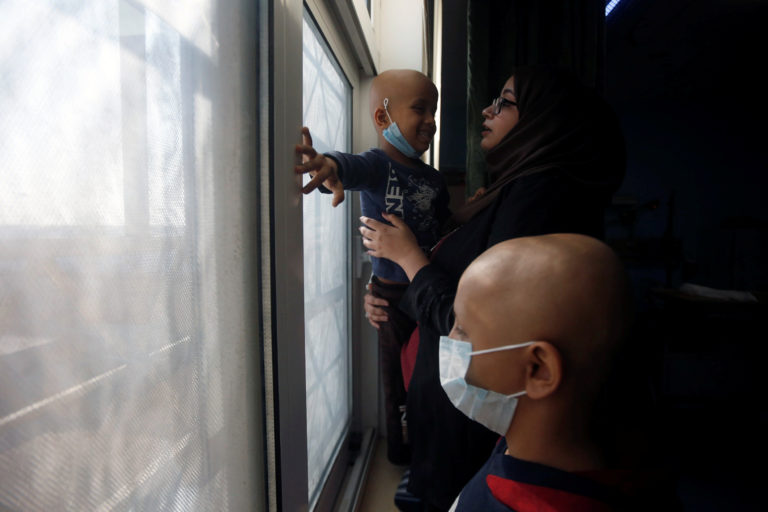

Iraqi cancer survivor Sabrin Abdul-Zahra carries a child also afflicted with the illness as part of a vow to help children after her own suffering, at a hospital in Basra. January 2020. Essam Al-Sudani/Reuters

A number of stories in major international papers have highlighted Iraqis’ resistance to quarantine procedures, their refusal to wear protective gear in hospitals, their failure to report to the hospital before it is too late and their propensity for violence against medical professionals who fail to cure their loved ones. The same reports suggest various explanations. One New York Times story claimed unconvincingly that the problem is rooted in tribal and religious norms, noting that the “aura of sinfulness surrounding the virus” in Iraq had reduced compliance with quarantine.[1]

But this attention to civilian (mis)behavior has ignored the population’s vast accumulated knowledge around epidemics. Iraqis are deeply experienced when it comes to navigating diseases that seemingly spare no one. Indeed, in Iraq it is often said that every family includes someone with cancer—a disease that first entered the public consciousness as an epidemic soon after the 1991 Gulf War and raised concerns around the potentially carcinogenic impact of depleted uranium weapons.

The country’s three-decade experience with cancer provides insight into the question of why many Iraqis treat Ministry of Health and hospital instructions related to the coronavirus with a heavy dose of skepticism. A core reason lies in the failure of the state and political class to manage the country’s cancer epidemic on both preventative and curative fronts by neglecting to address the war-related environmental causes of cancer as well as the deterioration of oncology care.

This tendency of families to rely on their own knowledge and practices around disease is now applied to a pandemic with distinctly different characteristics and pressures. For example, when reports of oxygen shortages circulated across Iraq in June of this year, family caregivers of COVID-19 patients in certain hospitals responded by identifying distribution channels that would enable them to pile up oxygen tanks next to their patient’s hospital bed.[2] While doctors have expressed dismay that such actions generate chaos at a time when a coordinated response is needed, this practice clearly draws from years of experience navigating war-related deficits in the medicine and equipment necessary for treating leukemia, breast cancer and other life-threatening illnesses.

The failures at the heart of the Iraqi medical system to adequately cope with the coronavirus pandemic cannot be blamed on the actions of families for the sake of their patients. It is instead the disorderly and self-serving rule of the political parties ushered into power after the US-led invasion that is the cause of the ineffective response. This elite was targeted by a wide spectrum of Iraqis in the 2019–2020 protests against corruption that unfolded just before the outbreak of the pandemic. Notably, Iraqis suffering from cancer also joined those protests, visibly displaying their breathing masks, bald heads and wheelchairs for all to see. One cancer patient held a sign proclaiming “Corruption Stole My Treatment.” It is not surprising that patients who blame the actions of the ruling political class for the absence of proper treatment for one epidemic would distrust that same political class to manage the devastating impact of a global pandemic.

