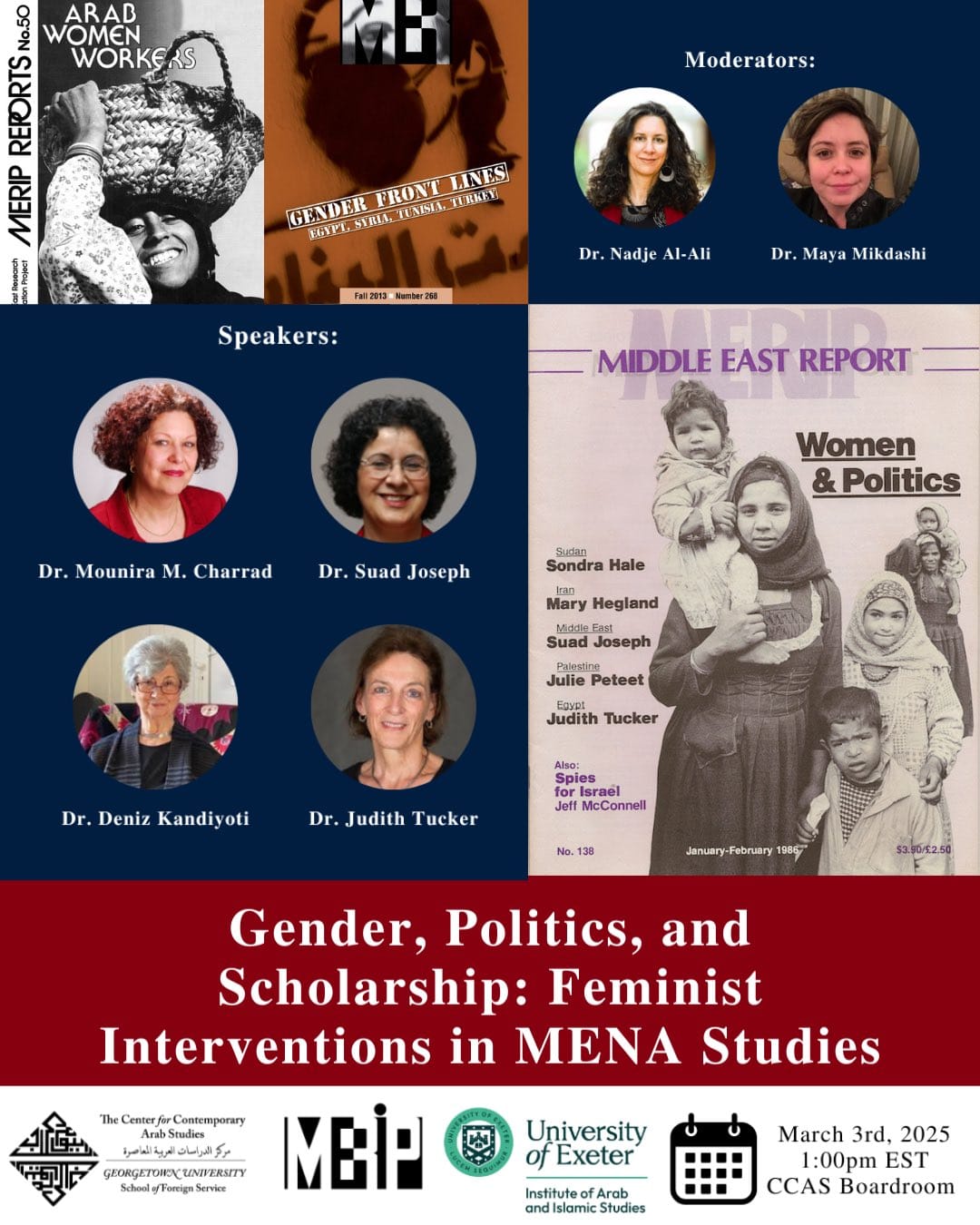

Gender, Politics and Scholarship—A Roundtable

On March 3, 2025, MERIP and the University of Exeter's Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies partnered with Georgetown University’s Center for Contemporary Arab Studies to host a roundtable on the past, present and future of feminist approaches to Middle East and North African Studies. The event brought together scholars and former MERIP contributors who have played pivotal roles in shaping the multi-disciplinary field of women's and gender studies within studies of the region. The discussion featured Deniz Kandiyoti (professor emeritus in development studies at SOAS), Judith Tucker (professor emeritus in history at Georgetown University), Mounira Charrad (associate professor of sociology at University of Texas, Austin) and Suad Joseph (distinguished research professor of anthropology and gender, sexuality and women’s studies at University of California Berkeley). They shared their experiences of how scholarship, organizing networks and areas of inquiry have taken shape over the past 50 years. In doing so, they also addressed a question at the heart of this issue: why gender matters now.

The roundtable was moderated by Nadje Al-Ali and Maya Mikdashi. It has been edited for length and clarity. The full video can be accessed in its original form here.

Nadje Al-Ali: I want to ask you all about the trajectory of the field of gender studies with reference to the Middle East and North Africa over the last 50 years. Can you speak about the kinds of challenges the field, or you personally, have encountered vis-a-vis the broader fields of gender, Middle East Studies and traditional disciplines? This links to bigger questions: What does a gendered lens contribute to our understanding of the Middle East and North Africa and does gender matter?

Also Read: "Shifting Approaches to Women and Gender in Labor, Politics and Society," MER issue 300, Fall 2021.

Deniz Kandiyoti: I think it would be fair to say that many of us on this roundtable had our formative experiences at a point in time when gender studies did not exist. There was a focus on women, which was very narrow. You might remember the first volume that came out in 1978, Women in the Muslim World, edited by Nikki Keddie and Lois Beck, which was trying to put together the scholarship at the time. The problem then was that the approach was mired in what we later called "Orientalism," a sense of Islamic exceptionalism, whereby we were frozen in a debate where women's rights were being read off of the foundational texts of the religion. This was happening at a time of interesting debates in the rest of the world about the effects of colonialism, spearheaded by Latin American Dependency Theory, which had barely made inroads into the Middle East. Judith Tucker's Women in Nineteenth Century Egypt (1985) and the first issues of MERIP were so important because they broke with that trend and brought a fresh political-economy perspective to the field for the first time.

