A close reading of a literary journal’s table of contents in colonized Palestine reveals a vibrant culture of resistance and renewal in the midst of destruction and dispossession.

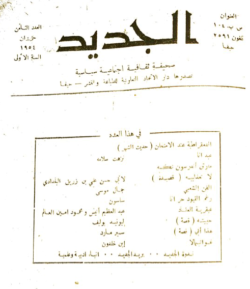

Table of contents of the literary journal al-Jadid: A Cultural, Social and Political Magazine, 2/1 (1954).

Democracy Tested (monthly editorial)

Am I a Slave?—Nazhat Salaama* (a poem)

Martin Anderson Nexo: Overview of his Life and Works

Do Not Slander Him—Abu Hassan Ali bin Zurayq al-Baghdadi (a poem)

‘Aqqad’s Genius—Abd al-‘Azim Anis and Mahmud Amin al-‘Alim

Popular Art—Jamal Musa

Despite the Chains I Am Free—Sasson Somekh (a poem)

Sweetheart—Leonid Soboleff (a story)

This is My Father—Samir Marid** (a story)

Guatemala—Ibn Khaldun***

Letter to the Editor .. al-Jadid Clubs .. Literary and Scientific News

*Reprinted from Falastin ** Pen name of Sami Michael ***Pen name of Emile Touma

What can a journal’s table of contents tell us about a particular literary culture? Quite a lot, it turns out, when one begins to excavate the political and cultural networks and practices of a period that are revealed therein.

A closer look at the table of contents of the Haifa-based, Arabic-language journal, al-Jadid (The New): A Cultural, Social and Political Magazine, first published in 1953, reveals an ongoing campaign to reconstruct an anti-colonial Arabic literary culture among Palestinians and some anti-Zionist Arab Jews inside Israel after the Nakba. The contents reveal a largely unknown network of literary correspondence among Arab, internationalist, communist and anti-colonial intellectuals and writers. It also reveals a wide variety of events and activities that encouraged the growth of local literature during the 1950s and early 1960s. [1]

Al-Jadid was the literary offspring of al-Ittihad (The Union), the newspaper of the Palestinian National Liberation League (NLL), founded in 1944. It was later transferred to the Israeli Communist Party (ICP), but kept its base in Haifa, a once Palestinian-majority city in the newly established Israeli state. Together the two periodicals laid the groundwork for a movement that eventually included many writers and other periodicals. Likewise, al-Jadid’s vision of narrating the lives of marginal and colonized communities in the early years of the state formed a collective story that explicitly refuted the premises of ethnocentric colonial Zionism and Arab-Jewish separation.

Like its parent-newspaper, al-Jadid was an anti-Zionist Communist publication founded soon after the advent of Israeli statehood and the 1948–49 Palestinian Nakba, which destroyed Palestinian society, decimating its political parties, cultural institutions, intellectual milieu and literary culture. Its mission was to rebuild this anti-colonial Arab literary landscape, or what in other colonial contexts has been described as a country’s “literary infrastructure.” [2] As in other colonized sites, Palestine’s literary infrastructure was devastated by violence and repression, and attempts at the formation of a national or collective movement necessitated new literary formations as well.

But in order to build a literary tradition, a country needs a publishing industry, gathering places, journals and the wide array of “institutions that provide literary training, facilitate and promote the circulation of literary texts, and consecrate literary value, including commercial, non-commercial and academic or state-supported cultural projects.” [3] A “literary infrastructure” requires more than the ability to publish books—it includes the supportive edifice that makes possible the development of writers, readers, literature, public literacy and literary culture to begin with.

Tracing the paper trails embedded in the journal’s table of contents provides an index—a textual mapping—of how al-Jadid organized itself around the daunting task of Arabic literary reconstruction after Nakba.

To begin with, al-Jadid’s founders utilized the form of the cultural journal. Many intellectuals in the colonized world created journals that became forums for oppositional politics, literary scenes and art practices. Low-cost, flexible publishing ventures like al-Jadid were able to nurture local culture through publishing new writers, transmitting debates, fostering intellectual networks and mentorship and exposing readers to local, regional and international work in translation. At the journal’s inaugural opening, the Palestinian writer and organizer Emile Habiby defined it as “the kernel and catalyst of a literary movement…a movement that begins with al-Jadid.” [4] Its goal was to develop multiple cultural fronts including popular education and literacy, writing, publishing, literary mentorship, poetry festivals and theater.

Next, tracing the journal’s table of contents provides a wide-ranging index of the different networks, affiliations and projects that sustained this development.

In the public section following the table of contents there are letters to the editor, cultural news and notes about institutional projects such as intellectual and literary clubs and writing or poetry festivals. These activities were part of a sustained cultural campaign to cultivate literary education, literary practice and a sense of political opposition and collective self-determination within the broader community. Clubs and festivals were also spaces where writers could establish networks and mentorships and lay people could discuss culture, literature and politics with like-minded individuals.

Above the public section are two other regular journal features. One is a work of local literature and literary criticism in the form of an article on the impact of Palestinian folkloric song on oppositional poetry by the Palestinian writer and organizer Jamal Musa. The other is a short story about the racial and colonial dynamics of Arab Jews living in transit camps situated on stolen Palestinian lands, by the Iraqi Jewish writer Samir Marid.

