Downtown Amman bird market, May 2012. Photo by the author.

There are three major types of bird markets: auctions that sell breeds to be admired for their craftsmanship, street markets that sell pigeons to fly for the hobby called qshash hamam (the practice of flying birds in a flock at dusk from rooftops) and brick-and-mortar pet shops that specialize in pet birds. Each of these markets attracts customers of a specific class. Street markets are patronized by the working class, the brick-and-mortar shops serve the middle class and the newer pigeon auctions attract patrons from the upper-middle class. Auctions, which have sprung up in the last five years or so, distinguish themselves from the street markets by cultivating elite pigeon breeds. International bird trade regulated by the Jordanian Ministry of Agriculture is officially permitted, but some pigeon enthusiasts in all three types of markets engage in unregulated, illicit trade. Street markets are most commonly associated with such illegal business and are regularly disparaged for it. Upper-middle class bird breeders want no association with the unsavory activity of the pedestrian urban markets because beyond their illicit nature they are also the same live animal markets that have recently been in the news as a source of zoonoses that transmit viruses from animals to humans, including the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

On top of restrictive environmental policies, social conventions in Arab majority societies associate qshash hamam, and by extension all pigeon activity, with the working class and is seen as a pastime akin to gambling. Avian markets, however, pre-date the contemporary environmentalist movement and are as old as the metropolitan capitals of the Middle East. Even as some in Arab majority societies socially disparage these markets, they are also valued for their history. Regardless, afraid of being socially ostracized because of their association with pigeons, the upper-middle class auction participants keep their hobby a closely guarded secret.

Inside the Pigeon Auctions

One night in March 2017, Abbas found his way to the Amman auction while visiting his family from Dubai, where he was a software engineer for a major global technology company based in Seattle.[2] Abbas was a young trim man in his early thirties wearing skinny jeans, a t-shirt and a black leather jacket. This visit he was in town to take care of some dental work, but he typically returned to the city every three months to visit his pigeon flock, which he kept in Amman and paid caretakers to attend.

Dr. Akbar’s Auction, March 2017. Photo by the author.

Inside the auction about a hundred men gathered, smoking shisha and ordering cokes, water and lemonade with mint. The walls were decorated with oversized photographs of Real Madrid, one of Spain’s football teams distinguished by its posh fans.

At the front of the room was Dr. Akbar, the auction organizer and a dentist by profession. Next to him was a large white birdcage fitted with a bare light bulb over the perch to illuminate the lot inside. Dr. Akbar called into his microphone for bids as his assistant gently guided the birdcage on a wheeled cart up and down the center aisle flanked by participants sitting in rows of red velvet-backed metal chairs. Dr. Akbar, who asked not to be identified by name for fear of bringing shame on his family, had started the auction almost six months before. The most expensive bird of the evening, a dewlap, went for 1,000 JD but was worth closer to 5,000 JD, Abbas estimated. Another participant, a breeder named Ra‘ad, turned to me and said, “I’d never sell my birds here because I wouldn’t get what they are worth.” Instead, Ra‘ad preferred private, closed-door transactions with his buyers. Ra‘ad spent his childhood in the United States, but now lived in Jordan. Birds were his passion. That night he bid 600 JD on the dewlap.

