On March 6, 2017, hundreds of local residents took to the streets of towns and cities in Upper Egypt and the Nile Delta after the Ministry of Supply cut their daily ration of subsidized baladi bread. By the following day, thousands were protesting in 17 districts across the country. In Alexandria, protestors blockaded a main road at the entrance of a major port for over four hours, while residents in the working class Giza suburb of Imbaba blocked the airport road. Elsewhere, women in the Nile Delta city of Dissuq staged a noisy sit-in on the tracks of the local train station, where they chanted, “One, two, where is the bread?” and called for the overthrow of President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi’s government. [1] It was not long before the Arabic hashtag #Supply_Intifada was trending on Egyptian Twitter. In a bid to curtail further mobilization, Egypt’s military-backed government scrambled to restore residents’ access to bread, and promised to increase the ration in areas that had seen protest.

Food ProtestsEgypt’s latest round of food protests comes amidst ongoing price shocks resulting from the flotation of the Egyptian pound in November 2016. The devaluation of the pound is part of a series of measures, which include spending cuts and the introduction of a value added tax, demanded by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in exchange for a 12 billion dollar loan to prop up Egypt’s failing economy. [2] By February 2017, food inflation reached 42 percent. [3] Key staple goods have been particularly affected: Over the past year, Egyptians have seen the cost of bread and cooking oil go up by nearly 60 percent. [4] To put this into perspective, in the year leading up to the 2011 Arab Spring, food prices in Egypt were subject to an annual increase of around 15 percent. [5] Citing these and comparable developments, scholars have argued that grievances arising from food insecurity were a key factor in the outbreak of the 25th January Egyptian Revolution. [6]

There is historical precedent here. In Egypt, the price of bread has been seen as a potentially explosive issue since the 1977 “Bread Intifada”—when then President Anwar Sadat’s pledge to end subsidies on several basic foodstuffs sparked unruly protests across the country, which were met with harsh repression. Within two days, the state had reversed course, pledging to leave the subsidy system intact. Elsewhere in the region, attempts to cut state subsidies have suffered a similar fate: In recent years, austerity measures have been thwarted by street-level mobilization in Morocco, Tunisia, Jordan, Yemen and Mauritania. [7] Fast forward to 2017 and the contours of future contestation in Egypt may now be taking shape, as soaring inflation is coupled with high levels of unemployment. [8] Indeed, if grievance led explanations for the timing of the 2011 Arab Spring are correct, then the scope conditions for another mass uprising are seemingly in place.

Viewed against this backdrop, a close examination of the recent food protests in Egypt can provide new insights into the unfolding dynamics of contentious politics in the country, and in particular, the depths of the military-backed government’s resolve to implement further IMF-mandated reforms and how it will react to renewed street level mobilization if the economic situation continues to deteriorate. To conduct our analysis, we compiled an event catalogue of recent food protests in Egypt from Arabic language news reports and videos of protests uploaded to social media. Information was recorded for a protest’s location, the number of participants, protestors’ tactics, whether the protest was repressed by Egyptian security forces, and any novel performances or chants. In total, we identified 24 food protests occurring between March 6 and 7, 2017, in 17 districts across five governorates.

Supply IntifadaThe different ways that Egyptians gain access to the subsidy system is key to understanding the patterning of recent food protests. Subsidized bread costs five piasters a loaf. Following the recent surge in food prices, this is up to ten times cheaper than the cost of an unsubsidized loaf sold on the open market. Like other state subsidized foodstuffs, subsidized bread can only be purchased from outlets registered with the Ministry of Supply. While some of these are run as cooperatives, most operate as private businesses. Since 2014, the purchase of subsidized goods has been nominally regulated through the use of a smart card system, implemented as part of the government’s ongoing austerity program. This system allows smart card holders who do not claim their allocation of bread to receive credits, which can be used to buy other subsidized goods. However, distribution of individual smart cards has been partial. In the 2016-2017 budget, the Ministry of Finance planned for 82 million Egyptians (92 percent of the population) to claim the bread subsidy. [9] But according to the most recent figures published by the Ministry of Supply, only 69 million Egyptians have access to smart cards, leaving 13 million Egyptians (16 percent) reliant on paper cards to receive their subsidy. [10] As a stopgap, the Ministry of Supply has issued merchants with “gold cards.” In this parallel system, merchants are allocated a daily quota of 1,000-4,000 loaves of bread, depending on the number of paper card holders in their area. Every time a merchant sells an amount of subsidized bread to a customer with one of the old paper cards, they are supposed to record the sale by swiping their gold card which is, in turn, deducted from their daily quota. This process is coordinated at the subdistrict level by local Supply Offices. [11]

