Cairo's Incarcerated Geographies

In 2015, the Egyptian government announced a series of urban development plans, a schema that included having a city free of slums.

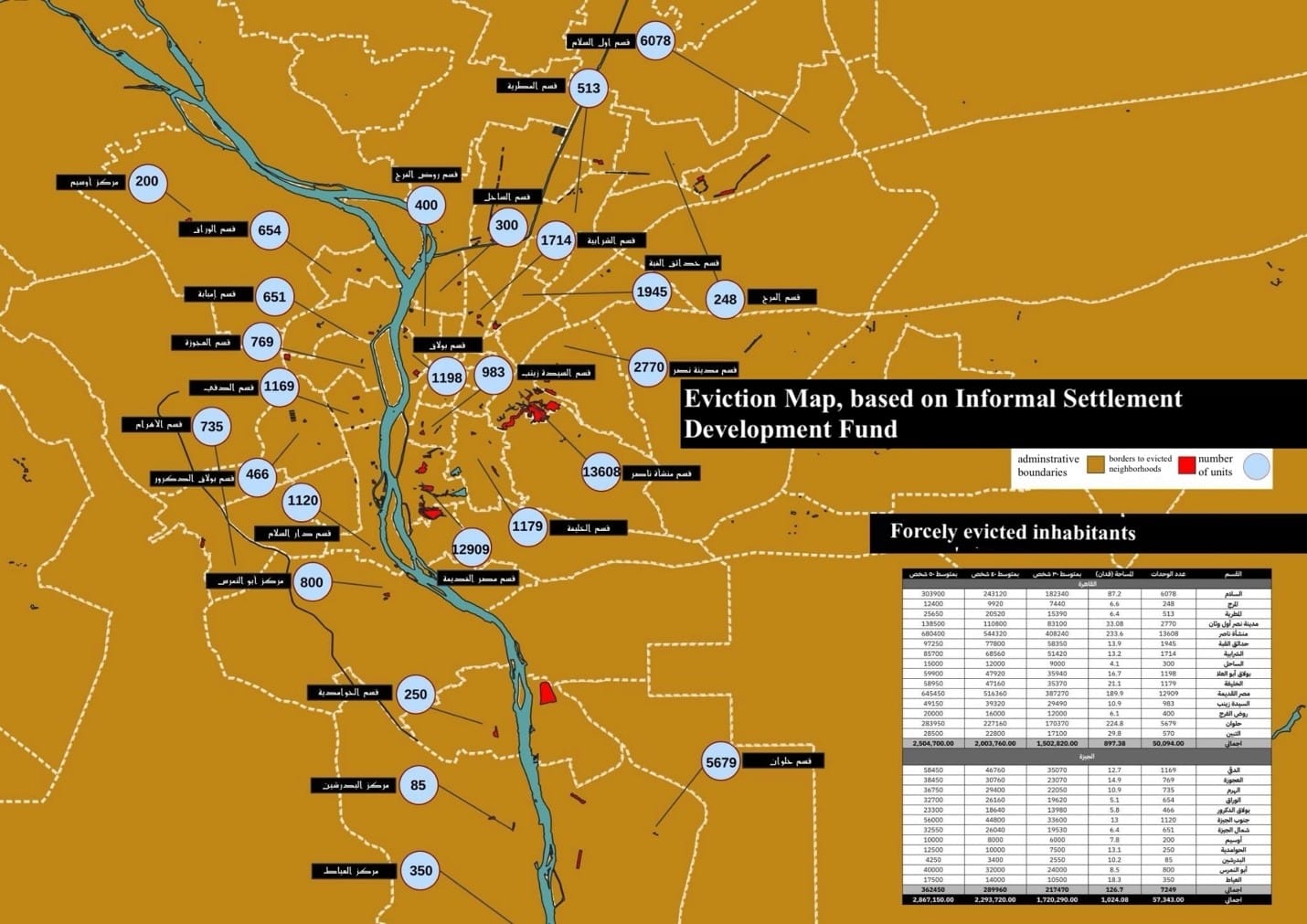

As part of this plan, the state implemented a policy to relocate residents of so-called unsafe areas to new neighborhoods and redevelop existing neighborhoods using a combination of government investments and private capital. The designation of these neighborhoods as unsafe had been applied in 2008 by the Informal Settlements Development Fund (ISDF).

The policy was one of a number intended to legalize urban destruction in the name, not just of development, but also security. Other policies included the establishment of a committee in 2016 to reclaim state owned lands, like al-Warraq Island, and the destruction of units that had been built without a license. More recently, a Building Reconciliation Law mandated that millions of residents must pay fines in order to legalize their housing units and keep their property.

Also Read: "The Urbanization of Power and the Struggle for the City" MER issue 287, Summer 2018.

Maspero Triangle, a neighborhood of 5,000 inhabitants, was the first neighborhood to be impacted by the wave of changes. It was exceptional, however, in that residents were compensated. The compensations were both in kind, for example, a resident would receive social housing or have the option to return to the same neighborhood after the urban redevelopment, where they would have to pay mortgage for 20 years to own the apartment. They could otherwise opt to receive money as compensation, which many families did.

