The Jazira’s Long Shadow over Turkey and Syria

In September of 2019, Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan called for the United Nations to establish a security zone in northern Syria east of the Euphrates. If the line extended south to Raqqa and Deir ez-Zor, he suggested, some 3 million Syrian refugees could be resettled not only from Turkey but also from Europe. The following month, American forces withdrew from parts of northern Syria and the Turkish military invasion—dubbed “Peace Spring”—began. In late October, the state news agency TRT featured Erdoğan speaking beside a map of the operation all across northern Syria. The president argued that Arabs belonged there and Kurds did not, “because it is a desert.”[1]

The statement invited several questions, among them, what does being Arab have to do with the desert? Is northern Syria—arid, to be sure, but also the most agriculturally productive Syrian lands—really a desert? And is the land all that different from the area just to the north of the border in Turkey? Behind these dizzying misrepresentations, however, was a clear aim: to send Syrian refugees in Turkey back while also neutralizing the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (also known as Rojava), which Turkey views as being dangerously close with the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK).

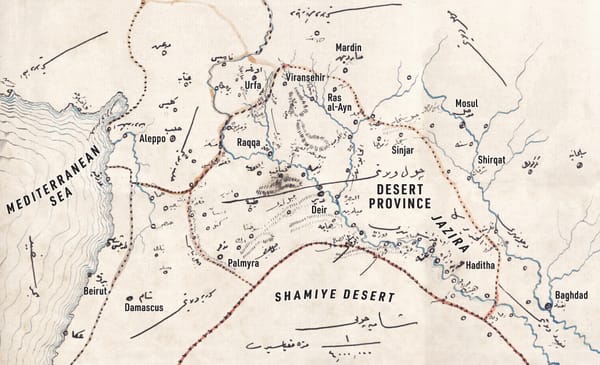

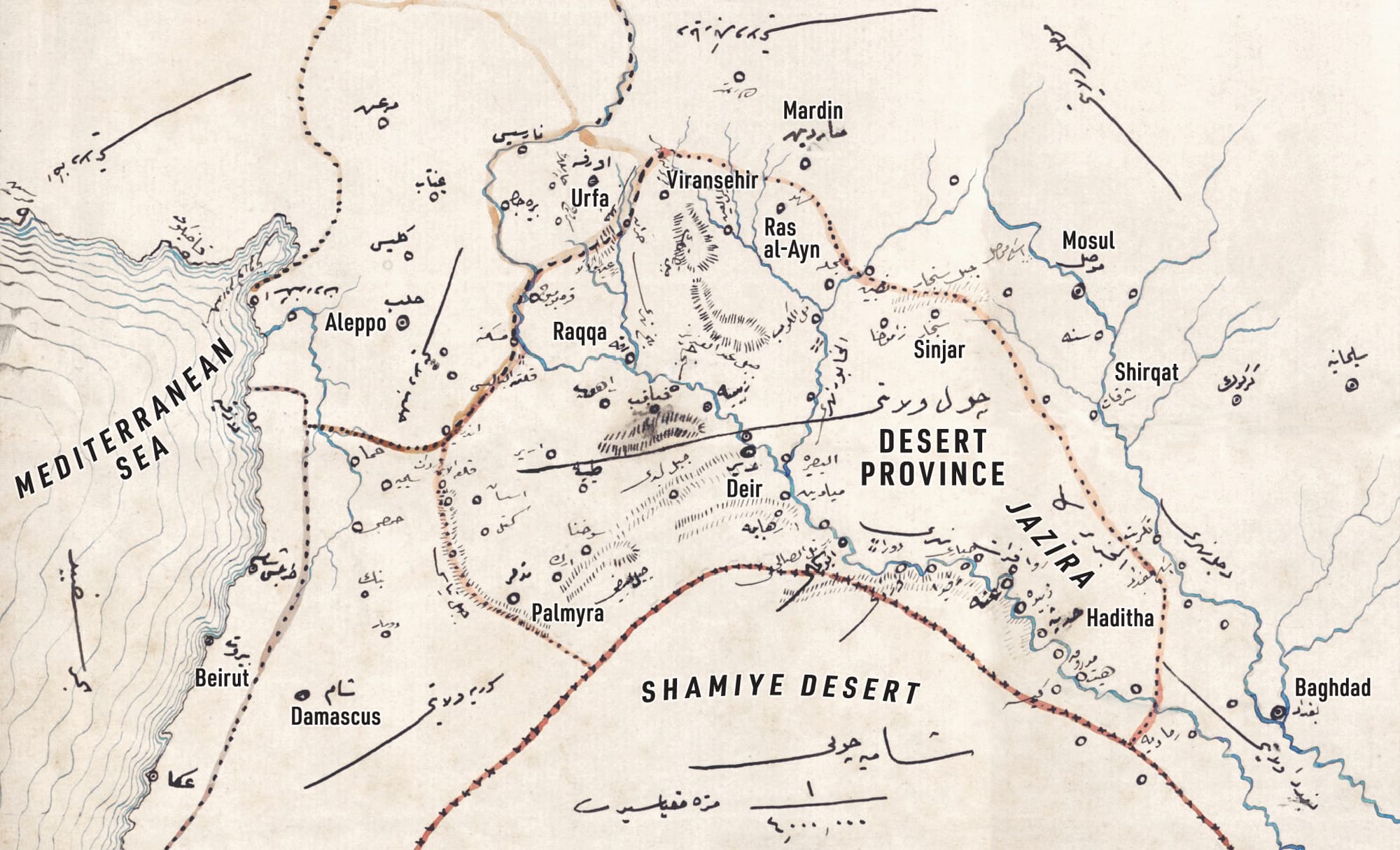

In referring to the desert and invoking the environment and borders, Erdoğan, perhaps inadvertently, was connecting the ongoing Turkish occupation of northern Syria to a much longer legacy featuring these borders. Also known as the Jazira—Arabic for “island” or “peninsula”—this arid yet fertile space stretching between the Tigris and the Euphrates at the foot of the Anatolian plateau has historically been home to mobile people in northeast Syria, southeast Turkey and northwest Iraq. Amid nomadic settlement campaigns, the Armenian genocide and post-Ottoman borders, the region was not so much a center or a periphery but both at once.

