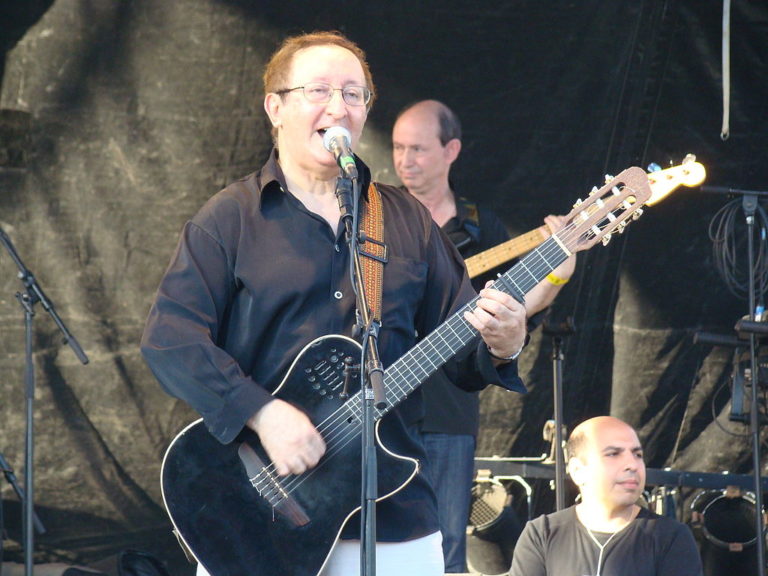

Idir in concert in Bondy, France, for Fête de la Musique, 2008. [Photo by Suaudeau, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.]

Kabylia as a Stronghold of Resistance

Idir was a product of his time and of his environment but he ultimately transcended both. He was born in 1949 in colonial Algeria. As a child, he witnessed the atrocities of the French colonial system and the horrors of the Algerian revolutionary war (1954-1962). The post-independence military regime of the National Liberation Front (FLN), however, marked him even more profoundly and helped shape both his persona and his engagement with politics.

During French colonial rule, Kabylia (the Berber region of Algeria) was a site of repeated resistance—including Fadhma N’Soumer’s rebellion against early occupation in 1857, the insurrection led by Shaykh El Mokrani and Shaykh Belhaddad of the Rahmaniyya Sufi brotherhood in 1871, the FLN’s organizational Soummam Congress in 1956 and Colonel Amirouche’s military campaigns during the war of national liberation from 1954–1959. Immediately following independence in 1962, Hocine Aït Ahmed, one of the local heroes of the revolution, took up arms against the FLN’s single-party tyranny. The uprising was crushed and successive FLN governments pursued Arabization policies, repressed the Berber language (Tamazight) and cultural rights and economically and politically controlled Kabylia for the next 40 years—even as individuals from the region did achieve some measure of educational and professional success and sometimes high positions within the state administration.

Kabyles continue to resist marginalization. In what became known as the Berber Spring in 1980, young Kabyle men and women took to the streets following the cancellation of a lecture by the celebrated writer Mouloud Mammeri on ancient Kabyle poetry in Tizi Ouzou. The demonstrations were violently suppressed but they inspired a series of general strikes across the region. Two decades later, in what became known as the Black Spring of 2001-2003, Kabyles responded to ongoing socioeconomic oppression, and the military gendarme’s killings of local residents and activists, by re-occupying the streets and demanding greater equality and social justice. Idir’s songs provided the musical amplification of this decades-long fight for the protection of Kabyle rights and the recognition of Tamazight as a national and official language, not only in Algeria but also across North Africa and the diaspora.

The Protest Singer

Like Bob Dylan and Joan Baez, Idir knew that the artist must sometimes be politically engaged and use his artistic talent to fight against all types of oppression and injustice. By using lyrics and music to convey the pain and suffering of his people, Idir became more than a singer; he articulated the conscience of his people.

Song has long played an important role in the Berber resistance movement. Idir, along with other Kabyle singers, such as Ferhat, Matoub Lounès, Meksa and Aït Menguellet, engaged in protracted political combat, not just for identity and language, but also for social justice and economic equity, earning them the title of “les maquisards de la chanson” (the freedom fighters of song), by the celebrated Algerian francophone writer, Kateb Yacine. These singers animated a burgeoning set of Berber cultural associations, which mushroomed both in Algeria and abroad in the wake of the Berber Spring. Most notably, the Berber Cultural Movement (Mouvement Culturel Berbère, or MCB), has been especially active through its various branches. The branch situated within the large Kabyle diaspora in Paris where Idir lived most of his adult life, is active in organizing conferences on Berber culture, music concerts, exhibits and evening courses to teach younger generations Tamazight and their ancestral region’s history. Idir played an important role in unifying the movement, knowing how to navigate its various fractures which were to emerge in the 1990s along the lines of the two major Kabyle political parties: Aït-Ahmed’s Socialist Forces Front (FFS) and Saïd Sadi’s Rally for Culture and Democracy (RCD). Idir understood very well that political fracture only helps the oppressor. As he explained to the South African singer Johnny Clegg in a televised conference, “a song is worth more than a thousand speeches.” [1]

