Libya is not well known, even among regional specialists. Can you provide a short sketch based on your work? You describe it as brief but intense.

Ali Abdullatif Ahmida: Italy looked at Libya as the “fourth shore,” an extension of Italy like the French treated Algeria—the same mentality. It was a shorter period of colonization (1911–1943) but very brutal. The dream was designed by the so-called liberal colonial state in 1911. The goal was to settle between 500,000 and 1 million Italians, especially the landless peasants from southern and central Italy. They were supposed to be settled mainly in eastern Libya, in the fertile Green Mountain area. The Italian settlers also thought that they would be welcomed by the local population, assuming the Libyans had resented Ottoman rule (1551–1911). That was a big miscalculation. The Libyan resistance to Italian occupation continued for a long time.

When the fascists under Benito Mussolini arrived in 1922, they came with an even more vicious, more brutal plan—they decided to clear the land of Indigenous people. The concentration camps are, as I argue in the book, linked to the clearing of the land for the settlers and especially to defeating the resistance in eastern Libya. The draconian Italian policy was to move the native civilian population that supported the anti-colonial resistance—between 100,000–110,000 people with their herds—to the deserts of Sirte. Two-thirds of them perished there. The first wave of settlers, a major wave of 20,000, arrived in 1938.

The other myth among the Italian elite was that Italian immigrants were mistreated in South America, North America and other places. The settlers believed that since Libya had been part of the Roman Empire they were simply reclaiming it so they could have a place of their own. The idea of reviving Roman Africa was a very integral part of the propaganda to justify colonization. And after that, more settlers came. Although the Italian fascist experiment in colonialism ended in 1943, when they were defeated by the Allies in World War II, many settlers stayed until 1970.

Jacob: Libya’s population was roughly 1.5 million at independence in 1951, so the ethnic cleansing campaign may have targeted upwards of 10 percent of the population. Why has settler colonialism in Libya, particularly the violence that made it possible, received so little scrutiny?

Ali: Libya is least known in Western scholarship—and even among scholars of North Africa—for historical reasons. Settler colonialism in French North Africa—Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco—is very well known because of its long domination and control. There is a whole body of literature, and we are still dealing with its legacies. Even the definition of the Maghrib often excludes Libya. And you know, after 1969, Libya was not open to Western scholars. Only a small number of scholars were let in—Lisa Anderson, Dirk Vanderwalle and a few others. This situation was very different from other countries. I spent 15 years investigating and researching the genocide because nobody knew about it. When I published Forgotten Voices, I was invited to Yale, UCLA, Columbia and other major institutions in North America and Europe, and the first thing I would ask is “Have you guys heard about the concentration camps in Libya?” No one knew about them, which confirmed for me that the Libyan case had dropped out of modern scholarship.

Jacob: In genocide studies, there are always references to the Namibian (Herero-Nama) and Armenian genocides as a precursor to the Holocaust. How did the case of the Italian genocide in Libya also become an important predecessor to the World War II genocides in Europe?

Ali: I was reading an Italian journal published in Libya, and I read about a visit by [the Nazi military leader Hermann] Goering that was reported as a glorious visit to the colony. When I pursued that lead I discovered, according to a German historian, that Nazi leaders—not just Goering but Heinrich Himmler and others—visited Libya because they thought that Italian Fascism was the most successful example of clearing the land and paving the way for settling, which went along with the Nazi dream of settling 15 million people in Eastern Europe. And that was an incredibly horrific discovery.

I hope my book will start a new debate, a new paradigm shift: that we begin to pay attention to the fact that the Libyan case, even more alongside the German colonial experience, is linked to European history and genocide studies. The Libyan case is the most glaring and the most powerful example of colonial genocide in North Africa, but, at the same time, it has been ignored for 70, 80 years. I hope that this book will be a real turning point—that we begin to dig more, ask new questions and see the linkages. And that we place more pressure on the Italian state to open currently closed archives.

Jacob: I was really struck by your discussion of the Italians’ use of Eritrean auxiliaries—askaris—as a security force. That fact exposes the weakness of analyses rooted in neatly enclosed nation states or regions like “Europe,” “the Maghrib” and “the Mediterranean.”