Repeated efforts to draw borders to better encapsulate the region and its desert environment—to resituate the periphery as a center, as it were—actually had the effect of establishing new peripheries and providing new openings for mobile people in the region. In this back and forth between center and periphery, the Jazira has persisted, a shadow geography haunting the broader region to this day.

The nineteenth-century Ottoman reforms known as the Tanzimat attempted to pave the path from soil to state coffers through wide-ranging changes, including a land code as well as new structures of provincial administration. These processes occurred in a period of foreign encroachment from without and nationalist agitation from within. At the same time, the empire was becoming home to hundreds of thousands of Muslim refugees of various ethnicities fleeing ethnic cleansing on its borders with the Russian Empire and in the Balkans.

In this context, the Jazira appeared as a possible solution both for expanding cultivation and settling refugees. An environment at once dry and potentially productive, it had been home to extensive cultivation in the past. All across the region, mounds known as tell—accumulations of dirt on ruins of erstwhile agricultural plenty—attested to the land’s previous use. In the time of these bygone settlements, the Jazira had been a well-known geographical unit, appearing, for example, in medieval Muslim geographies alongside more familiar toponyms like Iraq and Egypt.[2]

At the center of the effort to create Zor as a unit of governance was the perception, held by Ottoman officials, of a mismatch between the environment and the way Ottoman provinces divided it up.

By the late 1860s, the name had receded as a unit of Ottoman administration, with the space divided between provinces of Aleppo, Diyarbekir and Baghdad. Across these borders, large populations of Arabic- and Kurdish-speaking pastoralists raised sheep and camels on the region’s rich grasses and engaged in commerce with merchants in the cities on its outskirts. The Jazira, then, was a space of divided connection. It wired circuits of trade and nomadic pastoralism. At the same time, it occupied the periphery of various provinces.

