The UN Secretary General’s personal envoy to Western Sahara, Horst Koehler, invited the main parties to the conflict to a round-table meeting in Geneva on December 5-6, 2018. The two claimants to the territory, Morocco and the Polisario Front, sent delegations. In addition, and as at previous talks, neighbouring Algeria and Mauritania were also invited to attend.

These talks were the first face-to-face meetings since 2012 when the previous round of negotiations dissipated into years of fruitless shuttle diplomacy. UN peacekeepers have been on the ground in Western Sahara for nearly three decades as part of the mandate of MINURSO (United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara), which has been renewed regularly since 1991 even though the Secretariat’s negotiators have made little progress toward a solution to the Morocco-Sahrawi dispute.

Several developments in the past two years, including the Trump Administration’s antagonism towards what it terms the “business as usual” of the UN peacekeeping mission, have sparked some interest in the United Nations to tie the fate of MINURSO in Western Sahara to progress at the negotiating table as a way to break the political stalemate. Nevertheless, the forces protecting the status quo, and thus Morocco’s ongoing colonization of Western Sahara, remain durable, and it is unclear whether this new round of talks will presage a broader resolution to one of the oft-forgotten conflicts of our times.

Stability Over Self-Determination

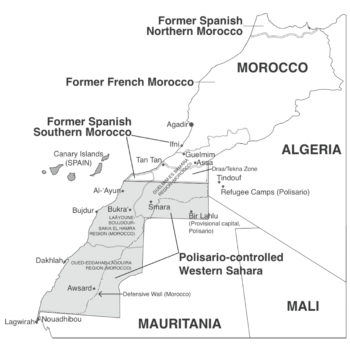

The origins of the conflict can be traced to Morocco’s invasion of Western Sahara in 1975 as Spain withdrew from Spanish Sahara, the colony it had acquired in 1885. The United Nations, and the 1975 Advisory Opinion of the International Court of Justice, were putting pressure on Spain to organize a referendum on self-determination for the native Sahrawi people. Facing a Moroccan military invasion of its desert colony and with the dictator Franco on his deathbed in October 1975, Spain abandoned its plans for a plebiscite and arranged for Morocco and Mauritania to divide the territory. Mauritania renounced its claim in 1979 and later recognized the government for Western Sahara which the pro-independence Polisario Front founded in 1976, the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR). War between Morocco, supported by France and the United States, and the Polisario Front, backed by Algeria, lasted until a ceasefire was established in 1991, which still holds today.

The eventual status of Western Sahara, and wider question of the role and influence of Morocco in North Africa and the Sahara, are of interest to both Algeria and Mauritania for obvious reasons of territorial security and its rich trove of resources. Algeria not only hosts the exiled SADR government, but also the thousands of Western Saharans who were exiled by Morocco’s invasion in 1975 and who now number 173,000.

United Nations peacekeepers arrived in 1991 under the mandate of MINURSO to help organize a vote on independence. Morocco assumed it could win the vote by manipulating the electorate through the attempted inclusion of tens of thousands of Moroccan citizens with no ethnic, historical or territorial ties to Western Sahara. The provisional voter list of 2000, however, hewed closely to the last Spanish census and thus would have likely led to independence. Around that time, the new King of Morocco, Mohammed VI, began to reject any solution that could lead to independence, which put Morocco’s position at odds with UN Security Council mandates and international law.

Morocco nonetheless formally proposed granting the territory autonomy, under Moroccan sovereignty, in 2007, and has insisted since then that its proposal should form the basis of any negotiations with Polisario. Polisario has been willing to discuss autonomy, but only in the context of a political process where independence (i.e., self-determination) is still an option, hence the political stalemate.

In the world after the September 11 attacks, the North Atlantic community, led by Paris and Washington, began to view the stability provided by the UN mission in Western Sahara as an end in itself. Since at least 2004, the Council—unable to take independence off the table (because of international law) yet unwilling to force Morocco to contemplate it (because of geopolitics)—has opted to keep the parties talking in the hopes that a new reality will someday emerge.