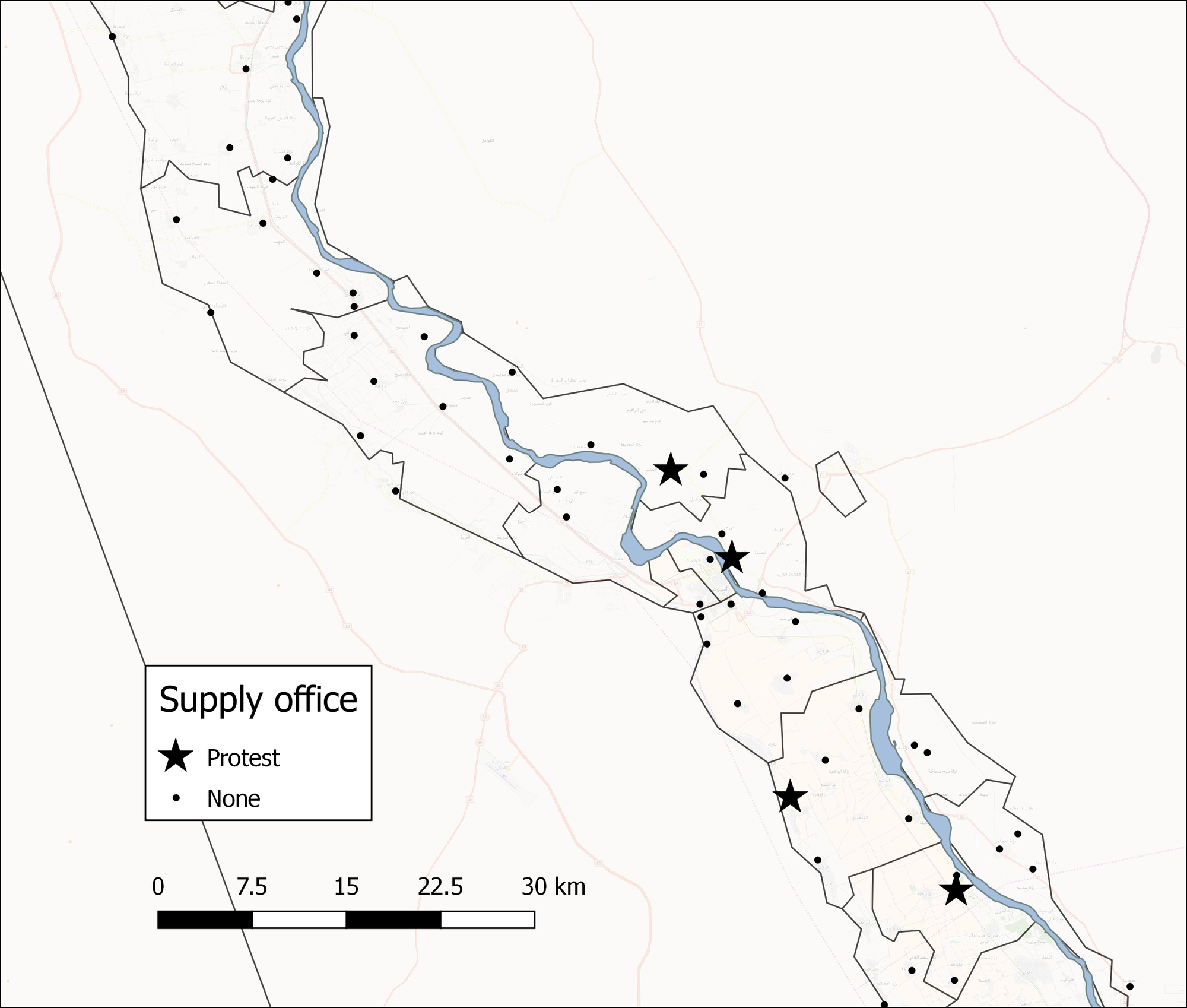

Figure 1. Food protests outside Supply Offices in Asyut, March 6, 2017.

On March 6, the Ministry of Supply announced that the daily bread quota available on gold cards was to be slashed to just 500 loaves. Unable to meet demand, state registered bakeries across the country cut the daily ration of bread available to paper card holders from five to three loaves, provoking demonstrations outside Supply Offices in several districts. To give an illustration: In Asyut, one of Egypt’s poorest governorates, there are over 870,000 subsidy smart cards in circulation, to support 3.2 million individuals (75 percent of the population). [12] This leaves a significant number of residents reliant on the old paper card system. Subsidized foodstuffs are available for purchase at over a thousand registered outlets, which are in turn overseen by 65 Supply Offices. In response to the cut in the gold card quota, impromptu protests by paper card holders were held out outside of Supply Offices in the districts of Abnub, Abu Tig, al-Fath, and Sidfa (see Figure 1).

