The Mahshahr petrochemical plant in Khuzestan province. Raheb Homavandi/Reuters

Election news distracted attention from the strikes during their first few days but as the strike wave expanded to new oil and petrochemical refineries and regions, a range of social and political groups took notice. The strikes, due to their size, geographical spread and relative organizational strength, have acquired a political edge. Moreover, their grievances and demands are resonating with large sections of the working population and reviving political memories of oil workers’ special role in the historical events around the Iranian revolution of 1978–1979. Most crucially, although smaller than the protests in January 2018 and November 2019 that resulted from spontaneous mobilization around a national issue, the reach of the recent oil strikes was facilitated by national coordination.

The dynamics of this summer’s oil strikes are remarkable for at least four reasons. First, this wave of protest by contract and temporary workers shows how they have learned from their previous struggles and accumulated experience in pursuing their demands. One estimate from 2011 puts the number of official workers in the oil industry at 90,000 and informal workers at 160,000 (or 64 percent of the total), while another estimate indicates that contract workers make up 75 percent of the workforce.[1] Although there are no official figures of the number of strikers, an estimated 10,000 workers initially joined the strikes, which is unprecedented since the mass oil strikes in late 1978. A significant number of contract workers have accumulated experiences that allow them to learn from previous struggles, to organize strikes more effectively and to sustain them over a longer period. This advantage is partly a result of the relative continuity in labor activism in the oil industry. Last year, for instance, a similar strike emerged among contract workers, and protests have occurred in the oil sector almost annually in the last few years. The nature of the petroleum industry has also facilitated the learning process among oil workers, as relatively large concentrations of workers have been brought together in remote places like Asaluyeh in Bushehr province to construct new facilities.

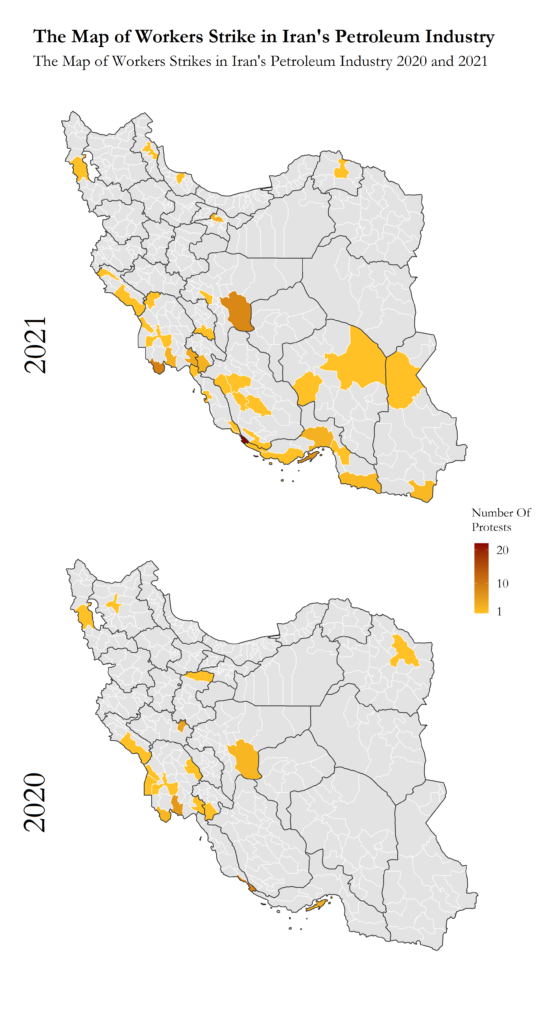

Figure 1. The sources of the raw data for these maps are news articles published in Hrana, Akhbar-e Rooz, and Radio Zamaneh. The 2020 map covers strikes reported from August 1 to September 6, 2020, and the 20201 map covers strikes from June 19 to August 2, 2021.

