'Undesirables' and the Mediterranean Graphic Novel

Aomar Boum on tracing the holocaust to North Africa through his new graphic novel with Nadjib Berber.

Aomar Boum on tracing the holocaust to North Africa through his new graphic novel with Nadjib Berber.

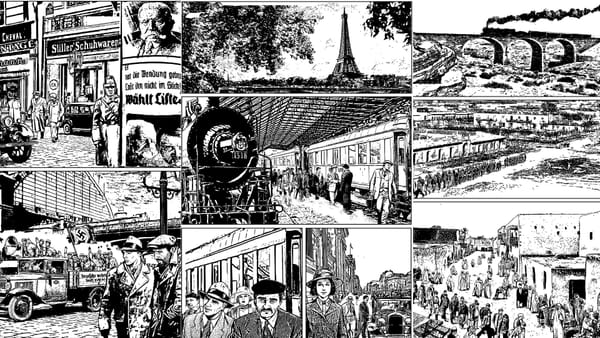

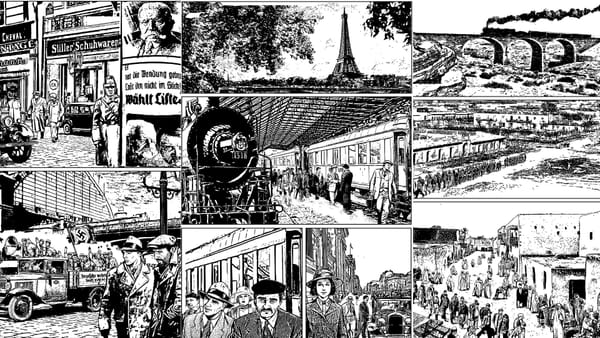

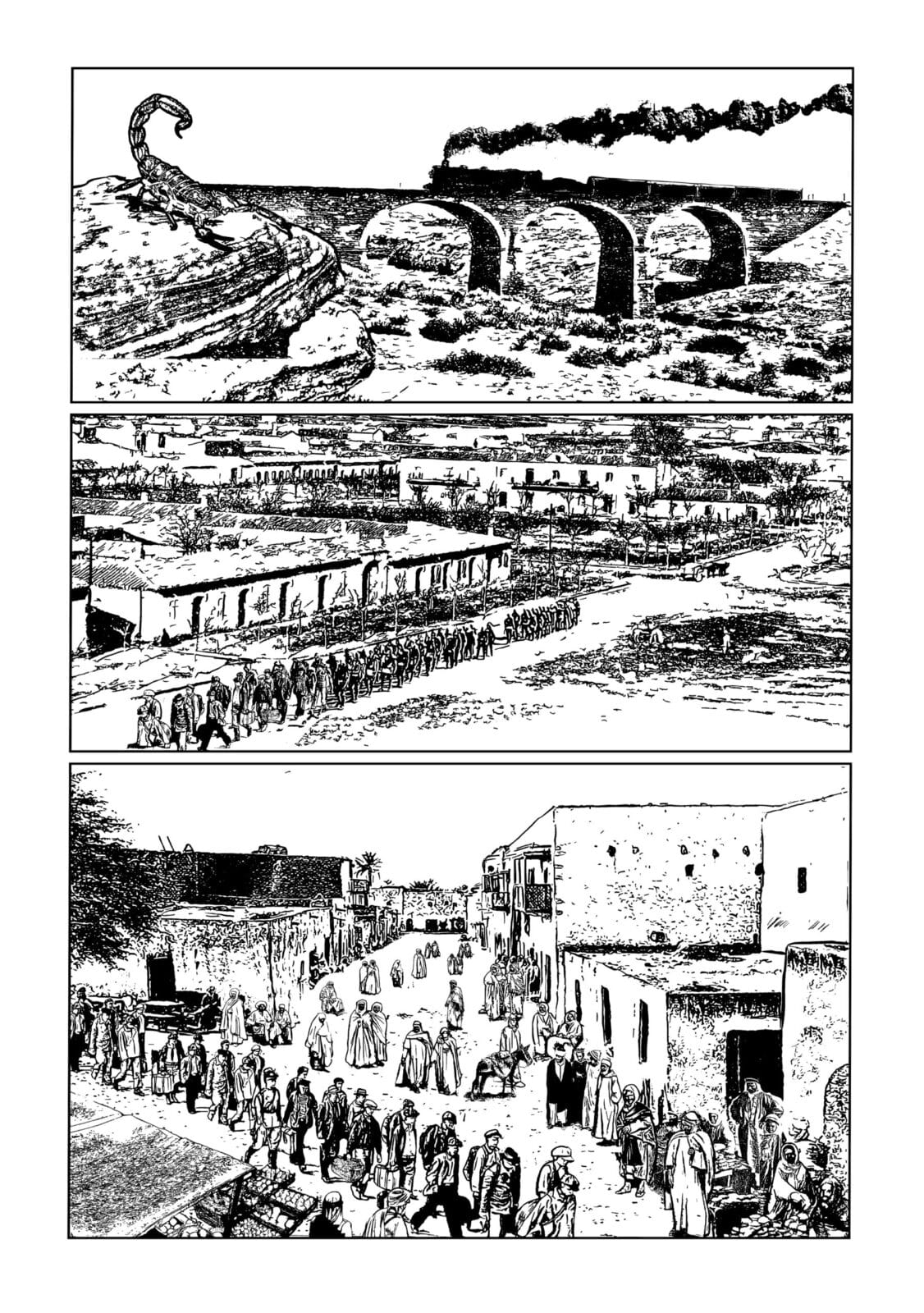

[su_dropcap style="simple" size="4"]T[/su_dropcap]he recently published graphic novel, Undesirables: A Holocaust Journey to North Africa (Stanford University Press, 2023), chronicles the lesser-known events surrounding the internment of political opponents and Jews in seven camps throughout Vichy North Africa during World War II. The protagonist is a Spanish-German Jewish journalist and activist named Hans Frank. The reader accompanies Hans on a journey from Nazi Germany, at the rise of the Third Reich, through Spain during the Civil War, France and Norway during the Nazi invasion, and finally to Algeria and Morocco as they fall under the control of Vichy France. Along the way, deep connections between oppression under colonialism, fascism, and anti-Semitic regimes are illuminated while the work also retraces an international network of militants working against these forces. To bring this historical ethnography to life, Aomar Boum, a historical anthropologist and Maurice Amado Chair in Sephardic Studies at UCLA, collaborated with Nadjib Berber (Nad), a well-known cartoonist from Algeria. In March of 2023, Elizabeth Perego, historian and author of Humor and Power in Algeria, 1920 to 2021 (Indiana University Press, forthcoming), interviewed Boum to discuss how this project came together and its significance as a form of historical narration. Sadly, in the process of preparing for this interview, Nadjib Berber passed away. This conversation about one of his final projects is dedicated to his memory.

Elizabeth Perego: You delve into this story briefly in the afterward but how did the idea to create the first graphic novel about the Holocaust in North Africa initially come about?