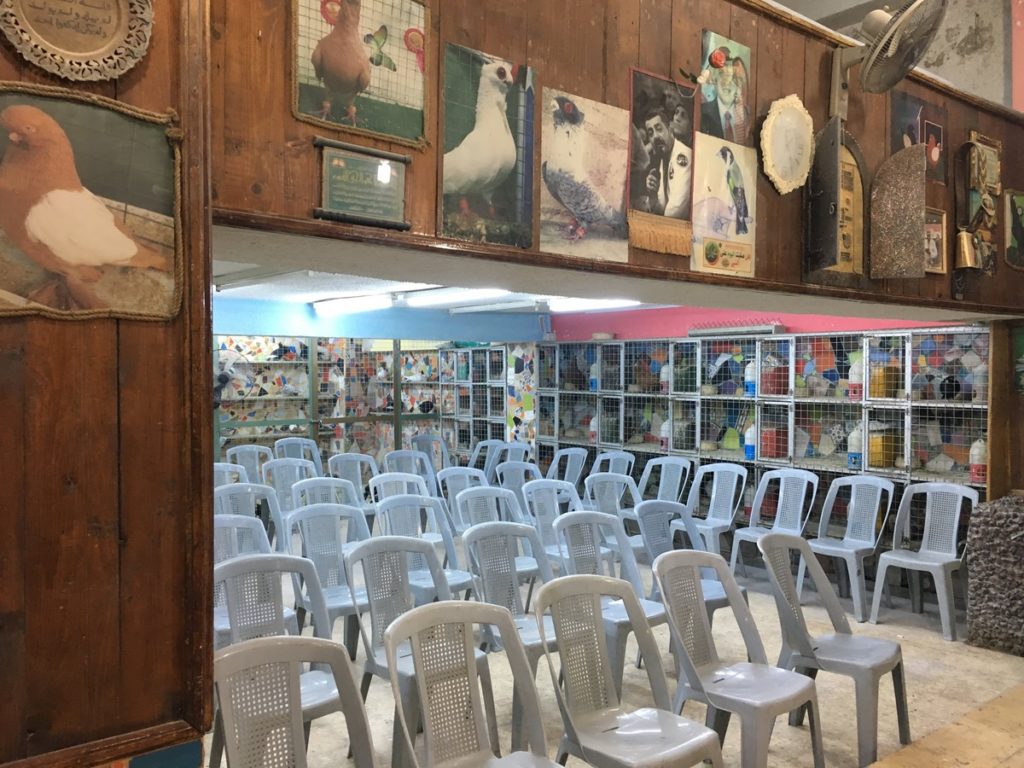

Across the city, in Ras al-Ain, Ghalib Malik runs an even larger affair on Thursday nights where hundreds gather to bid 5–10 JD on more affordably priced birds. He hosts the auction in his bird shop that opens out into the Roman amphitheater where he sells pigeons as well as tourist souvenirs like brass Arab coffee pots, watercolor scenes of Iraq’s marshes, rotary dial telephones, old radios and swords in engraved sheaths—all blanketed with a healthy layer of dust. Patrons visit Malik’s market for his birds, though, not his tchotchkes.

The Ambiguous Status of the Friday Bird Market

In addition to his auction and shop, Malik, like other bird store owners, frequents the weekly street market that operates every Friday just before prayers near the old Italian hospital. For years, the only way to find this illicit market was through word of mouth. Vendors set up their stalls on a small side street in front of a row of shops closed on Fridays. Jordan’s Royal Society for the Conservation of Nature (RSCN), as the implementing partner for CITES and in an effort to curb animal trafficking, also sends scouts to survey the Friday bird market.

Ghalib Malik’s Auction, May 2019. Photo by the author.

Amman’s pigeon breeders claim the Ras al-Ain market is 100 years old and was established during the waning years of the Ottoman Empire. They also say that the best pigeons came from Syria before the civil war began in 2011, due to Syria’s proximity to Turkey and the long Ottoman history of keeping menageries and trading in exotic animals. Bird markets are a common feature of every Middle Eastern metropolis—from Baghdad, where breeders suggest the markets date to Caliph Mansour’s founding of the Abbasid capital, to Beirut, Ramallah, Cairo and Dubai. These bird markets chart a trade geography that has endured for centuries but exists today mostly through subterfuge. Despite attempts at international regulation, bird markets continue to be robust regional economies that connect Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Iraq and Gulf countries like Yemen and Oman through unauthorized trade despite the fact that these countries are CITES signatories.

