Breaking the Fourth Wall—Reading Sadallah Wannous in a Time of Genocide

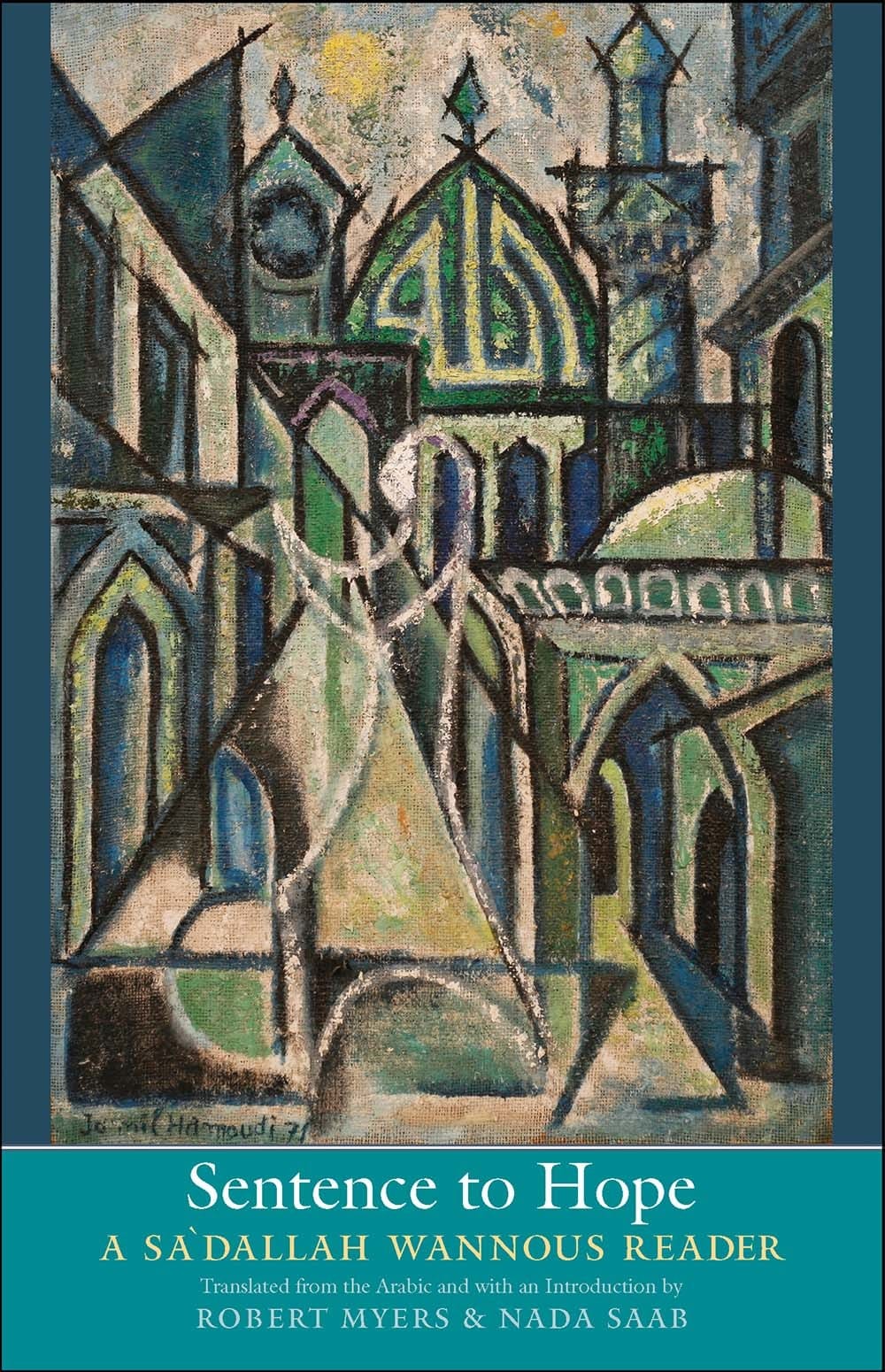

Robert Myers and Nada Saab, Sentence to Hope: A Sa’dallah Wannous Reader, Yale University Press, 2019.

