We mourn the passing of the great Palestinian artist, Kamal Boullata, who died on August 6, 2019, and we offer our deepest sympathies to his wife and life-partner, Lily Farhoud, as well as to his family and friends. Kamal was a pioneer in the practice of contemporary Arabic art, renowned for evocative works across a variety of artistic mediums including paintings and silkscreens featuring geometric forms, and for his steadfast dedication to the people, history and rich culture of Palestine.

We mourn the passing of the great Palestinian artist, Kamal Boullata, who died on August 6, 2019, and we offer our deepest sympathies to his wife and life-partner, Lily Farhoud, as well as to his family and friends. Kamal was a pioneer in the practice of contemporary Arabic art, renowned for evocative works across a variety of artistic mediums including paintings and silkscreens featuring geometric forms, and for his steadfast dedication to the people, history and rich culture of Palestine.

Kamal was a dear friend and colleague, and closely associated with MERIP from its earliest days. We thought the most fitting tribute would be to gather recollections from several close friends who worked with Kamal on Middle East Report. Joe Stork, a founding editor, recalls Kamal’s contributions to the design of our publication. Salim Tamari, editor of the Jerusalem Quarterly and also a contributing editor of this magazine, provides a moving account of Kamal’s memorial service and burial in Jerusalem. Penny Johnson and Anita Vitullo, contributing editors of Middle East Report, who live in Ramallah and Jerusalem respectively, reflect on the impact of Kamal’s art on their lives. Joan Mandell and Lynne Barbee worked with Kamal closely when they were staff editors of the magazine and share their experiences of his art and his kindness. Vera Tamari, Ramallah-based artist, rounds out our circle with her essay on the consequence of exile on Kamal’s art and relationship with her brother, Vladimir.

Kamal came to Washington in 1968 to continue his art studies at the Corcoran Museum’s College of Art and Design, and was living there when we approached him about our vision. The very first issue of what was then MERIP Reports, in May 1971, bore the logo he designed, one that unmistakably and uniquely signified our magazine and larger project.

He contributed several more logos and mastheads for the magazine, including the one we use today. For many years he served as design editor of the magazine and was a member of Middle East Report’s editorial committee.

He contributed several more logos and mastheads for the magazine, including the one we use today. For many years he served as design editor of the magazine and was a member of Middle East Report’s editorial committee.

Around the same time that I left the magazine as editor, in 1996, Kamal and his wife Lily left Washington, initially to spend several years in Morocco on a Fulbright fellowship. They later lived in France, and most recently in Berlin. Along with several of the contributors below, I had the good fortune to spend precious time with Kamal and Lily in April 2018, when they visited Washington and Kamal delivered a dazzling talk at Georgetown University’s Center for Contemporary Arab Studies describing and illustrating the linkages and articulation of Arabesque design and calligraphy and the structures of Arabic grammar.

Around the same time that I left the magazine as editor, in 1996, Kamal and his wife Lily left Washington, initially to spend several years in Morocco on a Fulbright fellowship. They later lived in France, and most recently in Berlin. Along with several of the contributors below, I had the good fortune to spend precious time with Kamal and Lily in April 2018, when they visited Washington and Kamal delivered a dazzling talk at Georgetown University’s Center for Contemporary Arab Studies describing and illustrating the linkages and articulation of Arabesque design and calligraphy and the structures of Arabic grammar.

—Joe Stork

I first met Kamal in the late 1970s in Washington, DC where he stood out as an unusually focused, hardworking graphic artist, distinct from the rather lost Palestinian male exile community. My appreciation of him was fairly superficial at that time. (We once had a spirited argument over the hues of blue he chose for the design of a cover of a Journal of Palestine Studies.) I observed his searching nature, gentleness and strong sense of vision, but I did not know what it was that he saw and felt; I did not begin to understand him until after I moved to Jerusalem several years later.

