Joseph (Joe) Stork—A Tribute

For much of the first 25 years of his professional life, Joe Stork and MERIP (the Middle East Research and Information Project) were virtual synonyms.

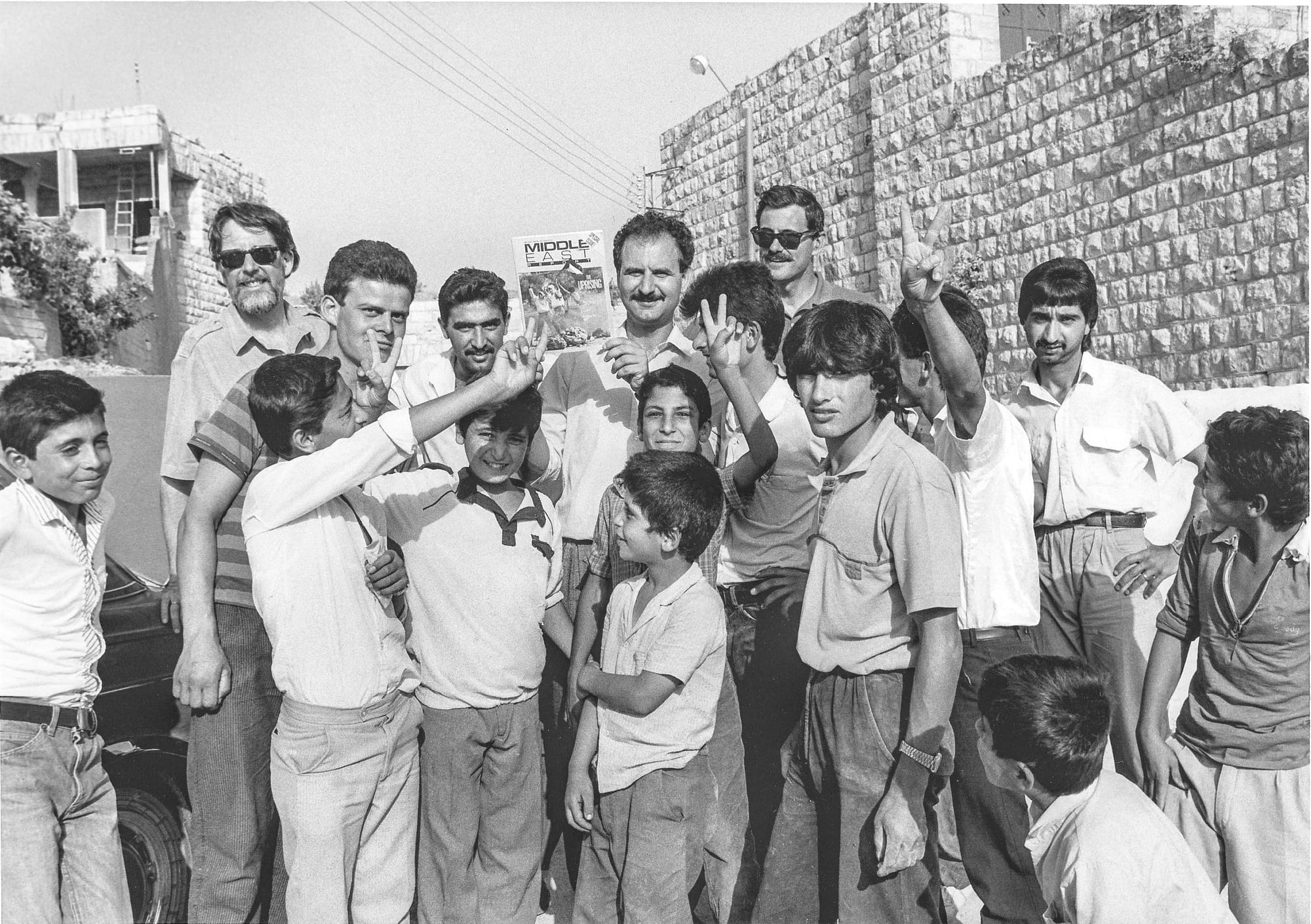

He co-founded the organization in 1970 and dedicated himself to its development until he stepped down in 1995. He shaped MERIP as a journal and as a community, serving as Editor of what came to be Middle East Report (MER) and running the MERIP office in Washington, DC. Its remarkable history of longevity, journalistic quality, comradeship and adherence to principle owes much to Joe. He was the warp and the weft of MERIP.

