Hardwiring Normalization—Infrastructures, Extraction and Gaza’s Future

In the summer of 2025, a 38-page blueprint circulating inside the Trump administration was leaked to the press: the Gaza Reconstitution, Economic Acceleration and Transformation (GREAT) Trust.

At first glance, it resembled countless other speculative development schemes, renderings of luxury resorts, free-trade zones and smart cities. Gaza, the plan insisted, could be remade as part of an “Abrahamic fabric” and a new “pro-American regional architecture.”

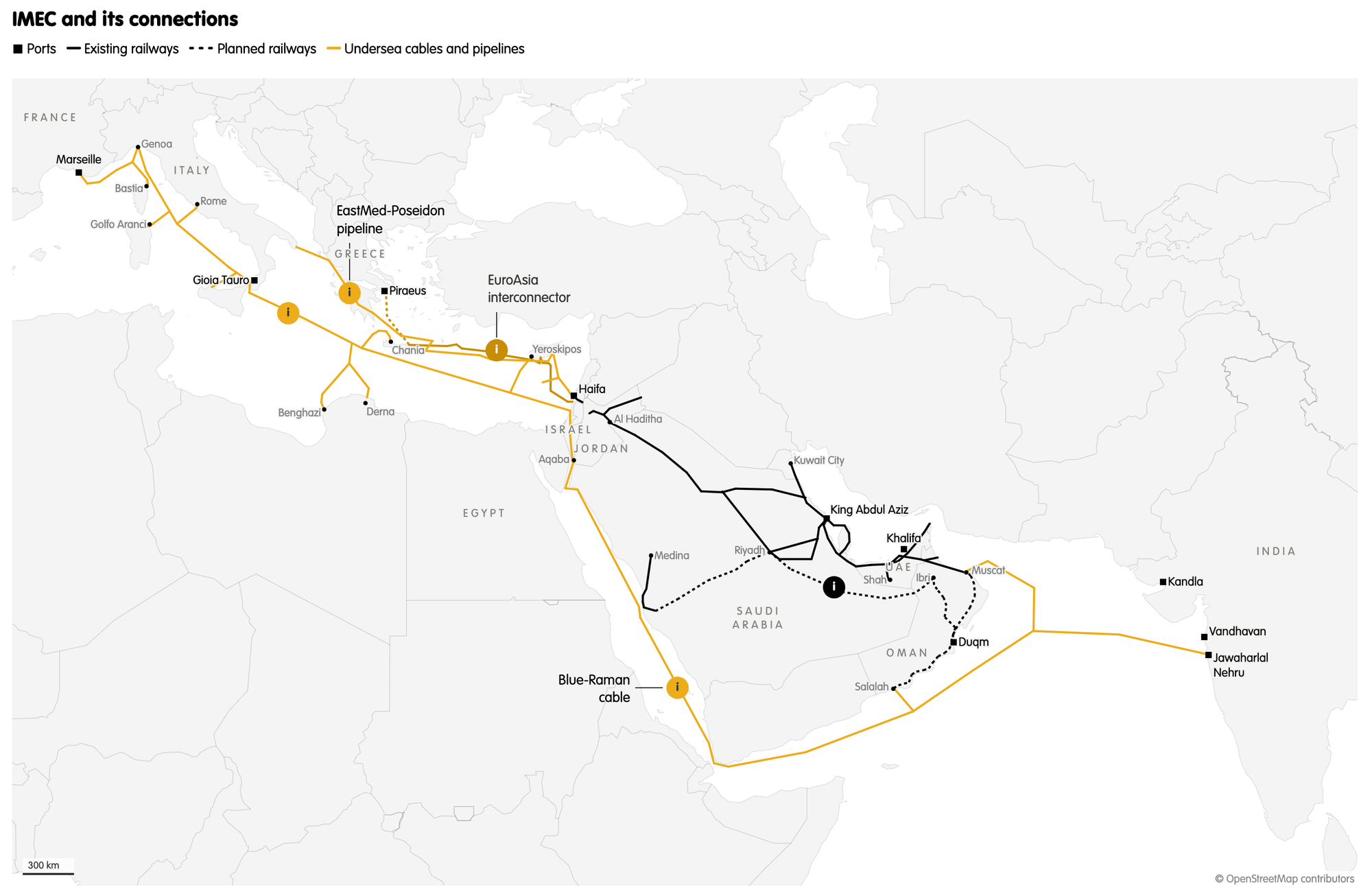

The proposal imagined Gaza not as a territory with a people and political rights, but as a logistics hub folded into the India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), the transport, energy and data corridor linking South Asia, the Gulf and Europe, via Israel, launched in 2023. In the plan’s diagrams, Gaza was to become a node of this east–west trade artery, its coastline and land rezoned for ports, pipelines and digital cables.

The leaked document was less a plan to rebuild Gaza than an add-on to the Abraham Accords, the US-brokered normalization deals struck in 2020 between Israel, the UAE and Bahrain, and later joined by Morocco and, to a varying degree, Sudan. Marketed as a diplomatic breakthrough, the Accords pushed the idea of “economic peace,” that trade, investment and infrastructure could stand in for political resolution. In practice, it meant connecting Israel into Gulf supply chains while sidelining Palestinian rights and sovereignty. IMEC takes that logic further, turning the promises of the Accords into concrete form: railways, pipelines and data cables that tie Israel even more tightly to Gulf and European economies.

The document even names Gulf rulers directly. In addition to an “Abraham Gateway” logistics hub at Rafah, it proposed an “MBS Ring” highway (after Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia) and an “MBZ Central Highway” (after Emirati president Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan). This vision seeks to fold Gaza into Israeli, Egyptian and Gulf networks under US trusteeship, merging Gulf capital and Israeli technology while reducing Palestinians to obstacles to be displaced or bypassed.