The Cancer Epidemic Emerges

Cancer has been explicitly linked to the overall decline of the Iraqi population’s health for nearly three decades. In the 1990s and early 2000s, the rising number of cancer cases in Iraq provoked a heated debate about what caused the epidemic. Officials from the Iraqi Ministry of Health made the case to both the Iraqi public and the international community that cancer numbers were rising due to a clear and narrowly defined causal agent: the use of depleted uranium munitions during the 1991 Gulf War by the United States.

The capacity to provide for the nourishment and health of the population, including the management and control of disease, has been central to the logic of state power since the founding of the modern Iraqi state in the 1920s.[4] When Saddam Hussein’s Ministry of Health began to lose its ability to provide high quality public services in the 1990s due to sanctions, the state was left politically vulnerable. With cancer as a powerful and internationally comprehensible symbol, the government’s message to the Iraqi population (and the world) was that the blame lay elsewhere: The US-led war and international sanctions had simultaneously caused cancer and destroyed the health care system.

The US military responded to these accusations with a narrow reading of the scientific data on depleted uranium. Pentagon spokesman Kenneth Bacon said during the height of the controversy in 1998: “We do not believe that a normal exposure to these munitions causes cancers, and have found nothing to confirm [Iraqi claims].”[5] Much hinges on how normal exposure is defined. In the leadup to the 2003 invasion, US military officials repeatedly rejected concern over depleted uranium based upon a study conducted by the British scientific academy The Royal Society. Yet this study calculated “excess risk” from hypothetical depleted uranium exposure scenarios based purely on estimated war-time exposure for soldiers, not the long-term exposure experienced by civilians who live in the environment where the toxic munitions were abandoned. While the study’s authors concluded that the cancer risk would be minimal for soldiers in the battlefield, they recognized that the consequences of long-term exposure to civilians remained highly uncertain.[6]

Meanwhile, cancer patients in Iraq were left to languish amidst a growing disease burden and severe deficits in care. In 2000 the BBC reported that Iraqi doctors called the leukemia ward at the Saddam Central Hospital for Children the “ward of death” with its mortality rate of “100 percent” due to shortages caused by the sanctions. In the face of these deprivations, families started to develop the knowledge and networks necessary for sourcing medications and obtaining access to treatment, which included navigating black markets and cross-border distribution channels.[7] The gradual process of shifting the burden of care from medical institutions to the family and community had begun.

Interpreting Cancer After 2003

In the years following the 2003 US invasion of Iraq, the story of depleted uranium and cancer did not disappear from scientific and journalistic attention. For the political elite and government, however, the stakes of the epidemic faded. The Iraqi state—with its corresponding obligations to society at large—devolved into fractious and competing rival political parties, each of which had specific economic interests, territorial spheres of influence and patronage networks.[8] An epidemic that for years had been portrayed as a threat to the Iraqi population as a whole did not align with the parochial political agendas of the post-2003 era. In addition, with the US-led coalition showing little commitment to protecting or rebuilding state medical infrastructure, the Ministry of Health and its assets became sites of predation for emerging (and armed) political parties, particularly the Sadrist faction and their military wing, the Mehdi Army. The complex network of state-run hospitals deteriorated rapidly between 2003 and 2007. Scores of doctors—including oncologists—fled the country due to workplace intimidation and violence by rival militias, lack of equipment and pervasive corruption.

While cancer fell off the political map during the post-2003 era, at the level of society both the practices and discourses around the disease underwent rapid and far-reaching transformations. The cancer narrative of the pre-invasion Ministry of Health—which sought to tie the emergence of the epidemic to a specific toxin imposed by a particular foreign military—ceased to hold sway over a population that increasingly regarded the sources of toxicity as layered and fragmented across different iterations of war and various political and military actors.