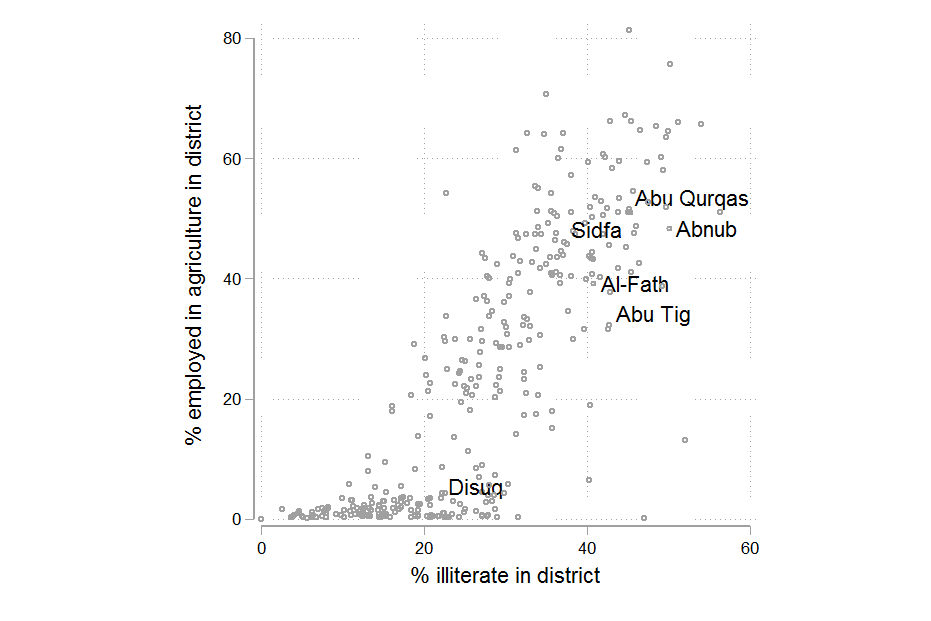

On the same afternoon, protestors mobilized outside of the Supply Office in Abu Qurqas in the neighbouring governorate of Minya. [13] Meanwhile, several hundred kilometers to the north in the Nile Delta city of Dissuq in Kafr al-Shaykh, protestors blocked the main road outside of the city council building, calling for the quota to be reinstated. Though disparately located, these offices share some common characteristics: Measured in terms of the illiteracy rate (a proxy for deprivation) and the extent of the agrarian economy, they service some of the poorest and—with the exception of Dissuq—the most rural districts in Egypt (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. How food protests on March 6, 2017 varied by illiteracy and employment in agriculture.