His art seemed to me familiar and aesthetically beautiful, but it took me years in the “holy city” before I could begin to feel deeply—in a kind of unexamined parallel consciousness—how his color choices, slants of light, the insistent calligraphy, the drama and delicacy of his work, were his attempts to impart the beauty and pain of Jerusalem. As his work grew in complexity and sophistication, I now choose to see it as an uncommon challenge to the insidiously ugly and vicious occupation. Kamal was always reaching back in time, and forward into the future, to retrieve the city as his once again.

This was nowhere more poignant than at his funeral in the Old City. His last challenge was to be home again, where Greek Orthodox rituals took over, before several hundred family members, childhood friends and colleagues, in Jerusalem-pink light, to honor Kamal where he wanted to be honored: in an ancient cemetery high up in a quiet western corner of the old city. Salam, Kamal.

—Anita Vitullo

Kamal was one of our MERIP friends who I met when I worked on the staff in the 1970s. When we simplified the magazine’s name to Middle East Report, he designed our second logo (and later a third). Kamal introduced me to his world of politically sophisticated art and poetry. His gentle voice, constant smile and profound encouragement has reassured me through years of conversations and correspondence.

Kamal’s work was ubiquitous. Years later during a conversation with the proprietor of Jerusalem Pottery on the Via Dolorosa, I learned that the painted tiles with images of Jerusalem cityscapes were copied from drawings by a young Kamal. No artist credit was displayed, so that’s how I discovered that my friend had designed my kitchen tiles.

Kamal’s work was ubiquitous. Years later during a conversation with the proprietor of Jerusalem Pottery on the Via Dolorosa, I learned that the painted tiles with images of Jerusalem cityscapes were copied from drawings by a young Kamal. No artist credit was displayed, so that’s how I discovered that my friend had designed my kitchen tiles.

Kamal and Lily arrived in Jerusalem while I was working on my documentary, Gaza Ghetto. It was Kamal’s first visit in 20 years. He was persuaded to be the subject of another film, Stranger at Home, meant to challenge Israel’s “Law of Return” by which any Jew could move to Israel and become a citizen, while Palestinians, like Kamal, were stripped of residency rights in their birthplace. On that visit Kamal really just wanted to absorb all he could of his city, while introducing Lily to friends and family. He did not relish being at the center of a film, but hoped that his personal story would make a persuasive case for Palestinian rights.

In those days, it was possible to travel between the Palestinian areas with fewer constraints, so I was able to introduce Kamal to the family of Fathi Ghabin, a painter in Gaza imprisoned for six months by the Israeli military administration for the “crime” of featuring the colors of the Palestinian flag in a painting. Fathi was a Nakba survivor, living in Jabalia refugee camp in a modest home with a dirt floor just miles south of his home village of Hirbiya, where his people were no longer welcome. Kamal, a graduate of two prestigious art institutes who had exhibited internationally and earned commissions from wealthy patrons, was excited to meet Fathi’s family. From distinctively different experiences and life-styles, the artists shared painting as an ode to cultural identity and a means of resistance to dispossession and exile.

—Joan Mandell

It was the 1970s in Washington, DC. In the Dupont Circle-Adams Morgan-Mt. Pleasant neighborhoods we had a supportive community. I lived on S and 20th, Kamal and Lily lived on R. Kamal was welcoming and compassionate and we shared lots of tea, political frustrations, humor and joy.

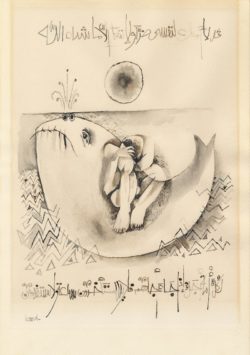

Kamal’s art then was openly Palestinian in subject matter. Exactly how I came to own two originals, I can’t remember. Later, while I was on the road as a union organizer for many years, my cousin lovingly guarded them on the walls of her office in New Jersey.

Kamal’s art then was openly Palestinian in subject matter. Exactly how I came to own two originals, I can’t remember. Later, while I was on the road as a union organizer for many years, my cousin lovingly guarded them on the walls of her office in New Jersey.

I eventually retrieved them (to her dismay) and Jonah hung prominently in my living room until I passed it to Lily and Kamal, after Lily informed me they didn’t have any of Kamal’s original early work. In my home, one of the first things I see when I wake is Kamal’s The Land. Lucky me.

