An Iranian man takes a selfie with his vaccination card at a vaccination center in Tehran, Iran September 20, 2021. Majid Asgaripour/WANA/Reuters

During the early stages of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020, the ideological prescriptions of self-reliance and resistance were presented by the government within a discourse of responsibilization, which is the process where responsibility for certain tasks is shifted from the state to individuals. Although the state imposed restrictions on travel and gatherings and implemented closures like most governments, it framed efforts to defeat the virus primarily in terms of individual actions, behaviors and sacrifices to be carried out by members of society, not the state. In March 2020, for example, the government encouraged universities and private companies to combine forces to develop and produce health care products like masks and disinfectants.

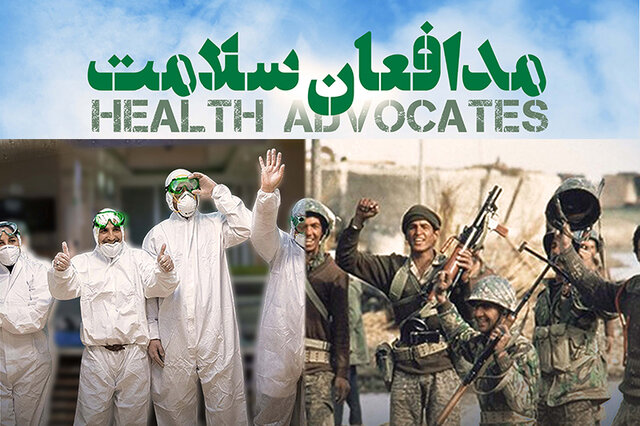

Fig. 1 Health advocates confronting COVID-19 juxtaposed with Iranian soldiers. ISNA

Referencing the history, memories and experiences of past moments of crisis when members of society demonstrated resistance and self-reliance–most notably during the Iran-Iraq War, government messaging focused on the agency and acts of individuals as the most important means for confronting the virus.

As the dynamics of the pandemic shifted, however, and the most widely recognized solution to the virus’s spread became the acquisition and disbursement of vaccines, the promotion of well-trodden state narratives of self-reliance and resistance couched in terms of individual agency was no longer sufficient. In a health crisis like COVID-19, the job of procuring, producing and distributing vaccines is one left mainly to governments. Notions of self-reliance and resistance continue to feature heavily in regime messaging around its coronavirus response, but now that the onus of responsibility has fallen squarely on the government to distribute a vaccine, the balancing act with political ideology has become more tense and confused.

Resistance, Solidarity and Society

When COVID-19 first appeared in Iran in February 2020, the government response was plagued by attempts to conform long-standing ideological positions with crisis mitigation policies to combat the spread of the virus. The championing of the country’s resistance to the West dictated important government actions, like declining medical equipment from foreign sources. This type of government response was further compounded by the circulation of misleading and false information about the origins and spread of the virus, while political in-fighting, factionalism and competition among centers of civilian, military and clerical power within the state led to contradictory statements by government officials. International sanctions on Iran hindered the acquisition of medical supplies and access to international financial instruments, which amplified the dire health impacts of the pandemic and hampered the government response.[1] Government corruption, an ongoing problem, has impacted decisions regarding vaccine production and reportedly led to regime insiders cashing in on the development of home-grown vaccines.

In the early months of 2020, the regime sought to promote its handling of the crisis by focusing on the competency and agency of its own citizens to adapt to new social and behavioral realities. As Maziyar Ghiabi describes, Iranians independently engaged in acts of solidarity and trust at the pandemic’s outset. State actors highlighted this societal competence and self-reliance as an already present characteristic of an idealized Islamic society and one in line with the teachings of the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. The government created narratives and visual iconography that strengthened these claims of individual sacrifice. These images—displayed in public and circulated through state entities and affiliated media—were used to mobilize citizens in the collective struggle with COVID-19 by suggesting that the experiences of life in Iran as a country under threat were no different now than during the war with Iraq, and by popularizing terms like “Health Defenders.”[2] Notions of solidarity and unity dominated the messaging campaigns. One of the most prevalent regime-sponsored slogans during the early days of the pandemic was “Jihadists of Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow,” a clear effort to connect the contributions of individuals during the present crisis to those of the past. The overall message was clear: As a society we have been here before and persevered through the sacrifice of individual citizens. By shifting responsibility to citizens, the government was able to deflect questions about its own handling of the crisis.