How was one to manage an arid region stretching across different provincial borders inhabited largely by mobile populations? Again and again over the course of the empire’s final half century, the Ottomans attempted to manage the Jazira by drawing borders around the desert. They tried to fortify these borders through the settlement of nomads and, more fitfully, refugees. Nearly 150 years before Erdoğan linked the desert, Arabs and refugees, the Ottomans established the special administrative district of Zor, in 1871, with its capital city at Deyr on the Euphrates. The region is more commonly known today as Deir ez-Zor.

At the center of the effort to create Zor as a unit of governance was the perception, held by Ottoman officials, of a mismatch between the environment and the way Ottoman provinces divided it up. If threatened with punishment from a governor in Diyarbekir province for some infraction, nomadic pastoralists could simply slip away into Aleppo province, leaving squabbling officials in their wake. Zor would bring together both the desert and the people who moved in it, even if it did not totally encompass the broader Jazira.

Following Zor’s creation, the Shammar led a revolt against the new district. The rebellion was violently suppressed by the Ottomans. But the mismatch between political and environmental borders proved harder to resolve. Revenue collection on mobile populations was a perpetual challenge.[3] In some cases, pastoralists continued to disappear, not only across the borders of Diyarbekir province into the special administrative district of Zor, but also from cultivated regions into the desert. In other cases, it was the Ottoman officials themselves who ended up in disputes, often over which sheep should be counted for taxes in which province. One observer of these arguments between Aleppo province and the district of Zor referred to the situation as “border chaos.”[4] In the late 1870s, the administration of Zor even shifted back to that of Aleppo province, before it was once against restored as an independent administrative district in 1880.

In the eyes of one British observer, the dimensions of a district that was somehow close to Aleppo, Urfa and Sinjar (places today located in Syria, Turkey and Iraq, respectively), were nothing short of “absurd.”[5] But where some saw absurdity, many saw logic. Ottoman officials conceived of Zor as the “natural” place to rule the “midpoint of the deserts of four provinces.”[6] In one unrealized proposal to expand Zor as part of what would be called Desert province, several officials called the region “a natural governing point.”[7]

As Ottoman policies in the region shifted under Abdülhamid II, the borders, which were intended to contain the desert and seasonal migrations of nomadic pastoralists, became a flashpoint for a new set of confrontations. In 1891, the empire established mounted paramilitaries in southeast Anatolia known as Hamidiye Light Cavalry Brigades. These units ostensibly functioned as a means to co-opt Kurdish populations into state service as well as to protect against Armenian revolutionaries and Russian encroachment. In the Jazira, however, they had another task: to push south into the districts of Zor, home to branches of the Shammar confederation.

Far from wandering with no regard for borders or state officials, nomadic pastoralists knew precisely where the borders were and which administrators they could supplicate...

The foremost figure in this endeavor was Ibrahim Pasha of the Milli confederation, based in Viranşehir, located right on the border of Diyarbekir province and Zor. Sources depict Ibrahim Pasha crossing from Diyarbekir province into the district of Zor to encroach on grazing lands of the Shammar, recruit local groups to his Hamidiye Brigades and evade taxes on sheep. The situation became so dire that the district governor of Zor worried Ibrahim’s actions would cause “the destruction and disappearance of a district.”[8]

The border did not simply enclose a space. It shaped the space. Far from wandering with no regard for borders or state officials, nomadic pastoralists knew precisely where the borders were and which administrators they could supplicate and savvily used both to advance their interests. In doing so, they at once reacted to borders and, as the fears of the district governor of Zor underscored, threatened to erase peripheries altogether and transform them into something else.

