Cell Phones Behind Bars in Lebanon

Exploring a new era of prison communication.

In 2014, the Lebanese TV station LBCI aired a video recorded by prisoners using a smuggled cellphone. “We are here inside Roumieh prison,” a voice from behind the camera declared. The video documented a group of prisoners with their lips stitched to symbolize the start of a hunger strike in protest of the prison’s dire conditions.[1]

In 2019, the network Al Jadeed shared a similar segment, featuring images of prisoners with their lips sewn shut. The prisoners held pieces of paper that read, “Until death or general amnesty” with the date “15/2/2019,” when their hunger strike had begun. The segment also featured a phone call with one of the hunger strikers who explained the mobilization and their demands: “We do not have the most basic necessities of life. They’re not taking us to hospitals… We are living in a very difficult situation here.”[2]

In 2020, at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, Al Jazeera reported on riots in at least two overcrowded Lebanese prisons. Prisoners feared the fast spread of the virus and were demanding to be released, even if temporarily. The article referenced videos shot inside of Roumieh Central Prison and Zahle jail that had been circulating on social media. The videos showed prisoners trying to break down the doors of their crowded cells. Some were injured when security forces tried to quell the riot with live fire.

Another COVID-related report by MTV news featured a montage of footage shot by prisoners in Roumieh prison. In the reel, the camera pans to walls that are crumbling, tiny showers covered in mold and bags of garbage heaped in a corridor. Filthy and threadbare bedding is piled up during the day to make space in the densely packed cells. In the clip, an MTV reporter converses by phone with a prisoner who explains that government claims about specialized care for people with COVID are a lie. Rather, they are moved to a separate building with no healthcare, and when sick prisoners ask for medicine, they are beaten by guards. Halfway through their call, the reporter tells the prisoner on the other end that the audience is seeing images that reinforce what he is saying and thanks those who sent them to MTV. The prisoner responds, “We would like to invite the media…to come in and film the reality inside the prisons.”[3]

In 2022, TRT World published an article on the harrowing and anarchic conditions in Roumieh that incorporated photographs shot and circulated by prisoners. One blurry image of a cell with grime-covered walls and piles of trash was captioned with a quote from the prisoner who sent it: This is “the corridor of the rich.”[4] The floor below “is where the real filth is.” These unhygienic conditions, as the article notes, are a breeding ground for parasitic mites that burrow into people’s skin. Scabies outbreaks are frequent because bodies are crowded together.

While cell phones are considered contraband in Lebanese prisons, in recent years, many such videos and images have surfaced—as the smuggling of this technology has enabled prisoners to communicate with the world beyond bars.

While cell phones are considered contraband in Lebanese prisons, in recent years, many such videos and images have surfaced—as the smuggling of this technology has enabled prisoners to communicate with the world beyond bars. Prisoners use cell phone cameras to document their daily realities and to expose their conditions of confinement. They also use phones to record testimonies and political statements, coordinate mobilizations and communicate with activists and media personnel.

Smuggled cellphones and clandestine communication strategies are part of a long history of prison resistance in Lebanon and the region. Like texts and audio recordings that are covertly smuggled out of prisons, they allow prisoners vital communication with the world beyond bars. In terms of impact, however, this technology has the capacity to reach even wider audiences through television and social media and offer more powerful testimony given the immediacy of its circulation and its audio-visual dimension.

Moreover, cellphone videos offer forms of political mobilization and practices of media production that are distinctly more collective and audience-oriented than less technological forms of prison communications. Within Lebanon's prisons, cell phones influence how prisoners organize, how they strategize about the objectives of actions like hunger strikes and how they capture and share these with broader audiences.

The deplorable conditions in Lebanon’s detention centers are emblematic of the state’s chronic failures and a testament to systematic neglect. In 2022, the prison population was at 191 percent of capacity—almost double what the facilities were built to hold.

The exact number of prisoners is hard to determine: Calculations vary between figures shared by the Ministry of Justice and those shared by non-governmental humanitarian organizations and research and policy centers. According to a 2023 report by World Prison Brief, the inmate population was 9,254 in a system with a capacity for 4,760.[5]

Roumieh Central is Lebanon’s largest detention center. Built during the French Mandate, it is the only facility among the country’s 25 detention centers that was originally designed for incarceration purposes. The others are refurbished governmental buildings, some of which are still considered inadequate for housing detainees. Roumieh has a 1,200-person capacity, yet it currently holds around 4,000 people. Due to this extreme overcrowding, civilians convicted by civil courts are held for months in police stations, gendarmeries and even military prisons, according to the Lebanese Centre for Human Rights. Some facilities, charge prisoners for cell space, and those who can’t pay might sleep on corridor floors.

