MERIP Reports number 94, February 1981. Cover drawing and design by Johanna Vogelsang.

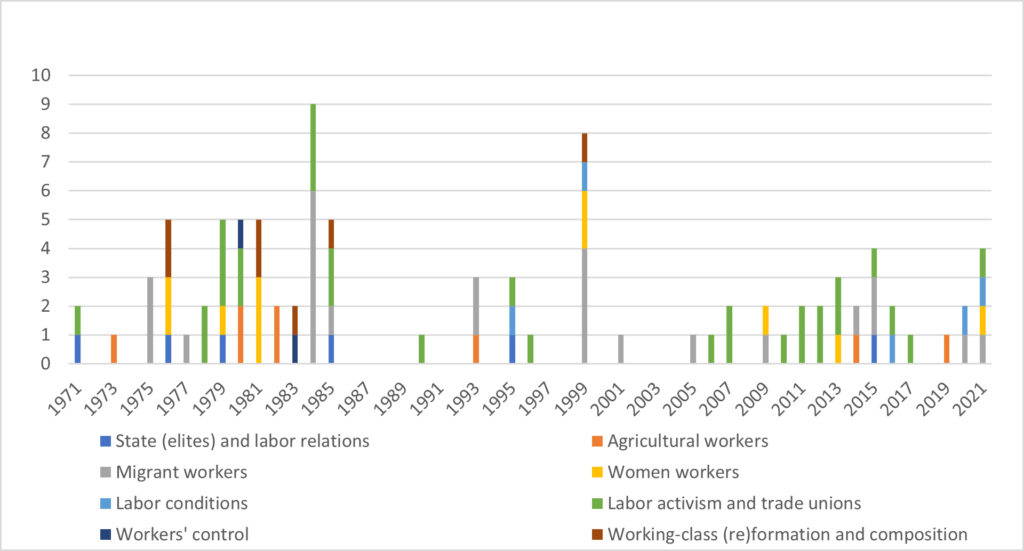

Initially MERIP Reports were short and preoccupied with Israeli colonialism, US interventions and postcolonial regimes in the region. In essays from 1972, workers were referred to in general terms to analyze the social basis of those regimes—for instance in Egypt and Iraq. But from the mid-1970s on, MERIP began to pay more attention to labor. I have counted 94 labor-related articles in the last 50 years, of which nearly half appeared between 1975 and 1985. (Figure 1) This notable era of coverage reflects both new approaches to labor in Middle East studies and the fact that 1978 was marked by an uptick in labor struggles, mainly due to the 1979 Iranian Revolution and shifts in regional and global political economy.

MERIP’s new, broad approach to labor in that period was exemplified by the attention given to migrant, women and agricultural workers. The January 1975 issue, for instance, was devoted to migrant workers from the Maghreb in France and Arab workers in Detroit and California, portending the debates on transnationalism, multiculturalism and racism that erupted in full force a decade later. Articles in this period combined a sensitivity to gender and the long-term processes of class formation, such as one that examined the position of women in the Egyptian working class and another that looked at the proletarianization of Palestinian women in Israel.

The class formation approach inspired several other articles that examine the economic, political and cultural processes through which working-class identities and struggles emerged in the Middle East. In a fascinating historical analysis published in 1976, Talal Asad explained how the British colonial state introduced capitalist relations in Mandate Palestine, alongside existing pre-capitalist relations. Asad explained how the capitalist mode became dominant as Zionist settlement increased and Palestinian land was expropriated on a massive scale starting in 1948. In the same issue, sociologist Jamil Hilal discussed the formation and restructuring of the Palestinian working class in the West Bank and Gaza Strip in the years after their occupation by Israel in 1967. In a 1981 article, Joel Beinin traced the formation of the working class in Egypt back to the industrialization initiatives of the early nineteenth century. In the same issue, Mahfoud Bennoune wrote about the origins of the Algerian proletariat.

Figure 1. Labor-related articles in MERIP (online) per year, per topic.

In 1978, contemporary labor struggles began to occupy a more prominent place in MERIP coverage. In the May 1978 issue Nigel Disney reported on the general strike in Tunisia called by the half-million strong Union Generale de Travailleurs (UGTT). At the same time, MERIP reported on and rigorously analyzed the role of workers in the Iranian Revolution. In October 1978, Fred Halliday offered a historical survey of the development of the labor movement and trade unions in Iran since the early twentieth century. The special double issue of March-April 1979, “Iran in Revolution,” published three articles on the crucial oil strikes, including a report by a strike leader, “How We Paralyzed the Shah’s Regime.” MERIP authors also took readers on to the shop floors with articles such as Mona Hammam’s survey of “Textile Workers of Shubra al-Khayma” in Egypt and Asef Bayat’s report on “Workers’ Control After the Revolution” in Iran.

The cover image on the January 1975 issue number 34 is courtesy the United Farm Workers.

In the 1980s, MERIP devoted considerable attention to workers and labor movements across the region. For example, Jean-François Clement and James Paul reported on trade unions in Morocco while Elisabeth Longuenesse wrote about the Syrian working class. In the years before the first Palestinian Intifada, Joost Hiltermann investigated the emerging trade union movement in the West Bank while ‘Abd al-Hadi Khalaf informed readers about labor movements in Bahrain.

