A bridge over the Shatt al-Arab river, formed by the confluence of the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers, in the southern Iraqi city of Basra. (Hussein Faleh/AFP via Getty Images)

Proponents of federalism, like the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), saw it as a panacea that would resolve the crisis of public services and protect sub-national identities. Its opponents, however, believed it would deepen divisions in an already fragmented country and serve as a tool of separation.

Supporters of federalism won, at least on paper. In 2005, it was enshrined in Iraq’s constitution. But 20 years on, the system has proven stagnant.

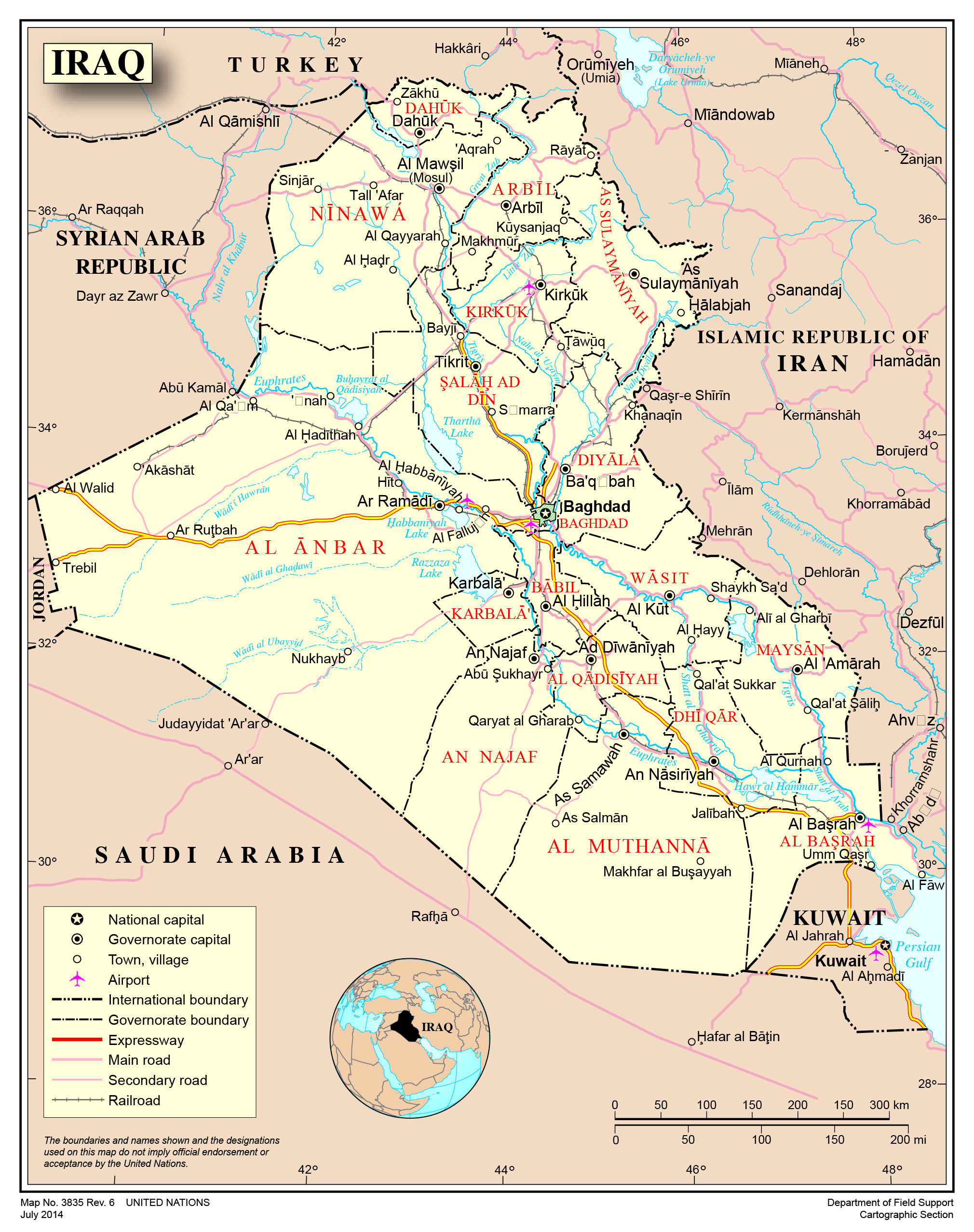

Today Iraq is comprised of 18 governorates. But only three of them—Duhok, Erbil and Sulaymaniyah—are incorporated into an autonomous region, Iraqi Kurdistan, with its own parliament, sub-national ministries and a regional president. The other 15 governorates maintain a centralized relationship with Baghdad, although each has a governor and a provincial council. Those governorates that attempted to form their own region over the past two decades have faced various obstacles from both the central government and Iraqi Kurdistan, ensuring that any promises of federalism remain uneven and unfulfilled.

