This article is available in Arabic as part of a collaboration between MER and the independent Iraqi media initiative Jummar.

In October of 2019, Iraq witnessed what was likely the largest popular protest in its modern history. Two relatively minor events—a heavy-handed response to a small protest of university graduates and the demotion of a popular general—triggered long-standing discontent at the political system that had periodically led to mass protest in the past.

Image of a protester and the Turkish restaurant building in Tahrir Square, Baghdad, designed by Atef Al-Jaffal/Jummar.

Tens of thousands of Iraqis took to the streets in the capital and across the provinces of the south. Protesters occupied public squares for six months, in some cases longer. What became known as the Tishreen (Arabic for October) protests were widely celebrated in Iraq and abroad for their tenacity, their commitment to peaceful means, their espousal of civic nationalism and their rejection of the political system and ethno-sectarian politics. The protests were also mourned, not just for ultimately failing to alter the fundamentals of the political system, but for the 600–800 young Iraqis who lost their lives in the ensuing government crackdown, particularly between October and January.

Since 2019, protest culture has become ubiquitous in Iraq, especially in Baghdad and the other Shia-majority areas of the country that were the site of the Tishreen protests. Demonstrations are regularly organized for a variety of reasons. Some seek to keep the spirit of 2019 alive. Others are for government jobs. Some protests are responses to specific political or economic issues (the devaluation of the dinar, gender violence, the arrest of political activists or the burning of the Quran in Sweden—to name a few recent examples). Others are shows of force organized by political elites. The last in particular has become more common since 2019, with the political classes appropriating protest culture in order to blunt the effect of anti-systemic protest activism and as a tactic in intra-elite competition.

The scale of the protests of 2019 narrates the failure, in Iraq, to build a functioning and representative state from the wreckage of 2003. Yet the survival of the system and the deflation of what, at the time, seemed like unstoppable popular momentum reflects the resilience of the political system that has emerged over the course of the last two decades.

The Tishreen Protests

Since 2011, and more so since 2015, mass protests in Iraq have been a near yearly occurrence.

