Narratives of 'the Oppressed'—The Dialectic of Resistance Behind the Axis

Since its formation, the Axis of Resistance has embodied a defiant stance against imperialism and Zionism.

The phrase itself first circulated in the English-language media, in the early 2000s—a response to then-President George W. Bush’s ominous talk of the “axis of evil.” By 2010, at the latest, the coalition had adopted the phrase as its self-designation. The Axis has served a strategic purpose for Iran, functioning as a tool of deterrence in the wake of the 2003 Iraq invasion. By uniting regional actors in opposition to Israeli and US dominance, Iran sought to counterbalance the threat of military intervention. But this once-cohesive alliance is at a moment of uncertainty.

Contrary to the assumption that Israel’s war in Gaza, undertaken with full US backing, would strengthen the Axis of Resistance, it has partially unraveled in the face of war and wider regional aggression. Syria’s departure from the Axis after the fall of Bashar al-Asad, in December 2024, along with growing domestic challenges to Iran’s foreign policy, raise questions about its future unity. Hizballah, embroiled in an enduring conflict with Israel, has been significantly weakened. Hamas has faced 15 months of ongoing Israeli efforts at its eradication, while other movements within the Axis contend with their own internal and external challenges.

Through its peak, the Axis of Resistance has long been united by a shared binary logic that framed the world as divided between the oppressed and the oppressors. At the heart of this framework is Palestine, where Palestinians serve as the archetype of the oppressed and their liberation as the coalition’s central moral cause. This narrative weaves diverse struggles—political, economic and spiritual—into a unified tale of defiance and justice.

Most actors within the Axis, frame their resistance not as conventional statecraft but as part of a broader moral struggle. Under Iran’s leadership, these struggles transcend geography and lived realities, binding disparate movements to a shared vision. Recently, the spokesman of the Yemeni Ansar Allah (or Houthi movement), Muhammad Abdulsalam, described the Palestinian cause as Yemen's main concern because, in his opinion, true peace can only be achieved by defeating the “Zionist entity.” This framing divides the world into two opposing forces: US imperialism and its Zionist offshoot, as the oppressors, and Palestine as the ultimate symbol of resistance.

The revolutionary discourse that unifies the Axis predates its actual formulation in the 2000s.

Ayatollah Khomeini’s declaration that “Islam belongs to the oppressed, not the oppressors,” encapsulated a vision that transcended Iran’s borders, offering a moral framework for resistance rooted in Islamic tradition and modern anti-colonial thought.[1] Shaped by Quranic principles, as well as thinkers like Ali Shariati and Morteza Motahhari, this vision framed the Iranian Revolution as more than a quest for political sovereignty. It was a call to arms for the oppressed everywhere. By invoking the concept of mostazafin, or the oppressed, Khomeini transformed Iran’s revolution into a universal narrative of justice and defiance, aligning it with global struggles against colonialism and disenfranchisement.

By invoking the concept of mostazafin, or the oppressed, Khomeini transformed Iran’s revolution into a universal narrative of justice and defiance, aligning it with global struggles against colonialism and disenfranchisement.

This pan-Islamic framing had its first major test during the Iran-Iraq War (1980–88). While the conflict is often revisited through the lens of sectarian and ethnic divides—Shi'a versus Sunni, Persian versus Arab—Iran’s rhetoric sought to transcend these boundaries. The war was framed not as a sectarian or national conflict but as a moral struggle of justice against tyranny. Official discourse portrayed Saddam Hussein’s regime as a small gang of infidels serving imperialist interests, while Iran positioned itself as the vanguard of Islamic resistance. Though this narrative failed to resonate with most Iraqis, it revealed the potential of Iran’s broader resistance narrative. This ability to frame conflicts as part of a global struggle against oppression would later underpin Iran’s leadership within the Axis of Resistance and demonstrate the adaptability of this narrative to extend beyond its borders.