Second, like last year, temporary workers have formed a committee for coordinating this wave of strikes across various sites in the petroleum industry. As illustrated by Figure 1, the geographic spread of the current strike wave is impressive, involving 102 factories and refineries and 39 counties from June 19 to July 11. This wave has already spread further than the one that occurred in August 2020, which spanned 42 sites in 17 counties during about two months.

The committee is particularly important because the petroleum industry is a highly securitized and surveilled sector, and the state represses independent labor organizations. Nevertheless, contract workers in the petroleum industry have formed autonomous labor organizations through inventive means such as creating a coordinating umbrella organization and holding local gatherings. In some cases, the workers invite authorities to present demands at their meetings rather than send labor representatives to the authorities. These meetings are important for sustaining the protests but also for cultivating a radical democratic culture from the bottom up.

Third, thanks to this organizational strength, the strikes are coordinated across the different localities. During the last several years, numerous protests have occurred monthly. Yet, despite their large numbers and similar demands, those protests were often independent from each other. Occasionally, teachers, truck drivers or retirees coordinated protests on the same day across different cities but usually such protests did not last long. The coordination and resulting continuity of this summer’s strikes can be compared to the demonstrations that broke out about three weeks earlier in the province of Khuzestan on July 15 to protest poor water quality. Because of their intensity and location in urban spaces, the protests in Khuzestan gained much more attention in the media and among public opinion than the oil strikes. The water protests did not last more than ten days as they faced a severe government crackdown. The oil strikes, however, outlasted the water protests and have entered their ninth week.

A fourth remarkable characteristic of the strikes is the high level of visible solidarity. Initially, formal workers in the oil industry declared their support and solidarity with the temporary workers. As they received more attention in the news, other social and political groups also released statements in support of the strike wave. Groups that have announced their support for the demands of the striking workers include steel workers in Ahvaz, the Syndicate of Workers of Tehran and Suburbs Bus Company, the Council of Retirees, the Syndicate of Haft-Tappeh Sugarcane Workers, the association of teachers from Eslam-Shahr and Tehran, a group of lawyers and different political opposition groups inside the country and among the exiled diaspora. Trade union organizations in Sweden, Canada and France have also declared their support. While protests by workers and other social groups have been frequent over the last several years, such a high level of social and political support is unprecedented. For example, when oil workers waged their strike last year at the same time that other groups such as retirees and teachers were organizing their strikes, the different groups did not connect, and the current level of social support now experienced by the oil workers was not present.

Workers Push Back Against Authoritarian Neoliberalism

Due to their size, reach and dynamics, the oil strikes have generated much political attention, from both the Iranian political elite and its opposition. The Ministry of Oil declared that the demands of the temporary workers are outside of its jurisdiction and should be addressed to the contracting companies. President Hassan Rouhani also said that the problem of contract workers “has nothing to do with the oil industry.” Many Iranian officials, particularly at the regional and local level, have sympathized with the striking contract workers while blaming their bad conditions on greedy contractors. On the side of the opposition, from the left to the right, inside or outside the country, support for the oil strikes has been universal. Among oppositional figures and organizations on the right, the poor working conditions are usually blamed on mismanagement, cronyism and corruption. Without a doubt, these factors play a role. In the petroleum industry, for instance, contracts are often given to companies connected to the Revolutionary Guards or charity organizations, although there are also hundreds of private companies operating in this sector.[2] The narrative of both the state and the opposition ignores the extent to which the plight of contract workers is connected to systemic global forces that have shaped policy choices in Iran and elsewhere.

As a result, Iran has witnessed the emergence of a form of neoliberalism that is not unique but is a manifestation of its position within the global economic order. Although independent labor organizations are banned, and protests have been met with repressive measures—factors that make this neoliberalism authoritarian, like Iran’s state-society relations at large—neoliberalism in Iran is marked by hybridity and periods of opening and closure.[4] As a result, there are still functioning organizations, such as the state-approved Islamic labor councils and associations as well as a plethora of smaller independent unions, that even with all their limitations have translated pressures from below up to the state. This hybridity also extends to the neoliberal policies that are shaped by state intervention in the economy and a web of social policies such as subsidies and insurances.

