Energy Politics and Africanfuturism—A Conversation with Nnedi Okorafor

Nnedi Okorafor is an award-winning writer of science fiction and fantasy for adults and youth.

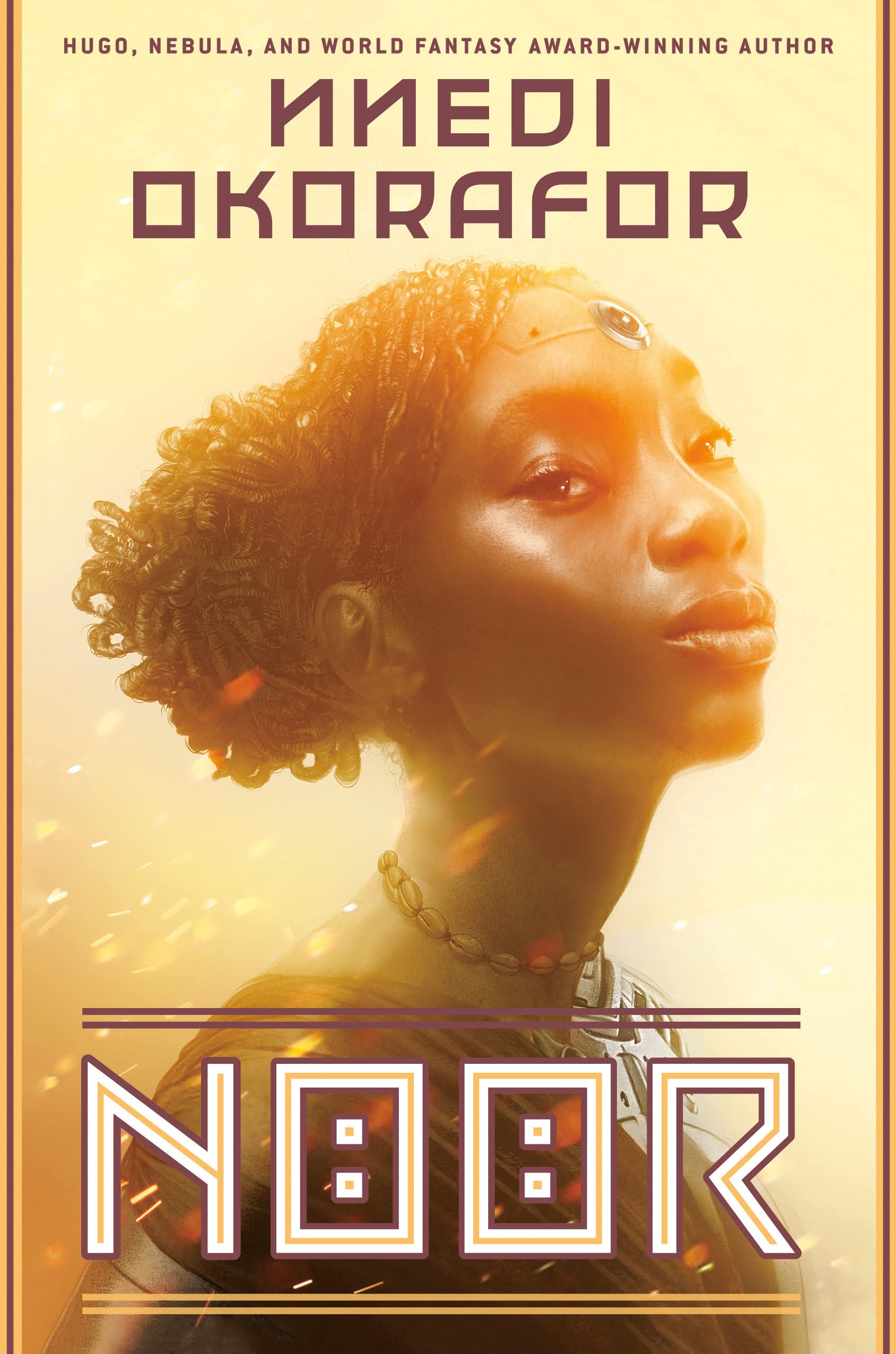

Her latest work is Akata Woman (Penguin, 2023), an Africanfuturist novel that follows her previous work, Noor (Penguin, 2022). Noor features the protagonist AO, whose experience of disability, bio-tech and trauma shapes her trajectory in confronting the dangers—and possibilities—of energy politics and corporate domination in a near-future Nigeria. The Sahara and its potential role in a renewable energy future figure centrally in the novel, which draws on the imaginaries offered by the NOOR solar installation in Ouarzazate, Morocco. Karen Rignall is an anthropologist at University of Kentucky and previous MER contributor. Among other topics in environmental and energy studies, she has researched the socio-ecological and political dynamics of the Moroccan Noor Solar complex, the anchor for the country’s ambitious renewable energy strategy. The two spoke over zoom on March 29, 2024 about the inspiration behind Okorafor’s work and how technology fits into imaginaries of the future. Their conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Karen Rignall: We first connected a few years ago when you reached out about my research on solar in Morocco in preparation for your book, Noor, so let’s start our conversation there. Could you speak about your preparation for the novel?

Nnedi Okorafor: Before the start of the pandemic, a publication approached me and asked me to write a journalistic article on one of the biggest solar complexes in the world, the Noor complex in Ouarzazate in Morocco. The article was going to explore the idea that through clean energy the future of humanity could actually be in wastelands in the desert, which led me to the idea for Noor. I was looking at the Sahara Desert, which many see as a dead place—I love the desert, but one of the dominant ideas about the desert is that it looks dead—I was thinking about the idea of an infinite amount of energy already there in the desert through the sun. I thought, “What if the answer is in these places that we see as dead?” That led me to start looking at solar power.

The project died when the Covid lockdown happened. But through the article, I gained access to the complex. So much of the book was inspired by my trip to Ouarzazate. The whole trip was eye-opening. Research is one thing but seeing it up close and understanding what it all means, what it interrupts as well as how it affects the community is another. It just went right into the book because a lot of the ideas that I was exploring were deeply connected to what I was seeing. I asked the manager who showed me around the Noor complex to tell me one thing that was holding back solar power, and he said: perfecting a way to transfer energy. In my book, the main character, AO, comes up with the solution—wireless transfer. She’s one of the nomads who lives near the Noor complex, from one of the tribes whose land was being taken by the complex. They were being dispossessed, and yet she comes up with a solution for energy storage. It is a very powerful story of a local girl who changes the world.