The binary logic and vision of dividing the world into oppressed (mostazafin) and oppressors (mostakberin) found resonance across the region. In 1985, Hizballah explicitly adopted this narrative, embedding it within its local resistance to Israeli occupation in Lebanon. Through its Open Letter to the Oppressed in Lebanon and the World, Hizballah reimagined its struggle as part of a global fight against imperialism.[2] By invoking the plight of the oppressed, Hizballah not only aligned itself with Iran’s conceptualization of the mostazafin but also amplified the narrative’s regional reach.

Khomeini’s vision, which he had partly adopted from leftist thinkers and organizations in order to respond to their demands, resonated powerfully because it transcended the material deprivation on which left-wing discourses remained fixated. Championing the plight of the mostazafin was not merely about economic hardship but about the deeper human struggle for recognition. In Hegelian terms, this was a fight for identity and dignity—not just material gain—where true freedom emerges through the willingness to risk one’s life to defy the oppressor. This dynamic is central to the Iranian narrative, which frames the struggle as both a fight for survival and a quest for moral and spiritual recognition.

In this conceptualization, the mostazafin seek to reclaim their right to exist as well as their right to be seen and recognized. Martyrdom is a key component of this fight—not only because self-sacrifice is central to asymmetric resistancet—but also because martyrdom is the foundational myth of Shi'a Islam. In embracing the potential of self-sacrifice, the oppressed can turn martyrdom into a powerful act of defiance, affirming that they have nothing to lose and everything to gain in this world or the next. This framing expands the mostazafin narrative, transforming it from one rooted in material struggle into a profound moral and spiritual battle that unites those seeking justice across different levels of oppression and identity.

As the mostazafin narrative evolved, it required a symbol that could unify and amplify its message across ethnic, geopolitical and religious divides. This symbol was Palestine. Initially, the connection to Palestine was political: Iranian revolutionaries had trained in PLO camps, while the Shah maintained discrete, but close ties with the Israeli government. Palestine transcended its origins, however, to become the embodiment of the mostazafin’s collective plight—a visceral and universally recognizable example of oppression. The occupation of Palestine and the displacement of its people offered a stark and undeniable image of the struggle for justice.

For Khomeini and his successors, the choice of Palestine as the centerpiece of the mostazafin narrative was also strategic.

For Khomeini and his successors, the choice of Palestine as the centerpiece of the mostazafin narrative was also strategic. The repeated failures of Arab regimes, from the humiliation of the 1967 War to the compromises of the Camp David Accords in 1978, left a void in leadership over the Palestinian cause. By championing Palestine, Iran, in the wake of the 1979 revolution, positioned itself as the defender of the oppressed while simultaneously challenging Arab states that had abandoned the rhetoric of resistance.

Two key elements further bolster Palestine’s centrality to the narrative of resistance. First, the territory of Palestine—particularly Jerusalem and the Al-Aqsa Mosque—operates as a universal symbol of justice, belonging not just to Palestinians but to all Muslims since it is considered inalienable religious endowment land (waqf).[3] This framing fosters a collective identification with Palestine across sectarian and national divides, positioning it as a cause that transcends boundaries. Second, Israel, framed as both a US-backed imperialist and explicitly Jewish state, epitomizes oppression in regional narratives. This portrayal (which in Iranian media and elsewhere can often be tied to antisemitic tropes) simplifies the construction of the enemy and strips Israel of legitimacy. By framing the struggle for Palestine as a fight against occupation and dispossession, Iran casts resistance as a moral imperative, uniting diverse actors under a shared vision of justice and defiance.

The framework of resistance against oppression continues to shape the rhetoric and strategies of the various actors in the Axis, though for many, explicit references to the mostazafin have been less prominent—or absent entirely. Hizballah has flirted with the term since its founding, partly due to its ideological and organizational proximity to Iran. The term, however, is not as salient within Hamas or Palestine Islamic Jihad discourses, perhaps because the lived realities of occupation, displacement and conflict are not best framed by a concept forged in the days of the Iranian Revolution. Among others, like state leadership in Iran and—until recently—Syria, Palestine serves primarily as a mobilizing force, one capable of harnessing extraordinary power as a unifying narrative far removed from the day-to-day experiences in the West Bank and Gaza. For Yemen’s Ansar Allah, the discourse of the oppressed and its amalgamation with Palestine has been woven into its ideological core. The movement has adopted the mostazafin narrative to align its local struggle with a transnational cause. Examining this case provides insight into the ongoing influence and adaptation of Iran’s revolutionary narrative as it moves to other contexts.