The IMEC was launched with great fanfare at the G20 summit in New Delhi in September 2023. The memorandum of understanding, signed by the United States, India, the European Union, France, Germany, Italy, Saudi Arabia and the UAE, promised nothing less than a new trade and energy artery. Its eastern leg would connect Indian ports to the Gulf. Its northern leg would run from the Gulf across the Arabian Peninsula and Israel to Europe. Railways, hydrogen pipelines, electricity interconnectors and data cables would build a “green and digital bridge across continents and civilisations,” in the words of European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen.[1]

For Washington, IMEC was never just a logistics project. It was a geopolitical anchor designed to counterbalance China’s Belt and Road Initiative by keeping India and the Gulf tethered to the transatlantic camp. European leaders, meanwhile, seized on it as a way to reduce their own vulnerabilities, both to Houthi disruptions in the Red Sea and to the Suez Canal chokepoint. They presented it as part of their Global Gateway strategy—a €300 billion plan to fund infrastructure, energy and digital projects abroad—launched in 2021 as the EU’s answer to China’s Belt and Road.

For India, IMEC aligned with Delhi’s ambitions to reposition itself as a global manufacturing and transport hub, moving its goods westward on faster, more secure routes. For the Gulf monarchies, especially the UAE and Saudi Arabia, the corridor dovetailed with their long-running strategy of transforming oil wealth into logistical centrality, positioning themselves as indispensable gateways for energy exports, container traffic and digital flows.

From the beginning, Israel was integral to IMEC’s design. The corridor’s northern route runs through its Mediterranean ports, with Haifa…now majority-owned by India’s Adani Ports & SEZ…positioned as the key gateway between Gulf terminals and Europe.

From the beginning, Israel was integral to IMEC’s design. The corridor’s northern route runs through its Mediterranean ports, with Haifa—privatized for $1.15 billion and now majority-owned by India’s Adani Ports & SEZ—positioned as the key gateway between Gulf terminals and Europe. Adani’s role ties the project back to India as well: Its ports on the country’s western coast, including Mundra, India’s largest container terminal, are slated to serve as IMEC’s entry point from South Asia. With Adani’s network of ports anchoring both ends of the corridor, IMEC has clearly been structured around major corporate players, not only state sponsors.