Moving further down the table of contents, literary scholars might notice a surprising, but critical item: the magazine’s reprint of the chapter “‘Abqariyyat al-‘Aqqad (The Genius of ‘Aqqad),” taken from the book Fi al-Thaqafa al-Misriyya (On Egyptian Culture), written by Marxist Egyptian intellectuals ‘Abd al-‘Azim Anis and Mahmud ‘Amin al-‘Alim, and prefaced by the important Iraqi Marxist literary critic and philosopher Husayn Muruwwa. [5]

The book was a manifesto for a new brand of politically committed literary practice and criticism, influenced by socialist realism and Sartre’s philosophy of literary engagement—a key text for the anti-colonial, socialist and Arab nationalist literary scenes of Cairo, Beirut and Baghdad. It was rooted in the rejection of the older nahdawi (enlightenment) generation of Arab literature—epitomized by thinkers such as Taha Husayn and ‘Abbas Mahmud al-‘Aqqad—and led by a new generation of Egyptian writers who rebelled against literary classicism, maintaining that literature must emerge from the base of society. [6]

It is not surprising to find this article reprinted in an Arab socialist literary magazine, but the fact that there was an embargo on all communications between Israel and the Arab world raises the question of how this reached the Haifa-based editors the same year it was published in Beirut? The most likely answer is that Emile Habiby procured Arab cultural magazines through his ties in the Communist party, allowing for the regular reprint of articles from major Arab periodicals such as Adab or al-Tariq. [7] Earlier in the table of contents, there is a poem by Nazhat Salaama reprinted from the Palestinian newspaper Falastin, relocated from Jerusalem to Amman after 1948. The poem further illustrates how through the journal writers and the public were able to overcome structural limitations and keep abreast of major trends in Arabic culture.

Finally, rounding out the table of contents are other articles that address the international socialist and anti-colonial cultural scene: a local poem by Sasson Somekh written in solidarity with African American musician and political organizer Paul Robeson; a review of the works of Martin Anderson Nexo, the Danish socialist writer; and a longer analysis of the popular struggle in Guatemala by the Palestinian historian Emile Tuma (pen name Ibn Khaldun). Such pieces were regular features in the journal, along with translated works by the likes of Federico Garcia Lorca, Nazim Hikmet and Langston Hughes. The journal was situated within a specific international network that funneled literary and cultural blueprints as well as translation of international literature into the local scene.

In 1968, the eminent Palestinian intellectual and writer Ghassan Kanafani published two volumes examining the impressive formation of an oppositional literary milieu amongst Palestinians inside Israel. He introduced the Arab world to its anti-colonial aesthetics and to the writers it supported such as Emile Habiby, Samih al-Qassem and Mahmoud Darwish. Kanafani also outlined the daunting barriers Palestinian writers confronted in this period. These barriers included the murder and exile of a generation of cultural critics and writers; the destruction of institutions, gathering places and ultimately entire cities as Arab intellectual hubs; the embargo between Israel and the Arab world, preventing access to Arabic literature in the major centers of knowledge and Israeli military censorship and limitations on movement, gathering and publishing. [8]

In sum, al-Jadid’s table of contents provides a rich paper trail for learning about this formidable effort to overcome obstacles and reconstruct cultural resistance under colonial rule. Histories of newspapers and journals are rarely examined by intellectual historians or literary scholars, who tend to focus on the canonical narratives that privilege individual writers and works above the political-cultural milieu that produced them. Yet in a period characterized by a renewed interest in the concept of decolonization, tracing these archives can provide scholars and activists with a rich portrait of anti-colonial literatures and counter-cultural institutions, as well as of local and global networks where they exchanged ideas and forged bonds of solidarity. ■

This MER article has been turned into an interactive teaching tool by Revolutionary Papers.

Endnotes

1 This connection has recently been examined in Maha Nassar, Brothers Apart: Palestinian Citizens of Israel and the Arab World (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2017).

2 For an in-depth discussion of literary infrastructure see Katerina Gonzalez Seligmann, “The Void, the Distance, Elsewhere: Literary Infrastructure and Empire in the Caribbean,” Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism, Forthcoming.

3 Ibid.

4 Emile Habiby, “Humanity is the Aim of Literature and its Subject,” al-Jadid 1/3 (1954). [Arabic]

5 Mahmud Amin al-‘Alim and ‘Abd al-‘Azim Anis, On Egyptian Culture (Beirut: Dar al-Thaqafa al-Jadida, 1989). [Arabic]

6 See Samah Selim, “The Politics of Reality” in The Novel and the Rural Imaginary in Egypt (London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2004) and Yoav Di-Capua, “Commitment,” in No Exit. Arab Existentialism, Jean-Paul Sartre and Decolonization (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018).

7 See Sayf al-Din Abu Salih, The Arabic Literary Movement in Israel, Volume II (Haifa: The Arabic Language Academy, 2010), p. 361. [Arabic]

8 Ghassan Kanafani, Literature of the Resistance in Occupied Palestine (Cyprus: Rimal Books, 2015), pp. 14–15. [Arabic]