Also in this Issue: Helen Lackner, 'On the Houthi Movement's Roots, Governance and Resistance.'

If Iran’s mostazafin narrative emerged from the fires of revolution, Ansar Allah’s adoption of it was born out of decades of marginalization. Known more commonly as the Houthis, after the family name of its key leaders, this Zaydi movement originally responded to the growing influence of Salafi ideology in Yemen. What began as a local effort to preserve the religious and cultural identity of the Zaydi sada families and resist the Yemeni government’s encroachment on their political privileges gradually transformed into a broader political movement. Over time, Ansar Allah has positioned itself less as a sectarian group and more as a pan-Islamic force of resistance.

Central to this evolution was Ansar Allah’s embrace of Palestine, a cause that allows the movement to transcend its narrow sectarian roots and align with the larger narrative of resistance against global oppression. Given its Zaydi identity, which places Ansar Allah outside both Sunni and Twelver Shi'a orthodoxy, Palestine serves as a potent tool for political legitimacy.

Moreover, given Yemen’s long history of solidarity with Palestine, championing the oppressed in Palestine presents an opportunity for Ansar Allah to pivot away from addressing local concerns—from skepticism of the sada’s claim to power to dissatisfaction with the nature of their governance—allowing the movement to gain legitimacy within Yemen and internationally. Their affiliation with a transnational network united under the banner of the mostazafin opens doors in alliance politics: Through membership in the Axis of Resistance, Ansar Allah gains international recognition and has access to financial and material resources that would otherwise be denied to them.

Iran’s influence is unmistakable in both the rhetoric and actions of Ansar Allah. Adopting the mostazafin/mostakberin dichotomy championed by Iran, Ansar Allah casts Yemen’s internationally recognized government as a puppet of imperialist forces, with Saudi Arabia as the enforcer of oppression. This revolutionary rhetoric—echoed in slogans like “Death to America, Death to Israel, Curse on the Jews”—powerfully mirrors Iran’s ideological stance (though the latter part of the phrase is notably absent in the Iranian context, reflecting Ansar Allah’s local adaptation). Iran’s influence is further evident in the structural parallels between groups like Ansar Allah and Hizballah and the Iranian Revolutionary Guards, highlighting a shared organizational and strategic framework.

