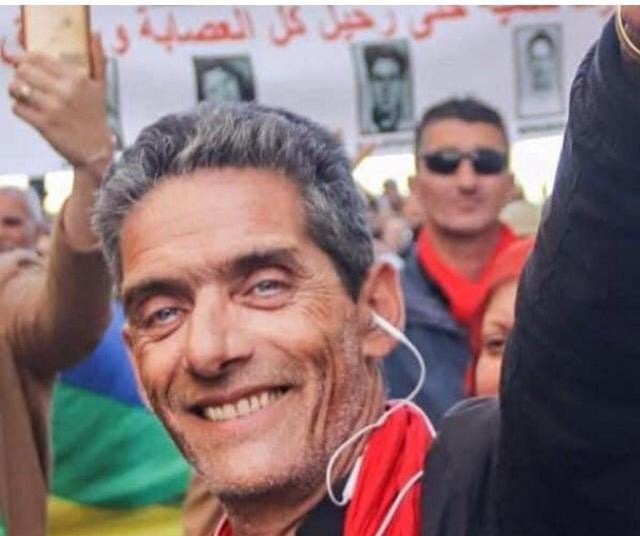

The Algerian Hirak Between Mobilization and Imprisonment - An Interview with Hakim Addad

Hakim Addad has been a political activist in Algeria for decades. In this interview with Thomas Serres he discusses the increasing repression of peaceful demonstrators under President Tebboune, the positive role of a new generation of activists in the Hirak movement, his arrests and imprisonment and