Joe first engaged with the Middle East region as a member of the inaugural contingent of Peace Corps volunteers in 1964. Like many idealistic college graduates of the time, he hoped to make a positive difference in the US global reach. He was sent to Tokay, Turkey, where he spent a formative two years teaching English. After his return, he studied at Columbia University, earning an MA in International Relations and Middle East Studies. He also connected with the Committee of Returned Volunteers (CRV): a group of people who had served in the Peace Corps or in other volunteer positions across Asia, Africa and Latin America and had developed an anti-imperialist critique of US foreign policy.

In 1970, he published an article in the first issue of the CRV’s magazine, Two…Three…Many, titled “Palestine is a Revolution.” In the piece, Joe confronted the silence of US peace activists when it came to Palestine. He provided a brief history of the Palestinian national movement and shared his own observations of its activities on the ground in Lebanon and Jordan. His analysis placed Israel and Zionism in the context of western imperialism and argued that US and Israeli interests converged in their attacks on movements challenging US hegemony in the region. In brief, he offered a vision of the Palestinian liberation struggle as part of a global anti-imperialist movement. It is hard to overstate how revelatory this analysis was for almost everyone on the US Left. Joe had started out on his path to call their attention to Palestine and the Middle East region.

In brief, he offered a vision of the Palestinian liberation struggle as part of a global anti-imperialist movement.

Around the same time, in October of 1970, Joe and six others with shared interests in the Middle East and similar backgrounds of standing against the US war in Indochina met in a cabin in New Hampshire. United by the desire to confront the avoidance of Palestine on the part of the US Left, they decided to found MERIP. As Peter Johnson, one of the original seven, observed: “When we started, the words ‘Palestine’ and ‘Palestinian’ could hardly be used in political discourse. And look where we are today—Joe, and MERIP, certainly had something important to do with that change.” It soon became clear to the group that MERIP needed to look at the broader context, to take up the task of analyzing US policy and strategies in the Middle East region as a whole, to provide the research and information that would encourage activists to work toward changing US policy.

MERIP began in 1970, as an occasional two-page newsletter. By 1973 it was being produced on a regular basis by the MERIP collective, comprised of two “clusters” of people in Washington and Boston, who took turns producing the magazine. Periodically, they met together in either city, meetings playfully called “intergalactics.” It was at one of these meetings when I first met Joe.

There was a certain level of studied anarchy in those years—the eschewing of hierarchies meant that there was no division of labor. Members of the collective were jacks of all trades: They researched, wrote, edited, typeset, marketed and budgeted for the publication. Joe embraced this model until it became clear that we could not continue to produce a magazine this way. He then led the painful process of rethinking MERIP’s structure and persuading the collective’s members that we would not survive unless we moved in the direction of staff specialization, systematic budgeting and organized fundraising.

After considerable discussion, sometimes heated, MERIP was consolidated in the Washington office in 1975, and Joe took the lead in stabilizing the organization. Joe’s ability to rethink MERIP’s structure and to make tough decisions, as well as his willingness to make personal sacrifices to stick with the project, were central to MERIP’s fortunes over time. As Zach Lockman, former editorial committee member, noted: “Many such initiatives and organizations do not survive the departure of their founder, and it is to Joe's credit that MERIP continued after he moved on and has been able to reinvent itself and survive in a very different environment.”

It is important to note that the reorganization of the staff did not blunt Joe’s egalitarian and inclusive inclinations. Joan Mandell, early staff and long-time editorial committee member, recalls: “It was amazing to me that Joe was by far the most prolific editor and much better connected, but in our office he worked alongside much less experienced staff, dividing labor equitably and collecting the same minimalist salary.” He also took his place in the rotation for cleaning the MERIP offices and the bathroom (although rumor has it that following after him in the schedule was not a prized assignment). Many visitors—contributors with Middle East expertise from all over the country, the Middle East and Europe—came by to meet with him, and he scheduled staff lunches so everyone could gather and exchange views. The people on staff he worked with over the years remained close and loyal friends and were changed by working with him. Esther Merves, a long-time staff member and then close friend until the end of his life, reflected on this impact: “Joe's work at MERIP inspired in me a lifelong interest and commitment to the region.”

Joe was a man of parts. He was a writer of clear and fluid prose and an indefatigable researcher who left no stone unturned. His book, Middle East Oil and the Energy Crisis, published in 1975, was a master work of political economy, linking the rise and expansion of oil production in the region to political developments, chief among them the expansion of US empire. The work proved to be all too prescient when it came to future US interventions—even if the disastrous years that followed have outstripped all predictions.

