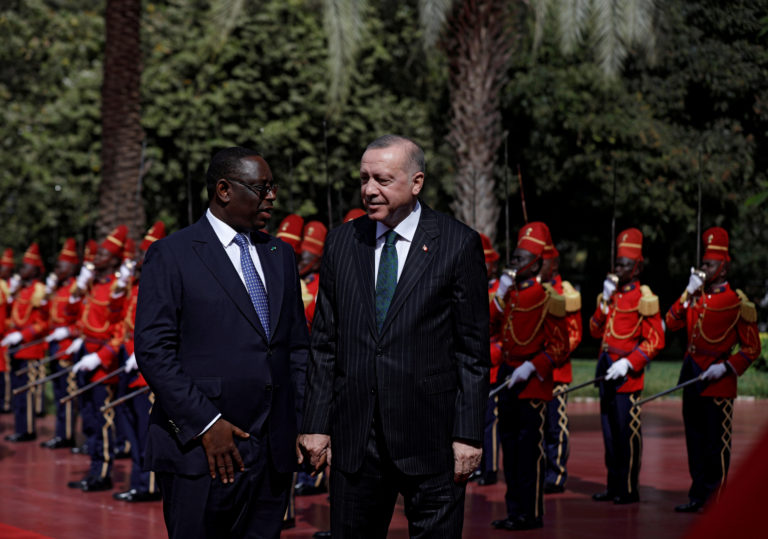

Senegal’s president Macky Sall welcomes Turkey’s counterpart Recep Tayyip Erdoğan at the presidential palace in Dakar, Senegal, January 2020. Zohra Bensemra/Reuters

The White Turk label initially referred to the bureaucratic elite who were stereotypically Istanbul-born, blonde and francophone and was meant to be a critique of their elitism.[1] At that time the White Turk signified those who were reluctant to share the state power with non-white others coming from a provincial background. Over the years, the boundaries of the White Turk category have been expanded, refined, contested and redefined.[2]

Yet the Western orientation of White Turkishness remained a constant until recently. Metaphorical whiteness was, after all, a legacy of 1930s race science, sponsored by the state as a way to prove the whiteness of the Turkish race and hence its membership in Western civilization.[3] In a similar spirit, claiming whiteness in the wake of September 11, 2001 meant cutting ties with the Islamic East, now associated with terrorism, and belonging to the civilized West.[4] While the connections between light complexion, state power and Westernization suggested by the White Turk identity remain strong to this day, these connections alone do not account for the changing meanings of whiteness. There are, rather, competing meanings of whiteness in contemporary Turkey that reflect struggles over state power.

Today, the populist authoritarianism of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) led by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan rests on a racialized moral regime in which the people, frequently referred to as Black Turks, are positioned against the elite, represented as the White Turk. Simultaneous with the mobilization of this anti-elitist discourse, however, a new investment in whiteness by the ruling classes has emerged, specifically through contact with Africa south of the Sahara. In other words, while whiteness as a metaphor of privilege is projected onto the opponents of the AKP in Turkey, the representatives and supporters of the AKP identify with phenotypical whiteness in the racial terrain of Africa. This racial claim does not, furthermore, indicate an orientation toward the West. Instead, Turkish whiteness is constructed in this context as the civilizational antithesis of the West. As such, it supports arguments about Turkish exceptionalism and the redemption of whiteness in postcolonial Africa. In order to understand this complex matrix of metaphorical and phenotypical whiteness, it is first necessary to unpack the construction of Black Turkishness within Turkey. Appropriation of Blackness as a symbol of oppression in Turkish politics not only undergirds populist polarization today, but at the same time hijacks the actual experiences of racial oppression among Blacks living in Turkey, mainly Afro-Turks and African immigrants.

Black Turk Versus White Turk

Building on and further politicizing the White Turk category, the leaders of the Islamist politics began to define themselves and their constituents as Black (zenci) Turks in the late 1990s.[5] This new terminology was an explicit reference to the American racial categories suggesting an analogical similarity between the oppression of African Americans by the white supremacist system and that of pious Muslims by the secularist regime in Turkey.[6] Recai Kutan, the leader of the Virtue Party, made a comparison between the Jim Crow laws and Turkish secularism when he said, “Like the blacks’ enrollment in the whites’ schools in America, our veiled daughters will soon be able to enroll in universities.”[7] Kutan’s prediction proved correct after the AKP, founded by a younger generation within the Islamist movement, came to power in 2002. Even so, neither the allure of analogy with American racism nor the political uses of metaphoric whiteness and Blackness have ceased in the AKP’s Turkey. Rather, the White Turk versus Black Turk dichotomy constitutes the core of the AKP’s nativist populism.[8]