Those in cities on the edge of the Jazira imagined new spatial connections across the region. In the city of Mardin, famous for its limestone buildings perched on a hill overlooking the expanses of the Jazira, notables requested their city be detached from Diyarbekir province and combined into a new province with the district of Zor as well as the Zakho district of Mosul—a territory encompassing present-day Iraq, Syria and Turkey. They did so on two grounds. First, the most commonly spoken language in the city was Arabic, as opposed to Kurdish and Ottoman Turkish in the rest of Diyarbekir province. Second, the notables claimed that their city was “the most important ruling point of the region of the Jazira.”[9] They saw their connections with the nomadic pastoralists in the “wandering grounds” to the south, near al-Hasakah, as evidence of their shared regional identity.

The proposal to remove Mardin from the “eastern provinces” and attach it to the “Arab lands,” as one official phrased it, never materialized.[10] One of the arguments formulated against the plan by the governor of Diyarbekir was that the populace of the region under Mardin’s control was in fact more Kurdish than Arab.

More than a century before Erdoğan’s call for Syrians to be sent out of Turkey and the Turkish occupation of portions of northern Syria, people were declaring connections in the opposite direction: They wanted Mardin, a city that is now part of Turkey, to be connected to the deserts to the south, part of present-day Syria. The geography of the Jazira played a central role in these deliberations, haunting the proposals of notables while never an administrative unit of its own.

In World War I, the landscape of Zor came to serve a new, more lethal purpose. No longer an object of transformation, it became an instrument of violence in its own right.

With concerns about the loyalties of Armenian citizens amid the advance of the Russian army in the east, the Ottoman state began the deportations that initiated the Armenian genocide. The borders of Zor, created over forty years earlier for the purpose of containing nomadic migration, became the destination for many of the Armenians who were systematically marched out of their hometowns all across the empire. Many were robbed, sexually assaulted and killed along the way, and those who managed to survive the gauntlet of deportation faced more violence in the deserts of Zor.

For Armenians, the borders of Zor and the bounds of the desert it encompassed became a site of massacre, disease and starvation. Yet, in a reminder of the malleable nature of the desert, the region also became a center of survival...

The wartime interior minister, Talat Pasha, did not describe the space in terms of provincial borders but rather in terms of environmental ones. As he told American ambassador Henry Morgenthau of the Armenians, “they can live in the desert but nowhere else.”[11] For Armenians, the borders of Zor and the bounds of the desert it encompassed became a site of massacre, disease and starvation. Yet, in a reminder of the malleable nature of the desert, the region also became a center of survival for some, primarily children who lived among nomadic groups in a range of roles from beloved family member to enslaved laborer.

All the while, Ottoman officials continued to discuss the question of the region’s provincial borders. In May of 1915, as the deportation regime ramped up, the infamous governor of Diyarbekir, Dr. Reşid, was asked by the Interior Ministry whether Viranşehir—now part of Turkey—ought to be considered part of Diyarbekir province or the district of Zor. Reşid neglected to answer, writing that he had “been busy with very important matters,” presumably matters connected to the large-scale massacres of Armenians in Diyarbekir province that began by late May and early June.[12]

In the waning days of World War I, the Ottoman parliament once again became consumed with questions of borders and the Jazira. As in the past, the promise of the region’s fertility made many want to redeem the space. As one deputy put it, if Cairo were rich thanks to the Nile, the Jazira could well be twice as rich given that it had two mighty rivers, the Tigris and the Euphrates.[13] A new provincial administration for the region, explicitly called “the Jazira” by parliamentary deputies, could make this dream into a reality. Others derisively commented that if one were “to consider the places in which one tribe wanders a province,” it would be laughably large, including “Basra, Baghdad, Mesopotamia, Urfa, Aleppo and Syria.”[14] Laugh though some may have, by the spring of 1918 reports discussing these regions were circulated. They revealed a clear tension between center and periphery. “For days and days,” one report noted, “the only thing visible is space and sky.”[15] Pastoralists “wandered like swarms of locusts on the edge of cultivated regions.” As if this wasn’t threatening enough, they even reportedly ate watermelons along with the rind.

