Shifting Approaches to Women and Gender in Labor, Politics and Society

It took MERIP some five years and 50 issues before it finally addressed women and gender in its pages. In August 1976, the two feature articles explored questions about working women, my own “Egyptian Women in the Work Force” and “The Proletarianization of Palestinian Women in Israel” by Najwa Makhoul (using a penname). Over the following four decades, MERIP would continue to engage women’s issues and eventually also gender issues, at least from time to time. As a historian, I cannot resist trying to periodize this engagement. Based on a review of issues from 1976 to 2016, MERIP’s coverage of women and gender can be divided into five periods that track both intellectual turns in the academic field of women’s studies and the changing political context of regional developments.

In the first period, the decade from roughly 1976 to 1986, most pieces related to women focused on the political economy of women’s work. Authors pursued questions about women’s presence and status in the labor force, past and present—how women’s work had been shaped by the particularities of capitalist development in colonial settings and overall shifts in the global economy, and the differential effect on women of mass labor migration. These contributions include Judith Gran’s “Impact of the World Market on Egyptian Women,” Mona Hammam’s “Textile Workers of Shubra el-Khayma,” Fatma Khafagy’s “Women and Labor Migration,” Elizabeth Taylor’s “Egyptian Migration and Peasant Wives,” Linda Layne’s “Women in Jordan's Workforce,” Erica Friedl’s “Women and the Division of Labor in an Iranian Village” and Cynthia Myntti’s “Yemeni Workers Abroad.”

Just in case the less sapient reader might miss the guiding ideology here, that first issue on women in 1976 opened with a quotation from Frederick Engels tying the patriarchal household to changes in the mode of production. (I have to take responsibility!) This self-consciously materialist approach to women’s oppression deliberately eschewed the standard cultural and religious explanations for the plight of Middle Eastern women. Certainly, this first period of MERIP’s foray into women’s studies was aligned with the interests of neo-Marxist academics of the time and deeply inflected by a rapid opening of the region to a world market with the resulting increase in the waged working class in agriculture and industry, and regional labor migration.

This self-consciously materialist approach to women’s oppression deliberately eschewed the standard cultural and religious explanations for the plight of Middle Eastern women

Next up was the centering of questions about the ways in which women, hitherto little visible in studies of political movements in the region, had been and continued to be key political actors. Beginning in 1986, the issue of Middle East Report devoted to “Women and Politics in the Middle East,” inaugurated a period of exploration of women’s contributions to various political movements and moments. This first issue foregrounded women in the Palestinian movement (Julie Peteet), the Iranian Revolution (Mary Hegland) and Egyptian uprisings of the nineteenth century (Judith Tucker), all framed by Suad Joseph’s reflections on how women participate in states, movements, revolts and revolutions.

Occasional articles about women and politics over the next few years culminated in another full issue in 1991 on “Gender and Politics.” (This issue was not the first use of gender as a concept in MERIP’s pages—that honor belongs to Marilyn Booth, as far as I can determine, in an article she wrote on women’s prison memoirs for an 1987 issue devoted to human rights.) The gender and politics issue did signal a conceptual shift, however, or at least an expanded framing. Articles on the gendering of public political space in Yemen (Sheila Carapico), the state and its mediation of Islamic gender norms (Deniz Kandiyoti) and the role gender imaginings played in the Gulf War when it came to Iraqi masculinity (Anne Norton) were situated by Julie Peteet and Barbara Harlow in the context of the role gender plays in political transformations.

Women, gender and politics remained a hardy perennial throughout MERIP’s history, although arguably the period between 1986 and 1994 marked the most intensive engagement with women’s participation in political movements and state projects. MERIP coverage in this period reflected an expansion of women’s studies into gender studies more broadly, as well as a growing awareness of the critical role women had played in political movements from the Palestinian Intifada to the long-unsettled aftermath of the Iranian Revolution.

