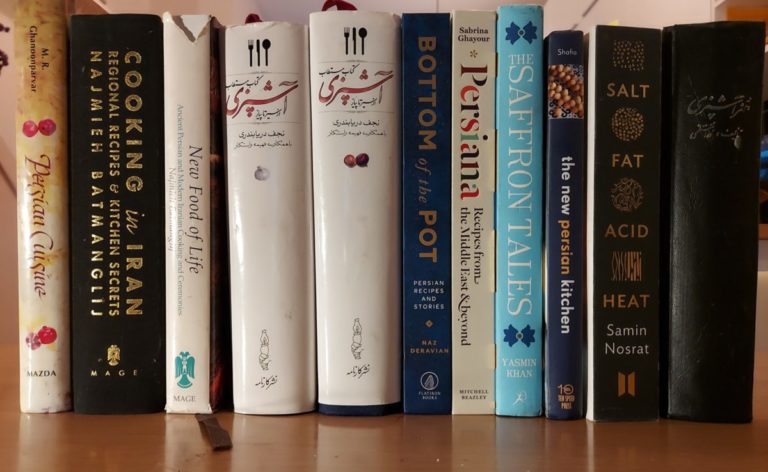

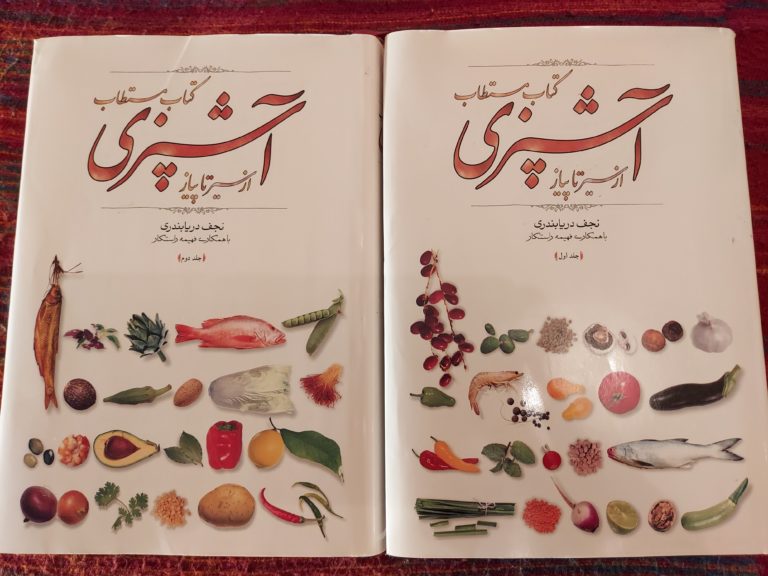

Najmieh Batmanglij, New Food of Life: Ancient Persian and Modern Iranian Cooking and Ceremonies (Chevy Chase: Mage Publishers, 2004 (1992)).