The colonial dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire following World War I brought with it dilemmas and discourses familiar from the late Ottoman periphery. Maps of a Jazira state appeared during discussions at Versailles, alongside other states for Armenians, Assyrians and Kurds that never came to be. [16] The Jazira was ultimately divided once again.

Nusaybin—long located on the border between Zor and Diyarbekir province—found itself on the border between Turkey and Syria thanks to a faulty map mistakenly depicting the city north of the railway line that formed a large part of the new border in the Ankara Agreement of 1921.[17] The broader region extending from Nusaybin was also divided, no longer into separate Ottoman provinces, but rather between British Iraq, French Syria and the Republic of Turkey.

As in the Ottoman period, the movement of pastoralists across these borders allowed them to carve out some autonomy for themselves, albeit alongside newly violent forms of colonial rule brutally utilizing airpower and shrouded in the paternalistic rhetoric of the League of Nations. In the urban centers of Iraq, Syria and Turkey, far removed from the Jazira, various nationalist groups articulated their territorial claims to the region by relying on the phrase “natural borders.”[18] In a landscape where the desert had long shaped questions about borders, the environment and governance intersected once again. Or at least so it seemed.

Over the years, the Jazira continued to pop up as a territorial entity, whether as a possible French protectorate in the late 1930s or as a site for resettling Palestinian refugees in the wake of 1948.

Sometimes “natural borders” meant a call for an environmentally coherent state, but more readily the phrase referred to economic connections or even conventional wisdom: a Syria that extended from the Mediterranean all the way east to the Khabur River, for example (notably excluding large parts of the Jazira). The border schemes also largely contradicted one another—Turkey to include Aleppo, Iraq to include Diyarbekir and Zor districts—and were not implemented by the post-Ottoman colonial regimes.

Over the years, the Jazira continued to pop up as a territorial entity, whether as a possible French protectorate in the late 1930s or as a site for resettling Palestinian refugees in the wake of 1948.[19] The post-Ottoman states, however, maintained the Ottoman dynamic in which the Jazira functioned as a periphery of multiple centers, this time rooted in nation-states rather than Ottoman provinces.

Due to its continued status as periphery, the Jazira has retained a sense of integrity even as it has largely disappeared from the consciousness of those living outside of it. Building on the expansion of cultivation that occurred in the late Ottoman period along rivers and beside cities, over the twentieth century, the region transformed into an agricultural heartland—if still a political periphery—in Syria and Iraq. Connections across the region persisted because of differential customs regimes and cross-border ties of kinship, which fueled a robust smuggling trade.[20] Indeed, these commercial links were the primary reason for the placement of mines along the border between Syria and Turkey in the 1950s (Despite plans to remove them during the 2010s, many remain).

On Blaming Climate Change for the Syrian Civil War

In recent years, this geography, so often unnamed on maps, has suddenly appeared once again. In the midst of the Syrian Civil War, the autonomous region of Rojava emerged, hugging the border with Turkey in northeastern Syria. Other parts of the Jazira fell under the rule of ISIS, in 2014, as the group rapidly conquered territory from Raqqa to Mosul. Like the region itself, these developments have longer histories. Rojava is the product of the colonial denial of a Kurdish state and subsequent refugee flight south from the Republic of Turkey into Syria. ISIS, meanwhile, appeared not in an empty space—despite what breathless media accounts might have suggested. Rather, it emerged in a landscape reeling from the US destruction of Iraq, subsequent cross-border networks and the unraveling architecture of agrarian development caused by historic drought and cuts to fuel and fertilizer subsidies in Syria.

Today different portions of the Jazira—notably including the region’s oil fields—are controlled by forces of Russia, the Syrian Arab Army, Syrian Democratic Forces, Turkey, the United States and other factions. Amid this contention, as Erdoğan’s words suggest, the dream of political and environmental alignment retains its allure, with a sense that the desert of the Jazira ought to be home to Arabs rather than Kurds.