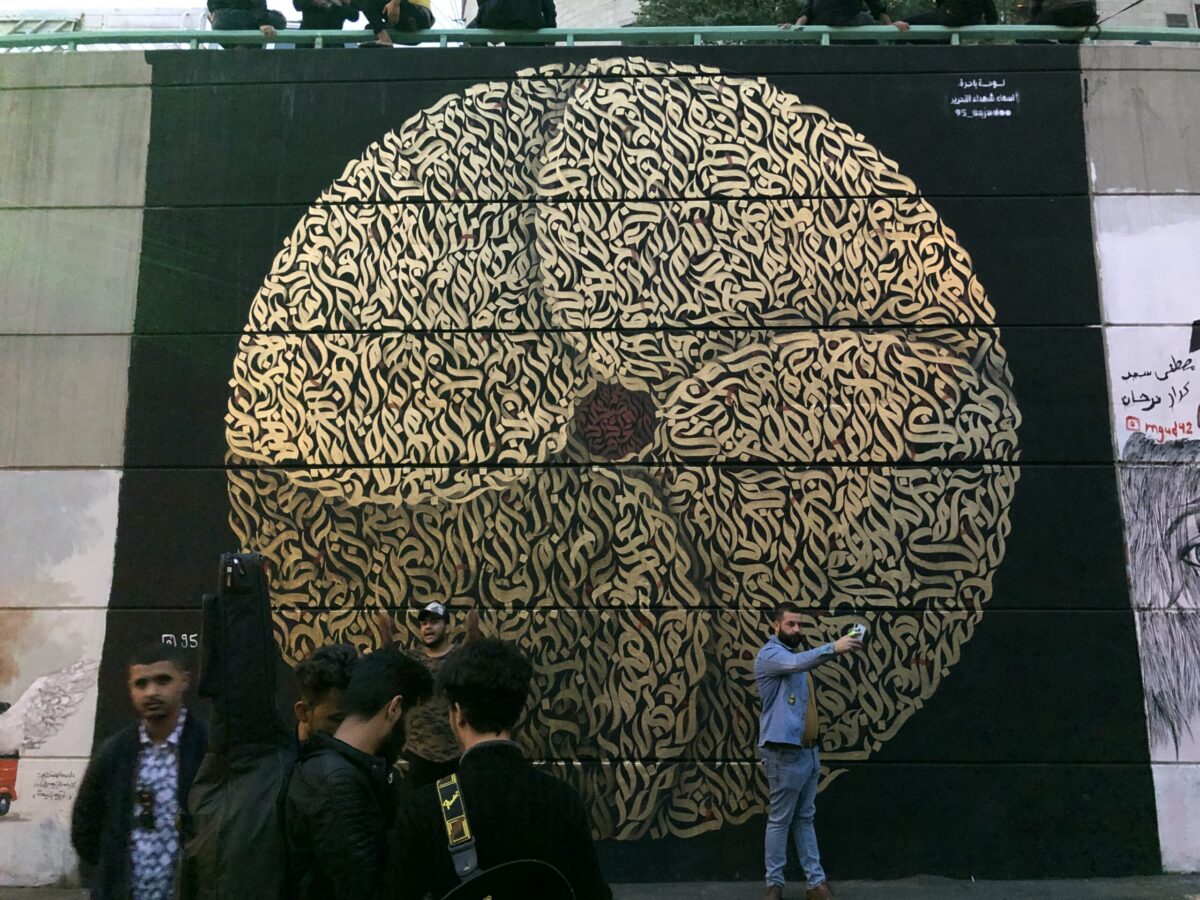

A Tishreeni mural from Tahrir Square, Baghdad. Photograph by author.

The reasons why are well known to observers: anger at the looting of the state by the political classes and their affiliates, anger at widespread economic and political disenfranchisement, anger at the Iraqi state’s subservience to foreign interests, anger at the failures of public services and state institutions and anger at having to suffer seemingly inescapable poverty in what on paper should be a rich country. Beginning in 2015, these grievances, rather than identity based or sect-specific grievances, became the primary basis for protest mobilization.[1] With the exception of 2011, protests prior to 2015 had often had a basis in identity politics as was the case with the mass mobilizations in Sunni-majority provinces in 2012–2013.

The most significant protest outbursts since 2015 have been in Shia majority parts of Iraq. Other parts of Iraq have followed different protest cycles. Protests in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq have been chiefly concerned with the failings of the Kurdistan Regional Government and have faced severe crackdowns by regional security forces.[2] There have been sporadic protests in Sunni areas, including a few symbolic demonstrations of solidarity with Tishreen in 2019.[3] But a combination of intimidation, fatigue and, for some, a view that Tishreen is an intra-Shia affair, restricted the 2019 protests to Shia-majority areas of Iraq, thereby preventing the Shia political classes—the dominant actor in Iraqi politics—from playing the sectarian card to shore up the political system. This tactic, which was used during the protests of 2012–2013, is one employed by regimes across the region when confronted by protests that are susceptible to sectarian othering as was vividly demonstrated by regime responses to the uprisings of 2011 in Syria, Bahrain and Saudi Arabia.

A Tishreeni mural from Tahrir Square, Baghdad. Photograph by author.

As the cumulative result of protest activism since 2015 (if not 2011), what emerged in 2019 was unprecedented in scale. In addition to their size and longevity, the Tishreen protests crossed ideological lines and transcended boundaries of class, age, profession and gender. Though the bulk of the protesters were young working-class Shia men, broadly reflecting the demography of the regions involved, women’s groups, student activists, non-Shias and a variety of age groups demonstrated alongside them. In that sense, these protests happened to be Shia-majority rather than being sect-coded Shia protests. Indeed, the protests embodied an explicit rejection of the system in its entirety and particularly of ethno-sectarian politics and foreign interference. The result was a remarkable, and in some cases beautiful, articulation of the ideals that previous protests had championed and that Tishreen perfected.

The protests of 2019 achieved some victories. The government, led by Prime Minister Adil Abd al-Mahdi, was forced to resign and a new election law drafted. The law, and in particular its expansion of electoral constituencies, helped diminish the electoral fortunes of many established political actors, particularly the Iran-affiliated wing of the Shia political establishment. The new law also provided some modest electoral openings in the October 2021 elections for first-time candidates, including some affiliated with the protest movement.