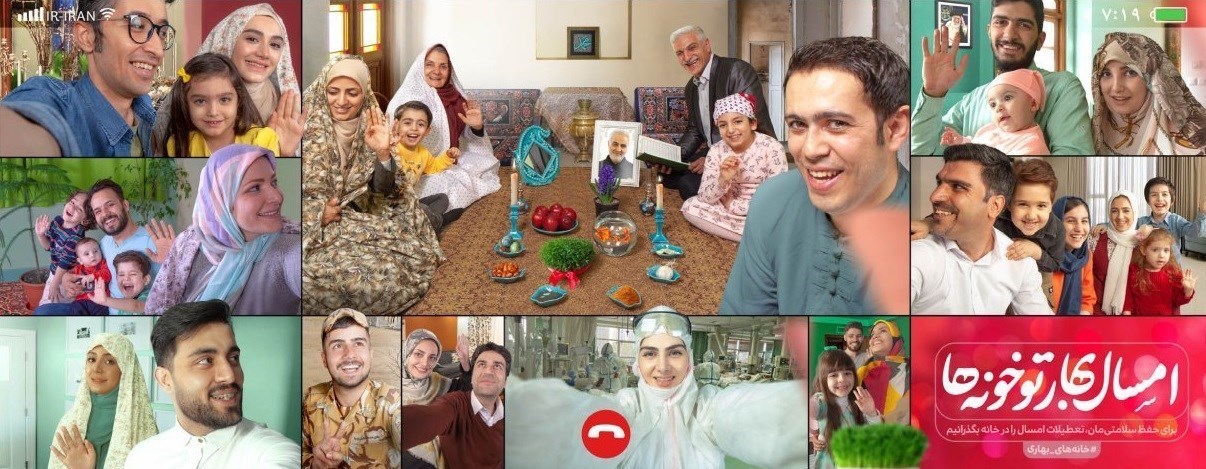

Fig. 2 “For protecting our health, spend this year’s holiday at home.” Tasnim News

Even when the government imposed rules such as home quarantine or partial lockdowns, thereby curtailing freedom of movement and restricting communal solidarity, the measures were not presented as a form of isolation but cast as the re-implementation of togetherness. For example, a billboard at the Vali Asr intersection in Tehran in March 2020 proclaimed that Iranian-Islamic society, and its individual members, were well-equipped for these measures that relied on family cohesion.[3] (Fig. 2)

Fig. 3 The difference between Islamic-Iranian culture and the materialism of the West. Office of the Supreme Leader

Reflecting in May 2020 on several months of lockdown, Khamenei was pleased with its positive impacts on family life, a central theme in his writings concerning the healthy functioning of society.[4] “During this time, the role and place of the family in Islamic-Iranian culture became more apparent,” he stated, “while in countries where the family doesn’t have the proper foundation and meaning, the period of home quarantine was not tolerated and comprehended in this way.” The latter was a clear reference to the societies of the West.

With the entire world facing the nearly identical and simultaneous need to enact social-distancing measures, quarantines and lockdowns, Khamenei argued that individuals in the West were ill-equipped to handle the crisis due to the social and behavioral norms endemic to their societies.