There is much more to say, but we must remember that the way in which gender studies came into the Middle East field was shaped by at least three sets of influences that were in constant interaction with one another: social movements, the changing (international) governance structures around gender and academia.

It is clear that the way in which gender studies, and indeed Black Studies, developed in the Euro-Atlantic region and in the United States was as a direct response to social movements such as second wave feminism and the Civil Rights Movement. This is a different genealogy from developments in the Middle East. To understand these, you need to look at the events following the first International Conference on Women in 1975 in Mexico City—in which many of us participated. From that point on, the issue of women's rights and gender was shaped and appropriated by the UN system. In 1995, gender was incorporated into official policy documents with an infrastructure of gender training, gender planning and gender mainstreaming. Alongside national bureaucracies that monitored gender equality, the entire teaching and research infrastructure of women's studies, which later became gender studies, started in the Middle East and the Global South after the impetus of the 1975 conference. The third institutional leg of these developments is to be found in academia and the growth of scholarship with distinctive preoccupations. Although the Western academic canon was widely disseminated throughout the world, studies of gender remained context-specific and responsive to regional crises and geopolitical flashpoints.

In North America, many people associate gender studies with post-structuralism and discourses about the fluidity of gender. In fact, the study of gender also has another genealogy in terms of its relation to global governance institutions: Women-targeted projects were not yielding the results expected, and gender was proposed as a relational concept that targeted the entirety of relations between men, women and generations. This social relations approach was more materialistically grounded. The idea that institutions themselves were gendered—whether we're talking about the state, the market, communities or households—eventually took hold, but it lost its salience with the shift to more dispersed sites such as bodies, sexualities and gendered identities.