Karen: If you ever saw the map of Morocco’s solar plan, the proposed installations are in politically restive areas, places that rose up against the king after independence or are the subject of other political contestations. There's sun all over Morocco. Installations could be put anywhere, but they put them in historically marginalized places with a history of social mobilizations.

Also Read: "Life in the Vicinity of Morocco’s Noor Solar Energy Project" MER issue 298, Spring 2021.

This really is about political control and capital accumulation. And all of these dynamics around solar energy are happening too with the cobalt, silver, copper and other mines. This is about directing the state toward certain financial interests and with a clear objective of moving both mining and renewable energy initiatives from Morocco into Africa south of the Sahel. Morocco has positioned itself very much as a bringer of capital expertise to African countries, and so there is an interesting political resurrection of these ties to various African countries. To what extent do you incorporate your thoughts about the geopolitics around energy into your work?

Nnedi: I didn’t sit down and think “Oh, I'm going to write a political book,” but I am a person with ideas about environmental politics. When I was researching for the original article on the Noor plant, I learned about clean energy and all that needs to be done. The main culprits are the big corporations and leaders who have the power but are ruled by money. They don't care about the environment. I think that my writing is probably my way of addressing some of these issues that you raise. That's why I like to deal with the future more than the present. In the future, I can look farther down the line after things have happened, and it feels like there is more I can do from that vantage point.

Karen: You mentioned before how these spaces are constructed as “dead.” It made me think about how people who know the desert know how alive it is and often keep those secrets. There’s always been fugitive people in the desert. Your book touches on questions of ownership and sovereignty. Who owns and can appropriate clean energy? I love that in your work you kind of tack between these big questions of political sovereignty but also the questions of bodily sovereignty as in the characters’ very visceral descriptions of pain because of her disability and experiences of trauma, which lead to her extensive cybernetic modifications. Can you speak to how those issues connect?

