The Turkish invasion of northern Syria, with President Trump's acquiescence, illustrates Turkish President Erdoğan’s authoritarian populist penchant for treating foreign policy as an extension of domestic crisis management. But it will only further aggravate the interlinked economic and political problems facing the AKP-led government—regardless of whether Erdoğan wins his war on the Kurds of Rojava.

The Turkish invasion of northeastern Syria in October 2019 alongside its Syrian allies, code-named Operation Peace Spring, has been portrayed by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan as a defensive and humanitarian campaign. Its official goal is to create a “safe zone” along the Turkey-Syria border by expelling those that Turkey considers terrorist organizations in order to allow Turkey’s Syrian refugee population to move back to their own country. Erdoğan further claimed that the campaign will bring stability, peace and democracy to northeastern Syria. Far from defensive or humanitarian, however, Turkish Armed Forces and its Syrian proxies are attacking what is arguably one of the most stable, tolerant and democratic regions in the entire Middle East—the Kurdish enclave of Rojava—which had been experimenting with a new form of radical democracy with a feminist, ecological, secular and ethnic-pluralist worldview.

Erdoğan’s Syria offensive is not the first time he has rallied the public around the Turkish flag against so-called Kurdish terrorists as a response to emergent domestic crises of his own making, but it may be the most consequential thus far in his 17-year reign. Turkey's severe structural economic problems of debt, inflation and monetary crisis have burst the bubble of Erdogan’s neoliberal populist economic strategy and damaged his ruling Justice and Development party’s (AKP) electoral clout. The harm has been amplified by the momentous loss of Istanbul and other metropolitan cities in the July 2019 municipal elections. Erdoğan has gambled that Turkish chauvinism can provide the glue to piece back together his hegemony and allow him to avoid, for the moment, confronting the economic crisis.

Operation Peace Spring, while illustrating Erdoğan’s authoritarian populist penchant for treating foreign policy as an extension of domestic crisis management, will only further aggravate the interlinked economic and political problems facing the AKP-led government—regardless of whether Erdoğan wins his war on the Kurds of Rojava.

The Economic Crisis That Never Was

Despite Erdoğan’s repeated insistence that “there is no crisis [in Turkey], but only international manipulations,” Turkey is currently experiencing one of the most serious economic crises in its modern history. The origins of this crisis have less to do with alleged foreign manipulations and more to do with the structural contradictions of the AKP’s neoliberal populism, which may have now reached its limit.

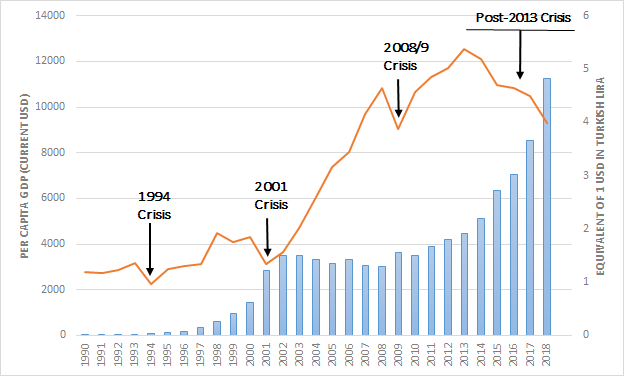

Both Erdoğan and President Donald Trump maintain that Turkey’s economic difficulties emerged in August 2018 after Trump doubled US tariffs on steel and aluminum to pressure Erdoğan into releasing the evangelical pastor Andrew Brunson, which put downward pressure on the Turkish lira. But the Turkish lira had been losing its value against the US dollar since 2008, and even more rapidly since 2013 (see Figure 1). Hence, the causal relationship is the other way around: Because the Turkish economy had been confronting deep structural problems since 2013, it has become extremely vulnerable to external “manipulations.”

Basic macroeconomic indicators reveal the severity of the crisis unfolding since 2013. Per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which was above $12,000 in 2013, has fallen below $10,000 in less than five years. From 2013 to 2018, inflation in consumer prices rose from 7.4 percent to 16.4 percent—food prices in particular have been skyrocketing and threaten the livelihoods of millions of people. Turkey’s unemployment rate is also at a record level—14 percent of the total population and close to 30 percent of youth—unseen since the 2008 global financial crash. Moreover, real wages are at a record low because the AKP government dismantled organized labor by bringing trade union density from approximately 30 percent to single digits within the first decade of their rule. In addition to all these economic difficulties, the rapid influx of approximately 3.6 million Syrian refugees and their super-exploitation by local Turkish firms is driving the wages of the working classes down to unprecedented low levels.