Making Iraq Federal

The push for Iraqi federalism predates 2003. In 1991, the nine Shi’i majority governorates south of Baghdad, plus the governorates of Iraqi Kurdistan and Kirkuk, rebelled against President Saddam Hussein and his ruling Baath Party. The uprisings were sparked by the defeat of the Iraqi army in the Gulf War and the accumulated economic and political grievances within the Shi’i and Kurdish communities, who were persecuted under Baathist rule. The northern no-fly zone established by the United States over the Kurdish governorates enabled a degree of political autonomy, and the region was able to establish independent political institutions. Despite a southern no-fly zone, Iraq’s Shi’a continued to live under Baathist repression and reprisals for 12 more years.[1]

Federalism continued to be an important issue for many of Iraq’s exiled opposition leaders, like Jalal Talabani and Ahmed Chalabi, after 1991. They repeatedly addressed the issue in conferences organized in the United States and Iraqi Kurdistan.[2] Saddam Hussein’s campaign of ethnic cleansing against Iraq’s Kurds bolstered their drive for statehood. Surrounded by countries that have contentious relationships with their own Kurdish populations, however, Iraqi Kurds were only able to push for self-governance within the parameters of a federal Iraq. The United States, in the lead up to the 2003 invasion and afterwards, also prioritized a one Iraq policy, in part to appease their NATO ally Turkey.

In January 2005, elections were held to select members of a committee to write a new constitution. The Iraqi political parties who were engaged in the process acknowledged a special status for Iraqi Kurdistan and agreed to carve out a distinct federal entity within Iraq that would have constitutional recognition. But they could not agree on whether the remaining governorates should be allotted similar status.

Most of the Shi’i opposition parties, for example, did not support federalism outside of Iraqi Kurdistan. These parties believed that centralized democracy afforded the Shi’a, Iraq’s demographic majority, the assurance that they would not be oppressed by minority rule again, as had been the case under Baathist rule. One exception was the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI)—an Islamist party that was established in exile in Iran and was able to forge close ties to Kurdish parties. In 2005, SCIRI proposed the establishment of one region encompassing the nine Shi’i majority governorates south of Baghdad, an effort that was ultimately unsuccessful.

Meanwhile, Kurdish parties, like the KDP and PUK, also influenced the drafting of the constitution. These parties supported a federal Iraqi state that would recognize Iraqi Kurdistan as a region but also leave the possibility open for other governorates (except for Baghdad) to become regions.

The final constitutional document—ratified in October 2005—established a federal system “made up of a decentralized capital, regions, and governorates, as well as local administrations.”[3] Article 117 recognized Kurdistan as an official region but only within the nation of Iraq. The constitution also provided for the creation of new regions. Article 119 established two methods for a governorate to hold a referendum on becoming a region—gather signatures from 10 percent of the governorate’s voting population or get the approval of one-third of the provincial council members. In both cases, the Independent High Electoral Commission—a body established in 2004—must be involved in the referendum and in coordinating the collection of signatures.

No New Regions

Several governorates attempted to regionalize during former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki’s eight years in office between 2006 and 2014, but none of these efforts met with success.

In 2008, for example, the most serious effort to regionalize Basra was led by its former governor, Wael Abdul Latif. By then it was clear to the citizens of Basra that although their governorate produced most of Iraq’s oil wealth, it was underdeveloped, especially in contrast to Iraqi Kurdistan (also rich in oil as well as an autonomous region). Many citizens and local leaders believed that federalism would empower Basra to use its resources to improve its residents’ standard of living by providing better services and governance. But the effort was met with resistance from the Independent High Electoral Commission, which Abdul Latif accused of employing tactics to discourage people from supporting a referendum. For example, the Commission opened only a fraction of the voting centers needed for a governorate as large as Basra.

Iraq with governorate boundaries. Map by the United Nations.

Abdul Latif believes the Commission was influenced by politicians in Baghdad who feared that increased autonomy in Basra would hinder Baghdad’s ability to govern.[4] Baghdad was wary of losing fiscal resources if the Basra region were to control its own oil revenues, as has been the case at times in Iraqi Kurdistan.

