Joe Stork is one of the founders of MERIP and served as the editor of Middle East Report until 1995. He went on to be deputy director of Human Rights Watch’s Middle East and North Africa division. Chris Toensing was executive director of MERIP and editor of Middle East Report from 2000 to 2017 and since 2018 is a senior editor at the International Crisis Group. They were interviewed by Lisa Hajjar, professor of sociology at the University of California, Santa Barbara and MERIP editorial committee member, in September 2021.

Lisa Hajjar: The media landscape has changed profoundly over the 50 years since MERIP was created. How would you explain its longevity when so many other outlets have come and gone?

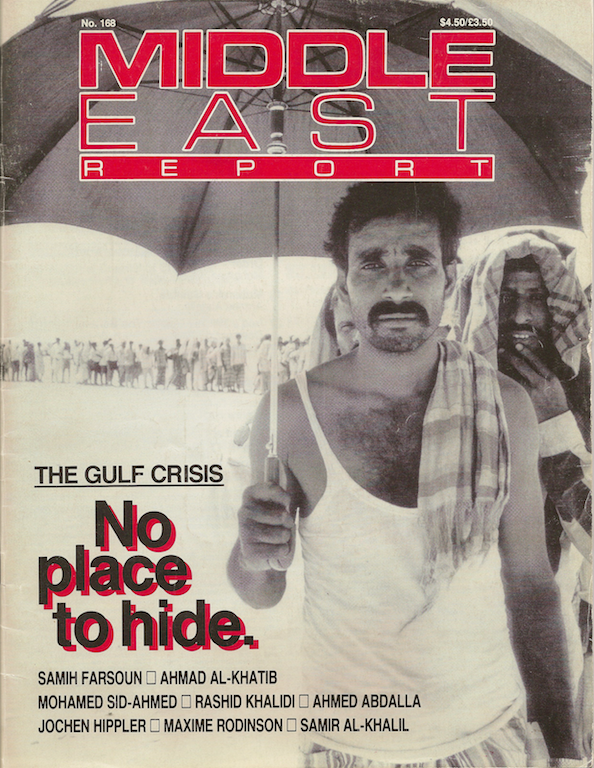

Middle East Report no. 168, January-February 1991. Cover photo by Chris Carrter, design by Kamal Boullata.

Joe Stork: The big change is, first of all, the emergence of electronic media and then social media. As far as I can see, MERIP hasn’t played a huge role in social media, but it has adapted, obviously, since it’s now an online publication. But to address the other part of the question about the many other outlets that have come and gone: Many publications that existed when we started are still around. What’s gone is a certain brand of activist left media. I have to qualify that, because you have a different kind of left media today. You have phenomena like Jacobin, for instance, which is really serious and impressive and has high production values. That’s very different from the so-called underground press that was around in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Those guys have come and gone. The Nation, for example, and Middle East Journal are still here. I would say we have helped change them. I think there’s a certain level of openness to a range of views, especially on Israel and Palestine and issues relating to the US presence in the region that wasn’t there in the 1970s.

Lisa: Can you say more about how the work of MERIP and the content of Middle East Report (MER) influenced the way other media report on Middle East-related issues?

Joe: It’s not just what MER did that was influential, it’s what the people who made up MERIP did. People like you and all the other editors, the core editors, who were on the editorial committee year after year. It’s what our folks were doing in academia, the books they produced and so forth. It wasn’t just MERIP, it was the community. It’s no longer run as a collective like it was when we started, but it’s a cohort of sorts. MERIP editors have been presidents of the Middle East Studies Association (MESA), for example.

At the same time, something I’ve been saying since the 1980s is that there’s been a sidelining of expertise, of real expertise. Journals and the media that are producing work on the Middle East are, as a general rule, better, but the expertise of those people has been sidelined. I can remember in the 1970s you had not particularly high-profile academics who would be invited onto the talk shows because they were Middle East experts. When was the last time you saw somebody like that on any of these major talk shows? I don’t watch a lot of talk shows, so maybe I’m not entitled to this opinion.

Lisa: Chris, you were an editor at a different period, when this rise of electronic media and social media came about.

Chris Toensing: It started before I came on. Our first website was built in 1996 and we were already doing online pieces. Things really took off in late 2000, with the second Intifada, and then even more so with the 9/11 attacks.

I agree with everything that Joe said about the media landscape. You could start by asking: What was MERIP’s original intent? It was to be a progressive voice on the Middle East in the existing left media in the United States. And what has certainly happened in the intervening years is that whereas a publication like The Nation was once kind of hostile to MERIP’s point of view about, say, Palestine, that’s no longer the case at all. The other thing is the rise of the new left media that Joe referenced, such as Jacobin. The generation of leftists that runs these publications is completely with us politically on Palestine, the critique of US imperialism in the Middle East and the critique of Saudi Arabia and other authoritarian states allied with the United States. All those critiques for which MERIP was once a standard bearer are now mainstream in the US progressive left. I think we can take some modest credit for that. That change has taken away some of the specialness of MERIP, but of course it’s a salutary change in all other ways.