Aomar Boum: The idea was born in the archives of Holocaust Museums around the world and developed in conversation with Holocaust and North African studies. In 2006–2007 I joined the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum as the Judith B. and Burton Resnick Fellow, where I researched the circulation of antisemitic discourse in French Algeria after the Crémieux decree and its reproduction in colonial settlers’ newspapers especially between the 1880s–1890s. During my residency, I was introduced for the first time to an embryonic debate about World War II, North Africa and the Holocaust. The conversation was mostly around a recent publication of Robert Satloff’s book Among the Righteous: Lost Stories from the Holocaust's Long Reach into Arab Lands (PublicAffairs, 2006). While this was not the first time that the question of the Holocaust and the status of North African Jews under Vichy was invoked, Satloff's argument for Yad Vashem’s need to commemorate Arabs and Muslims who protected Jews during World War II was a new proposal in the field of North African and Holocaust Studies.

I joined the museum for the second time as a postdoctoral fellow during the academic year 2012–2013 to work on post-Holocaust political debates in Morocco, especially in the aftermath of a growing debate in Morocco around the role of Sultan Sidi Mohammed ben Youssef in saving Moroccan Jews during World War II. During that year, I discovered a set of documents about labor camps in the archives of the International League Against Racism and Anti-Semitism that dealt with topics such as labor camps, the relationship between Jews and Muslims, Nazi and Vichy anti-Semitic propaganda in North Africa, Vichy racial policies in the Maghreb and Muslim responses to ant-Semitism and racism. I was able to unearth a large corpus of documents that pictured the stories of refugees and their internment in labor camps throughout the region. I thought it was important to translate this academic research into a comic story for general readership. At the end of 2015, I talked to Nadjib Berber (Nad), who had just been diagnosed with kidney cancer, about the possibility of collaborating on a graphic novel on European Jewish refugees in North African labor camps during World War II. He welcomed the idea, and we started our collaboration in 2016.