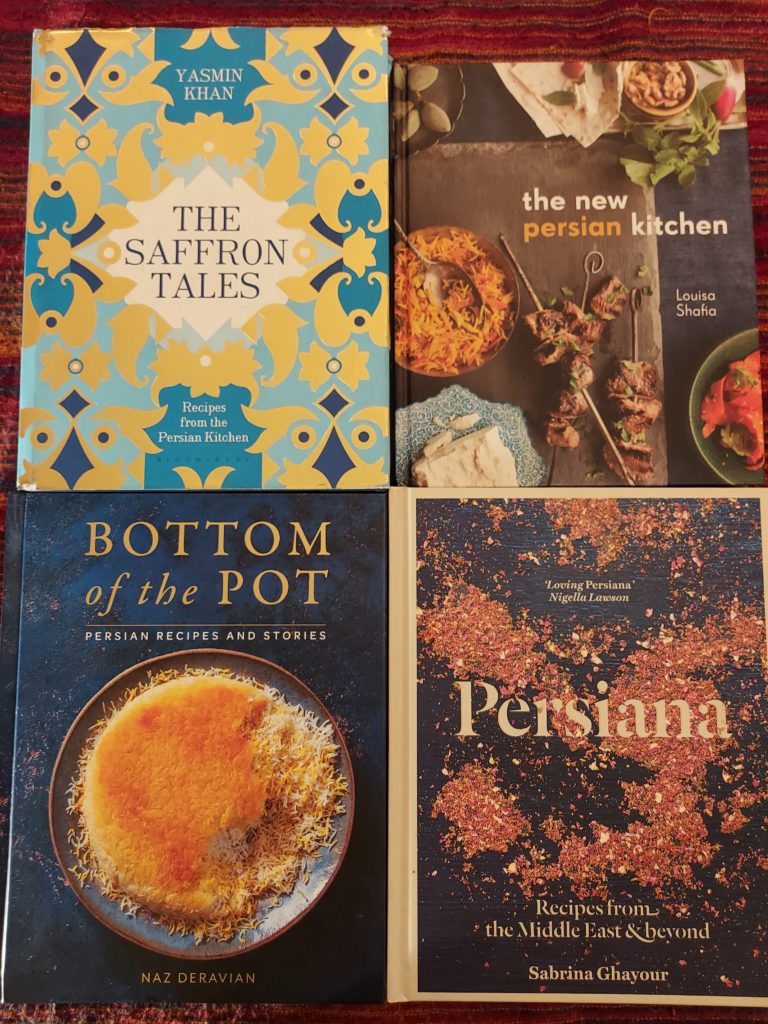

Najaf Daryabandari with Fahimeh Rastkar, Ketab-e-Mostatab-e-Ashpazi: Az Sir ta Piyaz (The Excellent Book of Cookery: From Garlic to Onion; 2 volumes) (Tehran: Mehregan, 2005).

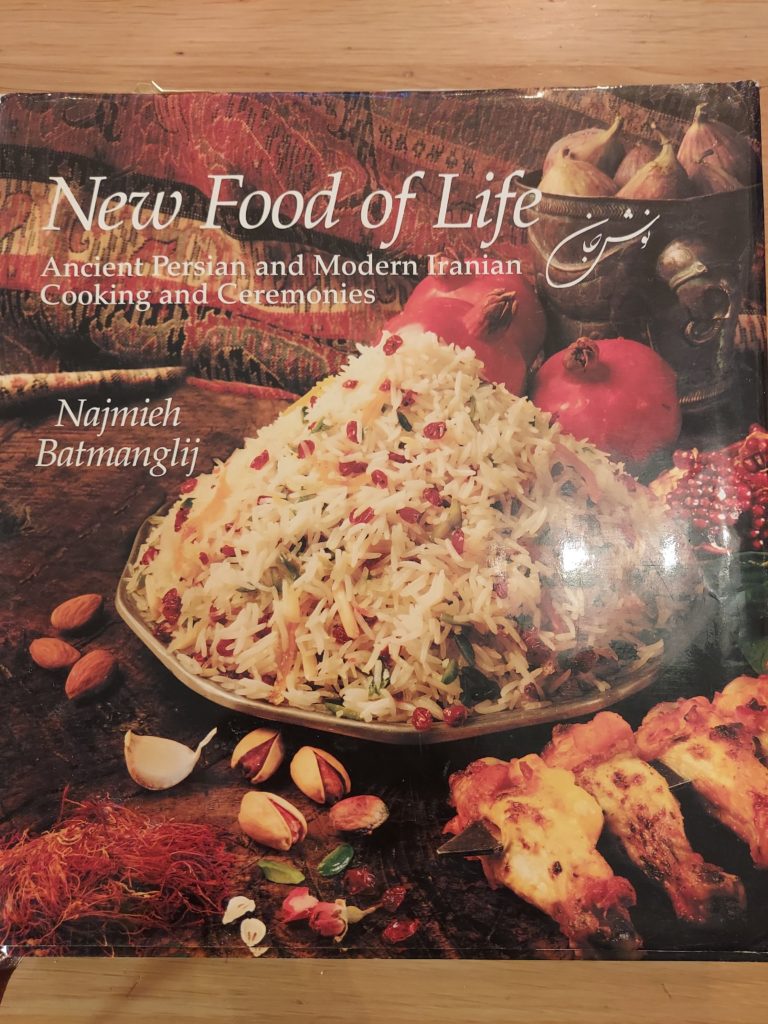

Naz Deravian, Bottom of the Pot: Persian Recipes and Stories (New York: Flat Iron Books, 2018).

Sabrina Ghayour, Persiana: Recipes from the Middle East and Beyond (London: Mitchell Beazley, 2014).

Yasmin Khan, The Saffron Tales: Recipes from the Persian Kitchen (London: Bloomsbury, 2016).