The following day, with local residents continuing to mobilize in Asyut, Kafr al-Shaykh, and Minya, the protests spread to more urban areas. In Alexandria, several hundred residents mobilized outside of the Supply Offices in al-Dukhaylah and al-Manshiyah, while large crowds blocked main roads and tram lines in Asafra, al-'Atarin, and al-'Amriyah chanting, “We want bread” and “You take my sustenance, you’re trying to kill me.” In Giza, local residents in al-Warraq and Imbaba also blockaded the entrances of their local Supply Office demanding that the full ration of bread be reinstated. Meanwhile, new protests broke out in previously quiet districts located in the governorates of Asyut, Minya, and South Sinai. In all of these cases, it seems that local residents followed a repertoire that predates the model of mobilization pioneered during the 25th January uprising. [14] Rather than trying to occupy squares and politically symbolic urban spaces, protestors acted locally to where they lived, inflicting an immediate cost on the authorities by impeding the flow of traffic and disrupting the functioning of local government.

The Regime RespondsSince the 2013 coup that ousted Islamist president Muhammad Mursi, the military-backed government has used a draconian anti-protest law to detain thousands of protestors. It is striking then that of the 24 food protests that we were able to identify, only four were met with any kind of repression. All the events that were repressed took place in the major urban centers of Alexandria and Giza, and it seems that only minimal force was employed. In the most serious episode in al-Warraq in Giza, police forces eventually dispersed protestors blockading the local Supply Office, arresting several in the process. The police also broke up the food protest in Imbaba after residents moved to blockade the airport road. However, these were exceptions to the general pattern. In Dissuq, where some the first food protests broke out, the head of the city council met with the protestors in an attempt to persuade them to end their blockade. [15] When they refused, the governor was telephoned, who in turn pledged to lobby the Minister of Supply to reinstate the quota. Later the following evening, it was announced that the gold card quota in bakeries in Kafr al-Shaykh had been increased, prompting the protestors to demobilize. [16]

So too, in Alexandria, police forces looked on as local residents blocked the tram line in several districts. In Asafra, instead of clearing the sit-in, police officers initially reassured the protestors that the decision to cut the quota would be reversed, although it was later reported that riot police had been deployed to secure the area. [17] That afternoon, police officers were photographed touring working class areas in Alexandria distributing bread to residents. [18] Elsewhere, protestors involved in small scale blockades of local supply offices were left to continue their sit-ins with only minimal interference from security forces.

By the evening of March 7, Egyptian state media reported that the Minister of Supply had issued an apology and reaffirmed that “Every citizen has a right to subsidized bread.” [19] The next day, the Ministry of Supply rushed to distribute 100,000 new smart cards in six governorates to replace existing paper cards, including in four of the five governorates that had played host to food protests. It also increased the gold card bread quota in four governorates, three of which had witnessed protests. [20] In a bid to deflect criticism for the cuts, the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Supply announced that they would launch a campaign of inspections on state-registered bakeries, to crack down on corruption. [21] Meanwhile, fearful that the protests may scale up again following Friday prayer, the Ministry of Endowments issued a sermon that called on Egyptians to reflect upon the country’s tightened economic circumstances and to be prepared to make sacrifices for the homeland. [22] This was followed by President Sisi himself making a public statement, pledging that the bread quota would not be cut again. [23]