Elizabeth: Could you say a bit about how you collaborated with Berber (known to Algerian and Tunisian readers as Nad) for the graphic novel? What were your goals for the work?

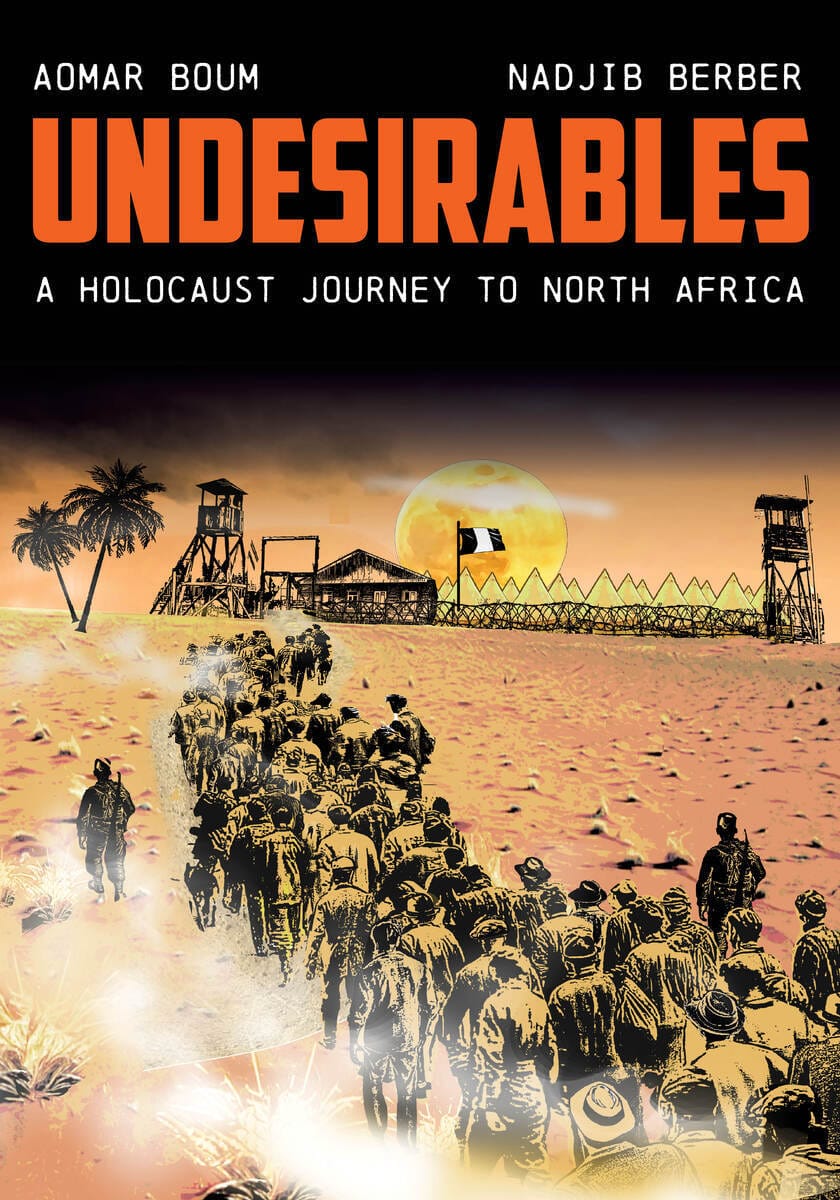

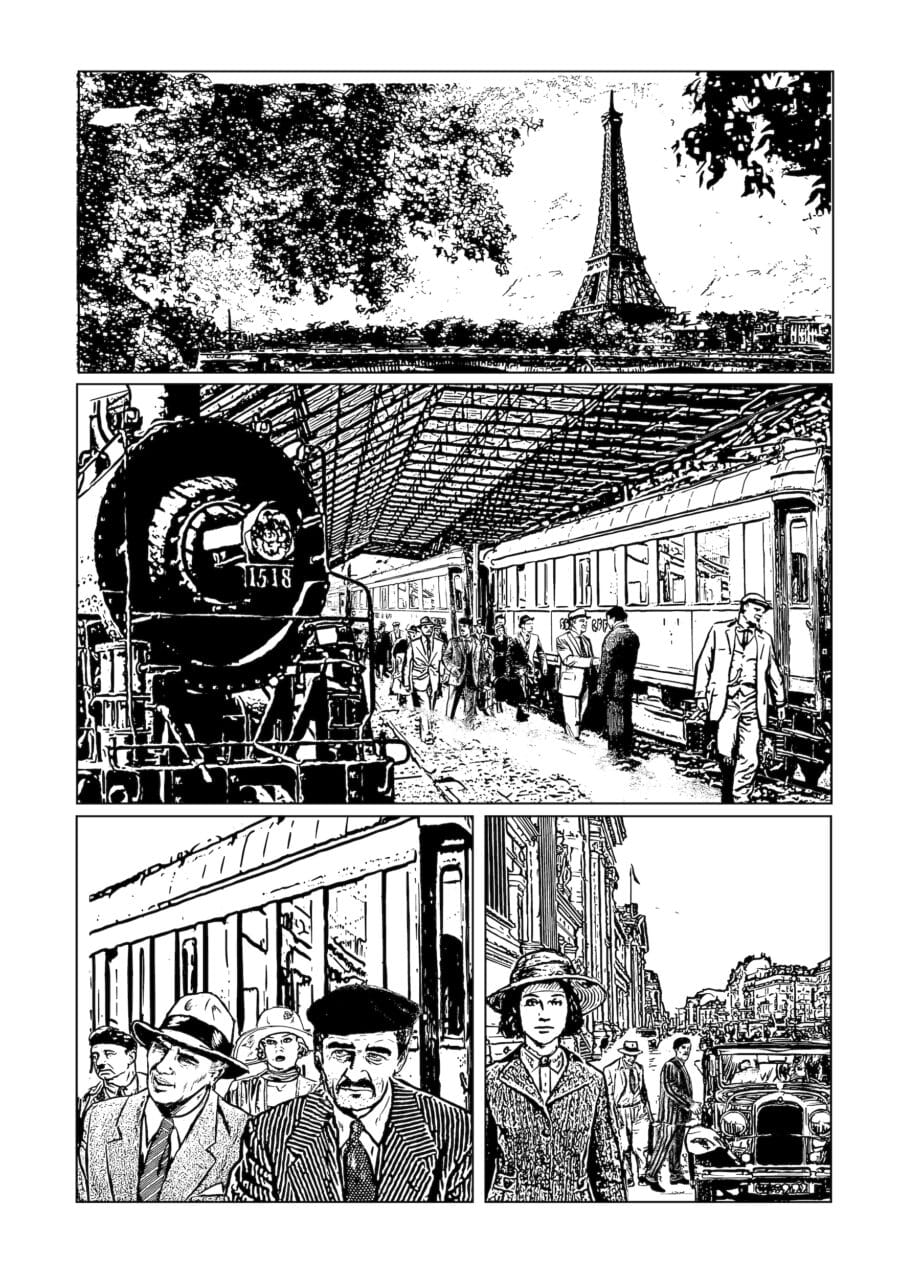

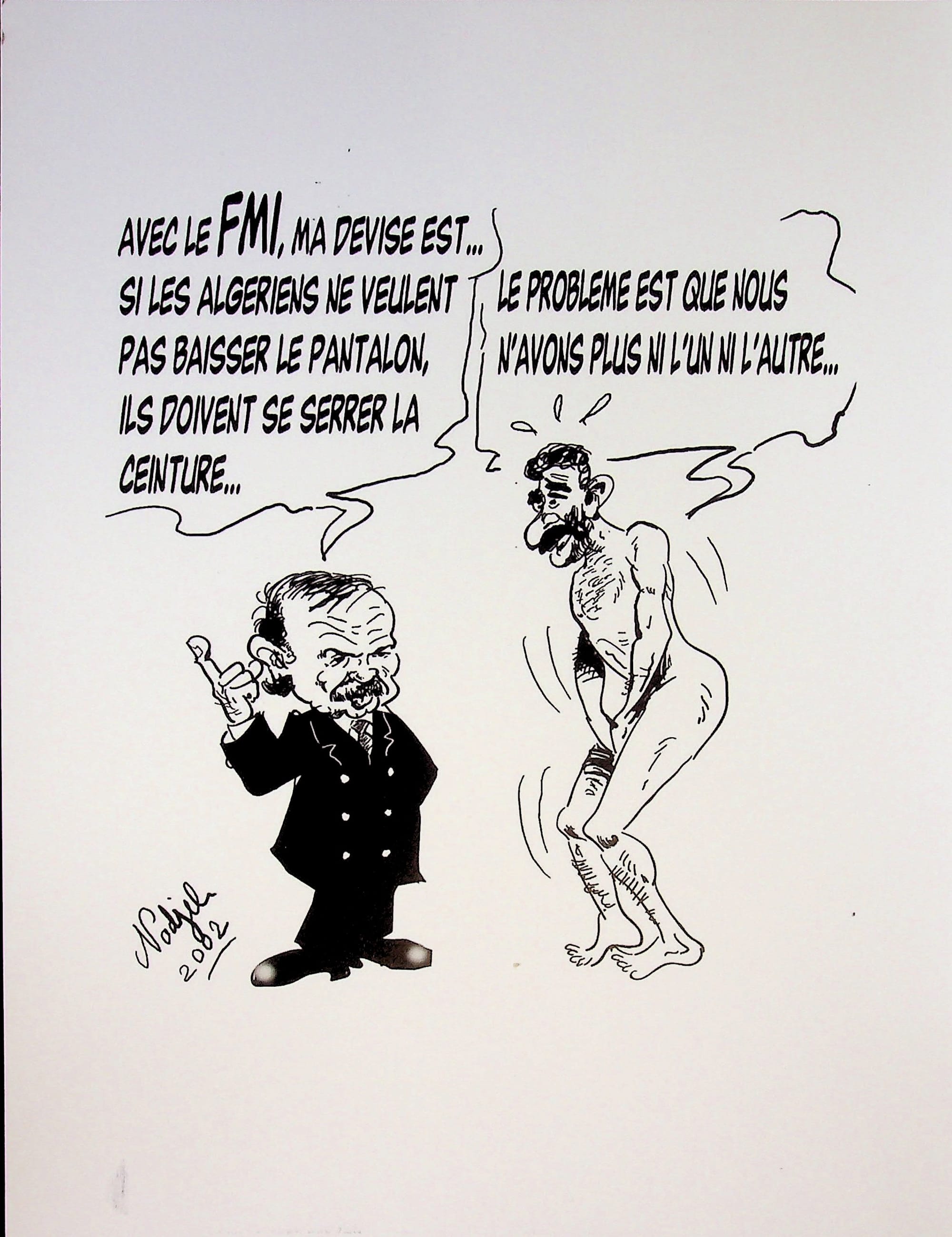

Aomar: Before I answer your question, it’s important for me to say why my collaboration with Nad was a perfect fit. Nad was born on October 16, 1952 in Tlemcen, Algeria and began drawing as an amateur in 1980s. He represents a second generation of Algerian artists who follow in the footsteps of Slim and Mohamed Dorbhane. In 1986 he published his first comics, La Poudre Magique (Magic Powder) and Les Pillards du Desert (Desert Raiders). Our collaboration was perfect because he had a strong understanding of North African history, Algerian society, World War II history, European history, French society and even the Holocaust. His father Sid-Ahmed Berber had been drafted into the French army as an Algerian tirailleur (infantry) and served on the Maginot Line. His uncles were wounded in the campaign to liberate Provence. He was a well-read artist with an excellent understanding of the French, American and North African schools of comics and graphic novels. Our objective was to track the journey of European refugees during World War II into our home countries of Algeria and Morocco. We were lucky because we were neighbors in Westwood, Los Angeles. We met regularly in person in cafés and our homes. Every week and sometimes every day we met to discuss and agree on sections of the plot before Nad worked on the panels and drawings. As we discussed the characters’ development, we researched carefully the social as well as the urban contexts, matching it with archival material that I had collected over 14 years. We knew from the beginning that a project about the North African camps would offer something different than the better-known stories of World War II camps in Europe and the United States.

Elizabeth:A good portion of the work’s beginning highlights relations between Muslims and Jews in France and North Africa. Why did you and Berber decide to use this space to address those relations?

