A Day as Ordinary as Any Other

Nathan Thrall's Newest Book Offers a Timely Window into Israel's Infrastructure of Occupation.

Nathan Thrall's Newest Book Offers a Timely Window into Israel's Infrastructure of Occupation.

A Review of Nathan Thrall, A Day in the Life of Abed Salama: Anatomy of a Jerusalem Tragedy (Metropolitan Books, 2023)

On a “cold, wet, and dreary day” in February 2012, a jack-knifed semi-trailer truck collided with a school bus carrying small children on the Jaba road, encircling the Palestinian city of the same name.

Originally a “bypass” road for Jewish settlers wanting to avoid Palestinian roads and populated areas, the Jaba road has become a vital throughway for Palestinians between the West Bank and Jerusalem after Israel built a bigger and better settler bypass. It winds its way just outside the Jerusalem municipal boundaries in what is known, under the Oslo Accords, as Area C—the 61 percent of the West Bank over which Israel has full control. As such, it falls under the jurisdiction of the Israeli traffic police and emergency services as well as the Israeli army. The Palestinian Authority, which nominally governs the West Bank, and its police and emergency services have no right of access to Area C without explicit permission from the Israeli military authorities.

The horrific accident, and the circumstances surrounding it, form the substance of Nathan Thrall’s new book, A Day in the Life of Abed Salama, named for the father of one of the children involved in the accident. The book (published October 3 by Metropolitan Books) is an elaboration of his much-lauded 2021 piece in The New York Review of Books. The full-length treatment, which is based on later, additional interviews with Abed Salama, his relatives and first-responders and takes instructive context-setting detours into the history of violence against Palestinians, is more ambitious and more clarifying. Thrall pulls off the difficult trick of distilling the extended tragedy of the Israeli occupation into this horrific event, compelling the large readership this book will likely generate, to reflect on the moral cost of our collective responsibility in allowing this indefensible situation to continue unabated.

“At rush hour, the Jaba road was clogged with a long line of Palestinian buses, trucks, and cars,” Thrall writes. As drivers approached a particular bottleneck, “some would overtake slow-moving vehicles by veering into a lane of opposing traffic. This had caused so many accidents that the artery came to be called ‘the death road.’”

A team of Palestinian health professionals on their way to work were the first to arrive on a scene they could initially barely comprehend: “a school bus flipped on its side, its doors against the ground, its front engulfed in flames.” Israeli soldiers at a nearby checkpoint were called upon to help by those present on the scene, but they stayed put. In a daze, Huda, a doctor on the team—who did not feature in Thrall’s original article—made her way to the burning vehicle and with the help of a bystander began pulling out whoever they could reach: the driver, teachers and children. They then provided first aid. Palestinian drivers rushed the injured to hospitals in Ramallah or, for those who had permission to enter, Jerusalem. Thrall recounts, “They were soaked and bone weary and there was nothing more for them to do. When a Palestinian ambulance finally arrived, most of the injured children had already been evacuated. Huda didn’t even notice it. The bus was still crackling with flames and there was much shouting and commotion. Not a single firefighter, police officer, or soldier had come.”

None would come until after Palestinians had already evacuated all the victims in their private cars. A Palestinian interior ministry official who happened to be passing by pled with two Israeli commanders he knew from previous interactions, seeking permission for Palestinian security personnel to take control of the area. He also requested West Bank families of the dead and injured be allowed entrance to Jerusalem and its hospitals. They granted his request, exceptionally, due to the severity of the accident and their acquaintance with him. Palestinian fire trucks arrived soon after and started putting out the fire. No ambulances or fire trucks from surrounding Jewish settlements showed up, and Israeli ambulances and fire trucks came only after the end of the fire and rescue operations. As one Palestinian rescuer ruefully noted, if Palestinian kids had been throwing stones, the place would have been swarming with Israeli soldiers within minutes.

The accident left six children and one teacher dead (the teacher having heroically saved the lives of several children). 46 more children were injured, as was the driver, who lost both of his legs. Most of the kids were from Shuafat—a refugee camp located inside annexed East Jerusalem but outside of Israel’s separation barrier, which residents working in Israel or East Jerusalem must pass through to get in and out of the camp.

Thrall uses this intimately recalled tale of tragedy and loss to expose the devastating impact on Palestinian lives of the vast infrastructural changes Israel has wrought in and around Jerusalem, which render the prospect of two states for two peoples, in his words, increasingly delusional. Indeed, elsewhere, Thrall has laid out his criticism of the two-state solution on both moral and practical grounds.

If Thrall’s account were a musical composition, it would perhaps be a requiem but fashioned in the form of a fugue, in which various interweaving threads take us deep into the lives of some of the principal characters. Yet Thrall always returns the reader to that one scene of a burning vehicle turned over on the side of a curvy two-lane highway slick from a heavy winter rain.

The reader learns about the accident and surrounding events only in fragments, as Thrall repeatedly delves into the lives of some of the dramatis personae: most prominently the title character, a man named Abed Salama, who Thrall came to know through his middle child’s babysitter, a cousin of Abed’s niece. (Thrall—who I have known for several years—is a US journalist based in Jerusalem and has covered political violence in Palestine/Israel for years, including for almost a decade as a senior analyst and project director for my organization, the International Crisis Group.)