On the BreadlineWhat can we learn from this episode? In many ways, the Supply Intifada underlines the continuing potential for government policies in Egypt to be generative of protest. Here, the decision to cut the quota available on gold cards was greeted almost immediately by disruptive mobilization. At the same time, the trajectory of the mobilization suggests that economic grievances alone do not predict the scale of protest. Between March 6 and 7, millions of Egyptians faced an immediate threat to their food security—but only a small minority of those affected took to the streets in what were highly localized protests. Still, the contexts of the first food protests are revealing. There is a commonly received wisdom in policy circles (especially those of international financial institutions) that the urban middle classes are more likely to mobilize in response to cuts to their subsidies. [24] It is notable that the system to reward smart card holders for not claiming their bread subsidy disproportionately benefits middle class families, who are more likely to consume staple foods other than bread (such as rice) or purchase higher quality unsubsidized bread. Tellingly, the cut to the gold card bread quota was coupled with a planned increase in the amount of credit that smart card holders would receive. [25] But as the March protests clearly show, the poor, both rural and urban, are also willing and able to mobilize against subsidy cuts. The class dynamics of bread subsidies seem not to have been lost on Egypt’s poor, either. In Alexandria, women protestors chanted, “They eat fino [higher quality] bread, and we can’t find our bread.” Several protestors interviewed by the media complained about the quality of subsidized baladi bread, with one woman commenting that it should be used as chicken feed. “Would the Minister of Supply eat this?” she asked the camera, as a group of children jostling around her yelled out “No!” in unison. The regime’s behavior in the face of these disruptive protests shows that not only were the authorities unprepared for this backlash, but that the regime fears provoking this constituency further, manifest in the Minister of Supply’s immediate volte-face and the police’s reluctance to crack down on residents. Even small localized protests, this suggests, can be an effective tool for extracting concessions from Sisi’s regime.

Endnotes

[1] See video footage: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RCR5WCjmFAQ; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6gQSkCqCJo4.

[2] International Monetary Fund, "Key Questions on Egypt," February, 16 2017.

[3] Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS), March 9, 2017.

[4] Ibid.

[5] CAPMAS, "Monthly Bulletin of Consumer Price Index: December 2010." [Arabic]

[6] Jeroen Gunning and Ilan Baron, Why Occupy a Square? People, Protests and Movements in the Egyptian Revolution (London: Hurst, 2013).

[7] Laura El-Katiri and Bassam Fattouh, “A Brief Political Economy of Energy Subsidies in the Middle East and North Africa,” Oxford Institute for Energy Studies Working Paper Series, MEP-11 (2015); Carlo Sdralevich et al., Subsidy reform in the Middle East and North Africa: Recent progress and challenges ahead (International Monetary Fund, 2014).

[8] CAPMAS, "Monthly Bulletin of Consumer Price Index: January 2017."; CAPMAS, "Monthly Bulletin of Consumper Price Index: November 2016." [Arabic]

[9] Ministry of Finance, "Financial Statement 2016-2017," May 2016. [Arabic]

[10] Ministry of Supply, January 2016.

[11] For a list of merchants and Supply Offices, see: http://subsidy.egypt.gov.eg/CardCitizens/Login. [Arabic]

[12] Ministry of Supply, January 2016.

[13]For video footage of interviews with local residents see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y5Ii3tAwtIs

[14] See Neil Ketchley, Egypt in a Time of Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

[15] Al-Masry al-Youm, March 7, 2017.

[16] Al-Masry al-Youm, March 8, 2017.

[17] Mada Masr, March 7, 2017; Masr al-Arabia, March 7, 2017.

[18] Al-Ahram, March 7, 2017.

[19] Al-Ahram, March 7, 2017.

[20] Ministry of Supply, March 8, 2017.

[21] Al-Watan, March 8, 2017.

[22] Ministry of Endowments, March 8, 2017: http://ar.awkafonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/1438-06-02.pdf

[23] Daily News Egypt, March 14, 2017.

[24] See for example, Sdralevich et al., Subsidy reform in the Middle East and North Africa: Recent progress and challenges ahead (International Monetary Fund, 2014) and Paolo Verme, “Subsidy reforms in the Middle East and North Africa Region: a review,” Policy Research Working Paper 7754, World Bank, 2016.

[25] Al-Shorouk, February 26, 2017.

Figure credits: Neil Ketchley and Thoraya El-Rayyes, from CAPMAS data.

Written by