IMEC’s momentum has slowed since its launch, as Israel’s genocide in Gaza forced public celebrations of normalization to quiet amid widespread protests, but it has not stopped. India and European governments have renewed consultations and feasibility work to push it forward, and the leaked GREAT Trust proposal for Gaza brings it back centrally in US policy circles.

As public celebrations of normalization grew quieter, the underlying architecture, gas investments, arms contracts, trade agreements and digital cables, for the most part, continued to advance.

The Red Sea disruptions of late 2023 were a turning point. As Houthi strikes on shipping forced vessels to avoid the Bab Al-Mandeb strait, Israeli startup Trucknet Enterprise promoted a “land bridge” concept. The company announced agreements with firms including Puretrans FZCO, in the UAE, and DP World to move cargo overland from Gulf ports through Saudi Arabia and Jordan into Israel, presenting it as a way to bypass the maritime chokepoint.

Israeli officials touted the experiment as a faster route, but evidence of actual shipments remains hazy. Wary of appearing complicit in normalization during the war on Gaza, Jordan publicly denied that shipments were taking place. The sensitivity was underscored in May 2024, when Jordanian-Palestinian journalist Hiba Abu Taha was arrested and later sentenced to a year in prison after reporting on overland shipments through Jordan, charged under Jordan’s new Cybercrimes Law with incitement and spreading false news.[2] Official press releases and media briefings, however, have been less vehemently denied by the states involved. Whatever its status, the initiative offers an important glimpse of the kinds of connectivity schemes regional powers hope to advance.

If the land bridge previewed IMEC’s terrestrial leg, the Blue-Raman subsea cable (discussed in this issue by Ned Ledbeater) illustrates its digital backbone. Launched by Google with Sparkle (Italy’s telecom carrier) and Omantel, the system aims to link India directly to Europe through Israel. The Blue cable runs from Israel across the Mediterranean to Italy. The Raman cable stretches from India through Oman, Saudi Arabia and Jordan to Israel. When fully active, they will bypass Egypt’s long-standing monopoly on Asian-European internet traffic through the Suez corridor.

For Europe, the cable has become a flagship of its Global Gateway initiative, promising diversified data flows. For Israel, it marks a leap in regional integration, not only a land bridge for goods, but a switch point in the digital networks tying Asia to Europe. These projects show how IMEC’s promise of connectivity is advancing in practice, despite political denials.

If IMEC crystallizes normalization in the language of corridors and connectivity, its logic is not new. Earlier gas deals and energy contracts stitched Israel into regional networks long before the corridor was announced.

Much commentary on normalization has focused on the increasingly public arms trade between Israel and the UAE (the subject of Tariq Dana’s piece in this issue). Israel’s defense exports hit a record $14.79 billion in 2024, with about 12 percent of that going to Abraham Accords partners, the UAE, Bahrain and Morocco. Yet if weapons are working to bind security establishments, it is energy that now tethers entire economies together.

The most visible Emirati move came in September 2021, when the UAE’s Mubadala Energy (a subsidiary of its sovereign wealth fund), acquired a 22 percent stake in Israel’s Tamar offshore field from Delek for just over $1 billion. Tamar supplies much of Israel’s domestic demand and underpins exports to Jordan and Egypt. The investment marked the first time Emirati capital was directly embedded in Israel’s upstream gas sector.

Two years later, in March 2023, Abu Dhabi’s ADNOC joined with BP in a $2 billion bid for 50 percent of NewMed Energy, the Israeli company holding a 45 percent stake in the Leviathan megafield. The deal would have created a joint venture spanning Israeli and Egyptian gas assets, placing ADNOC at the heart of Eastern Mediterranean supply. Although talks were suspended in early 2024 amid the Gaza war and regional instability, the pause was tactical, not a cancellation.