Roza Montazemi, Honar-e-Ashpazi: Majmou’-eye-Ghaza ha ye Irani va Farangi (The Art of Cooking: A Collection of Iranian and Foreign Cuisines) (Tehran: Katibeh, 1985 tenth edition).

Samin Nosrat, Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat: Mastering the Elements of Good Cooking (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2017).

Louisa Shafia, The New Persian Kitchen (Berkeley: Ten Speed Press, 2013).

Margaret Shaida, The Legendary Cuisine of Persia (London: Grub Street, 2000 (1992)).

When I left Iran for good in 1985, I carried two books in my massive suitcase. The first was a boxy little hardcover bound in black cloth: the collected ghazals of Hafez (which apparently every Iranian must own). The version was edited by the great modernist poet Ahmad Shamlu, and it was notorious for his controversial editorial choices, unadorned presentation on the page and blasphemous punctuation. The second book was also bound in black cloth. Roza Montazemi’s venerable cookbook, Honar-e-Ashpazi (The Art of Cooking) was bigger in size but lighter, because its paper was what we called kahi, or lower-quality straw paper, lightweight and liable to yellowing. I am not certain whether my parents had to use their ration books to buy it, but due to shortages of paper during the Iran-Iraq war, the sale of this immensely popular book had to be rationed.

My edition of Honar-e-Ashpazi has some 800 recipes (the 2009 edition of the book has 1700). In my version, approximately 500 of these recipes are farangi recipes: potages, consommés, soufflés, Chateaubriands, schnitzels and a variety of sauces, including béchamel. But all references to forbidden fare are eliminated: no ham, mortadella, sherry, wine or cognac appears in the ingredients’ list. As food historian and cook Anny Gaul has written about Egypt, the emergence of a middle class and its access to a print culture led to cookbooks which Egyptianized modern cuisines, including French recipes. Gaul notes that béchamel sauce entered Egyptian cooking through cookbooks and the restaurant culture.

In Iran’s case, French cookery was absorbed not only through the travels of Iranian aristocrats and merchants to Western Europe and the adoption of French institutions in Iran, but also through the influx of Russian and Polish émigrés after the Revolution of 1917 and two World Wars who brought with them both French court cuisine and their own dishes. It is no surprise that meat pirashkis (pirogis) or Olivier salad—a version of which is called Ensaladilla Rusa in the Hispanophone world or Rus Salatası in Turkey—have been part of the weekly cooking rota of many an Iranian middle-class family. These French and Russian influences were especially prevalent in the kitchens of northern and central Iran, but less so in the south, where the cuisine looks across the water to Arabia and the Indian Ocean.

Kalam pilau. Photo courtesy the author.

Montazemi’s Iranian recipes have to a large extent become standard recipes by which most middle-class Iranians—and certainly those who learned to cook from cookbooks—construct a meal. Montazemi (born Fatemeh Bahraini), who was from Shahsavar on the Caspian coast and moved to Tehran at an early age, highlighted and universalized northern Iranian recipes. As my extended family is originally from southern Iran, the flavor profiles of our family recipes differ slightly from Montazemi’s recipes for such everyday dishes as eggplant, celery or rhubarb stews, or Islambouli or kalam (cabbage/kohlrabi) pilaus. What I remember as childhood favorites, and what I subjectively consider the standard flavors of these dishes, were prepared by my father. He became our household’s primary cook after he was purged from his University of Mashhad job during the years of the so-called cultural revolution (instigated in Mashhad by Abdulkarim Sorush who went on to become a famous reformist).

The two Persian and nine English-language Iranian cookbooks under review provoke reflections and questions about authenticity and adaptation, the social profiles and memories of cookbook writers and what differences in regional cooking portend politically.

Cooking in the Diaspora

Diasporic Iranian cookery writing has broadly come in two waves: from the 1980s to early 1990s and again in the latter years of the 2010s. The first wave appears in the United States and Britain with the arrival of Iranians after the revolution. The second wave occurs when the children of those original exiles come of age and begin to search for community, belonging and an unreachable Iranian past—unreachable because of the obstacles placed on travel to Iran by both the Islamic Republic and European and American governments. The first wave includes the two volumes of Mohammad Reza Ghanoonparvar’s Persian Cuisine—based on a cooking show he hosted on local television in Texas and southern California and published in 1982 and 1984 (later combined in the 2015 edition). Ghanoonparvar is familiar to scholars of Iran, and many others, for his decades of teaching Persian at the University of Texas, but perhaps more importantly, for his beautiful translations into English of some of Iran’s most important modern literature (foremost among them Simin Daneshvar’s Savushun).