Labor migration was an important issue, especially with the rise of oil wealth and the resulting regional inequalities. In 1984, Fred Halliday surveyed labor migration in the Arab world while in 1985 Rob Franklin addressed how migrant labor impacted politics in Bahrain. Other reports covered Yemeni, Algerian and Egyptian workers abroad. In the 1990s, MERIP continued to cover shifts in migration patterns, including the political economy of mobility of migrants, workers and refugees. MERIP more recently critically analyzed the oppressive nature of the kafala (sponsorship) system in the Gulf and in Lebanon that exploits migrant workers.

The 1990s ushered in significant transformations in state-labor relations following the decline of state-led development and the move toward infitah (open door) policies, crackdowns on labor, increasingly invasive International Monetary Fund-mandated structural adjustment programs and fire-sale privatizations. In 1995, Joe Stork reported on how Egypt’s factory privatization effort took a “violent and murderous turn” in the face of worker protests. Marsha Pripstein Posusney explained how Egypt’s new labor law removed its worker provisions and how privatization created new challenges for the left while Djavad Salehi-Isfahani addressed labor and the challenge of economic restructuring in Iran. In the wake of the Oslo Accords between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization, Graham Usher wrote about the role of Palestinian trade unions in the ongoing struggle for independence while Israeli journalist Amira Hass reported from Gaza about workers and the Palestinian authority. In a comprehensive 1999 survey, Joel Beinin retrospectively analyzed the shift from economic nationalism and populism to a nascent neoliberalism in a survey of the experience of the working class and peasantry in the Middle East.

The role of MERIP in the development of new approaches to labor in the academic field of Middle East studies is reflected in the publication of seminal works such as Hanna Batatu’s The Old Social Classes and Revolutionary Movements of Iraq (1978); Ervand Abrahamian’s Iran Between Two Revolutions (1982); Ellis Goldberg’s Tinker, Tailor and Textile Worker (1986); Joel Beinin and Zachary Lockman’s Workers on the Nile and Asef Bayat’s Workers and Revolution in Iran (1987). All these authors had published in MERIP Reports (later called Middle East Report), and most were active members of the editorial committee. They made MERIP a leading source for new types of analysis and theoretical approaches that would come to strongly influence research in Middle East studies.

Cover photo by José Luis Moreano/El País.

From the late 1980s to the mid-2000s, however, the emphasis on labor issues in Middle East Report diminished somewhat. The rise of political Islam in the 1980s and 1990s, followed by the War on Terror in the 2000s animated the public debates of this period, to which MERIP responded. Moreover, the post-structuralist and cultural turn in labor studies and the new intellectual discourse following the fall of the Stalinist regimes influenced the work of several MERIP contributors. MERIP offered innovative approaches to understanding economic change, such as Timothy Mitchell’s essays on the discourse of the development industry, neoliberalism and the tourism sector. Political economy studies of labor and the working class were also partly supplanted by alternative concerns about civil society, citizenship and the NGO-ization of political and economic governance. MERIP, however, often addressed these issues with careful attention to organized labor and workers. For example, in 1997, Christopher Alexander explored the possibilities and limitations of civil society as an antidote to authoritarianism in Tunisia noting how the regime’s crackdown on labor in the 1980s created a void that Islamists came to fill. Joe Stork’s 1993 interview with anthropologist Suad Joseph about the gendered nature of civil society highlighted the relationships between class and patriarchy.

The reporting on labor returned in the second half of the 2000s, largely with a focus on activism in reaction to the destruction wrought by neoliberal policies. Indeed, labor unions and their ability to mobilize played a prominent role in the 2011 uprisings across the region. Continuing his longstanding work on labor in Egypt, Joel Beinin covered the militancy of workers at the Misr Spinning and Weaving Company in Mahalla al-Kubra in 2007. The UGTT’s contribution to the fall of Tunisian dictator Zine El Abidine Ben Ali was highlighted in an interview with several Tunisian labor leaders and Habib Ayeb and Ray Bush trace the rural roots of uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt to inequality and marginalization across the rural sector. Beinin also surveyed Egypt’s labor movement in the wake of the 2011 overthrow of Husni Mubarak and their role in the movement against the Islamist president Muhammad Mursi. In 2012 Fida Adeley discussed the emergence of a new labor movement in Jordan, although the country was less affected by the 2011 revolutionary wave.

In recent years, Middle East Report has continued its coverage of workers and labor issues in the region. Its writers have reported on labor organizing in Iran, the struggle of Palestinian workers in Israel and those seeking social justice under the Palestinian authority, as well as migrant workers facing COVID-19 lockdowns in the Gulf and exploitation by the private contractors that sustain the US military in Iraq and Afghanistan. There are also new issues to cover, such as the expansion of the service sector as well as the large size of the informal sector and the precarious labor conditions and obstacles to collective organization that these create. Meanwhile, high unemployment, particularly among youth, is likely to have long-term political consequences for states across the region while workers, more so than the capitalist and middle classes, have the potential to play an important role in struggles for democratization. Despite possible gaps, MERIP has made a lasting contribution to a more nuanced understanding of the Middle East by highlighting the role of labor in its wider social, political and economic transformations. Most significantly, MERIP has contributed to creating a better understanding of global changes and common struggles for social justice by revealing how workers in the Middle East are connected to workers in other parts of the world through migration, neoliberal reforms and anti-labor politics.

[Peyman Jafari is a postdoctoral research associate at Princeton University’s Sharmin and Bijan Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Iran and Persian Gulf Studies.]