Manufacturing the AKP in Turkey

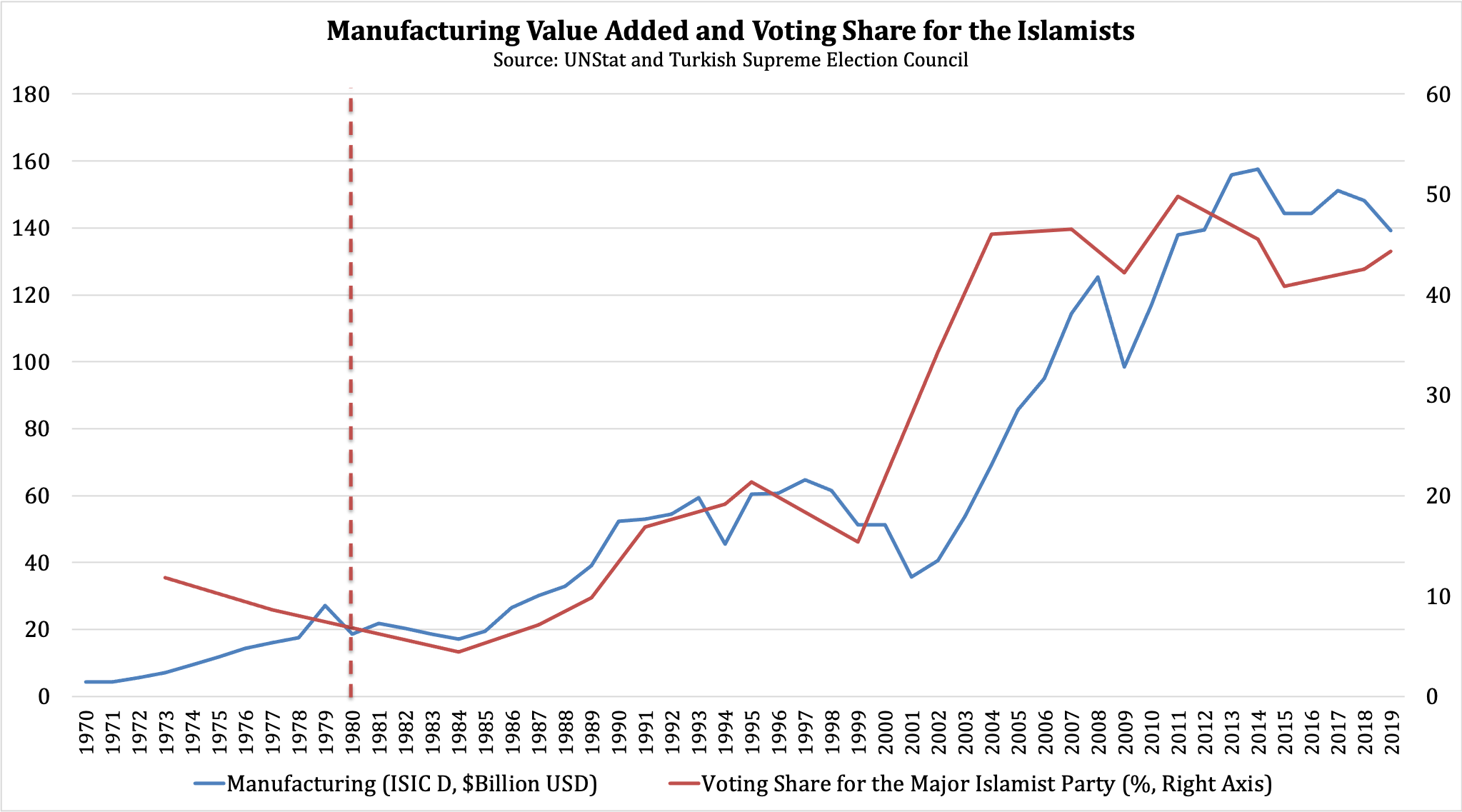

The AKP's decades-long electoral success in Turkey has been made possible by their strategic alliance with the country's small industrialists. Utku Balaban analyzes the connection between Islamism and industrialization since the rise of these urban manufacturers in the 1980s and explains the nuances