When we ask, "Why does gender matter?" I think we need to qualify this by different understandings of gender which have shifted through time. Scholarship has been buffeted by and responded to events. After the 1979 Iranian revolution, we had a long-lasting wave of Islamic feminism asking: Is it possible to find feminist voice within Islam? From the 1980s onwards, with the Infitah [“opening up,” or liberalization], we had a burst of civil society activism which foregrounded Muslim actors and influenced the scholarship. After 9/11, we had the revival of the colonialism debate and the issue of “feminism as imperialism.” Indeed, with contributions from Nadje Al-Ali and Nicola Pratt looking at Iraq and Lila Abu-Lughod looking at, more broadly, the Muslim world and Afghanistan, it seemed that we'd come full circle to the original debates that Leila Ahmed had put on the agenda in the early 90s. Finally, the Arab Spring influenced so much of our scholarship, and now this dire moment of catastrophe which is unfolding in the region—these elements form the backbone of the contexts in which we operate.

But early on, we had this political economy push and it was very much in reaction to or in denial of an Orientalist reductionism of women to “what Islam says about them.”

Judith Tucker: I will add a few things that might apply more directly to the discipline of history, which shares many of the characteristics that Deniz has raised. So much has happened in the region during the last decades and our scholarship has been very affected by the political developments that we have lived through. In part, this is a result of what we usually term in history the "presentist orientation" of many of us in the field—because most, if not all of us, are very connected and concerned with what is going on in the region.

Having said that, like all scholars we are also part of an intellectual world and influenced by broader intellectual trends. As Deniz mentioned, early on it was political economy and material history. For me the Neo-Marxist trends were extremely important. Deniz kindly referred to my work as being important, but I was not alone. There were towering figures, women, who were working on other regions at the time, if not as much on the Middle East. I learned and borrowed from them. But early on, we had this political economy push, and it was very much in reaction to—or in denial of—an Orientalist reductionism of women to “what Islam says about them.” But I do think that we threw the baby out with the bath water, in retrospect. For a while, there was a studied refusal to deal with culture and religious culture in particular.

As Deniz said, certain events—like the Iranian Revolution, or the power of Islamist political movements—refocused our attention on coming to terms with a certain local tradition and sense of identity that we would find among many women of the region. Personally, I was quite influenced by Fatema Mernissi, the Moroccan sociologist, who raised this call, urging us to think about revisiting the Islamic tradition and understand better what happened on a material basis—but also how texts were variously interpreted over time. That influenced my work in my post-political economy period, when I was more focused on Islamic texts, particularly juristic texts.

Suad Joseph: Anthropology is probably among the disciplines which have contributed most to the study of women in the Middle East. But there was hardly anything in anthropology in the 1970s, which is my generation and Deniz's generation, and Judith was just a couple of years behind us.

If we take 1970 as our starting point, until the 1990s most of the work was very ethnographic: on the ground, local, descriptive, with very little analysis. This came after the 1967 War, which generated a general sense of defeat—the defeat of Pan-Arab nationalism, the defeat of the states and, in some sense, the defeat of the student movements. That was formative for me because I was at Columbia in 1968 with the student uprising. Even though the student movement was oddly not so gendered, the women's movement side-by-side with the student movement and the Civil Rights Movement brought a global perspective that seeped into Middle East Studies. An important shift came with Edward Said's Orientalism, published in 1978. While it had very little to say about gender, Orientalism itself was gendered, and feminists were able to intervene in that conversation.

