Remembering Slavery at the Bin Jelmood House in Qatar

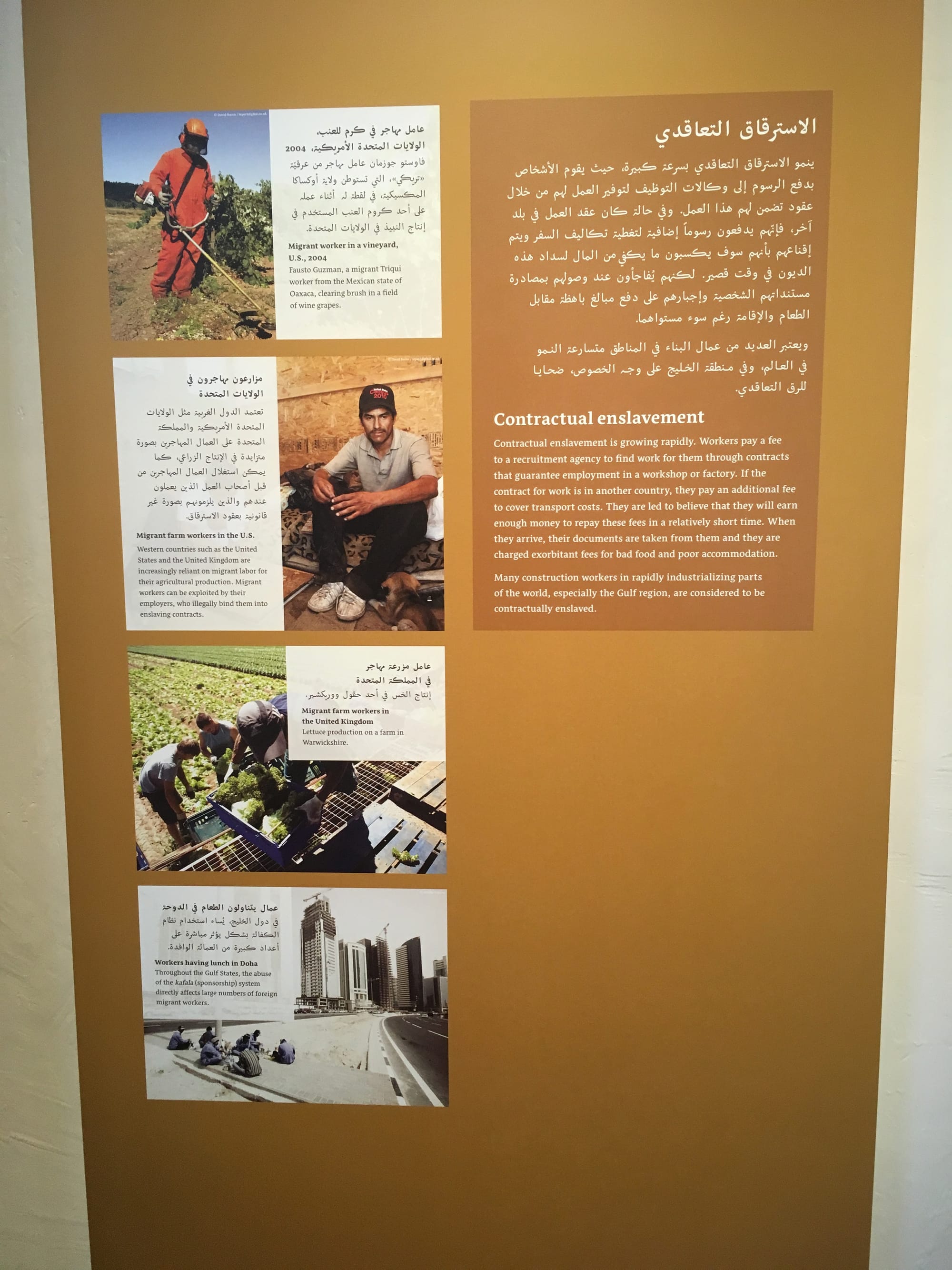

Memories of enslavement are often silenced and yet suffuse everyday life in the Gulf. As governments across the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries memorialize a maritime, pre-oil Indian Ocean past as part of their nation-building projects, the Bin Jelmood House—a museum in the heart of Doha—st