A third period, from roughly 1994 to 2003, is characterized by a proliferation of sites for the study of women’s and gender issues. Population policies and demographic trends, and the implications for women’s roles in family and society, were featured in a 1994 issue devoted to “Gender, Population, Environment.” It included articles on official uses of Islamic ideology in Iran (Homa Hoodfar), Egyptian state policies (Cynthia Lloyd, Barbara Ibrahim, Laila Nawar) and overall patterns of demographic change in the region (Youssef Courbage). The 1996 issue on “Gender and Citizenship in the Middle East” took a close look at the gendering of the rights and entitlements of citizenship—in Kuwait (Haya al-Mughni), Palestine (Penny Johnson, Islah Jad and Rita Giacaman), Israel (Nitza Berkovitch), Turkey (Yesim Arat) and Algeria (Boutheina Cheriet), with Suad Joseph providing an overall introduction.

LGBTQ issues moved to the fore in 1998 with “Power and Sexuality in the Middle East,” which included essays by Walter Armbrust and Garay Menicucci on sexuality in Egyptian film as well as articles about honor killings in Palestine (Suzanne Ruggi) and tensions between Zionism and lesbianism in Israel (Yael Ben-zvi). A programmatic piece on “queering” the study of the Middle East by Bruce Dunne introduced the issue. The 2001 Middle East Report on “Culture and Politics” included two gender pieces, one by Ziba Mir-Hosseini on Iranian cinema and its contestation of fiqh-based gender relations and another by Linda Herrara on how “downveiling” reflected cultural contests in Cairo streets. MERIP was coming to terms with the ubiquity of gender as a research lens. And, in addition perhaps, there was a sense of stasis in the region that deflected attention from political action and encouraged researchers to look more closely at other sites of contestation.

The US invasion of Iraq in 2003, which marked an aggressive upturn in American involvement in the region, ushered in a fourth period in which empire and its effects moved to the fore. The 2006 issue “Dispatches from the War Zones,” about Iraq and Afghanistan, featured articles by Huda Ahmed that studied the ways in which the new “democratic” political system in Iraq had disappointed women and, indeed, as Nadje Al-Ali and Nicola Pratt reported, almost totally disempowered them. Al-Ali and Pratt would revisit this topic in early 2011, with a disturbing piece on escalating violence against Iraqi women while Farzaneh Milani contributed a piece in 2008 on the imperial discourse of “captive women” to be saved and freed. The rhythm of coverage slowed between 2003 and 2013: Every second or third Middle East Report might contain a single piece related to women’s and gender issues. Some of these addressed protesters in Iran, Palestinian women in the Israeli Knesset, struggles in Turkey for full citizenship, women in the cabinet of Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and challenges for women at Iraqi universities. Readers had to wait until fall 2013 for another dedicated gender issue to appear. It may be that the violence, displacements and other costs of empire during this time limited women in ways that did not inspire researchers or editors to move much beyond women as victims.