This societal awareness of the layered legacies of toxicity tracks closely with recent scientific findings by Iraqi and international researchers, which has detailed the health impacts of a broader set of toxins beyond depleted uranium.[10] Since 2010, scientific production on cancer and environmental exposure in Iraq has gradually gained traction after years of dormancy. Several recent studies have explored cancer rates and environmental exposure not only in southern Iraq but also in areas uniquely impacted by the US-led invasion in 2003.[11] One study noted the “increases in cancer and infant mortality which are alarmingly high” in Falluja and named depleted uranium as “one potential relevant exposure.”[12]

But, overall, ordinary Iraqis place little faith in the current state of science in the country—and particularly its capacity to inform and shape policy. In the hallways and waiting rooms of hospitals, discussions of causal agents were often intermixed with expressions of uncertainty and despair due to the total inability of the state to understand and manage the epidemic. The perceived decline of science—and consequently the overall impossibility of certainty—was discussed in mournful tones, suggesting a strong latent societal attachment to a history of medical and empirical rigor. One patient from Basra, the owner of a small clothing shop, noted: “It could be the bombings, or the bread, or even the smoke from the oil fields. We need studies but…[pausing] Iraq is finished.” Even to this shop owner without a university education, the death of science and the end of Iraq went hand in hand.

Until local and international teams of scientists are granted the resources to develop more comprehensive investigations, ordinary Iraqis have no choice but to survey the environment for potential dangers and carcinogens by using their own faculties of perception. Importantly, local understandings of toxicity are both regionally segmented and flexible according to the ongoing progression of war and conflict. For example, with the rise of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) in 2014, patients from the areas affected by the conflict incorporated these realities into their understanding of the disease. In interviews at Kirkuk Cancer Hospital (an oncology center hosting many displaced persons from ISIS-occupied areas) during 2016, a 39-year old homemaker and breast cancer patient noted: “The unclean environment in my area, Hawija, is contaminated with the smoke generated by shelling ISIS, and this could be a reason for cancer. Due to power outages at night, we have to sleep on the roof of our house. When we wake up in the morning, we obviously notice that the color of the kulla, which is a cloth cover we put around us in order to protect ourselves from the stings of insects, has changed from white to dark black.”

She also identified the possible impact of horror experienced during her escape from Hawija as well as grief sedimented over years of war and the loss of a brother in 2003. Powerful emotions are thought to erode the body’s defenses, further pointing to the multiple overlapping legacies of war that take a toll on the body. Now residing in Kirkuk city, she remained vulnerable to the encroachments of the conflict, alleging that both doctors and everyday citizens treated her “inhumanely” due to associations between her home region and ISIS, and that this environment of suspicion has impacted her capacity to cope with and heal from cancer. But she insisted that her situation was simultaneously unexceptional: “All Iraqis are living under this pressure. A filthy hospital. A doctor who doesn’t treat you like you’re human. The politicians selling medicine for profit. In Iraq the situation is tired,” she lamented. For this breast cancer patient and many other Iraqis, the sense of toxicity goes far beyond physical pollutants. Iraq’s material and moral environments were both polluted by decades of war and the neglect of the political class.

New and Improvised Pathways of Health Care

For most Iraqi cancer patients, the search for the right health care is a disastrous and confusing experience. Obtaining cancer care in post-2003 Iraq increasingly requires traveling across the country and region. Prior to 2003, the pathway of referrals was relatively straightforward and managed systematically. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy required referrals to Baghdad, Mosul or Basra. After the US-led invasion, as these cities descended into violence and hospitals deteriorated, families with cancer patients started considering a wider range of options. Cities in the semi-autonomous and relatively stable Kurdish region developed public oncology centers that rivaled those in Baghdad, compelling many patient trajectories northward to Erbil and Sulaymaniyah in addition to cross-border hubs such as Beirut and Istanbul.