Abed’s four-year-old son, Milad, was on the bus that crashed on a school trip. His family lives next to Shuafat camp in Anata, a town that is split in half, divided between the occupied West Bank and annexed East Jerusalem. Because Abed is a West Bank resident, he is not permitted to enter Jerusalem. But since the wall is located outside of town, enclosing its Palestinian population in the West Bank, he crosses daily into Israel simply by going to a nearby store.

The morning of the accident, Abed was at the butcher’s when he heard about a terrible crash involving a school bus. Not knowing whether his son was on it, but fearing the worst, he was immediately overcome by guilt over an unrelated event in his past: His decision years earlier to abruptly divorce his first wife, whom he had married, unhappily, after he could not wed his high school sweetheart. In his feverish imagination, he now cast his child’s possible fate as a kind of retribution for this self-ascribed misdeed. Details such as these, which were not included in Thrall’s original article, bring the story to life in a way that an exposition of events alone never could.

Thus, riding with him on his memories, the reader suddenly finds themself in an entirely different frame. It is the world of Palestinian society, like any ordinary society with all its friendships, romances, jealousies, family feuds and reconciliations. The situation is, of course, not ordinary, as Palestinian society labors under an Israeli military occupation, which generates daily, often highly antagonistic interactions between Palestinians and their Israeli occupiers.

Indeed, the story of Abed’s life is also the story of the countless ways Israel has incrementally pushed Palestinians out of Jerusalem and restricted their access to the city, for example to visit the Aqsa Mosque or go for treatment at Makassed Hospital. Abed has learned to navigate this labyrinthine system of domination-through-separation.

...the story of Abed’s life is also the story of the countless ways Israel has incrementally pushed Palestinians out of Jerusalem and restricted their access to the city...

Abed Salama’s was born in 1969 in Anata. He came of age with the outbreak of the first Palestinian intifada in late 1987 and was recruited in one of the resistance groups, the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine. As a member, he organized protests, recruited new members and distributed bayanat. In that capacity, he repeatedly faced off with people, including relatives from the neighborhood, active in other groups, especially Fatah—the main constituent of the Palestine Liberation Organization. By digging deeply into the principal character’s past, Thrall is able to provide a historical background to his story and show how the evolving violence structures everyday occurrences in ways big and small. Through Abed, he describes the major changes wrought in and around annexed East Jerusalem by international politics and Israeli strategies of dispossession, Palestinian resistance to the occupation and intra-Palestinian rivalries. He also captures the tensions between Palestinian families expelled from their land, now living in Shuafat camp, and those who were able to stay, for example in adjacent Anata; Abed and his friends viewed the camp, which was rife with drug-related crime, as a prime target for Israel’s recruitment of collaborators, the bane of the national resistance movement.

A second life Thrall explores belongs to Huda, the Palestinian doctor who happened upon the road accident with her colleagues. Through Huda, Thrall takes the reader to the 1948 Nakba and its aftermath, when her family was driven from their Haifa home into a Syrian refugee camp. From there, readers get a snapshot view of the history of the Palestinian national movement and its transnational reach: from a Syrian refugee camp to the PLO’s heyday in, then expulsion from, Beirut, to Israel’s bombing of the PLO’s Tunis headquarters in 1985 and on to Ramallah, where surviving Palestinian leaders moved after the signing of the Oslo Accords. Each of these episodes is based on what Huda has heard from her parents or personally experienced. Her recounting of the aftermath of the 1985 Tunis bombing is particularly striking as it foreshadows the horrible fire she will witness at the site of the bus crash almost three decades later. Fresh out of medical school, Thrall writes, she rushed to the scene, where she found “a hellscape of wreckage, ash, and bodies… The putrid smell of death was everywhere.” More than sixty Palestinians and Tunisians were killed in the attack.

Ultimately, where the stories, lives and perspectives converge is in Jerusalem itself. And Thrall highlights the many techniques the Israel state has used to increase its presence in Jerusalem to strengthen its claim to the city.

Abed’s brother, Nabeel, for example, holds a green identity card, marking him as a resident of the West Bank and rendering him unable to live in the areas annexed to Jerusalem. As a result, he and his wife reside in Anata. Nabeel’s wife, however, holds a blue ID, as a Jerusalem Palestinian. In order to retain this ID, the couple has to maintain an apartment in Dahiyat a-Salaam (a neighborhood in annexed East Jerusalem). Thrall, whose writing is suffused with an unshakeable humanity, brings out the cruelty of it all: “For the crime of living with her husband just down the road, she could be cut off from the rest of her family and the city in which she had been born and raised.”