Protest after Tishreen—Between Appropriation and Memorialization

Another of Tishreen’s successes was its creation of a new protest culture. But the ubiquity of protest has blunted its effect, sowing doubt in public opinion as to which protests are genuine and which are orchestrated by political elites for their own ends or as a show of force. For example, in December 2022 protests broke out in the southern city of Nasiriyah over the imprisonment of an activist, resulting in two deaths. In the aftermath, accusations quickly arose online and in Iraqi media that the protests were staged for private gain. Specifically, it was alleged that people with no relation to Tishreen had taken to the streets pretending to be Tishreenis who had been wounded in 2019 in order to claim government compensation. Others claimed that provocateurs had been paid by political factions to escalate unrest during the protests.

The November 2020 Sadrist demonstration at the Turkish restaurant. Photograph by the author.

The fact that so many now claim to speak in the name of Tishreen complicates Iraqi public opinion toward protest activism. This problem is compounded by the political classes’ appropriation of protest culture. Members of the political elite mobilize supporters or simply use rent-a-mobs to undermine their rivals and to mount shows of force. Long a tactic of the Sadrists who routinely mobilized their unparalleled political base to assert their will, in recent years this practice has been employed by other political factions including the Sadrists’ rivals.

For example, since 2019, political actors aligned with Iran have repeatedly staged demonstrations of their own. They did so in 2020 after the assassinations of Qasim Suleimani, the Iranian Quds Force commander, and Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, the Deputy Chief of the Popular Mobilization Units (PMU—the umbrella organization of parastatal units led by Iran-leaning political actors). In 2021 they protested again to challenge unfavorable election results, and the assembled protesters spoke in language similar to that of Tishreen: reclaiming stolen rights, honoring martyred protesters and railing at the political system. Similarly, in the summer of 2022, Tishreeni symbolism was on display at Sadrist protests against rival Shia actors as the two sides fought over the government formation process. Pictures were held up of Safaa Al Saray, a young activist whose image turned into a Tishreeni icon after he was killed by security forces in October 2019.

Safaa Al Saray

The blurring of the distinction between elite-driven and popular protest has proven highly effective for political actors wishing to penetrate protest movements and sow doubts about their credibility. It was a tactic witnessed early on in Tishreen. As one former protest activist put it in an interview, the Tishreen protests had three types of protester: There were, in his eyes, the “genuine” Tishreen protesters, people who were not getting paid to protest and had no ulterior motives; the political fronts established by the ruling political parties and embedded in protest sites to monitor and distort the course of events; and the opportunists—protesters who offered their services to the highest bidder. This proliferation of protester types blunts the efficacy of protest as a vehicle for effecting meaningful change.

In many ways, the Tishreen protesters have become victims of their own renown. The immense symbolic significance generated in 2019 has often been counterproductive thereafter, with protest activism at times prioritizing memorialization over the development of political action. This feature has been particularly evident at the annual commemorations of Tishreen and in the anchoring of much oppositional discourse in the events of October 2019. Memorialization is a natural concomitant to events such as Tishreen especially given the lives that were lost, but a fixation on memorialization can arguably serve to freeze a movement in a hallowed moment, preventing forward momentum. Put another way, does memorialization in and of its own pose a challenge to the system? Unless it inspires further action—new protest repertoires, new forms of organization and the like—memorialization will remain an act of symbolic and emotional significance with little political potential. Iraqi history is replete with momentous, painful and emotionally significant events. Memorialization ensures that Tishreen is added to the dimly remembered list alongside the Amriyah massacre, the rebellions of 1991, the Battles of Fallujah or the carnage that swept through Baghdad in 2006, to name just a few examples. Alone, it promises little else.

The Turkish Restaurant

The Turkish restaurant during Tishreen. Photograph by the author.

The excessive focus on memorialization also opens up circuitous debates as to the true owners of an event and encourages the appropriation of its symbols for political gain. At Tahrir Square, the epicenter of Tishreen, stands one of Baghdad’s few high-rises, a derelict 14-story building referred to by locals as the Turkish restaurant (it once housed a Turkish restaurant). At the start of Tishreen in October 2019, government surveillance and snipers (most likely from state-affiliated paramilitary groups) used the Turkish restaurant to suppress protesters. In mid-October protest activism was suspended due to a religious festival. When the protests resumed in late October, protesters were quick to occupy the Turkish restaurant to deny the government the strategic use of the building. In doing so, the protesters transformed the Turkish restaurant into an emblematic icon of Tishreen. Draped with protest banners and artwork expressing the ideals of the gathering protest movement, it effectively turned into the most visible billboard for the expression of protest sentiment.