Jordanian environmentalists tasked with enforcing CITES whom I spoke with in 2012 commonly told me that they first learned to appreciate birds by attending informal markets with their fathers. Their paternal introduction to pigeon-breeding indicates that this love of birds begins within families and bonds sons to fathers. As one might expect, Jordanian environmentalists expressed mixed feelings about their role in policing these markets; on the one hand, they now recognize the international problem of trafficking, on the other, they have fond memories of sharing the market experience with their fathers.

Sometime in the last few years, the Greater Amman Municipality installed a large street sign that reads Suq al-Tuyuur (the bird market) to mark its location. Officially, the government of Jordan may be a CITES partner, but unofficially, in Arabic, the municipality has embraced the long-standing cultural phenomenon of the bird trade.

Suq al-Tuyuur sign in Downtown Amman, March 2017. Photo by the author.

The Bilad al-Sham Pigeon and Artisanal Breeding

The breed of pigeon known as Bilad al-Sham is named for the region of Greater Syria, an area that historically included Syria and Lebanon. Jordanian breeders are considered some of the best cultivators of the Bilad al-Sham breed. These pigeons vary in stature, plumage and coloring, but all birds of this breed are characterized by the singular feature of their elongated neck, rising two to three inches from body to head. Breeders consider Shami birds to be one of the most beautiful breeds because it can be enhanced and modified by the breeder to produce distinct aesthetic results. When a pigeon enthusiast looks at the bird, they see the bird but also the breeder’s artisanal skill.

The name of the Bilad al-Sham breed of birds represents an undivided geography that existed before the Ottoman Empire was dismantled and which could be seen as embodying an unrealized Arab regional unity. Still, Nasir, one of the Thursday auction participants, insisted the birds are decidedly apolitical: “As bird breeders we don’t think of Bilad al-Sham as a political imaginary, we think of the birds as a hobby.”

Ghalib Malik’s shop and auction, March 2017. Photo by the author.

At auctions and markets, pricing is determined by an individual bird’s aesthetics, which are considered a physical manifestation of both the individual’s genetic composition and the breeder’s expertise. One bird breeder, Rami, told me in his downtown Amman shop that he learned how to breed through experience and experimentation. When I asked if he used specific textbooks or methods, Rami replied, “We don’t want the next generation just to memorize, to follow books and script. We want them to experiment and be creative while breeding the birds.” I asked Rami if he considered breeding to be an art form. No, he said, bird breeding is not an art, it is a skill, insisting that breeding is a form of expertise with a methodology to be studied, learned and mastered over time.

Back at the Thursday auction at Victor’s Cafe, Ra‘ad explained that prices for higher value birds would be corroborated by an appraisal from a recognized expert breeder. By his account, bird breeding is an artisanal practice that produces both expert knowledge of genetic recombination and a citizen science perfected outside of recognized scientific institutions. Breeders like Rami and Ra‘ad understood pricing as a negotiation between buyer and seller and, thus, a material representation of that relationship. In their experience, pigeon cultivation generated a sense of belonging to a continuous region undivided by state borders.

Class Identity at the Market

Within this avian economy, human engagement with birds is indicative of class identity according to the three primary bird market types: the street markets, private shops and the auctions. At street markets, like the one in downtown Amman, where lower priced birds are sold, vendors repurpose cardboard boxes to display their stock and hand over individual birds to buyers in paper bags. These urban markets are the least reputable places to buy birds because, aside from being unregulated by the state, they are also foundational for qshash hamam, which is commonly associated with the unemployed or underemployed. Pigeon owners who practice qshash hamam are known to attempt to lure birds away from other neighboring flocks as they circle the skies, which contributes to their reputation as mendacious, corrupt and corruptible. It is commonly said in Amman that a pigeon handler’s testimony in a Jordanian courtroom will only be accepted if it can be corroborated by another witness.