In the 2017 novel Disquiet by Zülfü Livaneli, a different kind of image of the environment and the border appears. The narrator recalls how as a child in Mardin in southeast Turkey, the dusty winds from the “deserts of Syria” would leave him struggling to breathe and “would paint all of us a red of the hot desert.”[21] A symbol of blowback, Livaneli’s image also attests to the environmental connections across borders that have been at play in various attempts to manage mobile people in the Jazira from the late Ottoman period into the present. The red dirt of the peripheral Jazira blows across borders and gets on people’s skin.

[Samuel Dolbee is Assistant Professor of History at Vanderbilt University. His book Locusts of Power will be out in 2023 with Cambridge University Press.]

Read the previous article.

Read the next article.

This article appears in MER issue 305 "Peripheries and Borderlands."

[1] “Erdoğan: Oralara en uygun olan Araplardır, çünkü çöl,” BirGün, October 25, 2019.

[2] Zayde Antrim, Routes and Realms: The Power of Place in the Early Islamic World (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), p. 97.

[3] Devlet Arşivleri Başkanlığı Osmanlı Arşivi (BOA), ŞD 2213/29, 13 Recep 1289 (September 16, 1872).

[4] BOA, ŞD 2214/20, 28 Eylül 1290 (October 10, 1874).

[5] The National Archives-United Kingdom, FO 424/123, Earl of Dufferin to Granville, July 29, 1881, Inclosure: Report by Captain Stewart on the Deir Sandjak and on Some of the Neighboring Districts, July 14, 1881.

[6] BOA, ŞD 2424/69, 3 Nisan 1296 (April 15, 1880).

[7] BOA, Y.A.RES 55/38, 25 Teşrinievvel 1306 (November 6, 1890).

[8] BOA, DH.TMIK.M 38/39, 14 Teşrinievvel 1313 (October 26, 1897).

[9] BOA, DH.İD 144/2-26, 17 Mayıs 1329 (May 30, 1913).

[10] BOA, DH.İD 144/2-26, 3 Haziran 1329 (June 16, 1913).

[11] Henry Morgenthau, Ambassador Morgenthau’s Story (Garden City: Doubleday, 1918), p. 232.

[12] BOA, DH.İ.UM 46-2/211, 27 Nisan 1331 (May 10, 1915); Uğur Ümit Üngör, The Making of Modern Turkey: Nation and State in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1950 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).

[13] Meclis-i Mebusan Zabıt Ceridesi (MMZC), İ:29, C: 1, 7 Kanunusani 1334 (January 7, 1918), p. 518.

[14] MMZC, İ:32, C: 1, 12 Kanunusani 1334 (January 12, 1918), p. 575.

[15] BOA, DH.İ.UM 10-1/2/58.

[16] Zayde Antrim, Mapping the Middle East (London: Reaktion Books, 2018), pp. 169-171.

[17] Centre des archives diplomatiques de Nantes, Syrie 298, Weygand to Poincaré, June 13, 1923.

[18] James Gelvin, Divided Loyalties: Nationalism and Mass Politics in Syria at the Close of Empire (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), p. 152; Eliezer Tauber, ‘The Struggle for Dayr al-Zur: The Determination of Borders between Syria and Iraq,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 23 (1991), p. 379; Seda Altuğ, “The Turkish-Syrian Border and Politics of Difference in Turkey and Syria (1921-1939)” in Matthieu Cimino, ed. Syria: Borders, Boundaries, and the State (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), p. 60.

[19] Jordi Tejel, Syria’s Kurds: History, Politics, and Society, trans. Emily Welle and Jane Welle (London: Routledge, 2009), pp. 29-33; Avi Shlaim, Israel and Palestine: Reappraisals, Revisions, Refutations (New York: Verso, 2009), pp. 62-64.

[20] Ramazan Aras, The Wall: The Making and Unmaking of the Turkish-Syrian Border (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020).

[21] Ömer Zülfü Livaneli, Huzursuzluk (Istanbul: Doğan Kitap, 2017), p. 18.