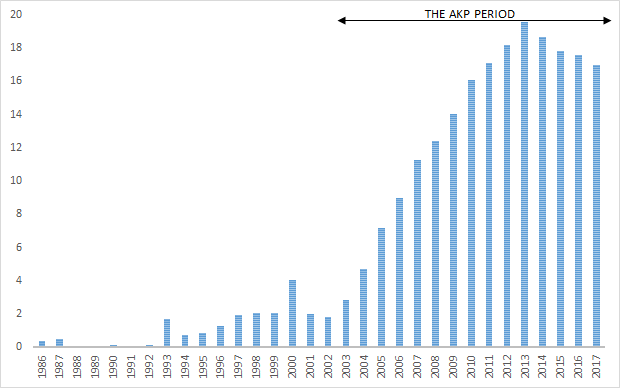

Under such financial strain, millions of Turkish people now depend on direct monetary or in-kind aid by the government as well as on the availability of consumer loans and credit cards for their livelihood. For over a decade, the AKP has distributed such aid and free services to their low-income followers through local governments and municipalities under their control. In addition, since the AKP came to power in 2002, Turkey experienced a rapid accumulation of household debt, which made up almost 20 percent of GDP in 2013 (see Figure 2).

The provision of clientelist aid, consumer credit and loan options to low-income groups is one of the key pillars of the AKP’s neoliberal populist strategy.[1] The Achilles heel of this strategy, however, is that the availability of cheap consumer credit depends on low interest rates, and low interest rates in a semi-peripheral economy such as Turkey depend upon favorable global economic conditions. Luckily for the AKP, such conditions were very favorable from 2002 to 2009. Post-2001 financial reforms under the International Monetary Fund's stand-by program attracted huge capital flows, which helped produce the golden era of AKP rule. While the 2008 financial crisis generated rapid capital outflows from Turkey and produced stagnation in the Turkish economy, the quantitative easing policies followed by the US Federal Reserve helped reverse capital flows back to Turkey. That’s why from 2009 to 2013 the Turkish economy appeared as if it quickly recovered and continued to grow.

But after 2013, as interest rates in the United States started to rise following the Federal Reserve’s tapering announcement, the foreign capital aiding the AKP’s economic miracle went back to the United States. Consequently, interest rates went up in Turkey and many low- and middle-income groups lost access to consumer credit and had to deal with the enormous debt they had accumulated over the years.

Fluctuations in the global economy also deeply affected the AKP’s neoliberal regime of capital accumulation, which was excessively dependent on foreign capital inflows and access to cheap credit.[2] Because foreign loans and credit were not primarily used as investments that would facilitate material expansion of production and trade in the long-run (such as factories or industrial plants) but in activities that produce profits in the short-run (such as construction), the end of cheap credit also struck a blow to the AKP’s ruling strategy.

Under AKP policies, for example, many new companies closely linked to Erdoğan’s family or their political circle quickly became giant conglomerates through over-priced construction projects—including massive airports among the world’s largest (such as the new Istanbul Airport), extravagant bridges (such as Osman Gazi and Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridges), gigantic mosques, expensive roads, mega housing complexes, humongous shopping malls and new luxury hospitals. The overwhelming majority of these lucrative public procurement tenders were obtained in a non-competitive bidding environment, which favored AKP-affiliated firms.[3] Such projects were paid for through cheap foreign credit and government investments in which the AKP government offered prices well above the actual market values, as well as various investment incentives such as tax and custom exemptions and direct monetary subsidies and guaranteed payments in US dollars or Euros. These tenders were one of the ways through which the AKP helped produce a new rival faction of the Turkish bourgeoisie that is politically loyal to the party.