At the end of Sadallah Wannous’ 1970 play, The Adventures of the Mamlouk Jabir’s Head, the action takes an abrupt, dark but entirely predictable turn.

Wannous—a Syrian playwright who was born in 1941 and died in 1997—wrote the play as a story within a story. It begins at a café, where a hakawati (story teller) arrives each night, book in arm, to provide the patrons with an evening of entertainment. Each night, they beg the hakawati for an epic tale, one with a happy ending “about truth triumphing over deception” and “justice overcoming injustice.” The hakawati, however, is adamant: They must hear the stories in chronological order. Currently, they are stuck in “the age of unrest and anarchy” (129). It’s a sentiment that feels familiar in today’s world of doom-scrolling and perpetual crisis.

On the night in question, the tale is of the Mamlouk Jabir, a slave living in medieval Baghdad, plagued by a war between the caliph and an enemy king. (In the stage directions, these figures are to be played by the same actor.) A duplicitous vizier wants to smuggle a letter out of Baghdad to forge an alliance with the enemy king, but the city is under siege, its gates guarded by soldiers. Jabir comes up with an ingenious ploy. He will shave his head, have the message tattooed on it and then grow out his hair. In exchange for smuggling the message out, he will be rewarded handsomely.

But things don’t go according to Jabir’s plan. When the king receives the message, he disposes of the mamlouk’s head and invades Baghdad. Carnage ensues. “They thought doomsday had arrived. Gates to the city were flung open, troops invaded the souks.” According to the stage directions, actors should silently mime the violence as the hakawati narrates: “Grief pervaded every corner, death spread like air. Dozens died without a clue of what was going on around them. Streets were piled with corpses, the wounded, the rubble of crumbling houses” (205).

Reading these lines today, it is hard not to hear echoes of Israel’s genocidal war on Gaza in the apocalyptic description of death and destruction. Wannous wrote Mamlouk Jabir, following an earlier moment of crisis for Palestinians, the Naksa: Israel’s defeat of the Egyptian, Jordanian and Syrian armies in June of 1967, displacement of some 300,000 Palestinians and occupation of the West Bank, East Jerusalem, Gaza, Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights.

At the time of the June War, Wannous was in Paris, where he had moved from Damascus one year earlier to study theater at the Sorbonne. While there, he encountered the work of Bertolt Brecht, who had challenged the conventions of theater by breaking the fourth wall between audience and performer. He also came into contact with other anti-imperialist, Marxist playwrights. Influenced by Brecht, they explored the revolutionary potential of theatrical performance. One of them, Peter Weiss, had staged an influential experimental theatrical production about the Vietnam War in 1966 with the provocative, if lengthy, title: Discourse on the Progress of the Prolonged War of Liberation in Viet Nam and the Events Leading Up to It as Illustration for the Necessity for Armed Resistance against Oppression and on the Attempts of the United States of America to Destroy the Foundations of Revolution.

Wannous’s biography is detailed by Robert Myers and Nada Saab in the introduction to the only English language anthology of his works: Sentence to Hope: A Sa’dallah Wannous Reader (Yale, 2019). The entire volume includes their translation of The Adventures of the Mamlouk Jabir’s Head and three other plays as well as selected writings. It is worth revisiting in full in the context of the war on Gaza, the social movement that has exploded since October 2023 and the reflections it has prompted on the longer history of resistance to US imperial and Israeli violence in the region.

Mamlouk Jabir was the second play Wannous wrote following the Naksa. The first, An Evening’s Entertainment for the Fifth of June, was published in the Arabic literary magazine Muwaqif in 1969 and first performed in Lebanon and Sudan in 1970. An Evening’s Entertainment was a more direct response to the events of the June War and the political circumstances that engendered it. Also a play within a play, it satirized the oppressive Ba’athist state in Syria, featuring a government official for a director who hires a playwright to help stage a propagandic retelling of the war. Throughout the course of the play, actors placed among the audience interrupt the action to critique the dialogue and the director’s spin on events. In one exchange, “a loud, sharp voice is heard in the middle of the auditorium”:

SPECTATORS.