Oil workers are pushing back against the Iranian state’s authoritarian neoliberalism when they articulate their grievances. In their first statement, the striking temporary workers demanded higher wages, a minimum monthly wage of $480 (120 million rials), timely payments and permanent rather than temporary contracts. They also objected to hazardous working conditions, called for stronger safety measures and demanded ten days off for every 20 working days. Finally, workers demanded the end of punitive measures against their activities and emphasized their right to form autonomous organizations and to freely assemble.

The State Response to Increasing Protests

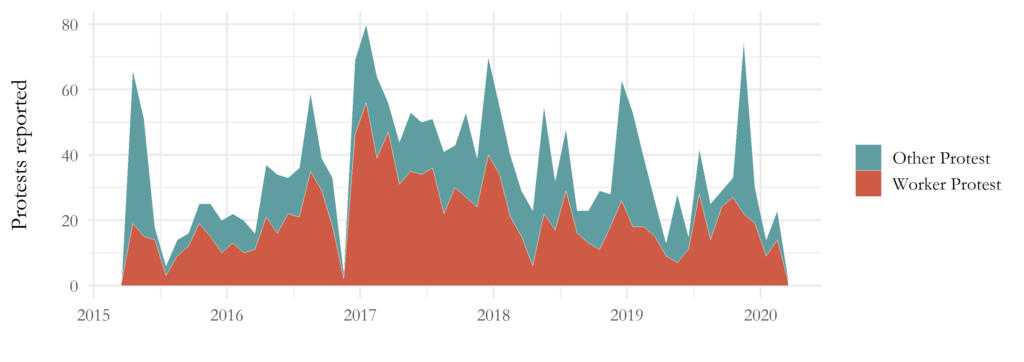

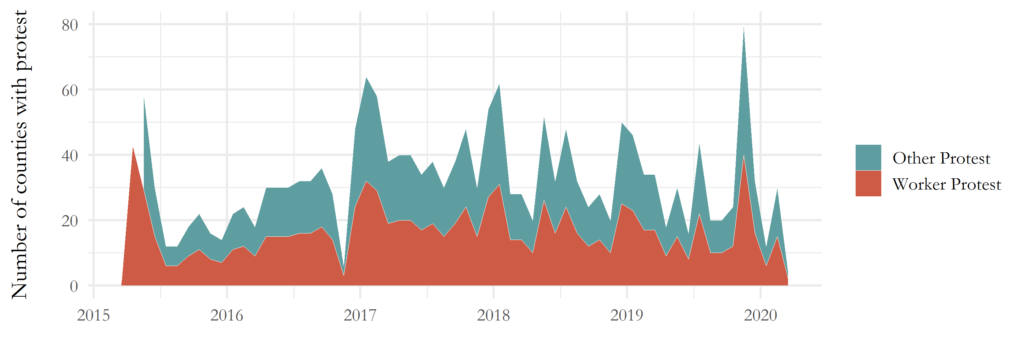

The post-revolutionary populist social contract—through which parts of the working class and the urban poor were incorporated into the socio-political system of the Islamic Republic—is unraveling. With worsening economic conditions due to corruption, domestic policies and US sanctions, along with the weakening of political and social groups and institutions that transmitted social pressures to the top, there has been a steady rise in the number of protests with increasingly radical demands. The accumulation of political and socio-economic crises in Iran, including failures in handling the COVID-19 pandemic, is undermining the efficacy and responsiveness of the political establishment and its institutions, while the expansion of privatization and labor outsourcing has resulted in ongoing strikes and protests by workers in various economic sectors. Figure 2 shows the total number of protests by blue-collar workers, such as workers in the industrial and construction sectors, and other protests organized by professionals, such as nurses or teachers, retirees, the self-employed and unemployed, as well as actions by citizens protesting non-workplace issues such as ecological degradation, subsidy cuts or the entirety of the Islamic Republic. The figures are per month from March 2015 to March 2020 and are based on Iran’s Labor National News Agency (ILNA) reporting in which the word “worker” has been used, generally applied to blue-collar workers. As Figure 2 shows, blue-collar workers’ protests account for a large proportion of the total protests in Iran. On average, ILNA has reported about 36 protests of all sorts and 21 blue-collar workers’ protests per month. There have been 2,183 protests (427 per year) total for this period; blue-collar workers’ protests make up 57 percent. In terms of their geographic spread, on average about 16.5 counties had a reported protest per month, out of which 11.4 (69 percent) had a blue-collar worker protest. For the whole five-year period, 165 out of a total of 429 counties have had at least one reported protest. Out of these 165 counties, 126 (76 percent) had at least one blue-collar workers’ protest. [Figure 3]