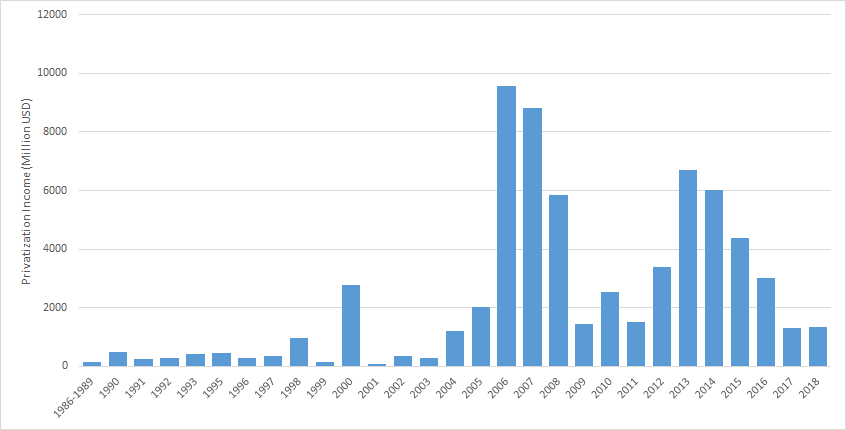

But when cheap credit options disappeared after 2013, followed by the exchange rate crisis, the government could not pay its debt to these private firms, eroding its support and leading to more desperate measures. The crisis was further aggravated by the fact that after generating super-profits through massive privatization schemes from 2002 to 2013, there was nothing left to privatize and those revenues began to rapidly decline (Figure 3).

As a result of these shortages, the AKP government started to rely more and more on predatory forms of accumulation.[4] These included a number of strategies, such as the expropriation of hundreds of major firms and funds that belonged to its political rivals (like the Gülen group). Another strategy was to transfer the funds of municipalities in the Kurdish region to the AKP-affiliated firms by displacing elected mayors via presidential decrees, appointing trustees (kayyum) and establishing lucrative business contracts. A third strategy was to fan the flames of the chaos in Syria with the expectation of gaining control over land and oil resources as well as leadership in reconstruction and development after the civil war.

By 2019, it became clear to many policymakers and economists that the Turkish Treasury was running out of money and that the AKP’s neoliberal populist strategy had reached its limits. With few options to generate or borrow money in order to save AKP-related businesses from the rising tide of bankruptcy, which had already drowned hundreds of firms, the government finally turned to the Central Bank in 2019 to take a number of extraordinary measures. First, it transferred liquidity from the Central Bank to the Turkish Treasury including the transfer of 40 billion lira worth of legal reserves, which the Central Bank had set aside for use in extraordinary circumstances. Second, in July 2019, Erdoğan fired Central Bank governor Murat Çetinkaya from his post.

While this move was widely interpreted as a result of Çetinkaya’s refusal to cut interest rates in line with Erdoğan's heterodox view (shared by most of his populist counterparts) that the way to lower inflation is to lower interest rates, the real reason may lie elsewhere. The Central Bank under Çetinkaya was hardly independent—an AKP loyalist until he was fired, Çetinkaya was repeatedly criticized by liberal economic circles for doing its bidding. And when he was fired, the Monetary Policy Committee of the Central Bank was already planning further interest rate cuts. Çetinkaya probably refused to print more money and to be the leading actor of what would have been a suicide plan triggering hyperinflation and the devaluation of the Turkish lira in another effort to help Erdoğan and the AKP government save AKP-affiliated firms.

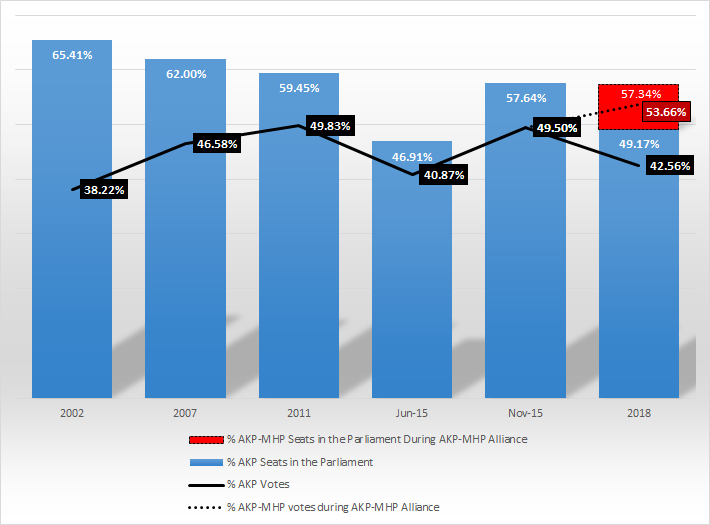

The AKP’s Rising Authoritarianism

The AKP’s economic decline after 2013 has been intimately related to a growing political crisis during the same period—one of the most tumultuous in recent Turkish history. When the global economic environment was favorable, the AKP was the undisputed winner in nearly all general and local elections. From 2002 to 2011, the AKP increased its votes from 38 percent to 50 percent and secured an absolute majority in the Turkish parliament by occupying at least 60 percent of all seats. During this golden decade, the AKP could count on the support of a wide range of political groups, including pro-European Union liberals, center-right conservatives and different factions of political Islam as well as various secular and Islamist nationalist groups. The AKP was also supported by the United States and the European Union as a champion of democracy and a potential model of Islamic democracy for the Middle East.[5]