Margaret Shaida’s The Legendary Cuisine of Persia, first published in Britain in 1992, includes research on the historical roots and travels of Iranian cuisine. Shaida was born in Britain and moved to Iran with her Iranian husband in the 1950s, and the cookbook is based on her experience of cooking Iranian food for more than 30 years. Shaida introduces most recipes with quotes of relevant passages from Iranian poetry, European travelers’ accounts and her own observations and memories.

The second generation of cookbooks resembles a spate of memoirs, novels and travelogues produced by young Iranian-American and Iranian-European women starting in the 1990s. The authors go to Iran—physically or in memory—in search of themselves and the sometimes elusive connections to a place they remember through a mist of sentiment and forgetfulness. In this second wave, food is the conduit for remembering familial and diaspora history, and not only in cookbooks. Marjane Satrapi’s Chicken with Plums and Marsha Mehran’s Pomegranate Soup both use food as a vehicle for storytelling.

In the first generation of diasporic cookbooks, Najmieh Batmanglij’s New Food of Life is the one that made me think about cookbooks as something more than an instruction manual. After I arrived in the United States, I had to learn how to prepare my meals. In Iran, my family had insisted that as a woman I should not learn cooking so I would not “have to wait on some man hand and foot.” Batmanglij mentions that her family also wanted her to concentrate on her education rather than on helping in the kitchen. At most, my contribution to household cooking was to caramelize ten kilos of chopped onions in one session on an Aladdin stove behind our kitchen, in order to earn pocket money to buy books. Since onion caramelized to brown sweetness is one of the most time-consuming elements in the preparation of most Iranian khoreshts (stews), my parents froze packets of the stuff for use during the week.

In the first generation of diasporic cookbooks, Najmieh Batmanglij’s New Food of Life is the one that made me think about cookbooks as something more than an instruction manual. After I arrived in the United States, I had to learn how to prepare my meals. In Iran, my family had insisted that as a woman I should not learn cooking so I would not “have to wait on some man hand and foot.” Batmanglij mentions that her family also wanted her to concentrate on her education rather than on helping in the kitchen. At most, my contribution to household cooking was to caramelize ten kilos of chopped onions in one session on an Aladdin stove behind our kitchen, in order to earn pocket money to buy books. Since onion caramelized to brown sweetness is one of the most time-consuming elements in the preparation of most Iranian khoreshts (stews), my parents froze packets of the stuff for use during the week.

During my first few years in the United States, I asked my parents for recipes in letters or over biweekly phone calls. My father included “scientific” explanations of the various steps of cooking (including the processes of caramelization, when a stew has “fallen into place” and the uses of salt or acidic additives). Montazemi’s cookbook was my reference point for most Iranian dishes (and a few farangi ones too). It was only when I acquired Batmanglij’s beautifully photographed New Food of Life, that my familial ingredients and flavors began to synchronize with cookbook recipes.

Batmanglij’s cookbooks set the standard for, but also distinguished her from, all other English-language Iranian cookbooks. Her first cookbook in English, Food of Life, was published in 1983 (New Food of Life expands on this earlier edition). She has since authored a cornucopia of books—on cooking with children, simplified Iranian recipes, celebration and feast cookbooks, vegetarian meals and on pairing wine with Iranian cuisine. Her recipes are reproducible and offer suggestions for possible adjustments and personal preferences: She is aware of the uneven availability of specific ingredients—a political and economic aspect of cooking—and offers alternatives when possible. Her selection of recipes, though not comprehensive, includes many familiar dishes that appear on Iranian restaurant menus in the diaspora. But Batmanglij’s cookbooks (as all other English-language Iranian cookbooks) differ significantly from their cousins published in Iran, especially in the organization of dishes into different sections and the inclusion of traditional modalities of cooking perhaps taken for granted in Iran.