Aomar: In the archives I encountered conversations between Jews and Muslims. These intellectual conversations partly revolved around the importance of a Muslim-Jewish partnership against anti-Semitism, racism and Islamophobia. Based on this fact, Nad and I strongly believed that in their labor, disciplinary and internment camps, Vichy authorities saw Muslims and Jews as “undesirables.” North African and West African indigenous groups were also defined as undesirables by Philippe Pétain’s collaborationist government. We wanted readers to see the impact of the Nazi and Vichy racial, political and economic policies on larger populations in Europe and the Mediterranean region. We see our graphic novel as part of what I call Mediterranean bande dessinée (comics) of mobility and migration (MED-BDM): an organic multinational artistic project with an educational orientation to evaluate colonial pasts and postcolonial relations between both sides of the Mediterranean landscape. As I conceptualize it, MED-BDM has the capacity to challenge deceptive, unrepresentative photographic reportage and journalistic writing of colonial photography.

Elizabeth:The beginning of the Undesirables brilliantly shows the intricate connections that existed between communities from different areas in Western Europe and North Africa. Why did you feel that it was important to start the work this way and in Germany in particular?

Aomar: Hans, the main character of the graphic novel, was a German Jew with Mediterranean connections. Through Hans, and relying on an archival thread of narratives and stories, Nad and I made an effort to retroactively create these social relations that start in Munich and take us to Berlin, Paris, northern Spain, Algeria and Morocco. By underscoring these connections, we make the case for what we see as a Mediterranean humanistic approach to war. Instead of focusing on the debate of whether the Holocaust took place in North Africa or not, we follow the trails of refugees across the Mediterranean to port cities in North Africa and then labor camps. By starting in and with Germany, we establish the fact that these human displacements were the result of racial and anti-Semitic policies drafted in Munich and Berlin and used to force Jews and other “undesirables” out of Europe.

Elizabeth: How do you convey what is in the archive through artwork and a narrative story that includes dialogue, which, while informed, does have to be imagined at least in its word-for-word format? Were there any points in the work where you had to speculate a bit as to how events occurred?

We see our graphic novel as part of what I call Mediterranean bande dessinée (comics) of mobility and migration... an organic multinational artistic project with an educational orientation to evaluate colonial pasts and postcolonial relations between both sides of the Mediterranean landscape.

Aomar: We used the medium of the graphic novel to reconstruct the narratives of undesirables held in Saharan Vichy camps by retrieving their written histories from various archives, rearranging them in the format of vignettes, panels and horizontal sequences. This mode allowed for the inclusion of direct speech of subjects taken from the archives and adapting them to the rounded speech balloons. Ethnographic commentary is included in square text boxes that highlight narrative voice-overs used to relay information to the reader. We contend that in the larger context of an anthropology of genocide and the Holocaust, a style of a Mediterranean graphic memoir connecting Europe and North Africa could be seen as a retroactive ethnographic account where witnessing takes place through seeing guided by the archive.

Elizabeth:Some of the characters in the work who speak or are mentioned like Si Kaddour Benghabrit (the first rector of the Grand Mosque of Paris) were actual historical figures while others are composite figures. How did you decide which voices should be included, and how did you go about trying to merge different voices and experiences from the archives into these characters?

Aomar: Every character in the book is a historical figure. The only difference is that some are known like Si Kaddour Ben Ghabrit and Bernard Lecache and others were not, like Hans and Nessim ben Nessim. That’s why our graphic work tries to give them an ethnographic voice while imagining how they looked. Even a composite character like Hans is in a large part real. Nad and I gave ourselves the license to imagine how the characters looked, behaved, acted and smelled. But our visual imagination is inspired by what it is in the archives. Therefore, it is not a novel; it is historical ethnography.

Elizabeth:The work does a fantastic job of demonstrating that, as in Europe, individuals of varying backgrounds ended up in the camps together as “undesirables.” Was it a challenge to develop characters or depictions that represent these diverse groups? Was it important to you and Berber to depict this diversity?

Aomar: We want to stress the point that Vichy’s undesirables were Jews, Muslims, Spanish Republicans, Communists, political dissidents, North African nationalists and West Africans. This was never a challenge to us because we followed their traces in the archives, which led us to this choice of representation. The archives we consulted (Yad Vashem, the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, family archives in Tata, southern Morocco and other private troves around the world) were full of these narratives and individual stories. We found out that in their colonial policies Vichy authorities did not make a distinction between Spanish Republicans and European Jews or North African nationalists and West Africans. While North African Jews were not included in the list of “undesirables” sent to labor camps, Vichy racial policies excluded them for education and other economic occupations and called for their return to their traditional neighborhood. Undesirables became a marker of distinction of anyone who did not fit what Vichy saw as real French.

Elizabeth: In Undesirables, we see nationalist activists being detained alongside Jewish and political prisoners in Algeria. Do we see evidence from the archives of these communities discussing their experiences of oppression or what relations were like between them?