Joe’s intellectual work put MERIP on the map in those early years. As I look over the books he wrote and edited, and the 100 or so pieces he penned for MERIP over time, I am struck by the breadth of his knowledge—US Middle East policy across the region as well as political and social movements in Egypt, Palestine, Iraq, the Gulf and elsewhere. In addition to his clear-eyed analysis, the causes of justice and equality for the people of the region inflected virtually everything he wrote.

Joe also put his talents as superlative editor, researcher and writer in the service of so many. He mentored, encouraged and whipped many of us into shape. Staff, editorial committee members and contributing writers all learned from him: how to write accessible prose, how to sharpen our analysis, how to cut out the fluff. It was not always easy for academics, in particular, to accept Joe’s notoriously thorough edits, but he always held his ground, and we invariably surrendered ours. As Lisa Hajjar, former intern, staff and editorial committee member, recalls: “Joe was like a wizard with his red pen…. His ability to reshape articles to make them more clear, compelling and ‘MERIP-y’ was magical.” Joe was a teacher, and many of the graduates of his MERIP workshop went on to become key players in universities and other institutions connected to Middle East studies.

MERIP grew and changed over the years, always responding to the key political events of the day but also becoming a forum for academics on the left in Middle East Studies and a resource for the classroom. Through 25 years of evolution, it was Joe who stayed the course and prepared MERIP for the next 25. Jim Paul, who worked in partnership with Joe from 1977 to 1989, observed: “There was one person who held things together and inspired the collective spirit and political commitment … and that was Joe. People came and went but he was the steadying force and the person most committed to the project for the long term.”

Joe had woven together a community of activists and writers from across the country, the region and the globe, who wanted to place their time and their scholarship in the service of justice in the region.

At a party marking the occasion of his stepping down from MERIP after 25 years, Joe insisted in his typical fashion that his work with MERIP over the long years of many challenges had been a privilege, not a sacrifice. He told us how much he relished the people—the staff, the members of the editorial committee, the writers—whom he had been fortunate enough to come to know; how lucky he felt to have been the thread of MERIP while also insisting that it was never an individual achievement. Joe had woven together a community of activists and writers from across the country, the region and the globe, who wanted to place their time and their scholarship in the service of justice in the region. Many found a home in MERIP and they also found each other. As Joel Beinin, former editorial committee member, put it: “MERIP was the constellation that informed a huge proportion of whatever I accomplished, and Joe was the brightest star in the constellation.”

After his time at MERIP, Joe went on to work at Human Rights Watch, where he spent nearly three more decades as advocacy director and then deputy-director of the Middle East and North Africa division. He wrote reports tracking rights abuses in Israel/Palestine, Egypt, Iraq and the Gulf states. He advocated for political prisoners across the region, developing personal loyalties as he grew close to many of them and their families and stood by them year after year. “I mourn a mentor, a teacher and a great friend,” said Nabeel Rajab, president of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights. “Joe was also a close family friend, and during the seven long years I spent in prison, he stayed in contact with my family, offering them comfort and support. His presence, even from afar, gave me hope and strength in those difficult times.” Joe was on the Advisory Board of the Gulf Centre for Human Rights (GCHR) from 2011 up to his death and served as chair from 2019 to 2022.

Joe loved many people and many things: He adored his late wife Priscilla Norris, his compañera of 37 years, his three daughters and his four grandchildren. He celebrated Irish music and often played it as an accomplished musician who had mastered many string instruments and also did vocals. In the 1970s, he played acoustic bass and sang with the Fast Flying Vestibules, an old-time string band of considerable regional reputation. Later, Joe and Frank Haltiwanger formed the Crooked Jack duo, playing American roots and Irish music together in many local venues. Over the years he shared his impeccable taste in music with family and friends by gifting them CDs he compiled, always with a theme that resonated with the receiver. My personal favorite was “Women Do Dylan,” a collection of Dylan covers recorded by various women musicians. He was an avid and erudite reader of English literature, including poetry from the classics to the contemporary.

The house on Delafield Place in Washington, DC that Joe shared with his beloved Priscilla was the site for many, many gatherings over the years. MERIP comrades, activists and scholars connected to the Middle East and North Africa and the wider world of human rights, fellow musicians, members of the far-flung Stork and Norris families and numerous friends came together to eat delicious food, converse, listen to music and relax in each other’s company. Joe and Priscilla, master hosts and weavers that they were, provided the space and the grace that knit and nurtured our community.

Read the previous article.

Read the next article.

This article appears in MER issue 313 “Resistance—The Axis and Beyond.”

[Judith E. Tucker is a former member of the MERIP collective and a professor emeritus in history at Georgetown University.]