Managing the Protracted Stalemate

The Geneva talks in December are the first between Polisario Front and Morocco in six years. But the peace process has been stalemated for much longer than that. Since the beginning of the UN-brokered armistice between Morocco and the Polisario Front in 1991, MINURSO has monitored the cease-fire but has been unable to come close to holding the referendum whose name the mission bears. Peace plans developed by James Baker in 1997 and 2003 were rejected by Morocco and ultimately deemed unenforceable by the Security Council, leading to Baker’s resignation in 2004.[1]

Baker’s two successors have been just as unsuccessful in their efforts to reach a political solution. The most recent UN envoy, Christopher Ross, a former US ambassador to Algeria and Syria, resigned in March 2017 after eight years on the job. Though Algeria and Polisario had always expressed confidence in his abilities, the Moroccan government grew increasingly frustrated that Ross did not premise negotiations on Rabat’s 2007 autonomy proposal for Western Sahara. The last five years of Ross’s tenure saw increasingly futile shuttle negotiations as Morocco refused to negotiate. What little pressure the Obama administration had been willing to put on Morocco was limited to raising questions about Rabat’s human rights practices in the occupied territory. In late 2010, Western Sahara witnessed the largest pro-independence demonstrations in the history of the conflict, which were brutally repressed by Morocco’s security forces.[2]

If formal talks have been sporadic and often lacked clear outcomes, the parties have been pursuing other initiatives in the past few years. Polisario has achieved favorable outcomes in legal cases calling into question Morocco’s exploitation of resources from a non self-governing territory.[3] Morocco is focused on increasing its reach and influence in Saharan and sub-Saharan Africa. In January 2017 the Kingdom rejoined the Africa Union, which it had left in protest at the admission of SADR in 1984.

Last month’s meetings in Geneva are also the first talks since then UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon rocked the boat in March 2016 by referring to Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara as an “occupied” territory; Morocco retaliated by requesting the UN to withdraw staff members and to close a military liaison office for Minurso. Recent years have also seen heightened military tensions between Morocco and Polisario along Morocco’s 1,700 mile defensive wall, or sand berm, that bisects the territory.

A series of developments since 2017, however, have shaken up several elements of the gridlocked management of the conflict, leading to renewed movement and eventually the Geneva talks.

The Trump administration, led by ambassador Nikki Haley, seemed to suggest in 2017 that MINURSO could no longer exist in perpetuity as a peacekeeping mission without also demonstrating progress toward a political solution. This brought a new sense of urgency to the talks, as both sides would have much to lose and little to gain from MINURSO’s withdrawal. Horst Köhler, the former president of Germany, was soon announced as Ross’s replacement in the months that followed.

Finally, in April 2018, the UNSC renewed MINUSRO’s mandate, but only for six months. It was renewed again in November 2018 once Köhler had secured commitments to a new round of talks. As the US representative to the United Nations warned back in April, “there can be no more business as usual”. Behind the scenes, it appeared that the US delegation had also broken with the traditional consultative process in the drafting of the resolution. Since the mid-1990s, the United States had always taken the lead in drafting MINURSO resolutions, but always in close cooperation with France, the United Kingdom, Russia, and Spain (the so-called Friends of Western Sahara) before it was presented to the other members of the Council for consideration.

While this consensus-based process has been part of the dynamic reinforcing a status quo that has provided international political cover for Morocco’s ongoing colonization and economic exploitation of Western Sahara, it has rarely been met with anything short of a unanimous vote from the entire Security Council and especially the Permanent Five. In breaking with this tradition, the US resolution elicited almost unprecedented abstentions from two permanent members of the Security Council with little historical interest in the Western Sahara issue, China and Russia, as well as the de facto AU representative on the Council, Ethiopia, a state that also recognizes SADR.

An End to Business as Usual?