The country’s unrelenting economic crisis has intensified the scarcity of healthcare, food shortages, lack of sanitation and infrastructural collapse in prisons—a situation that is reflected in a rising mortality rate for prisoners: In 2022, 34 people died in custody due to lack of medical attention. But the problems within Lebanon’s carceral system are structural and historic. Penal laws retain remnants of French colonial rule and Ottoman-era conventions. Detention centers continue to be governed through a quasi-military administration under the Internal Security Forces, making them susceptible to partisan influences, resistant to organizational reform, lacking transparent systems of checks and balances and prone to abuse and torture. For decades, officials have made promises to shift control to the Ministry of Justice, but this change has failed to materialize. Prison authorities still rely on the Ottoman-era Shaweesh system for communication and for the implementation of new procedures and regulations. A Shaweesh is a well-connected detainee appointed to oversee a group of prisoners or administer a prison block; they hold significant power within the inner structure of the prison.

Lebanon’s carceral spaces also reflect entrenched sectarian hierarchies and pervasive social, economic and gender discrimination. The groups most susceptible to arbitrary arrest and detention, that is without legal basis or convicted in a sham trial, are members of migrant communities, LGBT+ individuals and people from impoverished areas. These groups are also the most at risk of abuse in prison.

These multilayered power structures mirror the class inequalities in Lebanese society at large.

Prisoners rely on personal connections to survive in the face of systematic neglect and deprivation. They seek help from their families or support groups to get basic amenities like clothes, hygiene products, food and even mattresses. Prisoners with strong connections (wasta) have a better chance of navigating the system, while detainees from lower socio-economic backgrounds must rely on better-resourced and connected prisoners. These multilayered power structures mirror the class inequalities in Lebanese society at large. They also reinforce and perpetuate a system where clientelism dictates treatment and opportunities within the carceral space.

Moreover, detainees are often segregated along sectarian lines rather than on the basis of their crimes. Roumieh prison’s infamous Bloc B is a case in point. Following armed conflicts between the Lebanese army and armed groups on the northern border with Syria in 2005, authorities initiated a series of sweeping arbitrary arrests, allegedly targeting Islamists. The arrests were not based on a clear legal framework and primarily affected individuals from lower socio-economic backgrounds in northern Lebanon. Because of their sectarian identity, many of these individuals were placed in Bloc B. The media portrays Bloc B as a facility housing Sunni fundamentalist groups, and prisoners there are vilified as Islamist “terrorists.”[6] But in reality, because of sectarian segregation, Bloc B hosts individuals with no proven ties to terrorism, who end up there by virtue of their religious identity.

Beyond the dire conditions of systematic neglect and abuse, suffering is integral to the experience of incarceration itself. Prisoners grapple with uncertainty—their lives suspended in a state of perpetual waiting. The inefficiency of the Lebanese judicial system exacerbates this harrowing existence, as protracted pretrial detention has become the norm. Around 80 percent of Lebanon’s current prison population—approximately 6,600 individuals—are held in pretrial detention.[7] Many have spent years awaiting trial.

In January of 2013, a prisoner, Ghassan al-Qandaqli, was found dead in his cell in Roumieh prison. Citing marks around his neck, the police classified the death as a suicide. But shortly after, a low-quality cellphone image and a video transmitted from the prison found their way to the news. The photo documented bruises and cuts on al-Qandaqli’s back, and the video showed him pleading for help. The content aroused suspicion that he had been murdered, triggering forensic and journalistic investigations into the cause of death. Reports indicated that the prisoner had been choked to death by three other inmates in Bloc B, who later hanged him in the restroom to disguise the murder as a suicide. Further investigations suggested that the killing was related to a prison escape attempt and was ordered and executed by inmates from the “third floor,” the level of Bloc B allegedly occupied by prisoners with high-level connections and power.

Lebanese news media relied heavily on photographs, videos and voice recordings from inmates when reporting on developments in the case. Some prisoners relayed the horror imposed by the third-floor inmates while others attempted to sway and influence investigations and public opinion through recorded videos with differing accounts of the cause of death. Many of these recordings have been deleted from social media platforms. But one that is still available, shared in a report by LBCI news, features footage of prisoners attempting to disprove the alleged murder by reenacting the suicide.

Lebanese prisons have frequently been the subject of media attention, given their notoriety. But 2013 marked an inflection point when it comes to prisoners' engagement with digital technologies in Lebanon. Since then, local news outlets as well as international media have frequently incorporated images, videos and voice recordings taken and circulated by prisoners. They also occasionally broadcast calls with prisoners.