Ali: Mediterranean studies, to me, is a noble idea, but it’s also quaint and ahistorical and misses the real social history, the interconnections, the contradictions, the linkages and the ability to ask the hard questions. My book is asking hard questions. I try to confront two dominant paradigms—the old nationalist paradigm that I was brought into as a youngster coming from my family that was involved directly in Libyan anti-colonial resistance and by my whole education. And secondly, the area studies paradigm. I edited a book in 2000 called Beyond Colonialism and Nationalism in the Maghrib to question these things, and it was published in Arabic after a lot of reluctance because they didn’t like my critique of nationalism.

The askaris are very important because Eritrea became a source of poor peasant labor for Italy just like North Africa was a source of poor peasants who tried to make ends meet by becoming colonial soldiers in the World Wars. The askaris and Libyans who collaborated with the Italians open a whole can of worms because of that complexity. That history we’re talking about is in eastern Africa, in northern Africa and in Italy. The terrain is very, very complex. And it’s not just an area, this country or that country. We also have to deal with postcolonial conflicts over who became a Libyan citizen, who became an eminent personality, who was deported and the legacies of these institutions and boundaries that still echo around the region.

This book [Genocide in Libya] is not meant to be conclusive, but to bring out Libya and Libya’s brutal, genocidal colonial history. And to get rid of that common and really absurd way of thinking that goes “I don’t know anything about Libya, so I’m going to talk about tribalism, I’m going to talk about [Muammar] al-Qaddafi, about regionalism or religion.” Who doesn’t have regions? Who doesn’t have these social complexities?

Jacob: What was the process that led you, as a political scientist, to explore alternative archival sources, particularly given the Italian policy of colonial amnesia surrounding these atrocities? This genocide has been an open secret in Italian history. How did it become one of those things that is known but not talked about?

Ali: Yes, it’s almost like a secret unless you go through with the work. Otherwise, you don’t understand—you are not even aware of it.

I was guided by a group of terrific Jewish American professors [in political science] at the University of Washington. My late mentor was Daniel Lev, who was not interested in typical political science models and quantifying, so he pushed me and my classmates to understand the historical, the theoretical, the comparative and the critical. And then Daniel Chirot and our beloved Ellis Goldberg. They all pushed me to do the comparative work and go beyond area studies but also to take social history very seriously. Michel Foucault said that we need to investigate the history of the present. So, in that sense, I was really lured into doing historical sociology—not just historical sociology of the Middle East but also Africa and Europe—as well as anthropology. I took four courses in anthropology to prepare for archival and oral history. And so, for my dissertation, I did archival research and oral interviews because most of it was about the nineteenth century and early twentieth century.

So what happened? I learned Italian and I went to Italy to do archival research. And I went to Libya and Egypt to do archival research. The problem was that they kicked me out of the archives. It turned out that some officials at the Italian archives were ex-colonial officers and somewhat fascist. Later I realized that many fascist officials were rehabilitated by the Allies and Italy never confronted its fascist past, especially in the colonies. The second important thing is that Italian society, with a few exceptions, still refuses to confront the horrors of the colonial period, especially in Libya. Angelo del Boca, Giorgio Rochat and Eric Salerno have written on these issues, but the Libyan genocide was otherwise completely ignored. It was then I discovered that the secrecy in Italy is really an issue. If you don’t understand this as a researcher, your work is really doomed.

But then Angelo del Boca told me, “Ali, don’t even bother. I spent 40 years in the archives. There is nothing there. They manipulated the archives.” Del Boca—a fine historian, a giant standing against the silence and amnesia—advised me to go talk to Libyan survivors. And I went to Libya and asked Libyan scholars of Italy who told me the same thing. And that was the best thing I have done—to go to eastern Libya every summer for ten years to try to find the survivors. I interviewed some people three times to make sure that the stories were correct. And then, after that, I went with my camera to the location of the concentration camps, and I took photos and did fieldwork. What I discovered was more shocking than I had expected, especially when I came face to face with the cemeteries and the mass graves. That was the most painful experience in the whole decade and a half of doing research.