—That’s no way to talk.

—Good God, what kind of evening is this?

DIRECTOR. (He looks toward the audience) Watch your mouth, sir, if you please. You’re not in a café (21).

For Wannous, theater was not just political in the sense that it offered an unapologetic critique of those in power. The theatrical experience could also be politicizing, what he called a “theater of politicization” (122). Wannous recognized that social relations, like theater, tend to follow a script—one in which an individual’s fear of authority and adherence to norms can inspire dangerous levels of conformity among the collective. Scenes like the above, which punctured the fourth wall between audience and performer, were key to breaking this conformity.

In An Evening’s Entertainment, stage directions also instruct that the play commence at least half an hour late, and the actors seated among the audience should begin to shift in their seats impatiently and start asking questions. What made theater politicizing was its ability to jar the audience into breaking “the wall of silence” that kept them quietly glued to their seats (122).

What made theater politicizing was its ability to jar the audience into breaking “the wall of silence” that kept them quietly glued to their seats...

This approach to theater recalls the countless viral videos of the past 15 months, featuring activists interrupting politicians and board members in large auditoriums and gala dinners over their stance on Israel's war on Gaza and US complicity through weapons transfers, aerial and naval support. These videos tend to follow a script not unlike the scene above: An activist, or group of them, get out of their seats and sharply break the fourth wall to voice their disagreement with the narrative being presented. (Recently, protestors interrupted an address by then-Secretary of State Anthony Blinken, delivered at the Atlantic Council as part of his goodbye tour, with shouts of “Secretary of Genocide.") Without fail, the surrounding audience members show discomfort at the disruptor rather than the prevaricating political figure. On one level, it is this discomfort that makes the disruptions such effective political actions. On another, the refusal of the audience to sit idly by and fulfill their role as mere spectators to political theater demonstrates an activist potential Wannous understood. He dreamed that his plays would incite such unscripted rebellions among the audience. Of An Evening’s Entertainment, Myers and Saab write, "he hoped that the play, which ends with a literal call to arms, would spill into the streets and spark an insurrection" (xvii).

In a similar vein, Mamlouk Jabir was to be staged at a café, or some other space of communal gathering, in order to, as the playwright wrote in the preface, “break the rigid circular and ritualistic boundaries of theatrical performance” (122). Actors should sit among the audience, so everyone is implicated in the drama. Whereas An Evening’s Entertainment was instructed to start late, allowing the audience to grow agitated, Mamlouk Jabir should begin at an unspecified time: after the initial awkward rigidity of sitting in a formal space with strangers subsides. All of these efforts were intended to “encourage the spectator to speak, improvise, and engage in dialogue” (124).

Throughout the play, Jabir’s entertaining schemes and machinations are punctuated with interjections from the actors playing café-goers, ideally seated among the audience, as well as the townspeople of Baghdad. They periodically speak among themselves, lamenting the dire political and economic circumstances they find themselves in but keeping their heads down to survive. When one man attempts to question the war, he is swiftly shut down: “Better to turn a blind eye and remain with our families than turn blind in the darkness of a prison cell” (148).

I read Mamlouk Jabir with a group of students and workers on our own evening of entertainment in late May of 2024—at the Exeter Liberation Encampment for Palestine, erected by University of Exeter students earlier that month. As was the case at encampments across universities in the United States and Britain, Exeter students were demanding that the university disclose and divest, ending its research partnerships with companies that supply weapons to Israel as well as its partnerships with Israeli institutions in line with the academic boycott. In making these demands, students organized a series of escalating disruptions from shouting down university leadership meetings to “die-ins” at administrative buildings.