News channels in Lebanon often reuse and repackage prisoners’ recordings to fit the outlet’s political partisan positions. Recordings are stripped of their political meanings and inscribed within a partisan narrative that aims to vilify prisoners. One example of such politically calculated sensationalism was an MTV segment from September 2020, on the spread of COVID in Bloc B. After citing figures of the number of prisoners and guards who had been infected, the reporter stated that officials from the Interior Ministry claimed Bloc B “terrorists” might be infecting themselves deliberately to draw attention to the plight of prisoners. The claim was articulated alongside a recording from the prison showing prisoners congregating in protest of their conditions, therefore creating a visual link between prisoners’ congregation in protest and the inscription of prisoners as COVID self-inflicting “terrorists.” The segment failed to mention the political demands behind such a protest, instead using it as B-roll for the station’s sensationalism.

2013 marked an inflection point when it comes to prisoners' engagement with digital technologies in Lebanon. Since then, local news outlets as well as international media have frequently incorporated images, videos and voice recordings taken and circulated by prisoners.

Social media platforms like YouTube and Facebook are also key venues for the circulation of cellphone recordings. Some Facebook pages use prison recordings to promote particular political or sectarian ideologies, but in general, these platforms allow prisoners greater—often uncensored—control of their material and can foster a more intimate connection with viewers.

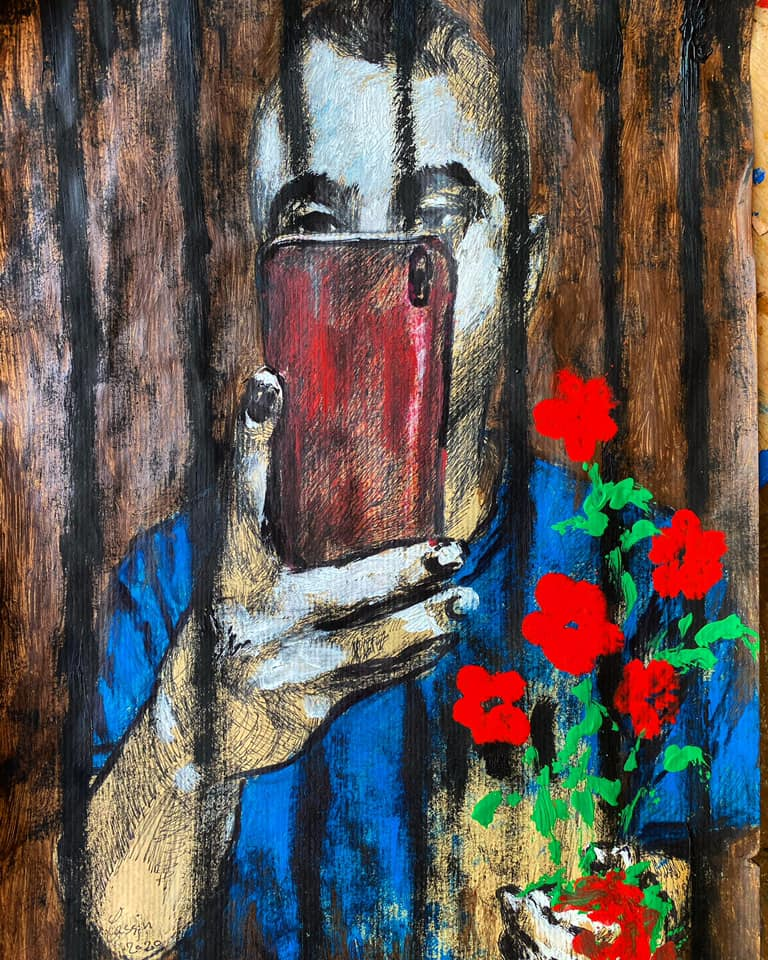

Prisoners do not only use social media platforms to circulate images of riots and conflicts but also mundane activities: groups of people eating or conversing or details of the squalid environments of their lives behind bars. While some of this content may appear uneventful, it captures the lived experience of incarceration from the viewpoint of the prisoners themselves, down to the prison bars partially obstructing their view.

Prisons in the Arab world have historically been breeding grounds for revolutionary ideas, literary formations, creative expression and innovative media practices.