At present, Basra continues to push for federalism, sometimes as its own region and other times in coordination with the southern governorates of Maysan and Thi Qar. Those calling for regionalism in Basra have made it clear that they oppose the breakup of Iraq and are not looking to replace Baghdad.

Other governorates like Diyala and Salahuddin in central Iraq were also prevented from holding a referendum during Maliki’s time in office—even after more than a third of their provincial council members voted for one in 2011.[5] The major Shi’i political parties, including Maliki’s Islamic Dawa Party, opposed the regionalization of these governorates even though one of the parties, the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq, formerly SCIRI, had itself tried to form a region. Political leaders in Baghdad claimed that the push for a region in Diyala and Salahuddin would weaken the federal government. They also rejected holding a referendum on the grounds that it was motivated by sectarianism (the two governorates are majority Sunni). Salahuddin’s vote against adopting the constitution in 2005, followed by its attempt to utilize Article 119 to push for a region six years later, only added to this impression.

Another obstacle preventing Diyala and Salahuddin from holding a referendum was that both governorates include territory considered to be disputed between the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and the federal Iraqi government. While the constitution only names Kirkuk among the disputed territories, the KRG considers parts of Nineveh, Diyala and Salahuddin to belong to Iraqi Kurdistan, citing historical claims that predate Baath displacement policies. These claims are contested by local non-Kurdish populations who have struggled to maintain balance between Baghdad and the KRG.[6]

The issue of disputed territories has been a thorn in relations between the federal government and the KRG. The 2005 constitution stipulated that a referendum be held by December 31, 2007, to determine the status of Kirkuk and other disputed territories. But as of March 2023, no such vote has taken place. Indeed, Iraqi policymakers are caught up in a legal debate on whether this issue still needs to be resolved at all, or whether the fact the deadline has passed means it is no longer relevant.

Disputed areas like Kirkuk, the Nineveh Plains and Sinjar have suffered over the years due to neglect from both the federal government and the KRG. Meanwhile, pathways to change are limited. Kurdish parties fear that, if given the choice, these disputed territories would form a separate region rather than join Iraqi Kurdistan. For the larger districts, like Sinjar or Talafar, the first step is to become a governorate, which requires cabinet and parliament approval. In the case of Kirkuk, which is a governorate, it can legally form its own region through Article 119, but it too is likely to face pushback similar to that experienced by Diyala, Salahuddin and Basra.

The Future of Iraqi Federalism

Despite the push for federalism from the KDP, PUK and ISCI, there have been no changes to Iraq’s federal composition other than the enshrinement of Iraqi Kurdistan as a region in the constitution.

Those who fear federalism view it as being one step away from separatism. These concerns were reinforced by the independence referendum in Iraqi Kurdistan on September 25, 2017, which was also held in the disputed territories. Although it was rejected by Baghdad and the KRG later claimed the referendum to be non-binding, it nevertheless cemented the belief among many Iraqis that becoming a region is the first step toward independence.

Beyond the political obstacles and resistance by the central government to give up control over revenue-generating resources, Iraq lacks the institutions for decentralized governance. Even when Iraq’s prime ministers have pushed to decentralize certain federal ministries—as did Haider Al-Abadi with several ministries between 2014–2018—either the governorates struggled with the responsibility or the ministries in Baghdad refused to delegate power.[7] Moreover, until the relationship between Baghdad and Iraqi Kurdistan is stable and long-standing disputes are resolved, it is unlikely that other regions will be able to form.

[Hamzeh Hadad is an adjunct fellow at the Center for a New American Security and a visiting fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations.]

Endnotes

[1] Marsin Alshamary & Hamzeh Hadad, “The Collective Neglect of Southern Iraq: Missed Opportunities for Development and Good Governance,” International Peacekeeping, February 2023.

[2] United States Department of State, “The Future of Iraq Project,” November 2002.

[3] Iraq’s Constitution of 2005. Available in English at constituteproject.org.

[4] Author interview with Dr. Wael Abdul Latif in Baghdad, April 18, 2022.

[5] Joel Wing, “Push To Make Iraq’s Diyala Province An Autonomous Region Fades,” Ekurd Daily, December 30, 2011.

[6] Shamiran Mako, “Negotiating Peace in Iraq’s Disputed Territories: Modifying the Sinjar Agreement,” Lawfare, January 17, 2021.

[7] Ali Al-Mawlawi and Sajad Jiyad, “Confusion and contention: understanding the failings of decentralisation in Iraq,” LSE Middle East Centre, 2021.