Some of the protesters’ artwork remains on the building today, but for the most part it has returned to being a nondescript part of Baghdad’s drab skyline. It is currently occupied by official and Sadrist security forces to prevent it from reverting to a protest site in the future. The building has also become part of the contested symbolic landscape of Baghdad’s urban space. Political elites have sought to enlist the symbolic significance that it acquired in 2019 in their rivalries with one another and to assert their own power. For example, in November 2020, shortly after the final clearing of protesters from Tahrir Square, followers of Muqtada al-Sadr were mobilized by their leader to assert Sadrist dominance in protest squares formerly affiliated with Tishreen. In doing so, and true to the precedent set by Tishreen, Sadrists draped the Turkish restaurant with giant banners displaying their own iconography (see photo in previous section). By helping to evict the protesters and by appropriating the Turkish restaurant in this manner, the Sadrists were signaling their street power and attempting to claim ownership of mass mobilization.

Hashd commemoration in Tahrir Square of the first anniversary of the assassination of Abu Mahdi al Muhandis and Qasim Suleimani. January 2021. Khalid Al-Mousily/Reuters

In another example of the appropriation of Tishreen’s protest repertoires by other political actors, including Tishreen’s adversaries, in January 2021 the PMU used the Turkish restaurant to commemorate the one-year anniversary of the assassination of Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis and Qasim Suleimani. The building’s 14 stories were covered, in Tishreeni fashion, with images of Muhandis, Suleimani and other fallen figures alongside a number of Iraqi flags.

The former Prime Minister of Iraq, Mustafa al-Kadhimi also sought to enlist the symbolic value of the Turkish restaurant and of Tishreen itself. In mid-2021 the ever-changing facade of the Turkish restaurant was adorned with a billboard announcing the forthcoming transformation of the building into the Tishreen Museum, “with the support and sponsorship of the Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi.” The message was one of solidarity and sympathy with Tishreen, an attempt by the Kadhimi government to articulate and draw legitimacy from the now discredited notion that it was a product of the 2019 protests.

Banner on the Turkish restaurant announcing the forthcoming Tishreen Museum. Photograph by the author.

The Tishreen Museum announcement was met with objections from protest activists and their affiliates. One organization affiliated with Tishreen, al-Bayt al-Watani, protested that, “the demands of the political uprising and of the people have not been fulfilled, and it is too early to speak of establishing a museum to eternalize Tishreen because Tishreen has not ended.”[4]

The museum never saw the light of day and the banner was eventually removed. The official reason given for the project’s abandonment was that the building is the subject of ongoing legal proceedings between the Baghdad Mayoralty and private investors and that nothing can be done with it until the matter is settled. But its appropriation and the backlash it generated illustrate the complications inherent to the politics of memory.

A State of Perpetual Protest

For all that was impressive and admirable about the 2019 protests, there has been a tendency for supporters to overly romanticize them. The fact remains that 2019 failed to alter the fundamentals of the Iraqi political system. Indeed, it is these fundamentals that allowed the system to weather the storm of 2019. To understand the decline of Tishreen is therefore to understand the nature of the Iraqi state.

The destruction of the Iraqi state, beginning with the sanctions regime in 1990 and culminating with the invasion of 2003, was not followed by a coherent state building process. Rather, what was billed as the new Iraq was pieced together from the detritus of the former regime. A new political elite, various political entrepreneurs and economic predators, in addition to foreign interests, grafted themselves onto the broken structures of the Baath-era state. What emerged was a hybrid entity riddled with contradictions and governed by an oligarchy of formal and informal actors who collectively make up the state. The visage of the Weberian state—ministries, state institutions and so forth—conceals a reality of political penetration and capture of state institutions by the principal powerbrokers of Iraq. The relations of power and vested interests that underpin the system make it incapable of reforming itself. It is this reality that the promise of the protests of 2019 crashed against. The system’s ostensible tools for reform—its judiciary, its institutions and its bureaucracy—are subject to the same logic and to the same relations of power that the protesters were targeting.