I agree with Deniz that the 1975 Mexico meeting was a herald of things to come, with the UN Decade for Women (1976–1985), followed by 1985 Nairobi [the third World Conference on Women], and 1995 Beijing [the fourth World Conference]. And, remember, there was also CEDAW [the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, a UN treaty] in 1979 and a whole series of conventions, including later the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

The Islamic revolution in 1979 triggered an interest in the veil. Women's clothing became the topic of so much of the conversation, but it was very difficult to have conversations with scholars because very few outside the Middle East read our work. We were not well-read outside of our own community. If you were teaching feminist courses, which I began doing in the 70s, there was very little literature to use. When Lila Abu-Lughod's Veiled Sentiments came out in 1986, it was one of the few books that was being used ethnographically. Rosemary Sayigh's work, The Palestinians: From Peasants to Revolutionaries (1979), came and then in 1994, Too Many Enemies, focusing specifically on women. In 2005, Voices: Palestinian Women Narrate Displacement, illustrated the importance of oral histories, documenting women where they were located. Because if you look at the gendered lens as a lens about power—where are women located in relationship to power? What keeps them there? What are the structures of society, the structures of labor, the structures of representational discourses and where are women located in relationship to these? Where is resistance?—then understanding women's voices and the oral history tradition that Rosemary led is very important.

By the late 1990s, an important turn prompted us to begin looking more at global factors and the state. Scholarship became more analytical, more theoretical. Yes, we imported many of the theoretical frameworks from feminism in the West, but we also recognized the need for indigenous frameworks to emerge. Islamic feminism was one, but many of us had concerns and dedicated significant time to addressing them. The period from the 1990s into the early twenty first century was pivotal in terms of theoretical and critical analytical work and the production of phenomenal new generations of scholars.

Another fascinating turn was research on sexualities and bodies. The publication of journals like Kohl in Lebanon marks a shift from the very particularistic research that had been a characteristic of the 1970s to the 1990s and creates an interface on a global stage.

To summarize, a periodization I like for understanding women and gender research within Middle East Studies begins with the initial wave of research in the 1970s to 1990s; followed by the 1990s to the early 2000s as a bracketed period of research on the state and on citizenship and on women's rights, in part generated by the UN Decade for Women; and then post-2000, an emerging emphasis on the body and sexuality. [Reinforcing the breadth of this scholarship and the periodization mentioned here, a transnational research team, Mapping the Production of Knowledge on Women and Gender in the Arab Region recently launched a database cataloguing this literature between 1975 and 2022, more than 20,000 references.]

It has been a period of chronic warfare, chronic violence, chronic dislocation of peoples…We need to more clearly understand the politics of knowledge production amid global dislocation in the region...

I also want to put in the backdrop that what was happening on the ground in the Middle East, especially in the Arab region, was traumatic, violent, chronic warfare: the Lebanese civil war from 1975 to 1990, the Iran-Iraq War from 1980 to 1988, the chronic wars in Yemen, the occupation of Lebanon for 20 years, the 2006 Israeli invasion in Lebanon, the First intifada, the Second Intifada, the 2011 revolutions, which were largely defeated. It has been a period of chronic warfare, chronic violence, chronic dislocation of peoples…We need to more clearly understand the politics of knowledge production amid global dislocation in the region, caused both by internal forces as well as regional and global forces.

Mounira Charrad: To my mind, the answer to the question of why a gendered lens matters and what it contributes to the study of the region is very simple. The study of gender contributes to the study of any region in the world, including ours, and the issue for us is more that Middle Eastern studies scholars have looked at institutions without paying attention to gender. But all institutions are gendered everywhere, including in our region.

To the question of the trajectory of the field, I will add a couple of points from the perspective of my discipline, sociology, which is the latecomer to the study of gender in the region. It is also a field that remains much less represented than anthropology, history and political science.

In addition to the challenges already discussed, scholars in my generation were facing an approach to gender in sociology that made two claims that many of us then had to confront. One claim concerned feminist agendas needing to be the same or very similar throughout the world. Those of us who looked at Latin America, the Middle East or Asia were asserting that this imposed a feminist agenda onto the global world in a way that didn't make sense to us. We were aware that our agendas could be different and that they could be feminist while being different, so the issue of agenda was key. A second dominant issue at the time concerned the relationship between state and gender—the claim that the state is patriarchal was a blanket statement. Some of us agreed that states are patriarchal, extremely so in some parts of the Middle East and North Africa, but we also were aware that not all states are equally patriarchal or patriarchal in the same ways. In sociology, we needed to confront and debunk these two main claims.