What made meaningful theater, for Wannous, was its translatability to a particular moment in time and the political concerns of that moment. Mamlouk Jabir—first performed in 1971—was banned in Syria under Hafez al-Asad, who became president that year. Reflecting on a staging at the Weimar National Theater in Germany in 1973, the playwright described the performance as “skillful but fossilized” because it did not connect to the political environment there (397). A 1990 run in Moscow, conversely, played with the form while adhering to the text. It confirmed for the playwright that in order for a performance to “create the circumstances for dialogue” it must “speak to the elements of its time and place” (397).

The place of the encampment and the time of genocide and unprecedented mobilizing at western institutions to end complicity in Israel’s war allowed for a new dialogue to emerge from the material. By the end of our reading, the sun had set over the Devon hills, and we took out our flashlights and cell phones to read the final pages:

MAN #4. If you’re devoured by hunger and find yourself living on the street . . .

ZUMURRUD. If heads begin to roll and you find yourself being welcomed at the dawn of a miserable day by death . . .

HAKAWATI, ZUMURRUD, AND MAN #4. (Together) If a night thick with horror rains down upon you, don’t forget that you yourself said, “It’s not my concern. Whoever marries my mother, I call uncle.” From the dark night of Baghdad we speak to you. From the night of death and sorrow, strewn with cadavers (206).

The play ends with a forceful argument that the cause of tragedy is not the oppressive regime but the absence of resistance to it: the individual apathy born from the fear the state engenders in its citizenry.

For those of us reading together at the encampment, Wannous’s tale served as a reminder that the opposite is also true: Failure to stem the forces that have enabled the genocide, out of fear or apathy or a sense of defeat, will lead to widening oppression.

A common refrain across the student encampments for Palestine was that “Palestine will liberate us all.”[1] For those of us reading together at the encampment, Wannous’s tale served as a reminder that the opposite is also true: Failure to stem the forces that have enabled the genocide, out of fear or apathy or a sense of defeat, will lead to widening oppression.

This reminder is visible in Israel’s continued violations of international law across historic Palestine, Lebanon and Syria as it expands it occupation in late 2024 and into 2025. It is visible in the US government’s targeting of free speech around Palestine: for example, the anti-BDS legislation adopted by several states or resolution 9495, passed by the House of Representatives in November, allowing the White House to unilaterally remove the tax-exempt status of NGOs alleged to support “terrorism.” Under the second Trump administration, these and other measures will likely be used to target not only Palestine but other, related, causes: from fossil fuel divestment to abolitionist movements. It is visible in the normalization agreements through the Abraham Accords, which have enabled authoritarian states in the Middle East to invest fossil capital into dangerous surveillance technologies that further depoliticize their own citizenry. Incidentally, for Wannous, the true moment of despair was not the military defeat of the Naksa but the beginnings of normalization with Anwar Sadat’s 1977 visit to the Israeli Knesset and subsequent signing of the Camp David Accords. The moment led to a nervous breakdown and a suicide attempt, after which he stopped writing theater for more than ten years (xxi).

While Wannous did go on to write a number of experimental plays in the 1990s, his post-Naksa period resonates most today. In 1996, one year before his death to cancer, in a speech for World Theater Day, he hearkened to the days when theater could cause such “explosions of dialogue” and lamented its eroding space in cultural production.[2] Gaza, it seems, has temporarily jarred people into breaking the fourth wall, causing an explosion he would approve of, despite the ongoing and overlapping crises. The conclusion he offered then, and words often associated with his name today, bear repeating: “Our lot is to hope, and what happens today cannot be the end of time.”[3]

Read the previous article in MER issue 313 “Resistance—The Axis and Beyond.”

[1] Amir Marshi, "Liberation Pedagogy at the People's University for Gaza," MQR, September 2024.

[2] Saadallah Wannous "Theater and the Thirst for Dialogue," Middle East Report 203 (Summer 1997).

[3] Ibid. A translation of this speech is also included in Myers and Saab, Sentence to Hope.