Figure 2. Monthly protests reported in ILNA.

Figure 3. Monthly number of counties with protest reported in ILNA.

Protests are not only more prevalent, but the state has also demonstrated its ability to intervene in them through existing institutions, such as local city and village councils and the Islamic labor councils and associations. Although the effectiveness of the labor councils has weakened, their numbers have increased from about 2,000 in 1990 to more than 5,000 in 2010, reaching more than 10,000 in 2018.[5] State officials often use these and other institutions to channel the protests of workers through orderly negotiations, including in the recent oil strikes. In addition, the government and their contractors have intimidated workers with layoffs, blacklisting and surveillance by security forces and created divisions among workers by initiating negotiations, encouraging the establishment and involvement of Islamic labor councils and making concessions.

When the contract workers started their strikes on June 19, they hoped the official workers of the petroleum industry would join them. The official workers had staged their own protests in Tehran, Ahwaz and Asaluyeh on May 26 to demand better employment conditions and had announced they would resume their protests on June 30 if the government did not fulfill their demands. After the contract workers started their strike, however, government officials moved quickly to negotiate with the official workers: Parliament’s energy commission started investigating the issue and President Rouhani declared that the government would fix their wages. The Islamic labor councils of permanent workers in southern Iran also increased their activities, such as petitioning parliament and the head of the judiciary, Ebrahim Raisi (who was elected president in June).

At the same time, officials at the local level have been actively organizing meetings with the striking contract workers, promising to resolve their problems and to pressure the authorities in Tehran. Although state officials had pushed even the Islamic labor councils out of the oil industry in the last two decades, they started to bring them back in response to the recent oil strikes. Some officials have floated the idea of reorganizing the industrial relations office controlled by the employers in Asaluyeh into an Islamic labor council to provide workers an official channel for negotiations. The independent Council for Organizing Protests of Contract Oil Workers is opposing these initiatives, however, presenting itself as the only genuine organization of contract workers. The fourth statement by the striking workers says:

We declare that assembling Islamic councils or any other organization as “independent” workers organizations by the government is an action against the workers and is not the proper response to us. The record of Islamic councils and other puppet organizations like them are clear. These organizations were always a tool to control workers and to serve employers. Aren’t the 40,000 security personnel in the oil industry enough, that now you also want to add Islamic councils?[6]

While these attempts to bring Islamic councils back into the oil industry demonstrate the importance of intermediary organizations between the state and workers, the routinization of protests is permanently undermined by the unwillingness and incapacity of state officials to institutionalize labor protests and to make significant concessions. This situation creates a dynamic in which labor protests continuously appear outside of the official channels and transgress the political limits of the system. It also creates serious divisions among labor activists, due to their different views on strategies and tactics. The Council for Organizing Protests of Contract Oil Workers, for instance, has pursued a radical approach that calls on workers to continue their strikes, organize through assemblies, hold protest gatherings until all their demands are met and to raise political demands. On the other hand, however, another group—the Piping and Project Group of Iran—that organized the contract workers’ strikes last year, has emphasized socio-economic demands and steered away from more political demands to lower the risk of repression and to increase the willingness of more workers to join.