Maya Mikdashi: You have spoken a bit about how our work is in constant dialogue with a region in turmoil, but can you speak about how your work has developed throughout your careers? Who has influenced your thinking? What are the key questions that you have been interested in and how have they shifted over time?

I was not a feminist when I started field work. What made me into a feminist was my field work...

Suad: I think about these questions a lot because I am puzzled by my own history, by how I got to where I am—nothing would have predicted this. When I began graduate school, I was very unformed theoretically. To the degree that I had any theoretical grounding, it was mainly Durkheimian and Marxian, but I was at Columbia during the 1968 strike and that was an incredibly transformative moment. So, it was not any person, it was the events, and it was being a part of that student movement. I was part of SDS (Students for a Democratic Society) and then the falling out of the madness that the SDS became. But the key variables were always class and the state. I took the commitment to understanding the state and class to the field with me.

I was not a feminist when I started field work. What made me into a feminist was my field work because when I came back from the field, I realized that my data was overwhelmingly about women, and I had to understand it. I started asking people, “Who do I talk to? How do I understand this data?” I was simultaneously asked to teach a course on what was then called “sex roles.” I was at Hofstra University at the time, and I was led to Rayna Reiter, now better known as Rayna Rapp, and she introduced me to a group of Marxist feminists—people like Gayle Rubin, Louise Lamphere, Karen Sacks. I was already a Marxist, so that was an easy transition. We were reading together, we were writing data, we were thinking together, and none of them were of the Middle East. That was the vacuum for me. Apart from Deniz in England, there were very few people in anthropology who were doing this kind of work at that time. Later, when I came to University of California-Davis, no one was working on the Middle East here. I was literally the only one regularly teaching on the Middle East, so there were very few people to talk with. I would go to the Bay Area where there was a Middle East seminar, but there weren't feminists among those. I decided that if I couldn't find people to talk with about Marxism and feminism, about women in the Middle East, about the Middle East at all, then I had to create organizations to do that. Several decades followed in which every time a question came up, and I wanted to find people to work with, I created an organization to do that.

I started the Middle East section of the American Anthropological Association (AAA) when I was still a graduate student at Columbia because there was no one to talk to within anthropology, and a panel that we had suggested was rejected. Then came the Association for Middle East Women's Studies (AMEWS). We started the Women's Studies program at UC Davis in the 1980s. There was no one to talk with about families, which is an area that I was increasingly interested in, so I created the Arab families working group. Then, I wanted to get scholars on Lebanon talking with scholars here, so I created a consortium called the University of California Davis Arab Region Consortium that included the AUB, AUC, LAU and Birzeit (co-founded with the Arab American Studies Association), and on and on. As a result, I never published a book because I was spending my time creating these organizations that provided enormous gratification and networks. The latest organization is the Middle East South Asian Studies program at UC Davis.

What ran through all of that work was class and state. No matter which issue I took up, I always looked back to connecting with class and the state. I was born in a country (Lebanon) with a very weak state, then I grew up in a country (the US) that had a very strong state, and going back and forth between the two always struck me. I studied women, then women's networks, then family and then citizenship, which led me to the study of looking at relational rights and the self—and they produced a bundle of concepts that continue to loop back to the state and class.

Now, the violence I mentioned earlier and the genocide in Palestine has led me to look at the concept of trauma and question how we can develop a concept that is useful, appropriate and relevant given the conditions in Palestine, in Lebanon, in Syria. We need to have a different understanding in places where the framework of post-traumatic stress is not relevant. There is no "post." The trauma is ongoing. It is generational. It is not individual. It is societal. We need a different approach. And somehow all these pieces are connected, leading from the initial work on politicization of religion in the state to looking at how women acted, to looking at the family, to looking at notions of relationality—all connected with wasta [the use of personal connections and influential relationships to gain advantages] and networks. Somehow that bundle produced itself. I did not go out to study any of this. I didn't have a framework in mind other than class and state. In my case, the field led me; I don't think I led the field. It was what was emerging that I felt I had to address in some way.

