Uncovering Protection Rackets through Leaktivism

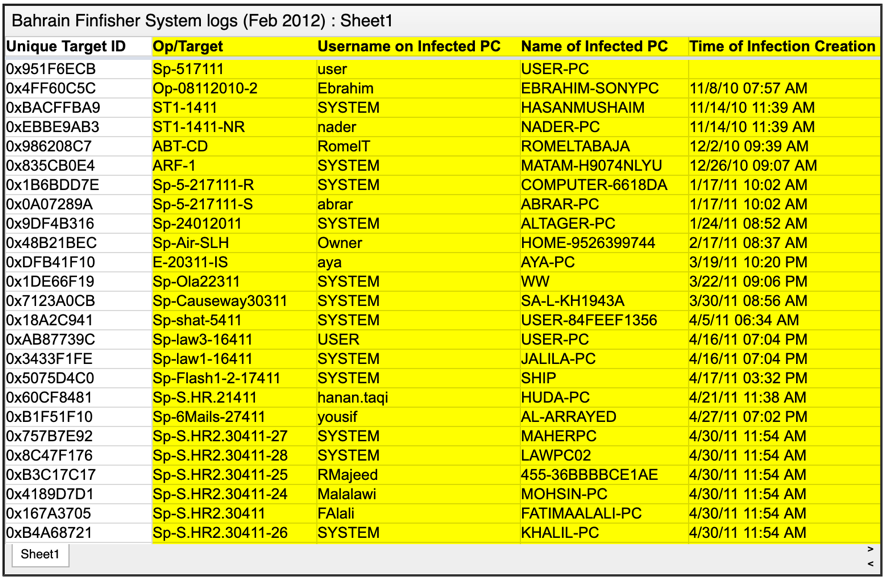

The small Gulf Arab state of Bahrain is using digital-era tools of surveillance, deception and repression to quell popular dissent. But a group of well-meaning tech-savvy geeks are mobilizing new digitally enhanced methods to expose who is behind this repression and how it operates today.