Extractive Agribusinesses—Guaranteeing Food Security in the Gulf

The 2022 Food and Agriculture Organization report on food security and nutrition in the Arab region makes for bleak reading.

Between 2014 and 2021, the total number of Arabs suffering from moderate to severe food insecurity increased from 120 million to 154 million.[1] This insecurity, however, was not distributed evenly across the region. In the same period, the Gulf states saw a decline in food insecurity, from 11.3 million to 10.3 million people.

Today GCC states—which import around 90 percent of their food—rank among the world’s highest in terms of food security and affordability, on par with many OECD states. Their citizens spend a relatively low share of their income on food. In Qatar, for example, the population devotes an average of 12 percent of their pay to food—similar to Germany, the Netherlands and Australia.[2]

These regional disparities speak to longstanding efforts of Gulf states to manage a stable and affordable food supply. Below ground the prodigious reserves of oil in the Gulf have allowed rapid growth and development. But above ground, these states are poor in agro-ecological resources. The amount of arable land is low and rainfall is minimal. The booming cities, vast commercial real estate projects, tourism sectors and service economies thus all depend on the import of diverse low-cost foods.

In recent years, Gulf economies have tackled their food dependencies not just by importing foodstuffs but through land enclosures, or the purchasing of agricultural land abroad, particularly in the Middle East, North and East Africa (but also as far as the United States and Australia). They have also increasingly invested in food value chains: using their purchasing power to buy raw goods from other countries for production and export. Mainstream economic policy proposes that such trade between the Gulf states and other Arab countries is mutually beneficial. International finance institutions, like the World Bank, encourage poor countries to pursue growth by liberalizing their agricultural markets, expanding food exports and increasing foreign investment in their agribusiness sectors. They tout these policies as a way to resolve food security, rural development and trade imbalances.

Amid rising concerns about the environment, policy makers also argue that such trade can resolve ecological scarcity. Countries with arable land and water can meet the food demand of countries that are not endowed with such resources. One article in The Lancet in 2014, captures this view, arguing that more amalgamation between states in the Middle East could address crucial shortages: “regional ecological integration around exchange of water, energy, food, and labour, though politically difficult to achieve, offers the best hope to improve the adaptive capacity of individual Arab nations.”[3]

But this framework fails to account for the environmental aspect of agricultural commodity production. Agricultural extraction might ensure cheaper food prices in the Gulf states, but it has an ecological cost in the growing country. Indeed, rather than a panacea, the acquisition of cheap land and water to grow raw materials for export to the Gulf fits into broader efforts of more aggressive Gulf states, like the UAE, to expand extractivist circuits into Africa. The GCC states, through agribusiness and food, thus play a role in the reproduction of peripheries in the Middle East and Africa.

As far back as the 1970s, wealthier Gulf countries have been acquiring land in foreign locales for farming. But the exhaustion of water reserves in the Gulf combined with the 2007–2008 food crisis accelerated this strategy.

According to the Land Matrix database, between 2000–2022, Gulf states acquired more than two million hectares of agricultural land abroad.[4] Over a third of it was in other Arab countries. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar and Kuwait acquired some half a million hectares in Sudan. Egypt is another site of significant Gulf purchases at 157,851 hectares.

These purchases are characterized by their industrial scale, the social and ecological rupture they engender and their extractivist nature.