Because of the need for mobility, Iraqis do not have the luxury of relying upon contacts within their limited tribal, familial or sectarian group. Hospital waiting rooms and hotels next to oncology wards become sites where patients and caregivers from across Iraq exchange numbers and contact details in the event of both present and future needs. In Sulaymaniyah’s oncology hospital, for example, I witnessed how patients draw upon each other’s region-specific resources: An Arabic-speaking patient from Baghdad may need help from a Sulaymaniyah-based Kurd in applying for residency, while the Kurd may need a certain medication to be brought from Baghdad.

Such cross-regional and cross-sectarian relationships are not purely organized around transactional modes of assistance. As the interview with the breast cancer patient from Hawija indicated, there is a recognition among Iraqi cancer patients that the deterioration of medical institutions has stripped hospitals not only of their technical capacity but also of their moral resources, with doctors becoming run down and impatient under the pressure of decades of neglected facilities and corruption. As doctors have become largely incapable of caring for “the state of the soul”—which many Iraqis insist constitutes “half the treatment”—families have to look elsewhere to provide this crucial dimension of care. Family caregivers often comment that enjoying a laugh with strangers across the oncology ward allows patients to momentarily forget the disease—along with the other troubles of life in war—and thereby retain the fortitude necessary for healing.

Constant movement between provinces and across borders is exhausting and financially costly.[13] Patients who sought out consultations in multiple hospitals and provinces were often seeking verification during particularly critical moments in the treatment trajectory. One breast cancer patient noted: “I was seeing a doctor in Baghdad, but then he advised a mastectomy, and I thought, this is Iraq, the doctors don’t have good equipment, I need another opinion. And so then I came to Erbil, and he said you don’t need a mastectomy. And so at this point I was confused. I checked with some friends and another doctor in Baghdad and finally did a consultation in Beirut, and I took the advice of the Beirut doctor back to Baghdad for treatment.” Patients often attempt to arrive at relative confidence about a certain trajectory by drawing upon a cross-regional set of diagnostic tools and judgements.

Increasingly these pathways of care have had to contend with the politicization of access. Iraqi oncologists are often at pains to assert that they receive and treat patients impartially. But from the perspective of the patient, care need not be refused by the hospital for it to be inaccessible. Particularly after the defeat of ISIS in 2017, a fragmentary array of armed groups that are spread out across the central and northern provinces have established checkpoints, rendering mobility across and between provincial treatment hubs impossible for those lacking the right political affiliations or connections. Moreover, at the level of the hospital itself, politicized triage often transpires in subtle ways. Most cancers require treatment over a long period of time, meaning that the ability to secure consistent access to the full range of required pharmaceuticals and examinations is vital. During the period of ISIS control over Mosul, oncology hospitals in nearby Erbil and Sulaymaniyah saw a surge in patients from Mosul and other affected cities. Such displaced patients were almost never refused care outright, but were often compelled to purchase significant portions of their chemotherapy medications while local residents were granted the full range of doses from public supplies. It is for this reason that often the poorest and most politically vulnerable patients in Iraq can be found in the expensive treatment centers of Beirut and Istanbul: Though costs are crushing, at least they are provided predictably.

Cancer and COVID-19

Journalistic accounts of Iraq’s ongoing COVID-19 crisis suggest that ordinary citizens are resistant to quarantine and the testing regime due to tribal practices and culturally shaped notions of stigma. But the more important and widespread phenomena is that Iraqis have grown accustomed to improvised modes of seeking care that often involve circumventing the advice of doctors out of distrust of the system and heavy reliance upon family, friends and even strangers across provinces to provide technical assistance and moral support. Iraqis are not skeptical of medicine in an absolute sense. Their skepticism is historically specific and has developed in reaction to war-related deficiencies and the politicization of health care. They are also not dismissive of the need for rigorous scientific verification before definitively determining the causes and extent of disease. But in the absence of a state committed to the health of the population and corresponding scientific production, they are left to live under the uncertain shadow of numerous potential material pollutants in addition to moral defects in the social environment—all of which are seen as causing or exacerbating disease.