Still another thing is that the mainstream or corporate media has become a little bit more permeable. It’s weird, though: You also have the phenomenon that Joe referred to, which is the revolving door between the think tanks, government and corporate journalism. For instance, you have George Stephanopoulos, who was Bill Clinton’s communications director, hosting a major Sunday morning talk show on ABC, or Nicole Wallace becoming an MSNBC host after having been communications director for George W. Bush. This ecosystem that has developed in Washington is its own little bubble. It’s not totally ideologically coherent, but it doesn’t include people like us. It’s still a cohort that is firm in its commitment to a certain hegemonic role for the United States in the world. As we’ve said many times in MERIP’s pages, there’s more continuity between neoconservatism and liberal internationalism than there is between the liberals and any genuine left critique of US policy. Lastly, there’s what’s happened in Middle East studies, which is that MERIP’s perspectives have become totally mainstream.

Lisa: I would put it slightly differently. I’d say that people—scholars—of younger generations have really gravitated to these critical perspectives.

Chris: Yes. And it’s also generational in another sense. We now have two generations—the younger millennials and Generation Z—who have grown up entirely in a world in which the United States has been at war overseas. They’ve seen not one, but two candidates get the presidency without winning the popular vote. They’ve seen a succession of total fiascos, whether it be the Iraq war or Hurricane Katrina or the financial meltdown of 2008 and on and on with not only no real accountability for those in charge but also no real questioning of the underlying principles. What right does the United States have to launch overseas invasions, for instance? Gone are the days when Americans could expect to be better off materially than their parents. These new generations are facing possibly disastrous material realities, not to mention the climate crisis, that are just different from what my generation or those preceding mine faced. The contradictions of capitalism have become sharper and harder to deny.

Lisa: Let’s go inside the MERIP community. One of the unique or admirable aspects of Middle East Report is the ability to accommodate both scholarly and activist perspectives. As longtime editors, how have the two of you navigated that balance, both in terms of soliciting pieces and also managing various configurations of the editorial committee?

Joe: When MERIP started—and I’m talking about, say, the first three or four or five years—expertise was not our profile or strength. I mean, to be honest, it was enthusiasm and activism. Our pieces were well researched in a certain way, but we brought a left perspective; the expertise came later, by the end of the first decade. That’s when we began bringing in the scholars who were genuine and politically engaged experts, for example those with expert knowledge of Iran like Ervand Abrahamian or Fred Halliday. And then you had people like Joel Beinin and Zach Lockman who brought expertise, not just a left perspective, on Israel/Palestine. I think that was a gradual shift. When I was still at the helm, it became more of a balancing act to prevent us from prioritizing scholarly expertise over the activist left perspective that was our original mandate.

But looking at the magazine as it developed over the decades, you didn’t have—for many periods of those five decades—the same kind of activism, the sensibility, the political perspectives that have been out there at various times in the past. When there weren’t people in the streets protesting for one reason or another, the people writing for and reading MER were academics talking to academics. I think that was a problem or maybe continues to be a problem.

Chris: I broadly agree. As far as connecting with the activist world, let me tell a story. The first time I ever met Joel Beinin was shortly after I took the job, sometime in the spring of 2000. It would have been shortly after the big anti-globalization protest in Seattle that really put the global justice movement on the map. I remember that he and I agreed that this was the most vital sector of the left in North America and that we at MERIP had to find a way to connect to it somehow. So, we tried to do that. On the morning of September 11, 2001, before I heard the news of what had occurred in New York, I was editing a piece about the World Trade Organization and the Middle East, as we were planning a substantive primer on this set of issues. All of that work, which would have been a way of relating to this movement and a way of trying to reconnect MERIP to its activist roots, went up in smoke on 9/11 and all that came after. The project never saw the light of day.

-768x1001.jpg)

Middle East Report no. 239, Summer 2006. Cover photo by Jason Eskenazi, design by Geoff Hartman.