The lack of meaningful change following 2019 showed that in the face of mass mobilization, the political system’s individual sources of weakness can be collectively a source of strength. Its oil-dependent rentier economy means that a critical mass of Iraqis are dependent on the system and therefore tolerant of it. That power is diffused through multiple patronage networks amplifies this dependence and makes revolutionary change all the more difficult: with no leading party to overthrow, no king to dethrone, no statue of Dear Leader to topple. Moreover, the elite collusion that underpins this diffusion of power naturally works to the system’s advantage. There is no formal parliamentary opposition and the political classes’ desire to maintain the empires they have built with state resources and through state institutions—the need for self-preservation—outweighs their incessant internecine squabbles.

Beyond elite networks, the flaws in Iraq’s electoral system render the ballot box ineffective as a tool for systemic change.[6] The weakness of Iraq’s institutions, its broken sovereignty and the weakness of the rule of law likewise work to the system’s advantage as it facilitates the use of extra-legal violence and external support. Indeed, elements of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard, including Quds Force commander Qasim Suleimani, are believed to have helped quell the uprising of 2019. In these and other ways, the Iraqi system creates strength through weakness when confronted by outbursts of popular discontent.

As predicted by many in 2019, the system was likely to endure and protest was likely to recur. Today, protest has become a permanent fixture of the political landscape, but it is no longer unidirectional. Protests are mounted against the system, against the government of the day, in pursuit of government jobs, by political elites and by their opponents. How long this state of affairs can continue is an open question. It is fashionable to declare that iniquitous contexts are unsustainable. Yet the post-2003 system has repeatedly demonstrated its resilience. Until the sources of that resilience are exhausted or otherwise made redundant, there is no reason to assume that fundamental change is on the horizon. Venezuela and Lebanon have suffered far worse without succumbing to systemic collapse, and Iraq still has some way to go before it finds itself in a comparable situation to either. Iraq’s vast resources and the international buy-in it enjoys sustain the fundamentals of Iraq’s political economy, even if occasional alterations and improvements are achieved in certain areas, as has happened in Iraq’s security and foreign relations over the past decade.

The prospect of perpetual protest, both elite-driven and popular, alongside persistent state failure is a damning indictment of the post-2003 state-building enterprise. It recalls former Finance Minister Ali Allawi’s summation of the Iraqi state in his lengthy resignation letter of 2022. He describes a state that exists in form but not in substance, one that is capable of recreating itself despite its numerous contradictions. It is these contradictions, underpinning the hybridity, the opacity and the dysfunction of the system, that paradoxically lend it resilience:

All the calls for reform are stymied by the political framework of this country… It has allowed for the state’s capture by outside interest groups. Unlike human beings, states do not die in a definitive way. They could linger on as zombie states . . . the machinery of government continues, it is true, and the trappings of state power persist, but there is no substance to the form.[7]

[Fanar Haddad is assistant professor of Arabic Studies at the University of Copenhagen.]

Endnotes

[1] Faleh A. Jabar, “The Iraqi Protest Movement: From Identity Politics to Issue Politics,” LSE Middle East Centre papers series 25, 2018.

[2] Murat Sofuoglu, “Why protests are raging across Iraq’s Kurdish region,” TRT World, 14 December, 2020, https://www.trtworld.com/magazine/why-protests-are-raging-across-iraq-s-kurdish-region-42357

[3] Balsam Mustafa, “All About Iraq: Re-Modifying Older Slogans and Chants in Tishreen [October] Protests,” Journal of Asian and African Studies, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00219096211069644.

[4] Shahad Musa, “Mathaf Tishreen, mashru’ tawthiq intifadha intaha bi lafita mutahari’ah,” Jummar, 01 October 2022, https://jummar.media/1749 .

[5] Ibid.

[6] Victoria Stewart-Jolley, “Iraq’s Electoral System,” Chatham House, Middle East and North Africa Programme, October 2021.

[7] Ali Allawi’s Resignation Letter is available at Shafaq ( 1660672630695()20220816192053.pdf (shafaq.com)