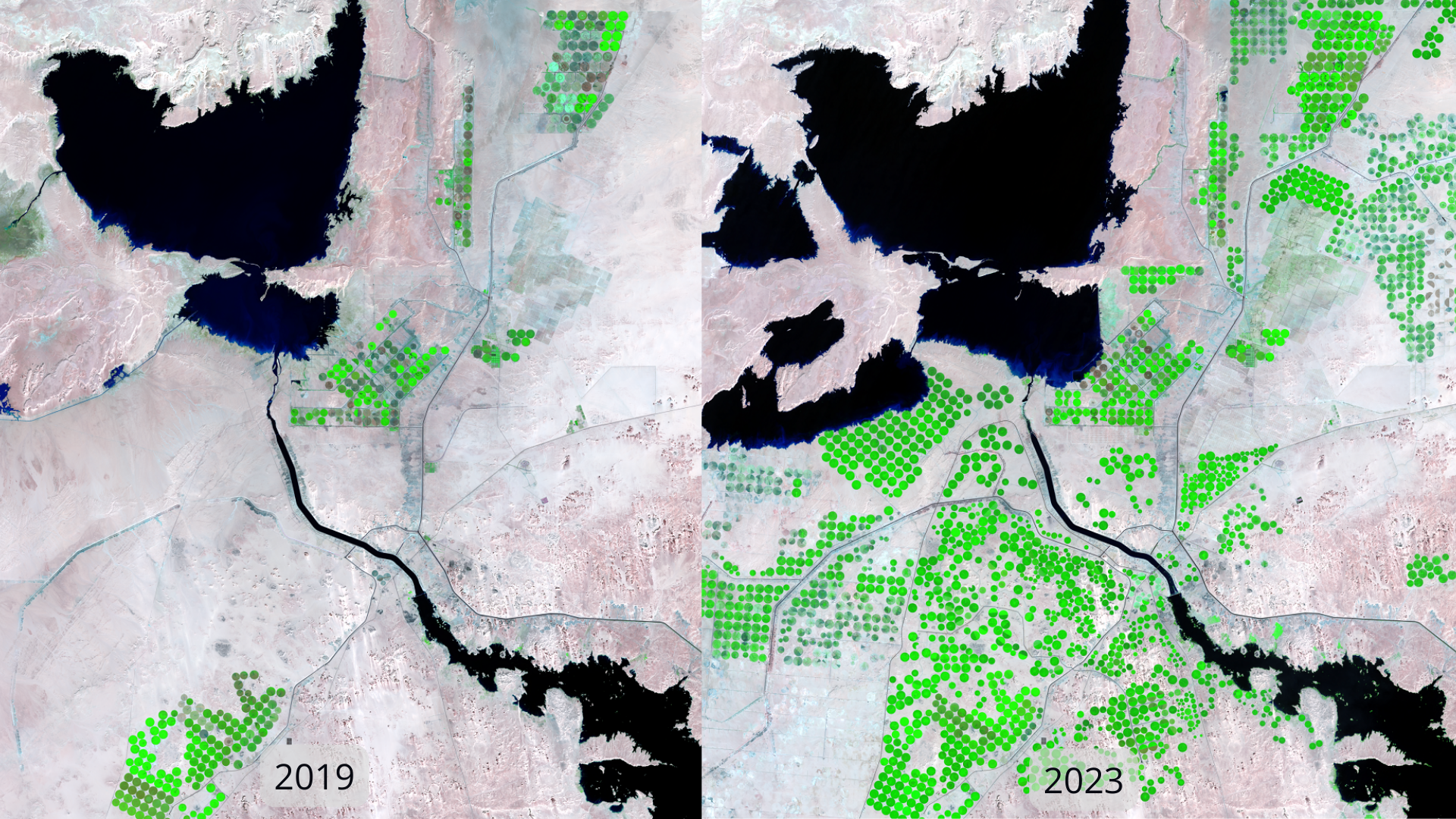

These purchases are characterized by their industrial scale, the social and ecological rupture they engender and their extractivist nature. For example, in Toshka, an area in southern Egypt, Emirati and Saudi agribusiness companies like Al Dahra and Jenaan, own around 120,000 hectares of land. Toshka has a large allocation of Nile River water. The pump that transfers water to the site from Lake Nassar, was, at the time of its construction in the 1990s, among the largest in the world. Here, land is transformed into industrial agricultural space through the intense application of chemicals, fertilizers and technologically advanced machinery.

Fields in Toshka are irrigated by automated booms that can cover 120 acres in a single rotation, while tractors and other machinery use GPS devices to ensure the precise application of chemicals and water. The site itself is the legacy of dispossession from native land users, including more than 40 Nubian villages that were evicted in the 1960s prior to the construction of the High Dam. These enclosures supply raw commodities such as cattle feed for processing in Egypt and for export to the Gulf states.

In Ethiopia, Saudi Star, a company owned by a Saudi-Ethiopian businessman, acquired 14,000 hectares in the state of Gambela. Though its success has been limited, the project is emblematic of the violence that accompanies these enclosures. The land belongs to the ethnic minority Anuak people, who were cleared as part of Ethiopia’s so-called villagization policy, a scheme introduced in 2010 to compel rural inhabitants to vacate their land and move to new settlements.

Because many held no formal legal title to their land, it was classified as unpopulated and sold to investors without compensation to the indigenous inhabitants. Their dispossession led to considerable unrest. In 2012 armed men attacked the project, killing a number of the company’s guards. Ethiopian troops responded by assaulting the villages near the farm. The soldiers reportedly killed and tortured men and raped women—violence that forced hundreds of villagers to flee to neighboring South Sudan.

One of the most common crops grown on Gulf-owned land enclosures is cattle fodder such as alfalfa. Its regional trade encapsulates the dynamic of ecologically unequal exchange.

Alfalfa is a water-intensive crop that is costly to grow in the arid environment of the GCC. But it thrives in regions like the Nile Valley. Dairy operations established in many Gulf countries, including Al-Safi of Saudi Arabia—one of the largest dairy farms in the world—depend on it. As a result, livestock feed has become a regular regional trade, with one UAE company sending weekly shipments of alfalfa and other forage crops from Egypt and Sudan.