—Lynne Barbee

Acafé in DC sometime as the 1970s turn into the 1980s. Kamal has just returned from Beirut, his eyes are sparkling. “Lily,” he says, “Lily.” Returning to a Beirut apartment for a lost sweater during his visit, he saw her on the balcony. Lily Farhoud would be his wife and partner for the rest of his life and he never lost the lilting, loving way he said her name.

It was Kamal’s voice that kept returning to me when the sudden, shocking news of his passing away in Berlin arrived A voice that was always surprised by the world around him, whether in wonder or indignation—wonder at its beautiful absurdities and indignation at its large and small horrors—the latter including a horror at art Kamal considered derivative. And I was indignant when “Oh My God” entered the global lexicon, for me it was Kamal’s signature expression.

Visiting Kamal and Lily in Berlin over the last several years, Kamal’s projects were all around him. He had returned to color and to large paintings in a surprisingly light-filled studio. Both Kamal and Lily found a home in Berlin, that city of strangers.

Kamal’s art has accompanied many of us from his line drawings inspired by Mahmoud Darwish’s poetry in the 1970s to his Gates of Jerusalem series to his calligraphic paintings—and so much more. Kamal was also a maker of remarkable books both for his own writing and, most generously, revealing the work of others such as the pioneering collection in 1978, Women of the Fertile Crescent: An Anthology of Modern Arab Poetry by Women. His most moving work for me was Faithful Witnesses: Palestinian Children Recreate Their World, where drawings and watercolors showed us how children saw their world of military occupation.

Kamal Boullata was himself a faithful witness: to the city of his birth, Jerusalem, to both his Palestinian compatriots and ancient Arab poets, and to the restless, beautiful, daunting world in which he and Lily wandered before he returned to his final resting place in Jerusalem.

—Penny Johnson

Imay have had only a small number of personal encounters with Kamal Boullata, but our deep acquaintance goes back to the early 1960s. Kamal and I were primarily connected through our engagement as artists, but more significantly through Kamal’s lifetime friendship and love for my late brother Vladimir, and what Kamal, in one of his letters, characterized as a friendship joined through “circumstantial chains connecting our destinies.” Their deaths on the same day, the sixth of August but two years and continents apart, was symbolic of their bond as artists, intellectuals and spiritual friends.

The years Vladimir and Kamal spent far from each other were much longer than all the time they spent close together in Jerusalem. In a memorial to their common Jerusalem friend Hani Jawhariyyeh, Vladimir wrote:

This friendship expanded to include, in our own words, the “four musketeers” of art in Arab Jerusalem of the late fifties and the years that followed: Hani (photography and cinema), Kamal Boullata and myself (art and painting) and Ibrahim Sous (piano and music composition).

That article was illustrated with portrait drawings of Hani by both Kamal and Vladimir, as well as a postcard drawing of a street in the Old City of Jerusalem by Kamal. Those were special times for those friends before the occupation of Jerusalem in the aftermath of the 1967 war. They owned Jerusalem.

During the walks that we took in those days in the streets of Jerusalem’s Old City and during family visits, a warm fraternal camaraderie grew between us the four young men. We joked and laughed as though we were trying to erase the atmosphere of defeat and disappointment around us…

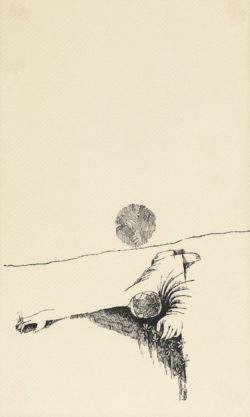

Kamal and Vladimir later spent a short period together in Beirut. In one of Vladimir’s sketchbooks of that period, one finds drawings by both of them, including a delicate ink and watercolor portrait of Kamal by Vladimir, while another of Vladimir himself executed in a more painterly style by Kamal but signed whimsically, “Vlalatta,” joining both their names in one signature.