One of the reasons that I became a historian, and what has really shaped the field of Middle East women's and gender history, is the recognition of the importance of the imperial and the colonial in the modern period...

Judith: Like Suad, I was active in the anti-war movement on campus in 1968–1969. But that wasn't really what propelled me. After I finished college, I went to Beirut for two years. It was at the time when the Palestinian revolution was fully ensconced there and in flower. I remember being so struck by women and a certain rhetoric about how important women were in this revolutionary movement. I'm not saying that the reality always lived up to the posters and the discussion, but coming from the US Left, I thought, “wow, this is so much better than what I'm used to in terms of how the left deals with issues of women's participation, etc.” I became very interested in women's history and women's history in the Middle East as a result largely of that experience. In those days “gender” was not a word we used. I did my original work in Egypt and the journey was really one that, as I mentioned before, started very squarely based in political economy.

One of the reasons that I became a historian, and what has really shaped the field of Middle East women's and gender history, is the recognition of the importance of the imperial and the colonial in the modern period, how much that has shaped everyone and everything from the individual right up to the state and our need to study that process very carefully. Many historical studies of the various ways in which Empire deployed gender are still so relevant to what happens today.

I kind of fell into my subsequent projects because I worked in the Islamic court records. They became such an important source for studies of women and gender, particularly during Ottoman times in the region. In the beginning, I worked in them very uncritically, just mining them for data. Then I became curious, ultimately, about what was really going on here. Why Islamic law? Why the courts? What lies behind this? Then I grew interested in a much broader study of Islamic law itself: Islamic law and gender issues, Islamic law and society. What was that historical trajectory? How do we understand the epistemological break that we see with the emergence of the modern state, taking control, codifying the law and so forth? I got in through the back door into issues of state as well.

In reflection, I would add one more thing about how much we are influenced by what happens on the ground. As Suad pointed out, it has been a very violent time. That encouraged me to look at the issue of piracy in the eighteenth century and ask questions about gendered violence. What did it look like in an earlier time in the region? Those are some of the major influences for me.

Kinship seemed central because there were groups that were resisting the state, or, on the contrary, aligning themselves with state, that were based on kinship, and since these groups were patriarchal, it informed how women's rights developed.

Mounira: I see two things that influence my thinking. First, I'm from Tunisia. I grew up in Tunisia. I went to college at the Sorbonne in Paris and then graduate school in the US. Wherever I was, women from other parts of the Middle East and North Africa would come to me and say, “Oh, how lucky you are to be from Tunisia. Women in Tunisia have rights that no other country has.” In graduate school, I was plunged into the study of comparative historical sociology. I was in a department where you could do quantitative work or you could do comparative historical work. Basically, there was very little ethnography at the time in that department. I was drawn to comparative historical sociology, and I think, because I'm a woman from Tunisia, several people on the faculty and elsewhere expected me to do a study illustrating women's subordination somewhere in a community or in families in Tunisia as my dissertation. As stubborn as I was, and as interested as I was in comparative historical sociology, I wanted to understand big developments in the region, and the methodology that I learned had been applied to issues of wars, revolution, political systems, democracy, dictatorship and so on. I thought, well, how about gender? How about women? How about women's rights? How do those long term, broad developments impact women's rights? So that's what I wanted to study. The reaction I got was, “wow, you're using a big gun to shoot a small bird.” My reaction was, “no, women's rights, that is not a small bird, that is a big bird!” I am using big guns to understand big birds.

