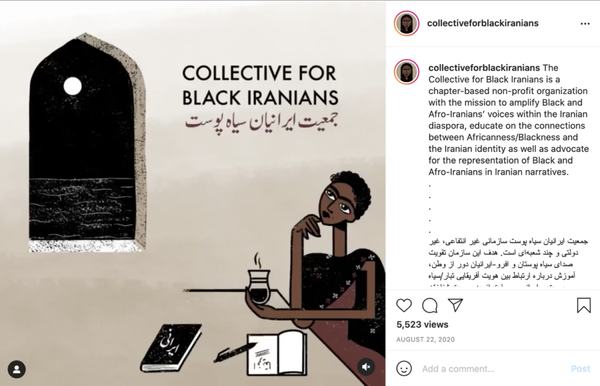

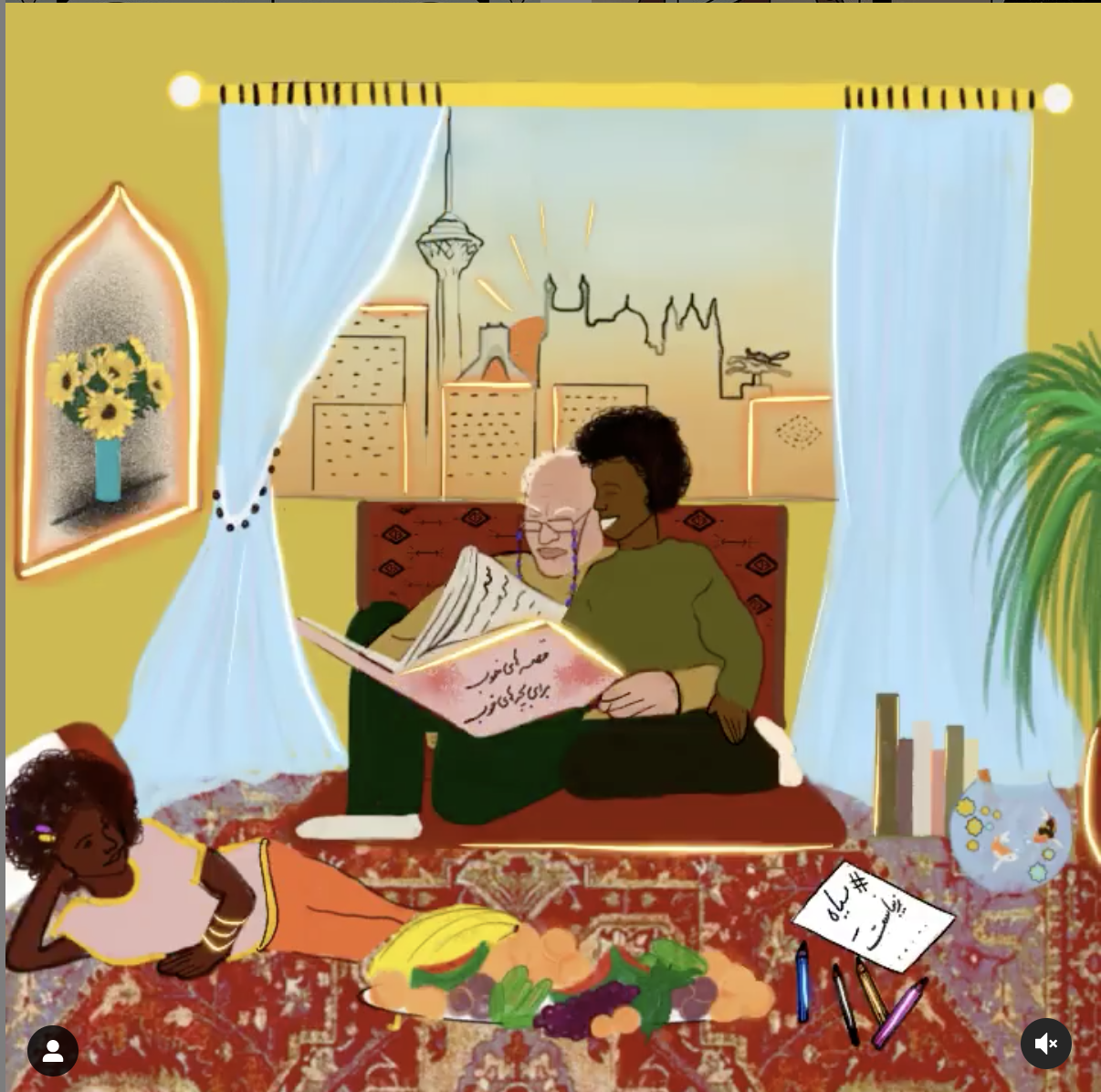

Writing Ourselves into Existence with the Collective for Black Iranians

The groundbreaking work of the Collective for Black Iranians is the first and only effort of its kind in Iran that brings together the voices of Black and Afro-Iranians, sharing their stories and experiences to foster greater racial consciousness and combat the anti-Black racism endemic to the Irani