When I look at climate change, when I look at the way that we treat the planet, it is very personal. It is connected to the way we treat our bodies

Nnedi: All of it is connected. What makes something valuable when looking at a place that you consider dead or a wasteland? If you think it is useless, or that it has no value by the definition of capitalism, then you assume that nobody owns it, or that you can use it for your own purposes. But that ignores what existed there before you came along and redefined it. These concepts of ownership also come up when we consider the Earth as a body, the planet as a body. And I think we can ask the same questions about the main character—questions of ownership and of choice. When it comes to AO’s experience of chronic pain and the consequences of her choices about her body (she chose to have these extensive cybernetic transformations to her body) that was all a part of the story that I wanted to tell, which also relates to disability. A lot of it came from my own personal experiences, as I have my own disability. When I look at climate change, when I look at the way that we treat the planet, it is very personal. It is connected to the way we treat our bodies.

Karen: The desert has not only been constructed as a wasteland but also as a forbidden barrier. In reality, for many millennia, it has been a point of connection. Sahel means “shore” in Arabic. It is not a barrier; it’s an ocean of connection. I'm wondering how you envision that space because you bring in North Africa, you bring in the Fulani presence. Do you envision this space as liminal? Tell us a little bit about how you imagine this space.

Nnedi: I have been to so many different deserts, I'm obsessed with them. I mean, I live in Phoenix for a reason. I think there's a mystical aspect to the desert. It is spiritual, and I feel it strongly. When I visited the Noor complex, I was with my daughter. During that trip, we went into the Sahara, right on the border between Morocco and Algeria. I do view it as a liminal space. As you said, Sahel means shore. I see shifting, like water. It is a place where things are shifting constantly. Our guide was leading us, and the quiet was so loud, so complete, but at the same time it's connected to so much. There is so much life and energy there. I see it as a mystical place where a lot is possible.

Karen: I was struck by your complex depiction of the relationship between the areas north and south of the Sahara. How do you interpret their interconnection from a Nigerian perspective?

Nnedi: A lot of my perspective on that actually comes from traveling to various parts of the Middle East. Even before I was a writer, I was a listener. That was how I started to understand the complex relationship between, for lack of better terms, the Middle East and Africa—by listening and watching. I could see, first of all, the melding of cultural influences. One bleeds into the other. I've also spoken to a lot of the African immigrants in those parts of the world and listened to their issues especially around discrimination. I think a lot of my understanding and my point of view on the complexity comes from my travels, but also, I grew up hearing about some of these things. My mom was born in Jos, a city in the northern part of Nigeria where there is a strong Arab influence. I also heard about the Fulani people and the conflict of the Fulani herdsman, which has always fascinated me. The politics, the rage from all sides and the influence of Middle Eastern cultures coming down.

Karen: At the same time, your work does not idealize or romanticize traditions. You're not necessarily saying, “how can we go back to the old Fulani ways?” Nor are you painting this as a place of pristine tradition or purity in contradiction to a corrupt Nigerian government. I was curious about that complex depiction of what it means to be authentically tied to this place.

Nnedi: I'm always interested in traditions. Tradition is alive, and it evolves. It's not a dead thing. It's not an inanimate object that never changes, but there is also a core that makes it what it is. I do not romanticize it, but I think that there is always something to take from tradition. You can leave stuff that doesn't work, but stuff that does work is often old and has worked for a long time. Just because something is old does not make it useless, and just because something is new does not make it innovative. I think that looking at the ancient and the modern, the traditional and the non-traditional, I always ask: What can I take? What is useful? Then I mash them together into their own thing. I think that is the best of humanity: taking the good stuff and being clear enough to leave the bad stuff behind.

Karen: That leads me to the inevitable question about the role of technology in your fiction. Tell us a little bit about central theme of technology and the futurist dimension of your work?

I knew that I wanted to address the issue of Nigeria's oil dependency: What happens when oil is no longer something that the world is pursuing?