Egypt and Jordan have also been bound tighter into this architecture. Both signed multi-billion-dollar import contracts for Israeli gas in the mid-2010s, and those flows have only intensified, a dynamic Hicham Safieddine chronicles in these pages. Indeed, in August 2025, Israel announced its largest ever export deal, a $35 billion contract to ship 130 billion cubic meters of Leviathan gas to Egypt between 2026 and 2040. The gas will feed Egypt’s Idku and Damietta Liquified National Gas plants, which then re-export to Europe, making Cairo dependent on Israeli supply even as it is bypassed by overland and digital corridors like IMEC.

Jordan, for its part, has relied on gas imports from Israel under a 15-year contract with Noble Energy (now Chevron). The arrangement has been politically toxic, triggering public protests in Amman, even as governments have consistently defended it as unavoidable for energy security. Yet, as Majd Bargash notes in his contribution to this issue, those claims were undermined this past summer, when Israel paused natural gas provision during its June war with Iran, underscoring the risks of Jordan’s energy dependency.

These deals show how normalization works through the nuts and bolts of extraction…Even when regional leaders rail against occupation or genocide, the gas keeps flowing.

These deals show how normalization works through the nuts and bolts of extraction. Emirati capital now sits in Israel’s upstream fields; Egyptian LNG plants depend on Israeli feedstock; Jordanian grids are powered by Israeli imports. Even when regional leaders rail against occupation or genocide, the gas keeps flowing.

Behind the headline deals lies a more uncomfortable fact, Israel’s offshore gas boom is built on unresolved jurisdictional claims. The Gaza Marine field, discovered in 1999 in waters allocated to the Palestinians under Oslo, has been kept off limits for decades, even as Israel has pressed ahead with extraction in nearby blocks. A 2019 UNCTAD report called this a systematic denial of Palestinian sovereign rights over their natural resources. Lebanon’s maritime disputes with Israel underline the same point: Much of the Eastern Mediterranean’s gas map remains unsettled. Normalization, in this context, cements an extractive order that lets Israel claim contested resources and shut out future alternatives.

This reality also undercuts the rhetoric of a so-called green transition. European leaders present IMEC as a future corridor for hydrogen and renewable energy, while Gulf states promote themselves as clean energy champions. Since the Abraham Accords, Israel and the UAE have highlighted joint projects on solar power, desalination plans and climate innovation as signs that normalization could deliver a regional green transition. In practice, however, these announcements remain secondary to the hard infrastructure of fossil fuels: billions invested in offshore gas fields, long-term export contracts and new liquified natural gas (LNG) routes to Europe. Rather than phasing out extraction, normalization has locked it in more deeply, with renewable rhetoric functioning more as diplomatic branding than structural change.

As Washington doubles down on its alliance with Israel while Brussels floats recognition of a Palestinian state, much commentary in recent weeks has contrasted US and European approaches to Gaza. But the difference is more a matter of degree than direction. The leaked US administration plan made Washington’s orientation clear: Gaza’s future imagined not in terms of sovereignty but as a logistics hub within IMEC—a project designed to deepen the Abraham Accords and hardwire Israel into regional trade, energy and digital flows.

Gestures like recognition of statehood allow Europe to position itself differently. Yet it has been an eager partner in the same US architecture, folding IMEC into its Global Gateway strategy, lobbying for EU financing and competing over which European ports will anchor the corridor. Recognition talk may sustain the illusion of action, but what matters is what gets built, the pipelines, ports and cables that entrench the status quo.

Saudi Arabia is often cast as the great holdout, reluctant to normalize until Palestinian demands are addressed. But here too, the difference is rhetorical more than real. Riyadh signed the IMEC memorandum in 2023, placing itself at the heart of a project that relies on Israel as its Mediterranean hinge. Saudi officials have repeatedly promoted the corridor as a future route for exporting hydrogen to Europe. As with Europe’s recognition talk, these gestures obscure the deeper reality, Saudi Arabia is already underwriting the infrastructures that embed Israel in the region.