There is a vital tradition of Arab prison literature. Novels such as Al-Sijn (The Prison) by Nabil Suleyman (1972) and Thuna'iyyat al- Sijn wa al-Ghurba (The Duet of Prison and Alienation) by Egyptian writer Fathi Abdul Fattah (1995) do not only relay experiences of incarceration under authoritarian regimes but also contribute to political thought and conceptual work on political philosophy and alienation. Other creative expressions emerging from the prison include poems and songs, most notably the extensive body of work of Sheikh Imam and Ahmed Fouad Nagm, who both spent time in Egyptian prisons.

The contemporary extension of these practices through the use of illicit cellphones and internet access has given rise to a new era of prison communication. These recordings are part of a longer history of finding creative strategies to resist carceral systems.

Communication strategies have evolved and morphed in relation to the needs of prisoners, their political demands and the broader political context in Lebanon.

Communication strategies have evolved and morphed in relation to the needs of prisoners, their political demands and the broader political context in Lebanon. Moreover, evolving techniques of filming, documenting and engaging with audiences allow inmates to continuously modify their communication strategies. For instance, instead of just filming riots or recording their dire conditions in testimonials, some mobilizations are purposely planned and staged for the camera. Prisoners might record themselves congregated silently in a semi-circle while a spokesperson in the middle eloquently voices their demands. Rather than pleading into an abyss, the spokesperson directly addresses the audience, often naming politicians who are to blame for their plight.

Cell phones have a distinctive material value in prison, and the ability to access this technology depends on prisoners’ socio-economic backgrounds. Like other forms of contraband, cell phones are smuggled into prison to be bought and sold. Mobile credits, too, are treated as currency. Given the public impact and reach of prison cellphone recordings, Lebanese authorities have strived to limit prisoners’ access to mobile technologies. In 2013, the government invested $650,00 in an internet-jamming system. But it was never effectively activated because, aside from corruption and incompetence, halting mobile communications in prison would intercept the internet connection from the suburban residential area of Roumieh surrounding the prison. As such, prisoners have maintained access to cellphones and internet connections, and their recordings continue to be featured on social media and on the news.

Some prisoners use this technology to promote and project sectarian agendas, emphasizing their identity alongside their demands. For instance, prisoners might declare that they are Maronite or Christian before appealing to sectarian leaders. Others address their recordings to Nabih Berri as their Shi’a representative. In this way, prison recordings can both reflect and reinforce sectarian dependencies and the functionality of clientelism in the context of a failed state.

Prisoners use their recordings to expose the systemic neglect and abuse perpetuated by the state and the entrenched sectarian and class-based inequalities within the prison system.

Local and international media outlets often frame prisoners’ use of contraband cell phones and communication practices as either an illicit byproduct of corruption, or else an indulgent luxury with disruptive effects and deserving of harsher punitive measures. But examining the material produced by prisoners shows that cellphones offer a means to project valuable insights into the hidden realities of the Lebanese penal system. Prisoners use their recordings to expose the systemic neglect and abuse perpetuated by the state and the entrenched sectarian and class-based inequalities within the prison system. Instead of viewing contraband cellphones through the lens of criminality or terrorism, these illicit communication strategies represent the resilience, ingenuity and politics of those who, even in the most oppressive circumstances, continue to find ways to resist, communicate and assert their humanity.

[Chafic Tony Najem is a post-doctoral fellow at the Institute of Advanced Study in the Global South at Northwestern University in Qatar. His research explores illicit communication and media practices in carceral spaces.]

This issue of Middle East Report, Carceral Realities and Freedom Dreams, has been produced in partnership with the Orfalea Center for Global and International Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and Security in Context.

Read theprevious article.

Read thenext article.

This article appears in MER issue 312 “Carceral Realities & Freedom Dreams.”

[1] LBCI Lebanon, “LBCI News-Exclusive: Prisoners in Roumieh sew their mouths shut, announcing the start of a hunger strike,” YouTube, February 26, 2014. [Arabic]

[2] Al Jadeed News, “In Roumieh Prison: Mouths stitched and prisoners transferred to hospital - Rachel Karam,” YouTube, February 18, 2019. [Arabic]

[3] MTV Lebanon News, “A prisoner in Roumieh tells MTV about the miserable reality inside the prison,” YouTube, September 26, 2020. [Arabic]

[4] Priyanka Navani, “Lebanon's prisons: A microcosm of disease, sectarianism and near-anarchy,” TRT World, January 4, 2022.

[5] "World Prison Brief Data: Lebanon,” World Prison Brief, October 2023.

[6] Esperance Ghanem, "Lebanon's main prison a hotbed for terrorists," Al-Monitor, August 29, 2014.

[7] "Lebanon: Harrowing Prison Conditions," Human Rights Watch, August 23, 2023.