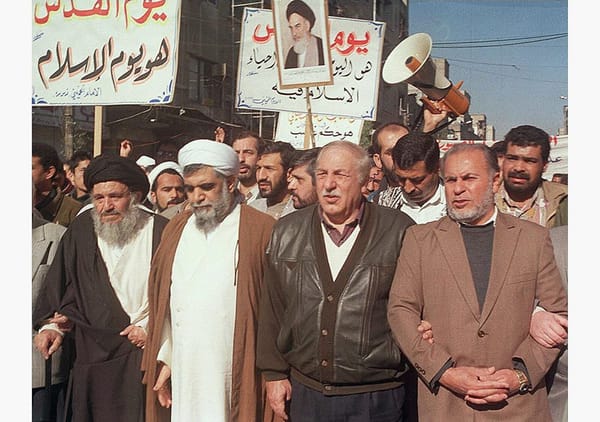

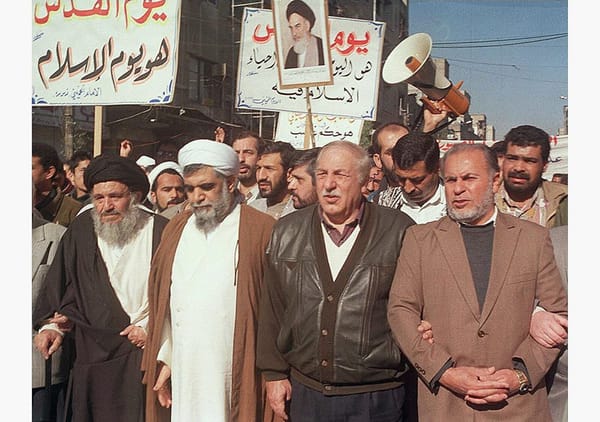

Likewise, the introduction of Iran's Ashura Memorial Day and “Al-Quds International Day” in Yemen attest to this influence. But the real strength of this narrative lies in Ansar Allah’s self-presentation. On its media platform, Al-Masirah, the Palestinian cause is front and center. Ansar Allah uses the term mustada‘fin—the Arabic equivalent of the Persian mostazafin—and gestures toward the idea of mostakberin (the arrogant oppressors) by referencing quwa al-istikbar ("powers of pride").

Ansar Allah is continuing this rhetoric amid the latest developments in Syria and Iran's retreat from the country. In January 2025, Al-Masirah reported on a march by militiamen in which support for Palestine was described as both a religious and national duty, framed in the binary world-view of oppressed and oppressors:

mustada‘fin[4]

The strength and resilience of the resistance narrative for the Axis lie in its remarkable adaptability, allowing it to resonate across vastly different contexts over time. The fundamental dichotomy between oppressors and oppressed has proven flexible, enabling Iran, Ansar Allah and other actors to tailor it to their specific needs while preserving its ideological core.

Since October 7, 2023, the centrality of Palestine to this narrative has only deepened...But October 7 has also revealed the limits...

Since October 7, 2023, the centrality of Palestine to this narrative has only deepened. With its vocal support of Palestinian resistance, Iranian leadership can continue positioning the state as the defender of the oppressed while challenging Arab regimes and asserting authority in the region.

But October 7 has also revealed the limits of this narrative: The Iranian government’s calculation not to join Hamas in an open war against Israel and its inability to support its allies within the Axis with more vigor—personified in the ousting of Bashar al-Asad in Syria and the assassinations of Hizballah's Hassan Nasrallah and Hamas's Ismail Haniyeh—has exposed the fragility of Iran’s claims to moral and strategic leadership on behalf of the oppressed. While these tensions are not all new—they were prevalent in Iran’s intervention to support Asad’s regime during the Syrian civil war and in the “Woman, Life, Freedom” uprisings in 2022—the country’s unwillingness to sacrifice its own existence, and its recognition by many across the region as a hegemon and oppressor in its own right, points to faultiness permeating the narrative of resistance.

The dialectic of resistance, built on defiance and sacrifice, might struggle to endure when those in power cannot support the principles they championed. On the other hand, the framework of resistance, rooted in justice and defiance, continues to resonate with movements across the region.

Read the previous article.

Read the next article.

This article appears in MER issue 313 “Resistance—The Axis and Beyond.”

[Olmo Gölz is a senior lecturer in Islamic and Iranian Studies in the department for Oriental Studies, University of Freiburg. Ruth Vollmer is a graduate student in Islamic and Arab World Studies at the department for Oriental Studies, University of Freiburg.]

[1] Ervand Abrahamian, Khomeinism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), p. 31.

[2] Joseph Elie Alagha, Hizbullah's Documents: From the 1985 Open Letter to the 2009 Manifesto (Amsterdam: Pallas Publications, 2011), p. 41.

[3] Gudrun Krämer, A History of Palestine: From the Ottoman Conquest to the Founding of the State of Israel (Princeton University Press, 2008), p. 32.

[4] “Sana'a.. Receiving a Procession in the Sa'fan District,” Al-Masirah, January 2025.

[5] Kevin L. Schwartz and Olmo Gölz, “Visual Propaganda at a Crossroads: New Techniques at Iran's Vali Asr Billboard,” Visual Studies 36/3-4 (2021), pp. 476–90.