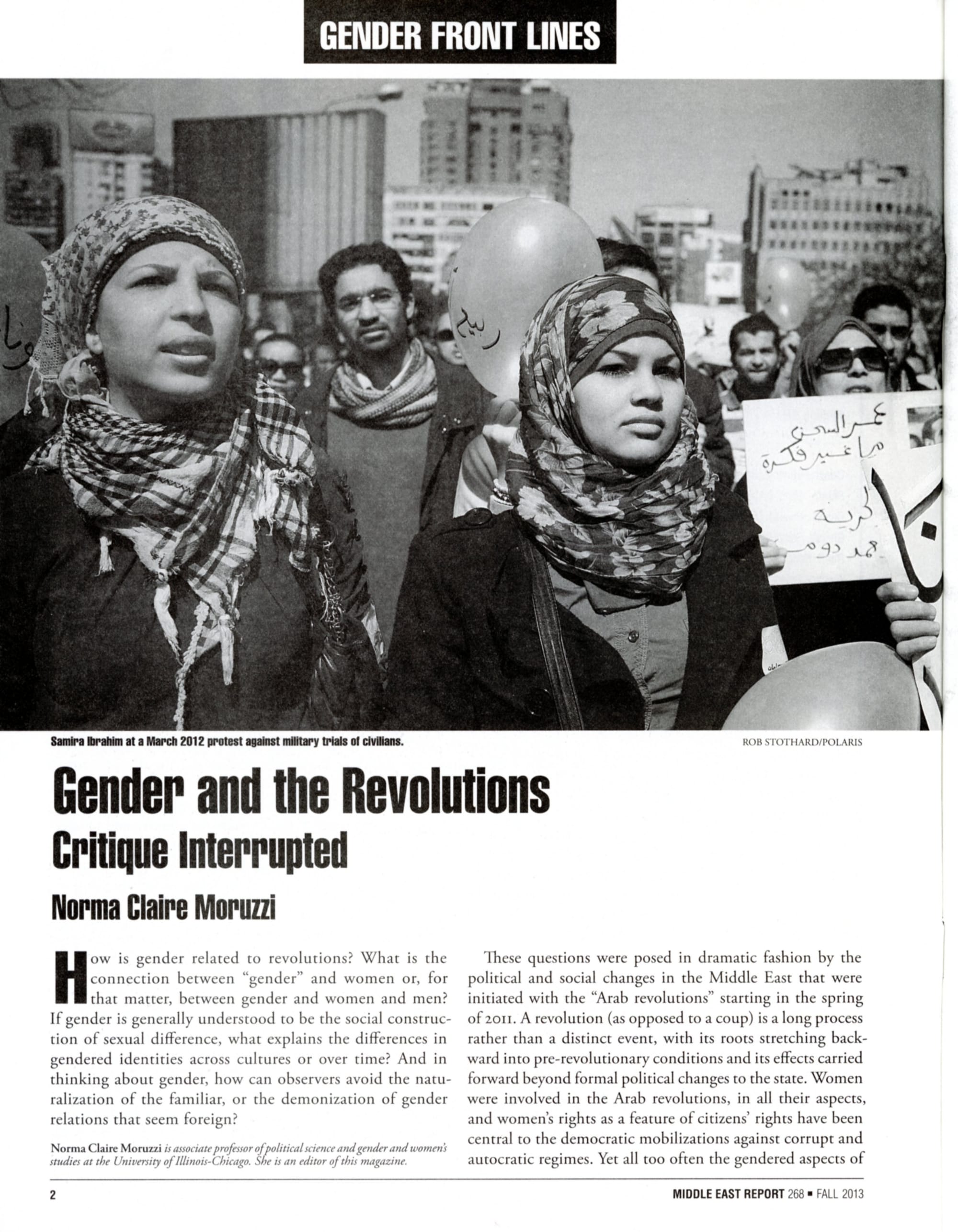

Finally, the role of women and gender in revolutions and popular movements came predictably to the fore after 2011 as we all grappled with the meaning and significance of uprisings in the region and the counterrevolutions that followed.

Finally, the role of women and gender in revolutions and popular movements came predictably to the fore after 2011 as we all grappled with the meaning and significance of uprisings in the region and the counterrevolutions that followed. Here MERIP did not disappoint. Published in 2013, the issue “Gender Front Lines” brought together five strong pieces that honored the role of women in the uprisings and addressed the complexities of gender—masculinities as well as femininities—as they played out during the 18 days of revolution (and counterrevolution) at Tahrir Square in Cairo (Mervat Hatem and Vickie Langohr), as well as in Syrian television dramas (Rebecca Joubin) and the Gezi Park protests in Istanbul (Neslihan Sen). Norma Claire Moruzzi addressed Tunisia and other cases in her essay “Gender and the Revolutions.” I have assigned this issue to undergraduate students repeatedly as one of the best ways to acquaint them with the roles women played and the obstacles they faced as well as how gender can work to destabilize power or be used to reinvigorate it. It represents how MERIP has engaged women’s and gender studies on its best days, bringing together key scholars in the field to cut through obfuscations and offer analysis that engages and empowers its readers.

[Judith Tucker is professor of Middle East history at Georgetown University and a long-time member of the MERIP community.]