Egypt and Jordan underscore the same paradox. Cairo voices unease about being bypassed by IMEC’s land and data routes, yet its liquified natural gas plants are locked into long-term contracts re-exporting Israeli gas to Europe, including the recent record $35 billion Leviathan deal announced in 2025. In Jordan, despite local protests, the Leviathan supply contract still binds Jordan’s grids to Israeli fields. Both Egypt and Jordan may signal solidarity with Palestinians in public, but their infrastructures tell a different story.

None of this makes the new US-led “regional architecture” seamless or inevitable. IMEC is riddled with contradictions. India has championed the project as part of its Viksit Bharat vision of becoming a global manufacturing and logistics hub, but relations with Washington are strained over recent Trump tariffs and protectionist policies.

At the same time, Gulf states that have signed onto IMEC as a US-backed corridor remain deeply tied to China. Saudi Arabia and the UAE send much of their oil eastward, making China their single largest trading partner.[3] Both have experimented with yuan-based settlements for oil and gas and continue to host Chinese firms in energy and logistics zones, even as they position themselves as key nodes in Washington’s alternative corridor.

Regional powers outside IMEC highlight the same contradictions. For Turkey, the corridor undercuts its long-standing role as the primary land bridge between Asia and Europe. Ankara has built its identity around being the indispensable transit hub, but a Gulf-to-Haifa-to-Europe route bypasses that position. The question for Turkey is how to adapt—whether by finding ways to plug into the corridor or by doubling down on alternative routes that preserve its relevance.

For Iran, IMEC is a project designed to exclude it altogether, binding the Gulf monarchies more tightly to Washington and Delhi while containing Tehran. The overall result is an architecture still in flux, celebrated by the United States and European Union, but riven with unresolved tensions over whether key regional players are to be incorporated or completely side-lined.

Beneath the fanfare of plans and announcements, it is these material ties that reveal where the new regional order is taking shape. Tracing these infrastructures—and contesting the visions they embody—matters now more than ever.

In the emergent US visions of connection and prosperity, Palestinians are cast as an obstacle rather than a people with rights, their dispossession treated as a technical problem to be managed away. But they have not accepted this erasure. They continue to resist projects of a so-called economic peace built on dispossession and ethnic cleansing. In that sense, the leaked document only makes explicit what the region’s unfolding infrastructure already shows: Normalization is being assembled piece by piece, through concrete, contracts and cables. Beneath the fanfare of plans and announcements, it is these material ties that reveal where the new regional order is taking shape. Tracing these infrastructures—and contesting the visions they embody—matters now more than ever.

The recent ceasefire agreement, mediated under Trump’s 20-point plan, retains many of the tenants of the GREAT Trust. It packages Israel’s military withdrawal and prisoner exchanges into a pause, without resolving the underlying problem of ongoing military occupation or Palestinian rights. In practice, its first phase mandates a ceasefire, phased Israeli redeployment and prisoner exchanges but leaves open who governs Gaza, who monitors security and who controls reconstruction. If such moments are understood as continuations of violence in another register, the question then becomes: How will the infrastructures of normalization deepen under this ceasefire? Which actors will control crossings, —cables, pipelines and funds—and at whose expense?

[Rafeef Ziadah is senior lecturer in Politics and Public Policy at King’s College London.]

[1] European Commission Statement 23/4420, “Statement by President von der Leyen at the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment event in the framework of the G20 Summit,” September 9, 2023.

[2] Elia El-Khazen, “ Truck Drivers at a Crossroads: On the Relevance of Trucking Communities to Regional and Global Anti-Normalization Movements,” in Disruptive Geographies and the War on Gaza: Infrastructure and Global Solidarity. Geopolitics, eds. Rafeef Ziadah, Christian Henderson, Omar Jabary Salamanca, Sharri Plonski, Charmaine Chua, Riya Al Sanah and Elia El Khazen, pp.1–39.

[3] Adam Hanieh, “Greening the Gulf? Renewables, Fossil Capitalism and the ‘East–East’Axis of World Energy,” Development and Change, August 6, 2025.

Rafeef Ziadah, "Hardwiring Normalization—Infrastructures, Extraction and Gaza’s Future," Middle East Report 315/316 (Summer/Fall 2025).