The Geneva talks ended in an agreement to reconvene for similar meetings in the first quarter of 2019. Since the 1980s, the parties have met for face to face talks before, and it is too early to say whether “business as usual” has ended. Operating under Chapter VI of the UN charter, the only material leverage the Security Council has in Western Sahara is to tie the fate of MINURSO’s peacekeeping force to progress at the negotiating table. The Council, however, has always been loath to terminate a mission that appears to be keeping the peace in Western Sahara. In past few years, several nearby countries—Mali, Chad, Niger, Libya, and Nigeria—have witnessed increasing levels of terrorism and armed conflict which have raised international concerns about the possible destabilizing effects of a UN withdrawal from Western Sahara.

The consternation surrounding the April 2018 resolution suggests that the key players on the Council are uncomfortable with this new direction, including those that voted “yes.” Following the April 2018 vote, France’s UN representative expressed hope that the shorter mandate was an “exception,” not the new norm. On the other hand, the new UN Secretary-General António Guterres ordered an unprecedented internal audit of MINUSRO earlier this year, another fact that is suggestive of widespread disillusionment with the mission’s lack of bearings in the United Nations.

While there are questions about whether or not Haley’s replacement, and the embattled Trump administration more generally, will stay the course or revert to the historical norm in Western Sahara (i.e., a consensus-based approach that has effectively decoupled peacemaking and peacekeeping), the new US attitude toward Western Sahara appears to be driven by John Bolton, who became Trump’s National Security Advisor shortly before the April vote on MINURSO. Bolton has a long history with the Western Sahara conflict, from his days in heading the State Department’s UN office at the end of the Cold War, to serving as an aide to Baker’s Western Sahara mission in the late 1990s, to his controversial interim appointment as the US representative to the United Nations from 2005 to 2006. It is no secret that Bolton has been sympathetic toward Polisario, a cause that became popular among the UN-bashing conservatives in the mid-1990s. While Bolton’s “get tough” approach to Western Sahara might be framed in terms of sensible UN cost-cutting, his recent statements on the issue, where he framed the Western Sahara question as a simple matter of organizing a vote on independence, have sent the Moroccan diplomatic corps, Washington D.C. lobbyists and media apparatus into a frenzy.

In every game of chicken the Council has played with either Morocco or the Polisario Front, however, the Council has always lost. Casualties of this brinksmanship have included all prior UN envoys: Köhler is now the fourth to take on this task. There has been no fundamental change to the basic geopolitical architecture of the conflict to suggest that Morocco and Polisario Front are more willing to accept an outcome they view as existential annihilation (respectively, independence for Western Sahara or some kind of political-economic integration with Morocco). Nor is there any indication that the Security Council is willing to impose a solution, or even a pre-determined process, on the parties. While the US can easily veto MINURSO, a peaceful and internationally acceptable solution to the Western Sahara dispute would nonetheless require a MINURSO-like entity to help organize the territory’s right of self-determination, to help repatriate the refugees from Algeria and to help maintain security during the transition from Moroccan rule to either autonomy or independence.

Moreover, many of the wider conditions which perpetuate the conflict and its grievances are very much still in place and show no signs of weakening. International law—and UNSC resolutions—still underscore the right of the people of Western Sahara to self-determination, as do several recent court decisions in the European Union and South Africa. The UN recognizes Polisario Front as sole representative of the people of Western Sahara.

Meanwhile, the Sahrawi nationalist movement benefits from a safe haven in Algeria, which serves as a base for pro-independence Sahrawi activism. Recent years have seen this activism flourishing beyond the refugee camps in Algeria: in Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara, in the Sahrawi diaspora, and in social media campaigns. The “supply” side of Sahrawi nationalist demand for self-determination seems assured.

Though the recent and sudden improvement in relations between Eritrea and Ethiopia might give hopes for a similar thaw in relations between Algiers and Rabat, perennial hopes for a change in direction vis-à-vis the question of Western Sahara remain wishful thinking. The fact that Algeria and Morocco survived the Arab Spring relatively unscathed is suggestive of the extent to which both states have developed robust mechanisms for the reproduction of their regimes. As the generation of leaders who knew a world before the Western Sahara conflict fades away, those able to imagine another reality beyond the status quo seem to be disappearing as well.

