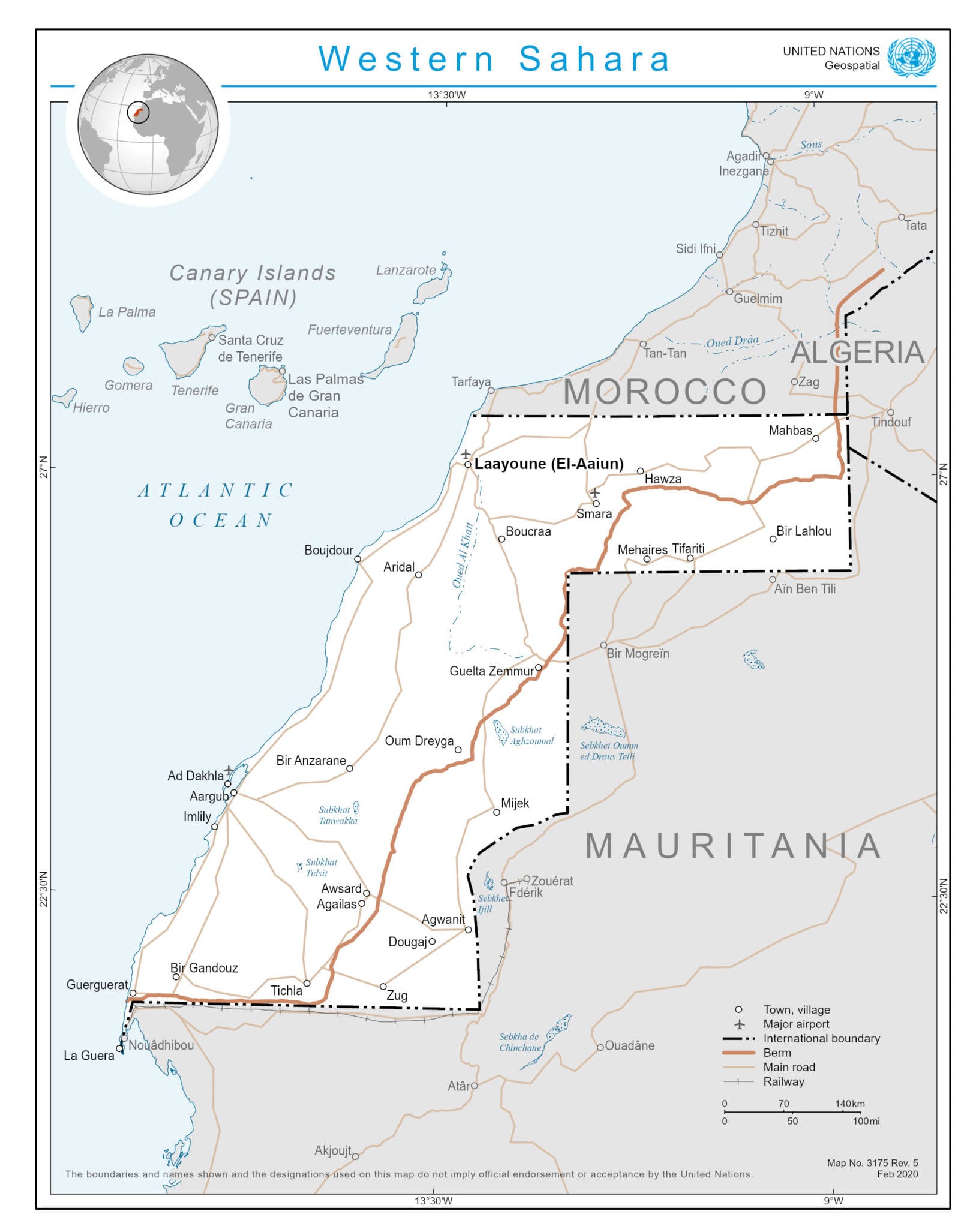

An Invisible War in Western Sahara

War has broken out in Western Sahara and few have heard the news. At a crossroads between sub-Saharan Africa and North Africa, the Saharan desert has long been misconstrued in colonial discourses as a largely unpeopled geography deemed culturally marginal and largely assimilable to Maghrebi post-col