But how should all these developments be interpreted? Are protests becoming routinized within the existing political system, or are they, as some oppositional media and political parties believe, a prelude to a bigger uprising? Framing the strikes in this dichotomous manner runs the risk of ignoring the demands and grievances of the workers and the variety of opinions among them. Protests have become a common practice in Iranian society, but government has been pushing back and trying to restrict protest activities by outlawing independent unions.

The protest movement against the monarchy broke out in urban areas from January to summer of 1978. Inspired by the street protests, different workers and state employees also went on strike during the fall of 1978. Among these strikes the labor actions by the workers and employees of the National Iranian Oil Company were key as they halted the country’s oil production and distribution. The participation of the formal employees was crucial to these strikes, and it was only in the last stages that the process workers in the refineries joined in. Although the number of contract workers was not as high as today, those workers were also striking with the demand to be officially employed by the oil industry. The divisions among blue and white-collar workers and official and contract workers were a serious obstacle in 1978 as they are today, but they were overcome in the context of a revolutionary movement that radicalized the workplace.

The situation is very different today as the official oil workers have not staged strikes, the contract workers have mainly socio-economic demands and an organized mass revolutionary movement is absent. Political and economic crisis in Iran has obviously influenced the current strikes, and the protests could involve the official workers and spread to other sectors as well in the future. It is, therefore, important to appreciate the contingent and fluid nature of these strikes, rather than conceiving them as repetitions of the past or project on them particular political objectives in an act of wishful thinking.

While outside observers of different political leanings have been contemplating the possible consequences of the strikes, the eleventh statement by the Coordinating Committee presents one of the more important assessments of the achievements of their ongoing campaign. The statement mentions concessions already offered by contractors about increasing wages and awareness raised about the poor quality of food for contract workers. Furthermore, the statement points out how the strikes have succeeded somewhat in breaking the heavily securitized atmosphere in the oil industry. Finally, the statement mentions the emerging organizational power of the workers as their main achievement so far: “Most importantly, we have experienced our great power as workers, and this puts us in a stronger position to pursue our demands. Particularly, we have succeeded in forming an organizing council to be the true representative of the workers.”[7]

The oil strikes are representative of an important trend in Iran—the growth of labor protests. It is too soon to draw any definitive conclusion about their outcome, but as the workers themselves indicate, they might contribute to the formation of new workers’ organizations. Beyond the labor movement, the convergence of labor protest and broader political mobilization in 1978–1979 suggest that these two ongoing trends of protest in the country can inform and build on each other.

[Mohammad Ali Kadivar is assistant professor of sociology and international studies at Boston College. Peyman Jafari is a postdoctoral research associate at Princeton University. Mehdi Hoseini is a prospective student of sociology at Boston College. Saber Khani is a PhD student of sociology at Boston College.]

Endnotes

[1] Mohammad Maljoo, “Temporalization of Labor Force Contracts in the Oil Industry After the War,” Negah-e No Quarterly 105 (2015). [Persian]

[2] Frederic M Wehrey et al., The Rise of the Pasdaran: Assessing the Domestic Roles of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (Santa Monica, CA: RAND National Defense Research Institute, 2009).

[3] Maljoo “Temporalization of Labor Force Contracts in the Oil Industry After the War.”

[4] Peyman Jafari, “Impasse in Iran: Workers versus Authoritarian Neoliberalism,” If Not Us, Who? Workers Worldwide against Authoritarianism, Fascism and Dictatorship (Hamburg: VSA, 2021).

[5] Peyman Jafari, “Impasse in Iran: Workers versus Authoritarian Neoliberalism,” p. 145.

[6] The Organizing Committee of the Protests by Oil Contract Workers, “We Don’t Want Islamic Councils; The Response of Oil Temporary Workers to Raisi’s Proposal,” Akhbar-e Rouz, July 3, 2021. [Persian]

[7] The Organizing Committee of the Protests by Oil Contract Workers, “The 11th Statement; Where Are We in Our Strikes?” The Organizing Committee for The Strike of the Oil Contract Workers Telegram, July 25, 2021. [Persian]