The New Food of Life categorizes Iranian foods under headings familiar to Anglophone audiences. Although at home, small dishes, relishes, chutneys, pickles and salads are served simultaneously alongside the pilaus and stews, here some of the former are categorized under “Appetizers and Side Dishes.” In Iranian households, soups and the heavier âshes (thick stew-like soups) can serve as main meals and are often eaten as such, but here, as in most Iranian restaurants in the diaspora, they are offered as first courses. Grilled meats, rice dishes, stews, preserves, pickles, sweets and snacks follow in the book. Even though Iranian sweets are often used throughout the day in everyday entertaining at home, here they are listed as the final course of a meal. The book’s back matter includes a useful Persian-English glossary of ingredients and common flora, a list of essential pantry ingredients and a glossary of Persian cooking terms. Perhaps most fascinatingly, it also includes a classificatory list of foods as hot or cold, which is an ancient Iranian classification system for foods and medicines, recorded in Avicenna’s Canon and with similarities to Ayurvedic taxonomies, but absent from most Iranian cookbooks in Persian or English. The recipes are interspersed with poetry, stories and old jokes (especially about Mullah Nasruldin, the trickster and holy fool of folk stories from Turkey through Iran and on to Central Asia). Some sections are prefaced with an account of the historic development of that subset of the cuisine, its significance in Iranian lives, rituals and culture, as well as broader instructions for their preparation.

Cookery Writers and Their Kin

The politics of Iranian cookery writing are often implicit and invoke memories of home and kinship. The prevalence of memory-telling in diasporic Iranian cookbooks is not unique. Diasporic cookbooks are not only about vivification of beloved childhood meals, but also about a kind of salvage, or a reattachment of self to the countries and communities left behind. Among Middle Eastern food writing, Anglophone Palestinian cookbooks most ardently suture memories of loss to food as markers of belonging and community. And inevitably, Palestinian food writers have to reclaim many of the foods that Israeli writers and chefs have claimed as their national dishes.

The insistence on the use of “Persia” (instead of Iran) in the title of all but Batmanglij’s cookbooks gestures at another set of diasporic politics. Yasmin Khan is explicit as to why: “For most non-Iranians, ‘Iran’ is more commonly associated with the country’s recent political history.” (7) Persia, on the other hand, is associated with luxury: Persian cats, Persian rugs, Persian caviar. And as such, most of the books have Persia—or Persiana, Persian kitchen or Persian recipes—prominently on their covers.

The insistence on the use of “Persia” (instead of Iran) in the title of all but Batmanglij’s cookbooks gestures at another set of diasporic politics. Yasmin Khan is explicit as to why: “For most non-Iranians, ‘Iran’ is more commonly associated with the country’s recent political history.” (7) Persia, on the other hand, is associated with luxury: Persian cats, Persian rugs, Persian caviar. And as such, most of the books have Persia—or Persiana, Persian kitchen or Persian recipes—prominently on their covers.

Samin Nosrat’s book Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat and her joyous eponymous Netflix series are not about Iranian cooking as such but include a great many Iranian techniques and recipes. She was trained at the storied Chez Panisse and took formal cooking lessons, but she begins her story by remembering her family’s migration from Tehran to southern California. Her mother’s stories and recipes appear often, while in the series Nosrat cooks rice with tahdig (crispy bottom layer) with her mother. The book’s section on acid summons Iranian palate’s love of sour ingredients and condiments: torshis (pickles), Omani dried limes, juice of bitter oranges and unripe grapes and Iranian limes (which are closest in fragrance and flavor to calamansis). Nosrat wanted to film the acid episode of her series in Iran but was unable to do so because of sanctions on Iran, so she shifted her travel itinerary to Mexico. Nosrat’s explanations of the alchemy of cooking remind me of my father’s scientific instructions about Iranian cooking.

Only Sabrina Ghayour, whose cookbook is the least beholden to ideas about authenticity of flavors or remembered tastes, admits that although she grew up in an Iranian family (albeit one where no one in the household “really knew how to cook”), she considers herself British. (6-7) She includes such recipes as Spice Salted Squid and Seared Beef with Pomegranate and Balsamic Dressing in her cookbook, which are more inspired by Iranian flavor profiles and not necessarily found in an average Iranian cook’s repertoire. Her book is a Middle Eastern cookbook, not really an Iranian one, even if it is called Persiana.