Between the Singular and the Universal

Idir’s fights against exclusion and injustice extended beyond Algeria. As a resident of France since 1975, Idir was sensitive to the issues affecting French society, particularly ethnic diversity and the conditions of emigrant minorities. His albums Identités (Identities, 1999), La France des couleurs (France of Colors, 2007) and Ici et Ailleurs (Here and Elsewhere, 2017) feature duos with renowned French singers and sports celebrities from diverse origins, such as Henri Salvador, Charles Aznavour, Obispo, Noa, Patrick Bruel, Yannick Noah and Zineddine Zidane. These albums celebrate the ethnic and cultural diversity of France at a time when French politics and segments of the media continue to create and feed off discourses of exclusion, hatred and racism.

In this sense, Idir brought Kabyle culture to the world stage.[2] Outside of North Africa, most people don’t understand his song lyrics. But they immediately feel that his melodies incarnate something indescribable that is often profoundly sad and melancholy. The song Avava Inouva, which has since been translated into more than 15 languages, is a Berber lullaby based on a tale that recounts a family evening gathering in Kabyle villages across centuries. Idir was nourished by the oral tradition of his native Kabylia, where women played an important role in preserving the rich Kabyle poetry. As a young child, Idir was surrounded at home by women who spent time chanting songs and poems. This ancient Kabyle poetry with roots in past centuries has been handed down through scores of generations, thanks to oral traditions. By combining these ancient tales and tunes with modern music, Idir managed to enthrall Kabyles and non-Kabyles alike.[3]

Indeed, Idir’s strength resides in his unique capacity to reconcile the particular and the universal. While he incarnates his local Kabyle culture and identity, his songs speak to millions of people around the globe. In the second phase of his career, Idir included world-class singers, such as Charles Aznavour, Manu Chao, Maxime Le Forestier, Francis Cabrel and Enrico Macias, among many others, to sing in Tamazight. While the Algerian authorities persisted in banning the Berber language on its own soil, Idir put it on a global platform. In an interview with the francophone newspaper, El Watan on July 2, 1999, he stated: “The fact that other artists come to me is a recognition of my culture, whereas others closer to me do not recognize me. My culture has existed for millennia, I am Algerian, I don’t know how to be something else, but even though the country has been independent since 1962, I’m not recognized as an integral part of this country. It is a discomfort that I carry within myself.”

A True Supporter of the Hirak Movement

Idir’s support for socially just causes never faltered. When asked about his opinion on the 2019 popular revolts in Algeria, known as the Hirak, Idir said that, “I loved everything about these marches: the intelligence of these youths, their humor, their determination to remain peaceful…I confess that I lived these moments of grace, since February 22, as a breath of fresh air. I’m diagnosed with a pulmonary fibrosis, so I know what I am talking about. We are doomed to succeed, anyway. So, let’s continue thinking about the progress of the Algerian nation. If we remain united, nothing and no one can defeat us.”[4]

Idir understood the importance of this popular movement, which now includes all Algerians, Kabyles and non-Kabyles, together in a peaceful attempt to end the old regime once and for all and thus open a space for Algerians to recreate their own sovereignty and be at last masters of their own destiny. Algeria must build on its rich diversity, not on the old system of exclusivist politics and centrist rule, which characterized Algeria before and after independence. Each and every group (be it ethnic or religious) must find its rightful place in this new nation. Algerians can coexist in peace, instead of killing each other as they did during the “black decade” of the 1990s, a brutal period of Islamist insurgency and military counterinsurgency. But Algeria must first find its true identity, fully acknowledge its long history, accept and respect its Berber heritage along with those of other minorities and finally break off the shackles of a monolithic Arabo-Islamic ideology, which has been preventing the nation from attaining its deserved grandeur. These changes are precisely what Idir dreamed and hoped for.

From his humble beginnings to the last moments of his life, Idir remained faithful to himself and to his diverse audiences. Hamid Cheriet has passed away, but Idir, as his Kabyle name signifies, will live forever.

[Nabil Boudraa is professor of French and Francophone Studies at Oregon State University. His most recent publications include Algeria on Screen: Society, Culture and Politics in the Films of Merzak Allouache (Cambria Press, 2020) and a special issue of the poetry review Pacifica on the Kabyle poet-singer, Lounis Ait Menguellet.]

Endnotes

[1] Idir-Johnny Clegg, a capella (Vis à Vis, Point du Jour), France, 1993. Documentary, 55 minutes.

[2] Jane Goodman, Berber Culture on the World Stage: From Village to Video (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005).

[3] Idir’s success as a singer was purely accidental. Avava Inouva is a song that he wrote for the famous Kabyle singer Nouara. When she did not show up for a live radio show, he was asked to play the song himself at the last minute. The song became an instant hit. He decided to change his name to Idir as a way to hide his new career from his family since singing as a public performance was taboo in Kabyle tradition at that time.

[4] Journal du dimanche, April 19, 2019. Author’s translation.