For the next decade or more, we were not completely but largely consumed with issues of war and peace. This focus temporarily boosted our readership and attracted some foundation support, though the support rapidly went away as soon as the Iraq war was launched. And the readers started to peel off, too, as the decade went on. I’m partly getting back to the first question. It was clear in my mind that MERIP should be trying to cover the momentous changes in the region happening as a result of the US War on Terror, and then the Iraq war and the related actions that various states in the region, such as Israel, Turkey and others, were taking to exploit that environment. But because the United States itself was so embroiled in all this stuff, the mainstream media was flooding the zone with reporters as well. So, you have this explosion of coverage in the mainstream media of the same stuff that we were trying to cover. And some of it was really good, like the reporting of Anthony Shadid. So, again, paradoxically, at the very time when we should have been well positioned to help our readers understand what was going on, there were the limitations of being a quarterly print magazine and our perennial financial difficulties. The fact that we couldn’t pay very many authors really inhibited us from being able to cover developments as they were happening. I tried really hard with MER Online articles to provide timely news analysis. But I’m not sure we could have done too much more, given the obstacles.

The other thing I would say is that I definitely took the editor’s job with the vision of making the writing more accessible. I wanted to publish more journalists. I wanted the choice of topics to be less driven by academic debates—what was hot theoretically—and more by what was topical and urgent. I’m not going to lie. I encountered a lot of resistance to that. And the fact is, we drew almost entirely upon academics as authors and as editors. I gradually swung around to the view that what we should do, given our reality, was to look at the university classroom as an activist space and produce material that was accessible at that level so that the people who were our primary base as both authors and readers could have stuff that was useful to them in their primary role as teachers. That’s a different vision from what MERIP originally had or what I originally had as an editor, but I think it was a more realistic vision for what MERIP can achieve consistently.

That said, I think MERIP can still publish stuff that reaches many other and different kinds of people. The last time I was aware of the subscription list, we had plenty of people in the US military and the diplomatic corps from various countries. And anecdotally, over the years I ran into more than one person deep in the belly of the beast who was well aware of MERIP and even agreed with some of the stuff we published.

Also, in part to get back to MERIP’s original public education mission and in part to solicit foundation support, we made an effort to broaden the scope of our work beyond publishing Middle East Report, starting in the late 1990s. One project to create a high school-level curriculum unit about Israel-Palestine sadly did not see the light of day. The media outreach program had more success. It went through several iterations, beginning with “press information notes,” short backgrounders on breaking stories that we hoped mainstream media reporters would use for their stories. Those pieces later morphed into MER Online. The second iteration basically consisted of efforts to place op-eds in mainstream media, which saw us get a byline (as far as I know, our first) in The New York Times (Ian Urbina’s piece with Bishop Desmond Tutu about the Israeli occupation). Later we added more systematic outreach to print and broadcast media, first in the form of “push quotes” or brief analytical comments on breaking news from MER editors and authors along with their contact information for further comment.

The last and most sophisticated iteration was Middle East Desk, largely conceived by editor Shiva Balaghi, who was then at NYU. Shiva was crucial in winning a two-year grant to build an interactive website consisting of a map of the region with country pages containing basic facts as well as a “datebook” of current or upcoming newsworthy events and names of country experts whom journalists could contact for comment. The grant wasn’t renewed, unfortunately. None of this work made MERIP a household name, exactly, but it did get our perspectives a much wider airing than they would otherwise have had.

And, although we were never simply part of the Middle East studies world, we were part of it, and it was a large part of our profile and appeal. I come from academia myself and my concerns were often academically inclined as well.

Joe: Some of us might have wanted to be academics. It wasn’t an antagonistic relationship. Some of us were activists who decided not to pursue academia, but really liked that kind of work and research and writing.

Chris: And we supplied a platform for academics who really wanted to be part of the activist game and to have a bigger impact with their research.

Lisa: The activism of the early years that Joe was describing shifted over time. That brand of “Third World solidarity activism” was a thing in the seventies. But to the extent that you can see it in the growing pro-Palestinian movement since the first Intifada or the anti-globalization movement, I would give MERIP credit for being able to continue producing useful information for those activists and writing about those political changes. I also think the organization pivoted to more quickly put out timely, topical writings. But getting more professional journalists to write? Journalists need to get paid, and academics write for free. Which brings me to an important point. MERIP has always relied on volunteer labor, especially the volunteer labor of people who have served as members of the editorial committee. Can you reflect on the role of the ed com over time and the challenges or privileges or benefits of that kind of volunteer labor and collective structure, while acknowledging that it’s increasingly drawn from the academy?

Joe: As I think about who was sitting around the table in, say, the early 1980s, very few of the people were not academics in some way, whether grad students or folks with teaching positions or professional researchers. And that wasn’t a bad thing because they were people interested in talking about the realities in Iran or in Israel or whatever. I have been pulling together stuff in my basement for the potential MERIP archives, and I found a bunch of cassette tape recordings of the editorial committee sitting around the table and discussing what was going on and the kind of issues that we should be dealing with. The other point to make is who we brought in. Rashid Khalidi, although he wasn’t a member of the ed com, was one of the people who was from the region, who brought a richness to those conversations. I think of people like Selim Nasr and Salim Tamari, for instance, and there are many others who infused the conversations with voices from the region.