Authenticity and Adaptation

The vexed question of authenticity haunts the Anglophone Iranian cookbooks. What counts as authentically Iranian or Persian? The more a cookbook claims to be authentic, the more purist it becomes in determining what is considered part of the Iranian canon of cookery. And the more it claims this form of purity, the less it includes the varieties of foods that have been adopted and adapted by Iranians. These foods may have familiar Euro-American names—hamburgers, pizzas, spaghettis—but their flavors are idiosyncratically, peculiarly, deliciously Iranian. For example, Iranian spaghetti is cooked not with Italian herbs but with turmeric, and some Iranian pizzas are dipped in locally produced ketchups, which taste different than Heinz. Many of us grew up eating “kalbas sandwiches” alongside sandwiches of turmeric-tinged lamb’s brain. However, only Ghanoonparvar includes the kielbasa baguette, a mainstay of light dinners or a meal on the run in Iran and sold at most sandwich shops in its halal version even after the revolution. But including an Iranian style kielbasa sandwich is likely considered inauthentic and thus excluded from most cookbooks, even if this so-called inauthentic meal is part of the culinary repertoire of Iranians at home and abroad.

Perhaps because the Iranian diaspora is so politically riven, the longing and loss expressed in Iranian cookbooks avoid explicit political positions. If there are any hints of where the cookbook author stands, they lie in the invocation of wine drinking (robustly banned by the Islamic Republic) and in firmly situating Iran’s potation history as inseparable from viticulture. In Ghanooparvar’s book, historian Rudi Matthee sketches a history of wine drinking in the Safavid and Qajar courts. The essay ends by asserting the centrality of wine drinking as a symbol of “libertinism and freethinking, in contradistinction to the arid formalism of official religion.” (265) Though much of Iran’s classical poetry—by Hafez, Omar Khayyam, Mowlana Rumi and others—praises wine for its literal and metaphorical bounties, middle-class drinkers in Iran are more likely these days to imbibe smuggled Johnny Walker Black and non-alcoholic beers doctored-up with yeast for that final step of fermentation.

It is striking that almost all the cookbooks published in the second wave of publishing in the late 2010s are authored by middle-class women, most of them culinary professionals. Batmanglij is Iran’s greatest Anglophone cookery writer and runs cooking classes in Washington, DC. Shafia also teaches cooking in Tennessee. Ghayour and Khan have both authored a number of Middle Eastern cookbooks. Deravian’s book grew out of her successful blog. Nosrat is perhaps the most prominent, with her Netflix series and perch at the New York Times, where her Iranian recipes sit alongside carefully explicated methods of cooking the basics of world cuisine, from tahini sauce to pasta dough. These women are joined in cyberspace by at least a dozen others who record their experimentation with and experiences of Iranian cooking.

The Politics of Regional Cooking

Where the cookbooks are not about memory-telling, they are about a kind of salvage: rescuing recipes from not only oblivion but also the homogenization of regional variations. Batmanglij’s encyclopedic Cooking in Iran and Yasmin Khan’s trimmer The Saffron Tales both roam over Iran’s regional cooking geography. For both, traveling through Iran and documenting recipes are acts of recuperation and return, in Batmanglij’s case after 39 years of absence. In celebrating the breadth of Iranian regional cuisine, they are however, preceded (and dare one say, surpassed) by Najaf Daryabandari and Fahimeh Rastkar’s two-volume Ketab-e-Mostatab-e-Ashpazi (The Excellent Book of Cookery), published in Iran in 2005. Daryabandari and Rastkar’s cookbook is considered, by most Iranians familiar with it, to be the definitive collection of Iranian recipes.

The two volumes of Ketab-e-Mostatab-e-Ashpazi (The Excellent Book of Cookery) by Najaf Daryabandari and Fahimeh Rastkar.

Daryabandari was born in Abadan and grew up in Bushehr, on the southern coast of Iran. He was an accomplished translator of Faulkner, Beckett and Hemingway into Persian. He came to cookery-writing in prison, where he was incarcerated because of his activities with the socialist Tudeh party after the Shah’s 1953 coup d’etat. In prison he cooked for his dormitory comrades to pass the time. Ketab-e-Mostatab, like Montazemi’s Honar-e-Ashpazi, includes a great many Western recipes, but felicitously also includes Indian, Afghan, Arab and Turkish ones. In the first 430 pages of Volume I, the book includes chapters on Indian, Turkish, Arab, Chinese, Japanese, Spanish, Italian, French and Russian cuisines. These are followed by absorbing essays on ingredients, spices, different kinds of meat, fish, dairy, greens, rice and stock. Ketab-e-Mostatab has an amazing 138 chapters and a vast range. The confidence and egalitarianism with which Iranian recipes are described in their regional diversity alongside Asian and European recipes distinguishes this book from all its Anglophone cousins. The range of recipes nears comprehensiveness, and the humor and self-knowing didacticism are a joy.