Brick-and-mortar shops are the intermediary station of the bird economy. These shops in downtown Amman have storefronts and signs that designate their position in the formal economy and make them a more reputable location for procuring birds. Within this category there is also a range: There are the pigeon storefronts of Amman’s downtown that are one step above the street markets and there are the glossier commercial markets of Jebel Amman where everyday middle class residents might shop for a parakeet or a pair of lovebirds. Owners of the shops that sell pigeons move between the world of the street market and the world of the auction and participate in both. The store in turn offers a space for bird patrons to also move between these separate venues and distinct social worlds. Rami, who owns a shop, sells some of his lower-priced birds at the street market and vends his higher-quality breeds at the auction. Birds sold at these shops command anywhere from 5 JD to 4,000 JD. The business is a profitable one: Rami typically earns between 500–1,000 JD a month, sometimes up to 3,000 JD. While he might lose 500 JD in another month, in any given year he does not earn less than 12,000 JD, which is considerable given that the World Bank estimates that in 2018 Jordan’s Gross National Income per capita was 2,977 JD ($4,200).

At the highest end of the spectrum, the top of the market hierarchy, are bird auctions and closed door, private transactions. Here too, there is a range of type: Where Ghalib Malik’s large auction also includes the sale of comparatively low-priced birds at 10 JD per pigeon, Dr. Akbar’s auction across town concentrates on the sale of mid- to upper-priced birds that range from 50 JD to 1,000 JD and into the tens of thousands.

Birds have historically also been used as military technologies, including by the British in Mesopotamia prior to World War I when their covert operations across southern Iraq relied on carrier pigeons. Today, the military campaigns of militia groups, including terrorist operations, similarly employ birds. In Syria, various anti-state militias, including the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS or Daesh in Arabic), relied on carrier pigeons to transmit messages. Birds were the analog back channel of these contemporary covert operations much as they were a century ago.

Similar to the class variation found in different bird markets, militia groups seem to reveal their class orientation through their choice of birds to cultivate. Al Qaeda’s bird practices demonstrate a radical difference in leadership and orientation from ISIS. Osama bin Laden was a known falconer, a practice cultivated within his family as one of the wealthiest and most established in Saudi Arabia. Once, in the 1990s, Osama bin Laden’s falconry practice sheltered him from US military attack. When US counterterrorism expert Richard Clarke testified to Congress during the September 11 commission hearings, he indicated that President Bill Clinton had the opportunity to take military action against bin Laden, but did not because he was with an elite falcon hunting party from Dubai that included members of royal families considered US allies.

Jordan is well aware of the links between birds and terrorism. In May 2016 the Jordanian state put a 2-week moratorium on the import of birds because they had intelligence that ISIS was trying to send covert messages with their flock. Despite this fact, bird cultivation is certainly not a correlate or a precursor to violence.

Rather, avian-human relationships are so common, so definitive of families, of class groups, of both urban and rural social life that human relationships with birds are essential to everyday life in the Arab majority world. The fact that families fleeing the Syrian civil war have re-established bird markets in Jordanian refugee camps reveals the importance of these markets within communities and can be seen as an expression of hope for a better future.

At Victor’s Café in Amman, Jordan’s elite pigeon enthusiasts like Abbas and Ra‘ad disavow any political or military connection to birds. Nasir emphasizes that pigeon breeding and collecting is a hobby, an “escape from reality,” a way to momentarily disappear from the world and its problems to become immersed in a pastime that celebrates the magnificence of birds. Environmental regulations may falter, nation-states may face challenges to their control of cross-border trade, but well into the foreseeable future Abbas, Ra‘ad and other pigeon enthusiasts of the Arab majority world will still be flying birds.

[Bridget Guarasci is an assistant professor of anthropology at Franklin and Marshall College.]

Endnotes

[1] Names of individuals referred to by first name only, and names of businesses, are pseudonyms.

[2] All quotes and observations are from my fieldwork on bird markets and auctions in Amman, Jordan conducted intermittently between December 2011 and May 2019.