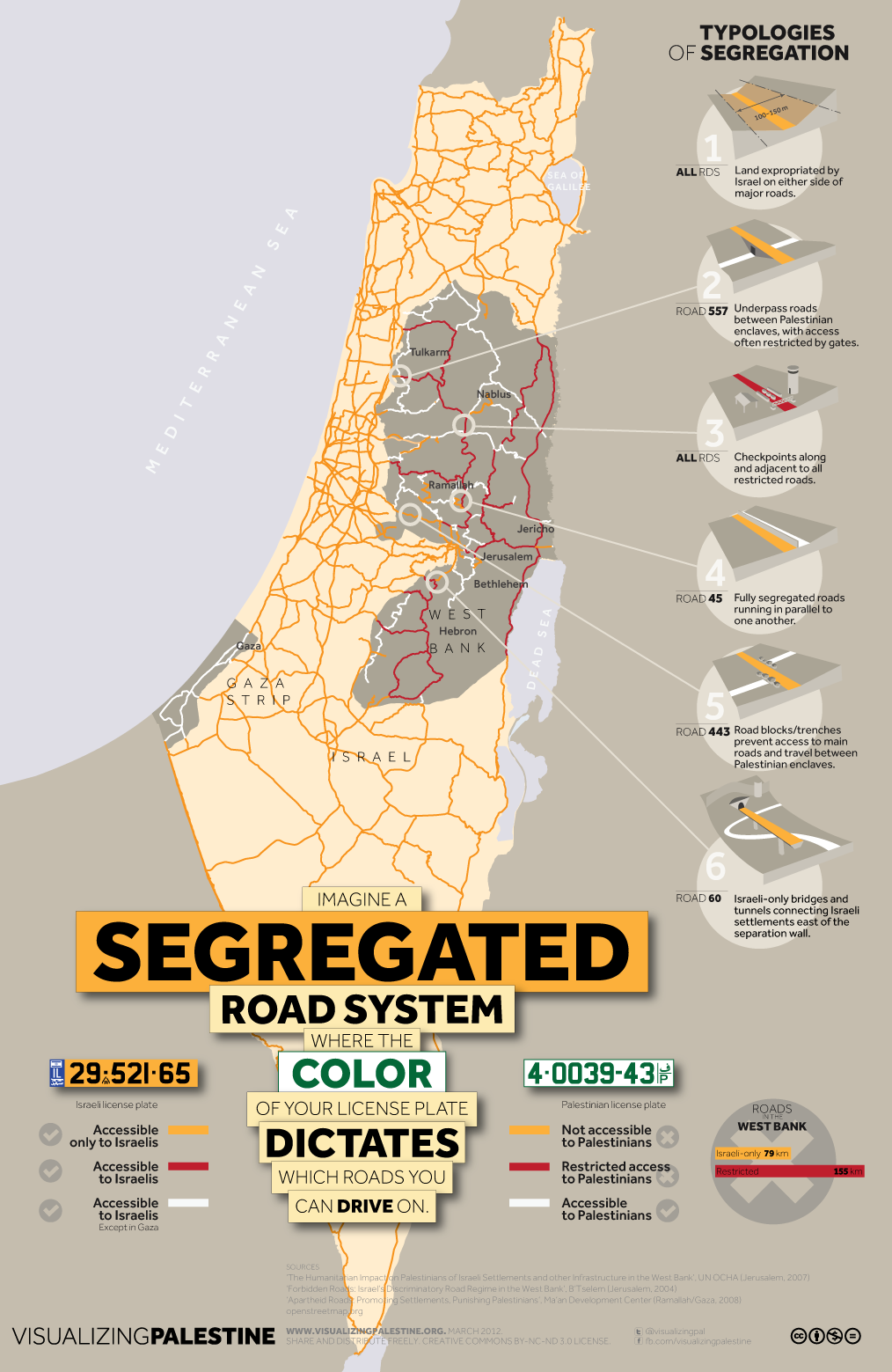

Added to the use of differential identity cards are the different license plates, movement restrictions through checkpoints, settler bypass roads, home demolitions and an intricate permit system that allows for Palestinian construction in ever-diminishing restricted areas or gives selected West Bank Palestinian workers temporary access to Jewish settlements to perform manual labor. And, of course, there is the separation barrier itself, which not only divides Palestinians but also expropriated a large chunk of their land when it was erected.

The situation is enormously complex. But, as Thrall’s book illustrates, its complexity is the point. The more difficult to successfully navigate it, the greater the chance that Palestinians will simply give up, pack their bags and seek a better life elsewhere, forfeiting their right of residence in their homeland in the process. Indeed, the book has several other threads, offering the perspectives of Palestinians and Israelis who play roles in this tale. Together these combine into a story of great political import.

A Day in the Life takes its start from a day as ordinary as any other. But it ends up recounting events that are extraordinary mainly because of what they say about the extreme nature of Israel’s longstanding effort to confine and dispossess Palestinians. The book arrives at a particularly pertinent moment, namely Israel’s steady drift toward the far-right of the political spectrum and the ensuing escalation of this effort. (Between writing this review and its publication, this escalation has exploded into an Israeli declaration of all-out war against Hamas in Gaza in the wake of the October 7 attack by Hamas inside Israel.) Thrall crystallizes these developments as part of a long and at times violently banal trajectory, showing how the dehumanization of Palestinians holding onto their land extends to providing no aid when ordinary people are caught up in a horrible, but not particularly unusual, highway crash.

[Joost Hiltermann is the Middle East & North Africa Program Director at the International Crisis Group.]