In other neighborhoods, thousands of families got nothing in return for their eviction. In Al-Madabegh in Old Cairo, only one third of the families received apartments in the social housing project. The other two thirds were evicted without relocation or compensation. An estimated 2.8 million inhabitants were evicted from 2018 to 2022. Meanwhile, social housing provided by the state amounted to only 30,000 apartments, enough to house about 150,000 residents. Anyone who objected to the relocation or destruction of their home was imprisoned for up to a few weeks.

These evictions are part of a broader effort to securitize Cairo’s urban geography. Under the presidency of Abd al-Fattah al-Sisi, incarceration has become a mode of governance. Hundreds of thousands have been imprisoned without cause and without fair trials. But space has also become carceralized in the years following the 2011 revolution and 2013 coup.

The 2011 uprising had ushered in a new sense of belonging to the city. Committees were formed in neighborhoods to tackle local challenges, like the scarcity of sanitary services and building deterioration. One month after the coup that overthrew Mohamed Morsi’s government, on August 14, 2013, a four-hour massacre against the Muslim brotherhood resulted in 800 deaths. The Rabaa Massacre was the beginning of what could be called the incarceration of space, when the surveillance of places became a normal feature of urban life. Tahrir Square was closed, and military tanks and personnel stood on constant guard. Most of the smaller squares in Cairo’s downtown, including Talaat Harb Square and Mostafa Kamel Square were also heavily policed.

The surveillance extended from Tahrir and downtown, to other neighborhoods across Cairo. A curfew was announced from August 2013 until December. In addition to the everyday presence of military tanks in the streets, security forces established hundreds of checkpoints. Expired national ID cards were rejected and groups of more than five people were not allowed to pass through.

The majority of residents who were affected by the wave of evictions that began in 2018...were the same people who had participated in the 2011 revolution and in the subsequent uprisings in 2013.

The massive wave of urban construction and destruction, beginning in 2015, has helped extend the effects of this counterrevolutionary state power. The majority of residents who were affected by the wave of evictions that began in 2018, for example, were the same people who had participated in the 2011 revolution and in the subsequent uprisings in 2013.

In 2020, the Ministry of Defense established a new unit in each governorate: the Spatial Changes Monitor. Nestled within the Military Survey Department, this unit effectively polices construction on a local scale. Every person who does not obtain permission for spatial changes—like adding a room or floor to a building or demolishing part of a house—is now subject to legal punishment and a military trial. The prime minister, Mostafa Madbouly invoked national security when explaining the policy: “We will completely stop attempts to construct illegally, whether on agricultural lands or otherwise, considering that this has become a national security issue, as building violations and their effects threaten national security.”[1] Without naming these threats to national security, the state nevertheless assumed complete control over development in their name, effectively excluding Egyptian society from taking part in place-making processes.

Moreover, the wave of megaprojects currently under construction, including Sisi’s new administrative capital in the eastern desert areas between Cairo and the Suez, are leading to new forms of spatial securitization in the city. The new city is set to include eight residential zones, two governmental zones, entertainment and recreational zones, investment zones, a diplomatic district, a central business district, a presidential palace district and more. According to 2021 figures released by Egypt’s official statistical agency, 40,000 bridges were built in one year across the country in order to accommodate more traffic and elevate roads and highways. In addition, almost 100,000 miles of roads were constructed. On top of destroying green spaces in Cairo’s old middle to upper class neighborhoods, the new road network has expanded the control of the state security apparatus over the city, increasing the capacity for surveillance. Now, on the anniversaries of the 2011 revolution, security personnel can be found standing in a row on flyover bridges, observing the movement of people. Security cameras are mounted in newly constructed elevated places. Additionally, 6,000 CCTV cameras are located in the new capital.

This massive networks of roads and flyover bridges has also segregated communities, isolating many neighborhoods, and making it harder to get around on foot. Walking has become difficult in several neighborhoods: The new roads lack walk signals, making Cairo’s busy streets more dangerous, and pedestrian related traffic deaths appear to be on the rise.

Not only has people’s movement become circumscribed, their control over space is limited. Residents of Cairo describe the changes to their everyday routes as leading to a feeling of being out of place. Yet they face imprisonment for objecting to the geographical changes. At the time of writing, residents of al-Warraq Island, who are facing evictions due to the state’s 2016 land reclamation, are continuing to demonstrate against demolitions. Many have faced cycles of arrests and release in the process. Construction and destruction have rendered Cairo’s urban geography—and urban life itself—incarcerated.

[Omnia Khalil is a lecturer in international relations and anthropology at City College New York.]

This issue of Middle East Report, Carceral Realities and Freedom Dreams, has been produced in partnership with the Orfalea Center for Global and International Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and Security in Context.

Read theprevious article.

Read thenext article.

This article appears in MER issue 312 “Carceral Realities & Freedom Dreams.”

[1] Hind Mukhtar, “The government announces the establishment of a unit for spatial changes to monitor any illegal construction immediately,” Al-Youm Al-Saba’a, August 30, 2020. [In Arabic]