That's how I got into the study of the development of states. Then I found another challenge concerning how states in the region are studied. Growing up in a colonial/post-colonial situation where elite schools were teaching French, I learned French history and very little history of Tunisia. But when I looked at the history of Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco, I found that the development of states had to do not only with the relationships between state and class, governance and class, rulers and class, but also with how states related to what I have called “kin-based solidarities:” groups organized along kinship lines and held together by a sense of belonging to a common kinship line, a common ancestor, and not necessarily by social class. That's how my work developed step by step: First looking at women's rights in my dissertation and later developing an analysis of how states emerged and change historically from the pre-colonial period to the post-colonial period. Kinship seemed central because there were groups that were resisting the state, or, on the contrary, aligning themselves with state, that were based on kinship, and since these groups were patriarchal, it informed how women's rights developed. Just two days ago, I read an article about how Hamas relates to and organizes the population. Not surprisingly, kin groupings come into play. Kinship shapes how groups are held together. Hamas is totally aware of the significance of what brings and holds people together, particularly in situations of violence, trauma and destruction.

Now, my interests have changed. I went from wanting to study structures, states and broad institutions to a focus on agency in my current work. I want to understand how women's movements, feminist movements, develop and survive in situations where it's not easy to survive: what strategies they use to survive and to find a voice when conditions permit. My shift really has been from structure to agency.

My own experiences of being on the ground and seeing how women were actually coping day-to-day with living in patriarchal structures led me to “bargaining with patriarchy.”

Deniz: I think it will seem very unacademic to say that my formative experience was growing up in Istanbul as a girl. It may seem strange that you can have a nine-year-old proto-feminist, but that's exactly what happened. The inspiration for my work on patriarchy was formed when I was in primary school, basically. My work took off in the 1980s when I left Turkey and came to London, and I was confronted by two sets of scholarship that gave rise to great dissatisfaction. One was feminist scholarship itself, which was dominated by big debates about capitalism and patriarchy. You had radical feminists, socialist feminists, liberal feminists battling it out, trying to decide whether these were independent systems of oppression or whether they work together. My own experiences of being on the ground and seeing how women were actually coping day-to-day with living in patriarchal structures led me to “bargaining with patriarchy.” I was arguing that each system of male dominance creates its own areas of wiggle room and different forms of consciousness, including conservative consciousness. This is much more relevant today than I imagined because the particular patriarchal bargain I was talking about—based on women's obedience and submission for male protection—seems to have quite a few buyers among Trump-supporting women as we saw in the latest election. But in relation to feminist theory, the patriarchal bargain was my main contribution.

In relation to the Middle East, I was extremely frustrated by what seemed a very sterile approach to women's rights in the region. This motivated me to contribute Women, Islam, and the State because I was quite interested in how histories of state formation and nationalism inflected the ways in which Islam came into the picture. Maya [Mounira Charrad] was doing her PhD at that point, and I also drew on her work with the comparative study of Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco. As I became more involved in scholarship in the United States, I started feeling rather desperate about the sterility of the field. We seemed to be stuck in a groove. We were back discussing Islamic feminism as if the state moment had never happened. Also, the Zionist/anti-Zionist axis in politics, which was much sharper in the United States, drove me to despair, and I simply made a cowardly exit from the field. I started working in Central Asia, and from 1995 to 2000 I worked on Uzbekistan. Then I started working on Afghanistan between 2002–2204.

The Arab uprisings drew me back to the field. At that point, I was already retired. I was working for a webzine called Open Democracy, where I was monitoring the gender effects of the Arab uprisings. This gave me an opportunity to provide a platform for my friends in the region to write about that moment from Cairo, from Tunisia and from the environing countries like Saudi Arabia and Iran. I realized that my model of patriarchy was outdated, that it needed urgent revision, because I was seeing new patterns on the ground with respect to the sorts of violence being deployed: politically motivated gender-based violence. Whereas I had been talking about the kind of violence that takes place in families, in communities, in tribes where everything is hushed up, this violence was public, anonymous and state-sanctioned in many places. So, I moved away from patriarchy and coined the term "masculinist restoration," which refers to the will to reassert male domination and privilege, through coercion if necessary, at a point where patriarchy is no longer hegemonic and you have new forms of mobilization and political consciousness.