Aomar: During and after World War II, prisoners and refugees, who were interned in many detention centers throughout the world, published memoirs about their daily lives behind barbed wire. In North Africa, refugees and prisoners who fled to French North African colonies following the German occupation of France were not allowed by Vichy guards to record the daily events of Saharan camps. For example, Max Aub, a well-known internee in the camp of Djelfa, wrote the entire Diario de Djelfa on the front and back of an 8.5cm x 13.4cm notecard because he was prohibited from writing during his internment in the labor camp. Others tried, but their notes were confiscated and destroyed by camp guards. In his memoir on the detention and disciplinary camp of Djenien-Bou-Rezg in south Oran between 1940 and 1943, Mohamed Arezki Berkani, who wrote the only surviving Muslim memoir about a Vichy camp in Algeria and Morocco, states that during their imprisonment they were not authorized to take notes about their lived experiences and the activities of the police force in the camps. Some militants took notes in Arabic or French, but they were forced to burn them later. This shortage of autobiographies written during the war could also be attributed to what Claudine Kahan terms the “shame of eyewitness.” Psychological studies argue that survivors of traumatic events struggle to report the sadistic treatments of their guards and torturers. Despite all these challenges I was also able to collect stories from native North African Muslims like my father who experienced the war. My colleague Sarah A. Stein and I were able to write about these diverse Muslim narratives in Wartime North Africa: A Documentary History: 1934-1950 (Stanford University Press, 2022).

Elizabeth: How was the experience of working on this graphic novel different from writing nonfiction scholarship?

Aomar: Working on this graphic novel was as labor intensive as any nonfiction scholarship if not more. We had to consult thousands of documents. We had to check the stories to make sure that they communicated the ethnographic dimension of the graphic novel that we wanted to communicate. At the same time, we had to think like a scriptwriter treading carefully around the borders of fiction. We wanted to make sure that the frame we present is different from traditional frames of previous Holocaust comics and graphic novels. As a historical anthropologist, I had to adjust to Nad’s artistic vision. I was fortunate because I had an undergraduate background in directing and scriptwriting. I was able to draft the script based on suggestions from Nad.

Elizabeth: I have looked more at Berber’s art when he produced caricatures and albums under the name of Nad in Algeria and Tunisia, and his style here diverges from his earlier style and appears to mirror artwork from the 1930s and 1940s (one reviewer of the book also noted its resemblance to noir cartoons of the period). Was this a deliberate choice?

Aomar: Yes, the choice we made here was a very conscious decision to produce a graphic history close to realism. We wanted to take readers back to the period between the 1920s–1940s. We wanted it to feel like we are reporting the journey of Hans in real times as ethnographers do.

Elizabeth:As someone who frequently teaches the history of the Holocaust in Maghribi and world history courses, I was excited to hear about the work’s publication and to have a new tool for teaching students about this critical subject. While students often come to the table with a solid understanding of the Holocaust in Europe, very few are aware that it also took place in North Africa. Would you have any advice for instructors who plan to use Undesirables in their classes?

Aomar: I would make sure that students are introduced to the complex colonial structures in North Africa before I assign the book. Once Students understand the dynamics and nature of French, Spanish and Italian colonialisms in North and West Africa, then they will be able understand why it is important to read World War II through these Mediterranean connections. Our graphic novel will make it easy for any classroom on Holocaust Studies or World War II to visualize the theoretical and conceptual notions of race.

Elizabeth: What are you working on at the moment? Do you have any plans for additional graphic novels in the future?

Aomar: I am currently collaborating with Daniel Schroeter on a historical and ethnographic manuscript that deals with the story of Mohammed V saving Jews during World War II. In the last few years, I have carefully watched my daughter and her friends’ reading habits. Comics and bande dessinées dominated their choice. I am planning a number of short graphic novels in the future about topics related to my North and West African research. Also, Nadjib left an incomplete project based on the history of the Assassins that he requested that I finish in the coming years. This incomplete graphic historical novel traces the history of inter-religious conflict through the case of the Assassins. My collaborative project with Nadjib is a testimony of his strong belief in the possibility of a North African school of bande dessinée which includes artists and social scientists. Undesirables is a testimony of Nadjib’s North African collaborations, which started with Tunisians in the 1980s and continued with Moroccans such as Abdelaziz Mouride and myself in the 2000’s.