In its second decade, however, and especially since the end of the favorable global economic environment in 2013, the AKP lost its capacity to mobilize this wide spectrum of political groups and to garner international support. Since 2013, the AKP government has repeatedly been challenged by diverse forms of political contention including social movements from below (the 2013 Gezi uprising), inter-elite feuds (the 2013 corruption scandal), military coup attempts (the failed 2016 military coup) and electoral setbacks. In the June 2015 general elections, the AKP received one of the most serious defeats in its entire history: It lost its majority in parliament and could not establish a coalition government. The AKP lost many seats to the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) which won 80 seats in parliament with 13 percent of the vote, thus becoming the first pro-Kurdish party to pass the 10 percent threshold in the history of Turkish democracy. As a result, Erdoğan called for a snap election in November and publicly announced that if the AKP did not rule the country after this snap election, only chaos would remain.

Indeed, the period between June and November 2015 ended up being one of the most violent and chaotic periods in modern Turkish history. Turkey experienced deadly suicide bomb attacks (often targeting the Kurds and socialist activists), the government re-launched military operations against the Kurdish Workers Party (PKK) and the military launched destructive operations in several Kurdish districts including Sur, Cizre and Nusaybin in the name of fighting terrorism.

The AKP did its best to rally the Turkish nationalist electorate around the flag. In the November elections it managed to increase its votes to 49.5 percent. Capitalizing on the nationalist fervor and violence, the AKP gained back its majority in parliament by securing over 57 percent of the seats and entered an alliance with the ultranationalist Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) against all other parties.

Despite the partial restoration of the AKP’s electoral strength, however, there was no return to normalcy from the war-like state-of-emergency conditions, full-fledged oppression of political opposition and growing authoritarianism. The AKP never fully recovered its electoral strength either. It managed to gain an absolute majority of votes and seats in the parliament only with the help of its ultranationalist ally, thus becoming partially dependent on the MHP.

Losing Istanbul

The final blow in the AKP and Erdoğan’s political decline was struck in the local elections of March 31, 2019 when the AKP-MHP alliance lost control of major cities such as Istanbul, Ankara, Antalya, Adana and Mersin to opposition parties. The most consequential of these losses, however, was that of Istanbul, which the AKP lost twice to the opposition’s “Nation Alliance” candidate Ekrem Imamoğlu despite Erdoğan’s major participation in the second election.

By showing that Erdoğan could be defeated in elections, the Istanbul defeat not only helped the opposition overcome their learned helplessness, but it also showed many AKP leaders that the tables had already turned, triggering the first serious wave of resignations within the AKP. Erdoğan’s authoritarian tendencies had already alienated many liberal and Islamic conservative co-founders (such as the former president Abdullah Gül) who were ready to support an alternative party. After the AKP losses in the 2019 local elections, however, many AKP members across the country—including the former prime minister Ahmet Davutoğlu and an influential co-founder of the party, Ali Babacan—resigned from the party in an attempt to form an alternative center-right political party to challenge the AKP.

The economic loss of control over metropolitan centers—and Istanbul in particular—was catastrophic for the AKP. With a population of 16 million residents (approximately 20 percent of the country’s population), Istanbul is the largest city and the economic capital of Turkey. As of 2018, the mayor of Istanbul had a consolidated budget of approximately 42 billion Turkish lira. For more than a decade, the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality (IMM) under the AKP government was run almost like a family company whereby it used its resources to provide social services and aid to its political clients and also help an AKP-linked faction of the Turkish bourgeoisie to accumulate capital at an unprecedented pace and scale.

