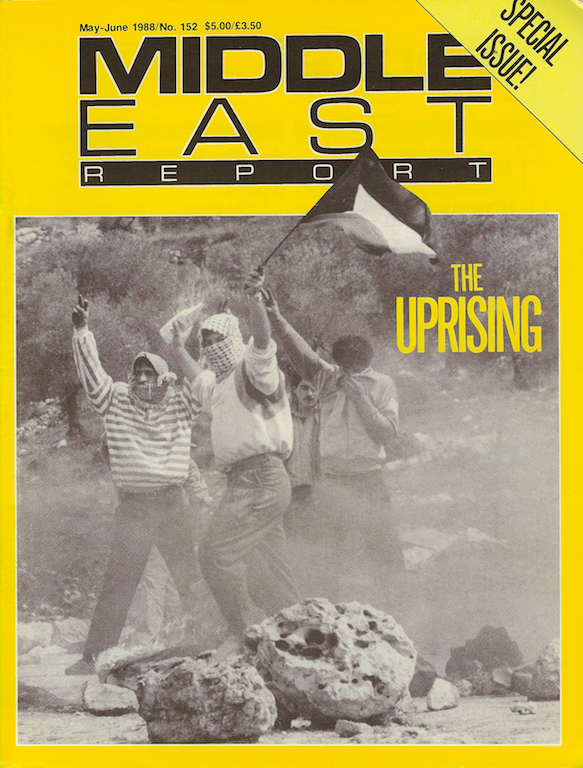

Cover photograph of Beita village, West Bank, early March 1988, by George Azar.

Across several issues, informational articles by Lisa Hajjar, Mouin Rabbani, Martha Wenger and Joel Beinin on “Israel and the Palestinians, 1948–1988,” “Israel’s Military Regime,” “Jerusalem: A Primer” and “Palestine for Beginners,” helped further MERIP’s effort to educate generations of young people in the United States and around the world about a new era of Palestinian struggle. There were also on-the-ground close reads of the machinations of the Israeli state, its extractive and expansionist policies and its eliminationist violence as well as critical perspectives on Israeli society and its ideological, social and political fault lines, or as MERIP termed them, “points of stress.” Benjamin Beit-Hallahmi wrote, for example, about the arrival of the Black Hebrews and their reception by white Zionists. Correspondents, sometimes anonymous for fear of reprisals, sent in dispatches on the Intifada’s regional repercussions.

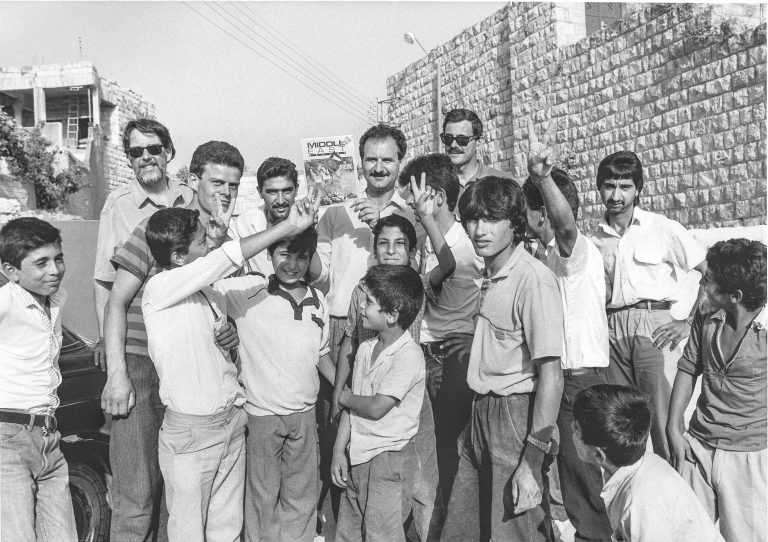

In June 1988, Joe Stork and Jim Paul, MERIP’s editor and publisher, were reporting from the West Bank. The Intifada was already into its second phase, advancing in both organization and tactics, but the media had mostly moved on. Palestine was no longer on the front pages, and the week of television reporting from Jerusalem by Nightline’s host Ted Koppel had ended. But MERIP remained. It covered the Israeli and US responses to the first Intifada; transformations in the PLO’s relationships to Palestinians in the Occupied Territories and in Israel and the changing strategic decision-making among the Intifada’s underground leadership. Articles also assessed the economic and political strategies mobilized by multiple Palestinian sectors and their effects. Authors investigated how economic boycotts and tax strikes were taking shape, and questioned if they could work in eroding the profitability of the occupation. MERIP followed Arafat’s trip to Europe in the lead up to the historic 1988 meeting of the Palestine National Council in Algeria as the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) sought to shore up support from European socialist parties and international solidarity networks against the occupation. Micah Sifry reflected on the limitations of electoral politics in the United States from the standpoint of Jesse Jackson’s then singular call for solidarity with Palestinians during his 1988 presidential run.