In a poster released by the Office of the Supreme Leader in the spring of 2020, the perceived differences between Iranian and Western responses to the pandemic were made abundantly clear. (Fig. 3) While stating that Iranian society responded with collective sacrifice and solidarity, it suggested that Western societies hoarded medical supplies and stockpiled toilet paper, groceries and guns. The individualism and materialism of the West, exemplified by a depiction of President Donald Trump as a stick ‘em up outlaw of the American West ready to take what he wanted by force, was contrasted with a generic frontline worker in Iran, at the ready to serve society by taking the temperature of another. The strength of Islamic-Iranian culture, according to Khamenei, lies in the capacity of its individual members to retreat to family unity and express societal solidarity, as opposed to Wild West capitalism. (Fig. 4)

The Travails of Self-Reliance

The Iranian government could not meet the unfolding challenges of the health crisis solely by calling upon ideological norms and ingrained state narratives. The government’s attempts to construct and promote a vaccination campaign—whose success largely depends on relying on other countries for vaccine acquisition—illustrates the state’s dilemma. Advocating self-sufficiency and self-reliance under these conditions directly challenges the relevance and credibility of regime ideology and exposes government incompetency.

Fig. 4 “Cowboy Trump” stealing masks. Office of the Supreme Leader

The exposed fault line between maintaining a hardened ideological stance and confronting the uncompromising reality of the coronavirus crisis has led to contradictory and mixed messages. In January 2021, in a televised speech, Khamenei declared that American and British vaccines were banned from entering Iran. In a tweet, subsequently hidden by Twitter for violating its rules on vaccine misinformation, the Supreme Leader claimed the United States and Britain may seek “to contaminate other nations” through the distribution of vaccines. Various Iranian government officials responded in support of Khamenei’s proclamation, including Ebrahim Raisi, then head of Iran’s judiciary and currently the country’s president, who emphasized the benefits of pursuing a domestic vaccine. Minister of Health Saeed Namaki framed the Supreme Leader’s decision as stemming from his responsibility to protect the population just like “the father of a family,” a role which the Supreme Leader is often considered to fulfill.[5] Grand Ayatollah Makarem-Shirazi, a frequent supporter of conservative policies, offered his opinion by noting that American and British vaccines should be avoided if fears exist over potential “damage and contamination.” Khamenei’s ban led many relatives of those who died from COVID-19 to blame him for the death of their loved ones, even causing some in the government to backpedal and claim the ban was misunderstood. Blocking the importation of Western vaccines was not, however, simply an ideological matter of self-reliance but was partially dictated by the political clout of regime insiders hoping to score a financial windfall from domestic vaccine development and distribution. Vaccine importation was also delayed so that domestic organizations could profit, with some receiving advanced payments from the government but failing to deliver a product.

Fig. 5 The winding road of technological achievements. Office of the Supreme Leader

The production of several homegrown vaccines provided the Iranian government with one possible route for bringing the ideology of self-sufficiency and self-reliance into closer alignment with the actual praxis of its vaccination program. In March 2021, the government claimed that at least three homegrown vaccines had reached the phase of clinical trials, including the Fakhra vaccine, named after the assassinated nuclear scientist Mohsen Fakhrizadeh. But despite attempts to drum up support for the vaccine by touting it as an example of national self-reliance and through the use of Fakhrizadeh’s name and status as a national martyr, the vaccine was discontinued in October 2021 due to a lack of volunteers for trials. Only one of the domestic vaccines—the CoVIran Barakat, developed by the parastatal organization Setad controlled by the Office of the Supreme Leader—has reached mass production. Nonetheless, close to ten vaccines are reported to be in development in Iran.

The regime has faced increasing opposition and unrest over its mismanagement and handling of the crisis, even resorting to jailing several Health Defenders in December 2021 who sought to sue the Supreme Leader and the government over its pandemic response. Insufficient vaccination rates, skepticism toward domestically-produced vaccines and the flocking of Iranians to neighboring Armenia or the black market to get vaccinated, led to an about-face concerning vaccine acquisition. Amidst a fifth wave of the pandemic in August 2021, President Ebrahim Raisi ordered the government to set aside resources to import vaccines, while Khamenei declared in a televised address that vaccines “whether through import or domestic production” must be supplied “in every way possible.” Several days earlier, while receiving his first dose of the CoVIran Barakat vaccine, Raisi had already recognized that the circumstances of the pandemic trumped political ideology: Domestic vaccines would be relied upon as much as possible, but to the extent they proved insufficient, other vaccines would be imported.