Why should we assume the archive has facts? It reflects certain secrets of a state, a certain narrative, a certain language. And unless we really contextualize it, we become part of the problem. We need to look very carefully at archives, and the archive is sometimes a part of the problem. And the fact that we can’t find something doesn’t mean that we cannot do history or analyze institutions or tragedies like genocide.

Jacob: What do you have to say to scholars who question the evidentiary status of oral testimony and poetry, which is so central to this book?

Ali: If you take seriously the humanity and the agency of ordinary people and the way they express themselves, they are very articulate. But to listen and comprehend what they are saying, and how they’re saying it, we need to be reflexive. Like the anthropologists for the last 40 years, when they began to say, “Gee, our discipline was invented by the colonial state as colonial knowledge, and we need to confront that.” I’m not saying that the postcolonial turn is the solution, but I was educated in independent Libya and also in Egypt, in college where modernization was the dominant paradigm. It dismissed ordinary peasants and ordinary folks; everything had to be a formal document.

What I did [in Genocide in Libya] was what the anthropologist did—to look, pay attention with respect and take the agency of the ordinary survivors very seriously. And then understand the language, their metaphor, their style and their mode of communication, and how they express themselves through a very incredible memory of what happened in the camps. They composed poetry to express the agony, the trauma, the grieving. So I had to, at the beginning, overcome my own modern education. And I began to understand a language within a language or culture within the culture; most of them were semi-nomads and I had to understand that to comprehend the ways they express themselves—they were articulate, they were brilliant. I think I find that my previous attitude, and forgive me, some of my colleagues who dismiss [oral testimony] as not evidence, it’s very arrogant and very patronizing.

Jacob: The final part of the book, where you link colonial violence to Libya’s troubled present, reminded me of debates about Algeria in the 1990s and the extent to which the violence of the civil war was (or was not) rooted in the colonial experience. You raised this question with respect to what has happened in Libya since 2011. How do you make those historical linkages?

Ali: Well, I’m glad you asked. That question is very significant. Algerian and Libyan history are probably the most brutal; they went through the most brutal settler-colonial experiences in North Africa. No wonder they are similar in many ways, and I think it’s something the postcolonial state and societies still grapple with.

What I tried to do after excavating and interrogating what happened in the camps and the genocide is to ask myself, how does it directly impact the postcolonial period? We had so much pain and so many wounds, so many people who collaborated, people who resisted, people who were murdered, people who were hanged, people who were pushed into exile. Under the monarchy and Qaddafi’s Jamahiriya State, in many ways, there were efforts to try to break the silence [on the genocide], but in a really top-down way. But then some of the violence used against opponents echoed some of the violence of the colonial state. I don’t say that so bluntly in the book, but I feel like this way of dismissing critics, opposition and rivals in society has really impacted Libya.

The Qaddafi regime and the monarchy made a choice as the leaders of Libyan independence to focus on moving forward. But I think it was wishful thinking. The state was built, and the modernization and education were spectacular. But the Qaddafi regime also built its legitimacy on populism. “Nobody cared about you!”—that’s what Qaddafi used to shout all the time to Libyans. He began to make that part of his legitimacy and that of the revolutionary government, a so-called populist government, that it was giving you justice and a voice after what had happened under the Italians. Then, the 2011 uprising came, which unfortunately turned into a civil war, taken over by militias and mercenaries and foreign groups and tremendous, unprecedented corruption. At the early stage [of the uprising], the young men and women who protested in eastern Libya took the anti-colonial resistance heroes, Omar Mukhtar and others, away from the regime.

The repression of memory and collective amnesia that exists until today is really the challenge of the future. This book is not just a scholarly book; I wanted to do a thorough investigation. I saw myself as investigating collective crime, and therefore I had to be thorough, I had to be really patient, and I had to follow the trails. But in Libya, people say, “Professor, this is good what you did, but tell us how to resolve our current problems.” They are referring to the civil war, fragmentation, infighting, the collapse of the police and the army and the blocking of rebuilding. I say, first of all, Libya is big, and regionalism is a fact. But it’s not unusual for large countries to have problems with regionalism. Secondly, what country that has 20 million pieces of arms and weaponry, and had its police, its army, security operatives and borders completely dismantled—wouldn’t be fragmented? They are looking for a simple recipe, a book to provide the solution, but history and postcolonial cultures are complex and contradictory.