When the IMM was involved in social projects, for example, it often did so by providing various in-kind or monetary aid to charitable Islamic waqfs and associations that were affiliated with the AKP. It is estimated that as of 2018 the IMM transferred over 800 million Turkish lira ($145 million) to such organizations, which have become dominant actors in Turkish civil society. The AKP used Istanbul’s massive revenue—together with the revenue of other municipalities and local governments—as a patronage fund to distribute cash to its business partners, to the waqfs and NGOs under their influence, to media outlets and to its followers in order to maintain and preserve its power.

Control over the municipalities was a key component of the AKP’s hegemonic strategy, and thus their loss played an important role in the weakening of the party. It is not a coincidence that Erdoğan repeatedly stated that “who controls Istanbul, controls Turkey” and, “if we lose Istanbul, we lose Turkey.” They were also ready to take extraordinary measures to prevent such an outcome.

Riding the Tide of Chauvinism

Losing the 2019 local elections taught Erdoğan and the AKP government two important lessons that became the basis for the political rationale of Operation Peace Spring. First, the AKP government realized that the overwhelming majority of Turkish society viewed the AKP’s Syrian refugee policy negatively. One of Ekrem Imamoğlu’s election promises was that as an Istanbul major, he would do anything in his power to help the Syrian population residing in Istanbul to go back to Syria. Such a promise meshed well with the rising chauvinism in Turkish society in general and among followers of the AKP-MHP bloc in particular, which helped Imamoğlu to win significant votes from their supporters. Erdoğan and the AKP leaders learned that to win the support of the voters they lost, they needed to come up with a viable solution to the Syrian refugee problem. Many AKP leaders also believed that the reconstruction of cities and towns in Syria could help the AKP-affiliated construction firms to accumulate capital.

Second, the loss of the 2019 local elections reinforced the electoral threat of the Kurds and the pro-Kurdish parties (HDP) in deepening the crisis of the AKP regime. In both the June 2015 general elections and the 2019 local elections, the strategic alignment of pro-Kurdish parties and voters with those of the non-Kurdish anti-AKP opposition proved to be the decisive factor in defeating the AKP. In the June 2015 general elections and the November 2015 snap elections that followed, many Kemalist Republican People’s Party (CHP) followers voted for the HDP knowing that helping the pro-Kurdish party enter the parliament was the most effective way to weaken the AKP. Similarly, in the 2019 local elections and both rounds of Istanbul elections, the pro-Kurdish party followers strategically supported the CHP-İyi Party alliance—two of their historical arch enemies—against Erdoğan’s AKP.

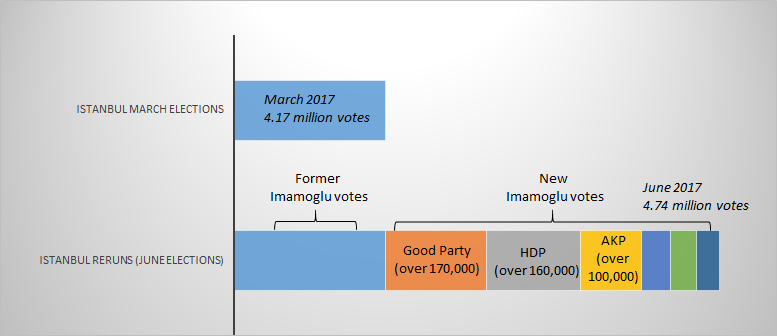

They did so despite the fact that Erdoğan and the AKP managed to get and to publicize a letter from the imprisoned PKK leader, Abdullah Öcalan, stating that the Kurds should stay neutral in this election. They also broadcast an interview with Abdullah Öcalan’s brother Osman Öcalan (officially viewed as a terrorist by the Turkish state) on state television who announced that the Kurds should not vote for Imamoğlu. Yet none of these efforts prevailed. On the contrary, not only did Imamoğlu preserve his support amongst Kurdish voters from March 2017 (estimated to be over 700,000), but over 160,000 new HDP followers who had remained undecided in the March elections decided to vote for him in June. The returns make clear that Imamoğlu could not have won either election without the Kurdish votes.

This lesson is precisely why Erdoğan and the leading AKP cadres made several moves to end the strategic rapprochement between the Kurds and the opposition parties. In order to alienate the Kurds they pursued a strategy of realigning the political parties along the axis of, as they say, “those who defend the interests of the Turkish state” and “those who do not.” Before launching Operation Peace Spring, they had already tested the potential success of this strategy through the purchase of the anti-aircraft S-400 missile system from Russia. Except for the HDP, all political parties supported Erdoğan’s weapons purchase. Simultaneously, the AKP government launched a number of social and political campaigns framing the HDP as an extension of those considered terrorists. In August, the AKP government replaced the newly elected HDP mayors of Diyarbakir, Mardin and Van with their trustees (kayyum) on the grounds that these HDP mayors were aiding the PKK financially and logistically.