The rise of right-wing movements across Europe, in the United States and further afield has both vindicated and challenged my concept of masculinist restoration.

I was very influenced by what was happening in the Middle East—in Tahrir in Cairo and in Istanbul during the Gezi uprisings in 2013. I saw the newer generation who were aware that gender issues were actually about governance itself. It was about the desire for a pluralistic, democratic society vis-a-vis the patriarchal pretensions of autocracies. My assumption at the time was that there would be new cross-gender alliances—groups of men and women fighting for democracy, for pluralism, for inclusivity, versus men and women fighting against it. The rise of right-wing movements across Europe, in the United States and further afield has both vindicated and challenged my concept of masculinist restoration. For instance, in the 2024 election campaign in the United States, constituencies of young men with violently misogynistic views, such as the so-called incels, were being openly courted as the issue of male privilege was put on the agenda. My expectations concerning the role of youth as a bulwark against autocracy, on the other hand, were challenged. Statistics showed a growing gender gap in political preferences with more young men than women voting for right-wing movements both in the United States with Trump and in Germany among supporters of the far-right Alternative für Deutschland. Youth could apparently be divided by their gender interests.

Yet, I refuse to resort to the concept of “backlash” to explain these outcomes: the idea from political science that when [newly] empowered groups start affecting policies on the ground, aggrieved majorities who feel disempowered try to claw back whatever rights and spaces they may have acquired. I think reliance on this concept prevents us from looking at feminism and feminist approaches more critically. First, I was very critical about the way in which gender was incorporated through governance tools: Instruments, such as gender mainstreaming, have been co-opted and appropriated especially in the countries of the Middle East and North Africa, where they became a fig leaf for autocratic governments simply gesturing towards inclusivity of women. I also expressed unease about how the Western canon, which continued to be influenced by local social movements around sexual liberties and LBGTQ platforms in the West, was being disseminated globally in mechanical and unproductive ways. This came home to me most forcefully during gender training sessions in Kabul where Afghan women who had been unable to leave their homes without a related male chaperone (mahram) under the Taliban were being taught about gender a fluidity in a context where gender relations were coerced and subject to direct policing—as they still are.

I am now interested in revising my concept of masculinist restoration because I believe we have reached a moment of unprecedented global crisis in gender relations. It is superficial to dismiss the moral panic about the demise of the heterosexual family fueled by the conservative right—although their scapegoating of gay and trans communities is totally off the mark. The fact is that birth rates are declining sharply globally and family formation is delayed or altogether bypassed in a context where the commodification of care and diminishing public access to support for social reproduction (in the areas of education, health and shelter) creates new pressures and obstacles. It is quite significant that the lowest birth rates and ratios of women choosing to remain single are highest among the most patriarchal societies of east Asia such as South Korea and Japan. The crisis of social reproduction is most dire in the Middle East where the fragmentation of states and escalating conflict put even conditions for bare life under threat—as is most evident in Palestine—and make the development of a gender agenda even more complex.

This brings me back to Nadje's first question: why does a gender lens matter? A gender lens now is not merely about gender identities and rights. Gender has become a key mobilizing issue in politics. Think of Iran, and the “Woman, Life, Freedom" demonstrations that started in 2022. The authorities were barely able to put them down a year later, using massive repression. Protesters knew that this wasn't about women veiling or unveiling but about the sort of regime they were unwilling to live under. Although this may be an extreme example, mobilizations around gender are at the heart of battles around the nature of polities and the vital struggle for democracy.

What I would like to explore is whether we really understand this moment. Are there elements of hope? How can we form an agenda to mobilize the forces that are able to act as a counterweight to the various forms of autocracy that are germinating everywhere in their own way? And how do we understand the global alliances that form around gender, which are now much broader?

Read the previous article.

Read the next article.

This article appears in MER issue 314 “New Gender Frontlines.”