For its part, Morocco continues to reap significant economic benefits from its social and infrastructural colonization of Western Sahara. Whether or not the costs of Morocco’s ongoing investments in a territory rich in phosphates and fishing stocks can meet the expenses of its military and surveillance presence there, the decades-long effort to annex Western Sahara still reaps sizeable ideological dividends for the Moroccan regime in the form of a never-ending nationalist campaign to “reclaim” the “Moroccan Sahara” from Spanish imperialism and to protect it against Algerian machinations. Losing the territory would question the very legitimacy of the King’s rule and the socio-political order the monarchy has constructed out of the 1975 conquest. For many Moroccans the idea of losing Western Sahara to Polisario is as unthinkable as the notion of the Kingdom becoming a republic.

As a key ally for the US and the EU in agendas for regional security in the Sahara-Sahel and as a chokepoint for immigration from sub-Saharan Africa to Europe, Morocco can confidently expect its allies’ support for securing the conditions of ongoing rule and stability. These conditions still include facilitating Morocco’s presence in and exploitation of Western Sahara.

Above all, France has supported Moroccan efforts to decouple MINUSRSO’s primary and secondary functions. Though MINURSO ostensibly exists to facilitate a political solution that respects Western Sahara’s right of self-determination, its secondary peacekeeping function has effectively provided international cover for Morocco’s ongoing colonization of the territory since 1991.

An Enduring Crisis

Just as the geopolitical realities behind the conflict remain largely unchanged, so too do the realities on the ground for Sahrawis living under Moroccan occupation or in exile in Algeria. Sahrawi activists contesting Moroccan rule continue to provide substantive documentation, now easily circulated by social media, that the Moroccan authorities commit human rights abuses against nationalist Sahrawis.[4] Troublingly, MINURSO is one a few UN peacekeeping missions in the world whose mandate does not include a provision for human rights monitoring, due in large part to French protection on the Security Council. Similarly, some Sahrawis in the Moroccan-controlled territory continue to voice grievances that the economic investment and development of the territory under the auspices of Morocco does not benefit the Sahrawi population but instead go to Moroccan settlers, corporations, and political-economic oligarchs of the makhzan. Sahrawis living under occupation are widely believed to have become a minority compared to the Moroccan settler population, which has expanded greatly under the political cover provided by the ongoing UN mission.

Meanwhile, the community of Sahrawi refugees in Algeria, who began to organize their own refugee camps and aid delivery systems in 1976, continues to live in existentially and materially precarious circumstances in exile.[5] Malnutrition, unemployment, poverty, a harsh climate, limited access to clean water and a sense of abandonment by the world’s power-holders continue to make life hard for many refugee families. When the UN mission arrived in 1991, there was already an upcoming generation of Sahrawi exiles who had known nothing but life in the camps. Today, eighteen years after MINURSO produced the list of voters for an ever-postponed referendum, there is a new generation of Sahrawis who have never known a world in which they did not feel betrayed by the United Nations.

Endnotes

[1] Jacob Mundy, “Stubborn Stalemate in Western Sahara,” Middle East Report Online, June 26, 2004.

[2] Jacob Mundy, “Western Sahara’s 48 Hours of Rage,” Middle East Report 257 (Winter, 2010).

[3] Court of Justice of the European Union, Press release No 21/18, Judgment in Case C-266/16, Luxembourg (February 27, 2018); High Court of South Africa, Case No. 1487/2017, Port Elizabeth (February 23, 2018).

[4] Amnesty International, Amnesty International Report 2018/18: The State of the World’s Human Rights, London (2018).

[5] Alice Wilson, “North Africa’s Invisible Refugees,” Middle East Report 278 (Spring, 2016).