The Whitening of the Black Turk in Africa

While the AKP continues to mobilize metaphorical Blackness to sustain the argument that it represents the true will of the people against the White Turk elite, whiteness acquires a whole new set of meanings in Africa south of the Sahara. In the last two decades, the African continent has gradually become the laboratory for the AKP’s new foreign policy, characterized by a diplomatic activism in the Global South, incorporation of non-state actors such as business communities and civil society organizations into the diplomatic process, humanitarian intervention and a business-oriented agenda.[12] Based on peacebuilding, official development assistance and Islamic charity and humanitarianism, Turkey has, on the one hand, claimed the status of a “humanitarian state” in the continent.[13] On the other hand, the state has facilitated the creation of African markets for Turkish exporters, investors and construction companies through economic forums, business delegations and free trade agreements. This state-orchestrated mobilization for developing diplomatic, economic, humanitarian and religious relations with Africa south of the Sahara has, furthermore, set the stage for the redefinition of and new investment in whiteness.

The Minister of Foreign Affairs at the time, Ahmet Davutoğlu was also present at the 2010 diplomatic visit to Cameroon. Three years later, he elaborated on the moral claims of this newly discovered whiteness at the African Strategies Sectoral Evaluation Meeting in Ankara: “The African needs today more than anything else attention, care, and compassion based on a relation between equals. That’s why a friend of mine, an African Minister of Foreign Affairs said, ‘As Turks, you are our brothers with different skin color.’ Whereas skin color difference used to evoke [memories of] colonization and more negative connotations, now they [Africans] too have embarked on a new discovery with Turkey.” According to Davutoğlu, Turkish exceptionalism in postcolonial Africa is defined by the humanitarian core of its Africa Strategy. In this racialized geopolitical imagination, what makes Turkish whiteness radically different from European whiteness is its moral essence that is manifested as “attention, care and compassion” toward Africans. Paradoxically, Davutoğlu’s bifurcation of whiteness into colonizer and non-colonizer-caregiver in fact builds on the racist tropes of European colonialism with its paternalistic tone, equation of goodness with whiteness and the infantilization of Africans.

Interpellation into the category of white by African interlocutors plays a fundamental role in the new investment in whiteness in Turkey. In other words, the racial rebirth of the Black Turk as white-of-a-different-order is mediated through the revoicing of Africans—the process by which the other’s words are appropriated, reinterpreted with new meaning and assimilated into the speaker’s intentions.[15] Another process of revoicing similar to that of the Cameroonian Minister can be traced in the column entitled “Turkey: A Different White Man” published in a pro-government Turkish newspaper.[16] The columnist who accompanied Erdoğan on his presidential visit to Guinea in 2016, recounts a Guinean public employee asking him “Are you sure you are a white man?” When the journalist asks why he posed the question, the man allegedly answers: “The white man comes, shoots, takes and goes. You come and you not only help, but you also stroke our hair (saçımızı okşuyorsunuz). If you ask me, you cannot be a white man. You must be a Black man who is whitened (rengi ağarmış).” The disbelief claimed to be expressed by the Guinean interlocutor is a recurrent theme in the construction of Turkish exceptionalism in postcolonial Africa. It highlights the Turk’s racial sameness with—yet civilizational and moral difference from—the white European.

Once again, it is the moral essence described by Davutoğlu that extends from the provision of aid to the act of stroking the African’s hair that makes Turkish whiteness radically different from European whiteness, according to the journalist’s column. This paternalistic corporeal practice suggests, however, a continuity with colonial whiteness and not, as the columnist imagines, a civilizational antidote to the violence it has unleashed. The journalist’s revoicing of the Guinean interlocutor as saying, “You must be a Black man!” furthermore harkens back to the appropriation of Blackness by the leaders of the Islamist movement since the 1990s in Turkey. But more than a symbol of oppression and subordination, Blackness here operates as a moral passport to intervene in Africa. Interpellated as white, yet reportedly perceived as Black by Africans, the Turkish ruling classes claim moral legitimacy while at the same gaining access to the privileges of whiteness in postcolonial Africa.

Whiteness has acquired new meanings in Turkey through transnational processes of racialization in Africa south of the Sahara. Historically associated with Western civilization, whiteness continues, on the one hand, to symbolize power and privilege in the AKP’s racialized moral regime. In populist discourses, the White Turk denotes an elusive category of Westernized elite positioned against the true people whose authenticity and subordination is marked by metaphorical Blackness. On the other hand, the new investment in phenotypical whiteness in Africa south of the Sahara has redefined Turkish whiteness. From an indicator of membership in Western civilization, whiteness has recently come to indicate an alternative civilizational project in the racial terrain of Africa. Navigating a complex symbolic order of sameness and difference vis-à-vis the West, the Turkish ruling classes have reclaimed whiteness to carve out for themselves a legitimate position in the continent. Whiteness licenses the Turkish political and economic elite to present themselves as bearers of modernity, technology and development. Claiming a different kind of whiteness that is defined by a humanitarian core as opposed to a colonial one, furthermore, situates Turkey as racially equal and morally superior to the West. The paradox of this civilizational project, however, resides in the false contrast between humanitarianism and colonialism whose racial logics overlap. Aspirations to redeem whiteness through Turkish exceptionalism in Africa south of the Sahara, therefore, reinforce rather than undermine global white supremacy.