Khamenei too admitted much the same by stating that vaccines “must be accessible for all people from any possible way, be it domestic production or through importing.” During this time, Khamenei offered a legal opinion in response to a question about the necessity of the vaccine, by noting that, “If the Islamic government announces regulations in the public interests of the country, then everyone must act.” The vaccination issue was no longer framed as one that must cohere with the ideology of self-reliance and self-sufficiency, but one of government authority. The epidemiological crisis of COVID-19 had forced the authorities to concede. The struggle over formulating a successful vaccine campaign reveals the tension of attempting to safeguard society while still articulating a national narrative of self-reliance.

The Pursuit of a Healthy Regime

As early as March 2021, just before the Iranian New Year, a group of parliamentarians put forth a plan to establish the “Organization of Islamic-Iranian Medicine.” Among the aims of the organization would be to “use Islamic teachings and instruction in Iranian (traditional) medicine in the fields of prevention, treatment and health” and “to promote a healthy lifestyle in accordance with Islamic teachings.” In recognizing Iran as “one of the [historical] centers in Islamic and traditional medicine and medical knowledge,” the proposal sought to incorporate Iranian-traditional and Islamic knowledge in the health and medical infrastructure of present-day Iran alongside modern medicine. The proposed plan, as well as a subsequent version made public in the fall of 2021, garnered opposition from medical professionals and academics in Iran for being “unethical” and “not only wrong, but dangerous.” As of early 2022, at least one parliamentarian serving on the Majlis’ Health Commission opposed the plan for the danger it posed in upstaging and possibly superseding the role already played by the Ministry of Health.

Fig. 6 “Heroic Nation.” Khattmedia Telegram channel

The fate of the organization is uncertain, and along with it the extent to which the government will strive to favor notions of self-reliance and resistance during the pandemic, in this instance the promotion of an indigenous form of “Islamic-Iranian” medical knowledge. It is another example of the tension created by government attempts to forge solutions to an unfolding health crisis in a way that adheres to the regime’s longstanding political ideology. The story of COVID-19 in Iran, like elsewhere, continues to be written. But what is emerging with greater clarity is how the regime will include the memory and experience of the pandemic era in the official narration of life in the Islamic Republic. This period seems likely to be memorialized as another critical juncture on the path of crisis and survival winding its way into the future—charted by domestic successes achieved through self-reliance and resistance and defined by the actions and sacrifices of a heroic nation. (Fig. 5 and 6)

[Kevin L. Schwartz is a research fellow and Deputy Director at the Oriental Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences in Prague, Czech Republic. Olmo Gölz is a lecturer in Islamic and Iranian Studies at the department for Oriental Studies, University of Freiburg, Germany.]

Endnotes

[1] Zohreh Bayatrizi, Hajar Ghorbani, and Reza Taslimi Tehrani, “Risk, Mourning, Politics: Toward a Transnational Critical Conception of Grief for COVID-19 Deaths in Iran,” Current Sociology 69/4 (2021). Sima Shakhsari, “Voices from the Middle East: Doctors, COVID-19 Patients and Dilemmas of Treatment under Sanctions in Iran,” Middle East Report Online, April 17, 2020.

[2] Kevin L. Schwartz and Olmo Gölz, “Going to War with the Coronavirus and Maintaining the State of Resistance in Iran,” Middle East Report Online, September 1, 2020.

[3] Kevin L. Schwartz and Olmo Gölz, “Visual Propaganda at a Crossroads: New Techniques at Iran’s Vali Asr Billboard,” Visual Studies 36/4-5 (2021).

[4] Ayatollah Sayyid Ali Khamenei, The Compassionate Family (AIM Foundation, 2017), pp. 29-33.

[5] Shahram Khosravi, Precarious Lives: Waiting and Hope in Iran (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017), p. 30.