All of these political campaigns put the HDP in the spotlight and prepared the broader public to accept Operation Peace Spring. Erdoğan and the AKP government attempted to ease their own political problems by rallying the nation around the Turkish flag against the “Kurdish terrorists,” by pressuring all opposition parties to alienate the HDP and by signaling to the nationalist electorate that the AKP is the only party that can find a credible solution to the Syrian refugee "problem." Moreover, the AKP government also thought that it could mobilize their allies in the construction sector for the reconstruction of northeast Syria as it had already done in northern Iraq and more recently in Afrin (northwest Syria, which is still under Turkish occupation), as well as confiscate Syrian oil as a temporary solution to their economic woes. And even if the campaign is not successful, Erdoğan could use the pretext of ongoing wars against terrorism to explain how and why the state ran out of money and the economy was in such terrible shape.

Nevertheless, it is important to remember that Erdoğan has been waging two wars in Syria: one against the Kurds in northeast Syria that started in October 2019 and one against the Bashar al-Assad regime in general since 2011. Unfortunately for Erdoğan, he cannot win both. Even if he wins the war against the Kurds in Syria, this would probably be at the cost of strengthening Assad and Russian influence in the region, and thus losing the Syrian War. In that case, Russia and Syria will be the beneficiaries of this campaign, not Turkey. Erdoğan’s crises will be waiting for him at the end. Excessive military spending will very likely contribute to the current economic difficulties. Although the ongoing global economic slowdown and the controversial decision by Turkey's Central Bank to cut interest rates provide Erdoğan some additional room for maneuver, he misses this opportunity by insisting on saving the AKP-affiliated firms first, and writing checks that cannot be cashed.

In the political sphere, the rising tide of chauvinism can help Erdoğan attract nationalist votes in the short run, but such a victory will not be sufficient to stop the structural weakening of the AKP. The AKP’s ultranationalist allies, as well as nationalist parties in the opposition, are in a better position to capitalize on Turkish chauvinism. The deepening of the world hegemonic crisis faced by the United States has been providing Erdoğan some leverage in geopolitical negotiations. After all, it was Trump’s decision to pull out from Syria, which is nothing but a confession that the United States can no longer even pretend to be a world hegemonic power, that paved the way for Operation Peace Spring. Yet, Erdoğan mistakes the weakening of US power for the strengthening of his own. Erdoğan believes that he can play one great power (Russia) off another (the United States) in the region. But without a far-sighted and well-crafted diplomatic strategy, his short-term efforts will eventually trap Turkey between these two great powers.

It is almost certain that the Syrian adventure will further alienate Erdoğan and the AKP from the international community and intensify the conflict between the AKP and Kurds in Turkey. Turkey will not be able to provide a solution to the Syrian refugee problem but will experience an additional influx of the jihadist forces from Syrian territories after the Assad regime and Russia gain control over the region. In short, instead of solving Erdoğan’s problems, Operation Peace Spring will probably prepare the conditions of even deeper economic, social and (geo)political crises.

ENDNOTES

[1] Ümit Akcay, “Neoliberal Populism in Turkey and Its Crisis,” Institute for International Political Economy Berlin, Working Paper 100 (2018).

[2] Ümit Akcay and Ali Riza Güngen, “The Making of Turkey's 2018–2019 Economic Crisis,” Institute for International Political Economy Berlin, Working Paper 120 (2019).

[3] Esra Çeviker Gürakar, Politics of Favoritism in Public Procurement in Turkey: Reconfigurations of Dependency Networks in the AKP Era (Springer, 2016).

[4] Şahan Savaş Karataşlı and Sefika Kumral, "Capitalist Development in Hostile Conjunctures: War, Dispossession, and Class Formation in Turkey," Journal of Agrarian Change 19/3 (2019), pp. 528–549.

[5] Cihan Tuğal, The Fall of the Turkish Model: How the Arab Uprisings Brought Down Islamic Liberalism (New York: Verso, 2016).

Written by

This article was published in Issue 292-3.