[Ezgi Güner is a lecturer in the Department of Sociology at Boğaziçi University, Istanbul.]

Endnotes

[1] Ufuk Güldemir, Texas-Malatya (Istanbul: Tekin Yayınevi, 1992).

[2] Sedef Arat-Koç, “(Some) Turkish Transnationalism(s) in an Age of Capitalist Globalization and Empire: ’White Turk’ Discourse, the New Geopolitics, and Implications for Feminist Transnationalism,” Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies 3/1(Winter 2007); Tanıl Bora, “Notes on the White Turks Debate,” in Riva Kastoryano ed. Turkey between Nationalism and Globalization (New York: Routledge, 2013); Christoph Ramm, “Beyond ‘Black Turks’ and ‘White Turks’–The Turkish Elites’ Ongoing Mission to Civilize a Colourful Society,” Asiatische Studien—Études Asiatiques 70/4 (2016); Seda Demiralp, “White Turks, Black Turks? Faultlines beyond Islamism versus Secularism,” Third World Quarterly 33/3 (2012).

[3] Murat Ergin, Is the Turk a White Man? Race and Modernity in the Making of Turkish Identity (Leiden: Brill, 2017).

[4] Ilgin Yorukoglu, “Whiteness as an Act of Belonging: White Turks Phenomenon in the Post 9/11 World,” Glocalism: Journal of Culture, Politics and Innovation 2 (2017).

[5] In all the examples I use in this paper, I translate zenci as Black which can also be translated as negro.

[6] Demir Demiröz and Ahmet Öncü, “Türkiye’de Piyasa Toplumunun Oluşumunda Hegemonyanın Rolü: Bir Gerçeklik Projesi Olarak Beyaz Türklük,” in Ahmet Öncü and Orhan Tekelioğlu eds. Şerif Mardin’e Armağan (Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2005).

[7] Milliyet, “FP’den zenci benzetmesi,” September 20, 1998.

[8] Sedef Arat-Koç, “Culturalizing Politics, Hyper-Politicizing ‘Culture:’ ‘White’ vs. ‘Black Turks’ and the Making of Authoritarian Populism in Turkey,” Dialectical Anthropology 42/4 (2018).

[9] Deborah Sontag, “The Erdogan Experiment”, The New York Times, May 11, 2003. For a linguistic discussion of this statement see Alev Bulut, “Translating Political Metaphors: Conflict Potential of zenci [negro] in Turkish-English,” Meta 57/4 (2012).

[10] For a critical discussion of this statement see Michael Ferguson, “White Turks, Black Turks and Negroes: The Politics of Polarization” in Umut Özkırımlı ed. The Making of a Protest Movement in Turkey: #occupygezi (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

[11] “Ince: Erdoğan is a White Turk, I am the Black of Turkey,” Cumhuriyet, June 10, 2018. [Turkish]

[12] Federico Donelli, Turkey in Africa: Turkey’s Strategic Involvement in Sub-Saharan Africa (London: I.B. Tauris, 2021); Elem Eyrice Tepeciklioğlu and Ali Onur Tepeciklioğlu, eds. Turkey in Africa: A New Emerging Power? (New York: Routledge, 2021).

[13] Pınar Akpınar, “Turkey’s Peacebuilding in Somalia: The Limits of Humanitarian Diplomacy,” Turkish Studies 14/4 (2013); Fuat Keyman and Onur Sazak, “Turkey as a Humanitarian State,” POMEAS Policy Paper 2 (2014); Yunus Turhan and Şerif Onur Bahçecik, “The Agency of Faith-Based NGOs in Turkish Humanitarian Aid Policy and Practice,” Turkish Studies 22/1 (2021); Pınar Akpınar, “Turkey’s ‘Novel’ Enterprising and Humanitarian Foreign Policy and Africa” in Joost Jongerden ed. The Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Turkey (New York: Routledge (2021).

[14] “Cameroonian Minister to Gul: ‘You’re White, But You’re One of Us,” Milliyet, September 22, 2010. [Turkish]

[15] Mikhail M. Bakhtin, The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2011)

[16] Şeref Oğuz, “Turkey: A Different White Man,” Sabah, January 11, 2018. [Turkish]