In the context of COVID-19, the Ministry of Health ignored these lived realities and proceeded as if they were operating in a country where societal trust in the state’s capacity to understand and manage epidemics was intact.

If the Ministry of Health seeks to improve patient compliance with COVID-19 protocols and those for future epidemics, health officials cannot treat the problem as one of technical or cultural incompetence. The core of the problem is societal distrust that grew over years of war and neglect of the health sector. One positive development is that Iraqi doctors are increasingly acting in public solidarity with their patients against the political class. During the October 2019 protests, thousands of Iraqi doctors took to the streets in their white coats to highlight the corruption and neglect by the political elite of the health sector and the detrimental impacts on patient care. Until grassroots pressure leads to meaningful reforms, however, Iraqi families facing COVID-19, cancer and other diseases will likely continue to rely upon their own networks and practices for managing and responding to serious illness.

[Mac Skelton is director of the Institute of Regional and International Studies (IRIS) at the American University of Iraq, Sulaimani and visiting fellow at the London School of Economics Middle East Centre.]

Endnotes

[1] Alissa Rubin, “Stigma Hampers Iraqi Efforts to Fight the Virus,” The New York Times, March 14, 2020.

[2] “A Difficult Day for Corona Patients in Iraq and Warnings of a Second Wave,” Al-Jazeera, June 28, 2020. [Arabic]

[3] A. Yaqoub, et.al., “Depleted Uranium and the Health of People in Basrah: Epidemiological Evidence; The Incidence and Pattern of Malignant Diseases Among Children in Basrah with Specific Reference to Leukemia During the Period of 1990–1998,” Medical Journal of Basrah University (MJBU) 17/1,2 (1999). Quote from James Ciment, “Iraq Blames Gulf War Bombing for Increase in Child Cancers,” BMJ 317 (December 12, 1998).

[4] Omar Dewachi, Ungovernable Life: Mandatory Medicine and Statecraft in Iraq (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2017).

[5] James Ciment, “Iraq Blames Gulf War Bombing for Increase in Child Cancers,” BMJ 317 (December 12, 1998).

[6] Royal Society, “The Health Hazards of Depleted Uranium Munitions,” May 22, 2001.

[7] Hayder Al-Mohammad, “What Is the ‘Preparation’ in the Preparing for Death?” Current Anthropology 60/6 (2019).

[8] Mac Skelton, Zmkan Ali Saleem, “Iraq’s Political Marketplace at the Subnational Level: The Struggle for Power in Three Provinces,” Conflict Research Programme, London School of Economics and Political Science, London (2020).

[9] James Mac Skelton, Cancer Itineraries Across Borders in Post-invasion Iraq: War, Displacement, and Geographies of Care (Doctoral dissertation, Johns Hopkins University, 2018).

[10] Ahmed Majeed Al-Shammari,”Environmental Pollutions Associated to Conflicts in Iraq and Related Health Problems,” Reviews on Environmental Health 31/2 (2016).

[11] R. A. Fathi, L. Y. Matti, H. S. Al-Salih, and D. Godbold, “Environmental Pollution by Depleted Uranium in Iraq with Special Reference to Mosul and Possible Effects on Cancer and Birth Defect Rates,” Medicine, Conflict and Survival 29/1 (2013).

[12] C. Busby, M. Hamdan and E. Ariabi, “Cancer, Infant Mortality and Birth Sex-Ratio in Fallujah, Iraq 2005–2009,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 7/7 (2010).

[13] Mac Skelton et al, “High-Cost Cancer Treatment Across Borders in Conflict Zones: Experience of Iraqi Patients in Lebanon,” JCO Global Oncology 6 (2020).