Nnedi: This is an Africanfuturist narrative (not the same as Afrofuturist). Africanfuturism is very concerned with what has been, what is and what can be. I wanted to see a near-future Nigeria with all of its glory, problems and potential. What are its issues? What would happen if some of those issues were solved and some weren't? I knew that technology would be there. I knew that I wanted to address the issue of Nigeria's oil dependency: What happens when oil is no longer something that the world is pursuing? What happens to those countries that made their fortunes from having oil or those that were ravaged for having oil? I thought about what would replace oil. This was where my idea of “periwinkle grass” came in: a genetically engineered super tough grass. And again, when I look at technology, I think about that idea that just because something is new that does not make it better and just because something is old, it does not make it outdated. In my book, periwinkle grass cleans the air. People eat it, but it is also invasive.

And then the main technology in the book are the Noors: these giant wind-harnessing devices designed to respond to a natural disaster that causes a perpetual windstorm in northern Nigeria. In the book, we've got this windstorm that was already there, and then these humongous devices are built to harness that wind energy from the disaster. There's a whole thing about the disaster—I don't want to give away too much, but they created a “natural” disaster in part of Nigeria (and I have ideas of who the “they” are, but I'll leave that aside). Technology is used to create a natural disaster, which they then harvest wind from. It’s not a simple dystopia. Technology has solved a lot of the worst problems in Nigeria, but it has also created more problems. So that’s the complexity of it. We know that technology is not an evil thing in itself; it’s the minds behind it and how we use it. That is where the issue can be: We have technology solving problems and creating problems.

Karen: There is an inherent ambivalence that you don’t want to necessarily resolve. Do you see your work as a cautionary tale?

Nnedi: That is a good question. The main character, AO, becomes something great but only because of the corruption in her. She was born a certain way that was manipulated and then decided to lean into the biotechnology opportunities. The technology, or rather the creators of the technology, are also corrupt. Yet they create this technology that helps a lot of people. Do we want it to exist? Do we not? Is it a cautionary tale? Or not?

I think there are aspects that are a cautionary tale, but there are also aspects about AO that do not make it one. Too often, people write characters who are insecure or scared of their incredible abilities, but AO leans into them. She is very confident about who she is and what she is. But we see that this also leads to violence. So, I think it's too simplistic to call it a cautionary tale. There are warnings in it, but there is also encouragement as well.

Karen: When we think about speculative fiction, it is often about imagining not only the future but a potentially better world. Sometimes readers look to speculative fiction to give us ideas about what that might look like. How does writing toward a better future figure into your work?

Nnedi: My second novel The Shadow Speaker is about a post-apocalyptic world. In that world, I was thinking about what would happen if there was a nuclear holocaust, but it was not that bad of a thing. What if it brought amazing things back? Then I wrote Who Fears Death, which is even more apocalyptic. I started thinking I needed to see more positive stories because what we imagine is what we get. It is easier to write a story in which everything is terrible, dark and disturbing. That sells well. People love that, including me. But we need to balance out those dark narratives with hope.

We need to normalize imagining hope. Because if we don't, hope is no longer normal.

We need to normalize imagining hope. Because if we don't, hope is no longer normal. These days we have an abundance of cautionary tales around the things science fiction writers are saying not to create. I think that, for the sake of hope and ideas, we need positive stories that imagine solutions. It is not that all my stories are going to be happy, but there is hope that things can get solved. What would that look like? That is what led to me writing Binti. With Noor, I was thinking, what happens if we solve some of these problems? I think we need to see more of that. I think that is an important job of science fiction and storytelling in general.

Karen: You're not going for a Hollywood ending that proposes an easy technical solution: “If we do this cloud bubble or that other fix our problems are resolved.” Your solutions are complex, and they are, at least to my anthropologist ears, social and essentially about human interconnection. At the end of the day, you place relationships at the center of your potential future.

Nnedi: That is definitely at the core. I think the solutions lie in the social. We can make amazing technology, but the social part of it is what will corrupt us or lead us to a better world.

Read theprevious article.

Read thenext article.

This article appears in MER issue 311 “Post-Fossil Politics.”