Also Read: "Land, Livestock and Darfur’s ‘Culture Wars’" in MER issue 310, Spring 2024

Granting large areas of land to investors to grow and export cattle feed crops back to the Gulf is questionable given the high levels of food insecurity in many African countries. The arable land and inputs like water and fertilizer that are given over to such feed crops are directly removed from the production of subsistence crops for human consumption. Instead, this land is used to produce livestock feed for the Gulf, while domestic populations rely overwhelmingly on imported grains. The result is acute food insecurity. In Sudan, for example, an estimated 12 million people, out of a total population of 44 million, face acute food insecurity, a crisis partly caused by the country’s civil war.

This underconsumption takes place as Gulf plantations continue to extract value from the country. Company documents I examined during the course of research predicted that one farm of 88,000 hectares in Sudan’s Wad Hamid would produce an annual revenue of $86 million—profit created through the extraction of water and soil wealth, the national resources of Egypt and Sudan.

The full cost of scarce water, soil nutrients, pollution from fertilizer and pesticide use and other natural matter are not included within the commodity price. Recognizing the full cost of agricultural commodities gives a more accurate depiction of the real value accrued to the Gulf states through food trade and the acquisition of agricultural land. The transfer of value that is facilitated by this trade is a significant feature of the Gulf’s states’ economic growth.

The scale of the Gulf’s food trade is substantial. In 2018 the entire Middle East and North Africa region (all Arab states, Israel and Iran) imported food that had a value of $103 billion. Of this amount around half went to the Gulf states, even though these states account for only 11 percent of the region’s population.[5] The same imbalance is clear in the weight of food imported. For example, the GCC states account for half of the region’s yearly imports of meat, which is primarily consumed by the middle and upper classes.

These figures attest to the way that the Gulf states have used their purchasing power to manage their import dependence. Increasingly, they are not just using their wealth to import food for consumption but importing raw commodities for food production and even export.

Importing raw commodities and exporting refined products concentrates capital in the already capital-rich Gulf States. As a result, over the past two decades, some of these states have become exporters of food as well as importers. In 1991, the total food exports from the UAE were $9.4 million. By 2021 this number had grown to $14.9 billion, the highest in the Arab region. In 1991 Saudi Arabia’s foodstuff exports were $325 million. By 2021 they had risen to $4.1 billion.

The UAE, a country with almost no ecological base for large-scale agriculture, has a value of agriculture exports that is now greater than that of Egypt.

The scale of these exports relative to the major agrarian economies of the region is striking. The UAE, a country with almost no ecological base for large-scale agriculture, has a value of agriculture exports that is now greater than that of Egypt. This accumulation is the outcome of the Gulf’s position at the top of value chains. The ecological and social cost of food is paid for in the grower states, while processing, packaging and marketing ensures profit in the Gulf states.

The growth of the Gulf agribusiness sector has given the UAE and Saudi Arabia large shares of food markets in other Arab countries. For example, the value of Saudi Arabia’s dairy and cheese exports in 2018 was $1.4 billion.[6] In the same year, the UAE’s dairy product exports were almost $900 million. In 2020 the value of cooking oil, flour and sugar exports from the UAE was almost $700 million.[7]

Some of the poorer countries to which these exports are sent are themselves producers of the very same raw commodities—yet they buy the processed form from producers in the Gulf. For example, Sudan is a producer of raw sugar: In 2022 it exported $751 million in raw sugar to Spain. The same year it imported 25 percent of its sugar from the UAE.[8]

Land enclosures are a spatial fix that push the negative consequences of production onto one society while ensuring value can be accrued in another. The rupture of this land, its productive use value and in some cases spiritual and cultural significance is a deprivation. The extraction of agricultural resources from societies that suffer from malnutrition and high levels of food price inflation reflects the acute imbalance within the global economy and its manifestation in core-peripheral relations at the regional scale.

Aside from the immediate experience of dispossession and violence, these schemes also have secondary consequences that take their toll on society. These corollaries include food insecurity, high commodity prices and the cost of government food subsidies required for social stability.

[Christian Henderson is a lecturer in international relations and modern Middle East studies at Leiden University.]

Read theprevious article.

Read thenext article.

This article appears in MER issue 311 “Post-Fossil Politics.”

[1] Report: "Near East and North Africa – Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition 2022," FAO, 2023.

[2] Global Food Security Index 2022: "Qatar," Economist Impact.

[3] Abbas El-Zein, Samer Jabbour, Belgin Tekce, Huda Zurayk, Iman Nuwayhid, Marwan Khawaja, Tariq Tell, Yusuf Al Mooji, Jocelyn De-Jong, Nasser Yassin, Dennis Hogan, “Health and ecological sustainability in the Arab world: A matter of survival,” The Lancet 383/1 (2014), p. 458.

[4] Data available at the Land Matrix Database for 2023.

[5] Report: "Near East and North Africa – Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition 2022," FAO, 2023.

[6] World Bank: "United Arab Emirates Food Exports to World in US$ Thousand 1991-2021," World Integrated Trade Solutions (WITS).

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.