But I think that points to another thing you wanted to discuss: our low points at MERIP. For me, the low point was always our inability to attract the kind of financial support that we needed to make a real go of it, frankly. All the volunteering to write the articles and to some extent to edit the articles and so forth. All of that extremely important labor is what enabled MERIP to survive. But we deserved a lot more support than we got, and we never got enough that we could take a deep breath. We got very, very depressed about that lack of responsiveness from either the philanthropic community or potential big donors. We never got the kind of recognition that would resolve our financial worries. It’s still a big part of the problem today.

Chris: I agree. Without the editorial committee in particular, MERIP could not have continued to exist. It would have been totally unsustainable. The editors are the unsung heroes of MERIP.

Joe: Can you imagine what it could have been like if we had a financial base that would enable us to pay contributors?

Chris: Now that I work for a nonprofit that is comparatively well-heeled, I have a different appreciation for the fact that MERIP, over the years, has actually done a remarkable amount of work for an organization that was not only always scrambling to get the work done, but scrambling to keep the lights on. Joe knows this better than anyone. For me, it was an ambient stress and eventually, as staffing shrunk because of our financial difficulties, it became unsustainable for one person to do what was previously two or three jobs—executive director and editor plus the administrative office work.

Lisa: Financial woes and hardships are your mutual low points. What are some of the high points of your involvement with MERIP?

Joe: We always have had some dynamite people on staff and as interns who have gone on to do great things. Despite all the financial troubles, I was always invigorated by the quality of the staff I worked with, like Jim Paul, Martha Wenger, Peggy Hutchison and Esther Merves. And there are people who started with MERIP as interns—like you, Lisa—when they were students who have developed big academic careers. There is Michelle Woodward, who started young and still remains as, perhaps, the living link between the past and the present of MERIP staff.

-768x1001.jpg)

Middle East Report no. 262, Spring 2012. Cover photo by Thomas Hartwell, design by Jimmy Bishara.

Chris: My best memories are of working with various people in the office over the years. Otherwise, the high point was February 11, 2011, when we happened to be holding an editorial meeting at NYU on the day that Mubarak was deposed. We were doing a panel discussion in advance of the next day’s editorial meeting. I think I was supposed to speak about Iraq. We just decided to completely shift gears, and we all talked about Egypt. Everybody was overjoyed by the turn of events. Then that evening, Zach was playing host at dinner. I remember very clearly, Zach raised a glass to us all and said something along the lines of: “I’m so glad that I’m with my MERIP comrades tonight, when this is happening.” And the next day we had a fabulous, productive editorial meeting. It was alchemic. I can look at the editorial that we produced afterward and almost remember who made each point that we integrated into it.

Joe: I don’t know that I have a singular high point like that. My high points were those meetings where we were sitting around a table having really terrific discussions that would shape issues of the magazine. It was the intellectual energy and political energy and the comradeship of the editorial committee and in that larger sense, the people we brought in as contributing editors. Even after the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982, which was an awful and depressing time, there was a sense that we had work to do and there are people who wanted to hear from us. I would pose the question of whether that continues to be true. Is there a future to this MERIP project? Is there a cohort of people out there who want to hear from MERIP?

Lisa: That’s a very nice segue into the last question. As people who have been foundational to MERIP in different periods, although you both are now outside but still engaged, how do you see or hope the future might look?

Chris: One of the hard lessons I learned in my time is that by dint of what it is and the structural limitations that we’ve been talking about, MERIP was always going to be a niche publication. I always thought the niche could be bigger, but I’m not sure of that anymore. I think the niche has gotten smaller due to the explosion of other outlets that do things very similar to what MERIP is trying to do and due to some of the other changes that we’ve already talked about. I think it’s a real question whether MERIP still has a unique perspective. That is what made MERIP its bones—its perspective, not expertise, and the political clarity and the political culture of the organization. Is that unique anymore? I don’t know. I think that when we’re asking the existential question, we focus entirely on whether the organization is financially sustainable. The real existential question is what is the project? What are we trying to do? And is there a demand for that mission in the world? I think that’s a hard question for us to ask ourselves.

Lisa: It’s a perennial question. We’ve been asking ourselves that for decades.

Joe: I don’t know if it’s the perennial question because I think there were many, many years when it was not a question.

Lisa: I mean, it has been a perennial question since the early 1990s. For me, the camaraderie is a living legend, now that I’m pulling what is probably my fourth stint on the ed com. These reflections that you two have offered and the important questions you have raised about the present and the future are a meaningful way to commemorate 50 years of MERIP.