Kamal by Vladimir

Vladimir by Kamal

For an exhibition of Palestinian art organized in Tokyo in August 2018, Kamal sent three works dedicated to Vladimir. Although the two had been separated over many decades filled with so many changes and challenges, they maintained a close and tender communication with one another, bonded by deep respect and a shared understanding of each other’s creativity, intelligence and genuine dedication to art. Above all they kept through their friendship a kindled love for Jerusalem, and a yearning for the city from which the two were forcibly exiled all their adult lives.

—Vera Tamari

Kamal Boullata was buried in the Orthodox Cemetery at Mt Zion on August 19. It took a miracle, and intensive efforts by his family and Jerusalem lawyers to convince the Israeli Ministry of Interior to allow the family to repatriate his body from Berlin to his birthplace. Around a thousand relatives, friends, diplomats and Jerusalemites from all walks of life, including his neighbors from the Old City, squeezed in the small Rum Orthodox Church at the foothill of the cemetery.

Kamal Boullata’s funeral in Jerusalem. Photo by Negotiations Affairs Department.

Many could not get in and waited in the outer garden for the services to finish. A few score came from neighboring towns, crossing the checkpoints in the sweltering heat to bid farewell to the prodigious artist. I travelled with my cousins Vera and Tania—who had continued to maintain contact with him since he left the country in the ‘60s. We could not stop being amazed at the timing of his death, coming as it did at the same day two years later of his childhood friend and fellow artist Vladimir Tamari. Both of them had made Jerusalem and its iconography the center of their art.

Although we all grew up in the Jerusalem area, we got lost on the way to the funeral in the new convoluted road system that separates Jerusalem from Ramallah. We made it to the church just as the Archbishop of Sebastia, Father Hanna Atallah, began his fiery sermon. “Kamal has come back,” he said, “over the bayonets, and barbed wires set up by the occupiers to block the sons and daughters of this country from being reunited with their homeland…. His dead body has arrived but his soul will live forever in his beloved Jerusalem.” Standing next to him were Muslim, Protestant, Melkite and Latin clerics—who seemed embarrassed by the nationalist oratory. Atallah has been the nemesis of both the Israelis and his own Greek Orthodox Patriarchate over issues of land transfers to Israeli settlers in Jaffa Gate.

The church was surrounded by old and archaic icons that Kamal wrote about in Palestinian Art: From 1850 to the Present, when he proposed his controversial thesis that modern Palestinian painting is rooted in Jerusalem iconography. At the door, a printed placard was placed by a Palestinian news agency, over a candle and a bowl of incense:

Kamal Boullata was born in Jerusalem in 1942 and grew up in the Old City. His family traces its history in the Old City for over 600 years, according to the records of the Orthodox Church of Jerusalem. For half a century, since 1967, he was barred from Jerusalem because he happened to be out of the country for an exhibit in Beirut in 1967 when the Israeli occupation started. All his efforts to return to Jerusalem failed, except for a brief visit in 1984 which was memorialized in the film “Stranger at Home.” However, Jerusalem always stayed in his heart and in his art.

As Kamal was laid to rest in the Boullata family compound, next to his grave by sheer coincidence was the resting place of George Antonious, on whose tombstone is engraved: أيها العرب انهضوا واستفيقوا (Arabs Everywhere, Wake Up and Arise!). How appropriate. Another priest was saying a final word, briefly this time, about the significance of being buried in Mt Zion:

This is the site of the last supper, the betrayal of Jesus by Judas Iscariot, and the vicinity of the Via Dolorosa, leading to the crucifixion of Christ and his resurrection. In the Muslim and Jewish traditions, the end of the days will happen at the slopes of the Mount of Olives, and God will hold his accounting of souls at Bab al-Rahmeh in the Eastern gates of the city. But for us this is the holy of holies.

In his lifetime, and in his earlier art, Kamal Boullata was militantly secular. In the later period, he became artistically engaged with religious culture. He was also mesmerized by religious motifs, and by Sufi spiritualism and Islamic calligraphy. I imagined him hearing these words in his claustrophobic box and smiling contently.

—Salim Tamari