MERIP interviewed organizers, scholars and workers. It wove together textured and often moving vignettes and reflections on everyday life under brutal subjugation and resistances to it without flattening the class, gender, regional and other differentials of that experience. Rania Atalla, for example, wrote on Ahlam’s struggle against the debilitating effects of tear gas inhalation and the politics of disability during revolt.

Joe Stork, Beshara Doumani and Jim Paul visiting Beita village in June 1988. The cover image of issue number 152, held up by Doumani, was taken by George Azar in Beita earlier in the year. Photo by Rick Reinhard.

Against this backdrop of rapid change, MERIP remained steadfast to purpose and politics. It highlighted structural conditions and fine-tuned its analyses of the tight connection between imperial and capital interests, including how the Intifada might, or might not, disrupt them. It never shied away from examining Zionism’s logic of domination and its contradictions, both internal to Israeli society and toward Palestinians. Middle East Report offered a platform for anti-Zionist writers and organizers ostracized and hounded from every other media outlet. Ellen Cantarow wrote about the Zionism in feminist circles and the response of anti-Zionist feminists.

While political economy was still central to MERIP’s analyses, editors were attentive to cultural production and in particular its resonances. And despite its decidedly DIY aesthetic, it often featured the work of artists and graphic designers on its front covers, most notably Kamal Boullata, renowned Palestinian calligrapher, painter and designer (who also designed MERIP’s logos). The photography within the pages of Middle East Report—especially by J.C. Tordai, George Azar and Rick Reinhard—provided additional powerful perspectives on the uprising and reflected the crucial role of imagery in galvanizing support for it. Books on the Intifada were reviewed, as well as films and documentaries. Elizabeth Warnock Fernea wrote on German film productions during this period as they folded Palestine into a study of human suffering, and Joel Beinin wrote on the rise of “peace project” documentaries. Mahmoud Darwish and Taha Muhammad ‘Ali’s poetry was in MERIP’s pages, Ammiel Alcalay contributed literary musings from Jerusalem, and there were translated excerpts from Sahar Khalifeh’s reflections on her home in Nablus. Scholars were given space to reflect on their work, consider their practices and their possible harms. In 1991, Rosemary Sayigh wrote about the complications that arise from the methods of participant-observation and formal interviews for data collection and the compilation of ethnographies through the example of her frequent visits to the women in Wadi Zayna, a set of tenements housing Palestinians in Lebanon. Joost Hilterman sounded the alarm on the insidious role of Israeli journalism in sowing discord, mistrust of the underground Intifada leadership and planting disinformation among Palestinians.

It was to Palestinians that MERIP immediately turned in the aftermath of the 1993 Oslo Accords, dedicating an entire issue, “After Oslo,” to interviews with Palestinian political figures, organizers and scholars. Moreover, they were the primary authors of MERIP’s intensely informative, succinctly written studies of the structures of Palestinian society. Rita Giacaman broke ground in her study of health and its structural determinants. Rema Hammami troubled romanticization of the Intifada with a study of one of the consequences of its decaying organizational discipline to women’s rights.

Throughout this coverage, Palestinians were not only accorded weight as experts of themselves, but as writers giving form to thinking on the broader geostrategic and regional dynamics underlying social and political crises, intensifying authoritarian suffocation in the region and unipolar US hegemony. Just as Palestine is always a MERIP issue, Palestinians remain editorial equals in every issue. In this way it embodied the ethos of this generation of struggle, one that refused the orders of elite powers, charted its own unified path and brought friends along with them. Often poor, mostly young, they kindled a rebellion for freedom whose embers may fade, but it is only so long before another generation ignites it once again.

[Mezna Qato is a research fellow at Newnham College, University of Cambridge, and a former member of the editorial committee at MERIP.]