Ketab-e-Mostatab is not only about rescuing regional variations in Iranian classics. It is also about the kinship of regional Iranian cuisine with one another and with similar recipes across the world. One of the delicacies I remember from my childhood is my grandmother’s breakfast of mahyaweh (or mayveh, as my family called it). Mahyaweh is made by drying out motu fish (a Gulf version of anchovies) in the sun, powdering it, and mixing it with herbs and spices according to regional or family recipes. My grandmother would add mountain avishan (the southern Iranian equivalent of Palestinian za’atar) and the seeds of sesame, caraway, coriander and nigella. The mahyaweh powder is mixed with oil or eggs, brushed on flatbread, fried and served wrapped around spears of cucumber and Iranian mint. Mahyaweh is impossible to find outside southern Iran and even most northern Iranians do not know what it is. In her cookbook, Khan describes partaking of a street snack in Bandar Abbas that sounds somewhat similar to mahyaweh, but she never names it and only mentions “the dank smell of the sea” as she eats it. (190) Daryabandari and Rastkar, however, include a recipe for mahyaweh in their book, along with a sly discussion of whether the fish is fermented before it is transformed into mahyaweh (if the fish is fermented, Ketab-e-Mostatab cites a religious scholar, the dish is forbidden). In their book, the regional variations of mahyaweh sit alongside tuna-mayonnaise, sardine Iranian-style and ceviche.

On my first visit to Kuwait, I was thrilled to find street-food vendors, many of them of Iranian origin, selling mahyaweh wraps. The circulation of cuisines through trade (with Asia and East Africa), labor migration (mostly of southern Iranians to the Gulf emirates) and enslavement and resettlement (of East Africans on the southern coast of Iran) created entire culinary cultures in the south that are largely disconnected from the foodways of northern Iran. Legacies of Aryanism, racism and self-Orientalizing all mean that these southern culinary cultures are less known, valued and celebrated than their counterparts further north.

Abgousht with accoutrements. Photo courtesy the author.

Ketab-e-Mostatab stands in stark contrast to the Anglophone recipe books. If Daryabandari and Rastkar look southward and to the east, the Anglophone cookbooks—and Montazemi’s—look primarily to the north and to European cookery. Even Batmanglij’s venerable Cooking in Iran is literally and figuratively weighted in favor of northern Iran (only around 150 pages out of 700 cater to the entirety of the southern coast). The rich culinary traditions of the Arab-Iranian southwest, the Afro-Arab and Afro-Iranian south, and Baluchi and Sistani southeast are not researched as deeply, and the recipes here are fewer in number, less complex in their makeup (for example, a grilled fish or a familiar qelyeh stew, rather than the range of preparations I remember from my youth) and less exciting. Other cookbooks’ framing stories condescend to the region. Khan describes southern flavors as an “assault on the senses” when compared to the “delicate” cooking of the rest of Iran. (189)

Since moving to Britain, I have noted the diasporic interwovenness of Iranian cuisine with those of its West Asian neighbors far more than I had in the United States. Iranian restaurants in London often serve the city’s large Arab and South Asian populations. Iranian groceries can be found in Arab supermarkets and vice versa. The Turkish greengrocers in my East London neighborhood carry the Iranian fruits and vegetables that are so hard to find elsewhere: green almonds, greengages, varieties of pomegranates, even the sweet lemons, bitter oranges and Jahromi dates that are mainstays of Shirazi tables. That said, the two or three regional Iranian restaurants in London serve the cuisines of northern Iran.

I now read cookbooks as much for the politics they contain as I do for the pleasures of cooking. As I read, I seek out culinary connections across the waters of the Gulfs and the Indian Ocean. The paucity of such connection in so many Anglophone cookbooks is itself the evidence of a submerged politics. Even before the fickleness of publishing trends and prejudices of editors and publishers shape what books can reach the readers, the regional politics of Iran at home and abroad shape these cookbooks. As they incorporate memories and stories, they become more than an instruction manual. But even at their most austere and functional, politics structures what is included and what is not; how recipes are organized; what ingredients, cooking styles and histories are deemed worthy and gathered under the banner of Iran; what is considered authentic and what audience is offered the whole palimpsest of Iranian cooking. The same overt and unspoken exclusions, the same class and regional allegiances that have shaped Iranian nationalism across the decades, at home and abroad, also subtly refract through the choices by authors and readers of which recipes to collect and how to cook them.

[Laleh Khalili is professor of international politics at Queen Mary, University of London and an avid cook.]