Capturing the Complexity of Lebanon’s Civil War and Its Legacies

The current political and economic crises in Lebanon reveal the myriad ways that the Lebanese continue to deal with the aftereffects of the 1975–1990 civil war. The roots of many of today’s crises—a collapsing currency, shortages of basic goods like medicine, fuel and electricity, rising poverty and government paralysis—can be traced back to wartime structures and the political settlement that institutionalized them.

American media coverage often suggested that the Lebanese civil war was precipitated by pre-modern religious hatreds and viewed human suffering through the filters of US and Israeli foreign policy. The focus on dramatic events, sensational images and the statements of self-appointed sectarian leaders, buried the complexity of a multi-layered series of local conflicts—including their roots in a political economy marked by severe social and geographic inequality. In contrast, MERIP’s commitment to foregrounding local social struggles and their links to the global political economy, along with a sensitivity to historical context, has provided a powerful antidote to mainstream reporting and analysis. The resulting archive remains a valuable resource to students of Lebanon and the region.

Well before the onset of the civil war, MERIP authors reported from an increasingly turbulent Lebanon. They foregrounded the perspectives of those Lebanese—the majority—who were marginalized within the country’s illiberal market economy and highlighted how they came to see their interests as aligned with those of the Palestinian National Movement and larger anti-imperialist struggles. Indeed, several founding members of MERIP had traveled to Beirut (and Amman) in the summer of 1970, and upon their return to the United States took part in the October meeting that led to the organization’s establishment. From the beginning, representatives from the Beirut-centered Arab New Left, such as Fawwaz Traboulsi, appeared as contributors and in interviews as newsmakers in their own right.

Reading back through MERIP’s coverage of Lebanon, the reader gets a clear sense of how the 1975 outbreak of the civil war was very much a product of overlapping historical dynamics. The writing is detailed, strongly analytical and often prescient. For example, in the wake of the 1973 clashes between Palestinians and the Lebanese army, with their Phalangist militia allies, Samih Farsoun wrote an extensive report titled “Student Protests and the Coming Crisis in Lebanon.” He outlined the contradictions of Lebanon’s political economy that generated vast inequalities and how those inequalities contributed to growing tensions and violence. Specifically, he explained how the Lebanese economic and political system privileged non-productive sectors like tourism, trade and finance over labor-intensive agriculture and industry and concentrated power in a narrow elite and associated clergy. Due to these factors, the Lebanese order was extremely fragile in the face of internal pressures and was unable to weather regional and global storms.

These arguments provided the context for MERIP’s reportage in the article “Lebanese Fascists Attack Palestinians” about the Kata’eb’s infamous 1975 attack on a busload of Palestinian and Lebanese civilians; an event which, for many observers, marked the beginning of the war. The next year, MERIP Reports published issue 44, “Lebanon Explodes,” which provided detailed analyses of the initial phase of the conflict (referred to as the Two-Year War) and the historic transformations—primarily local but regional as well—that led up to it. Farsoun’s contribution explored how new political and economic structures evolved as the war progressed and as alliances formed and solidified, first with the war of right-wing Christian forces on the Palestinians, then on the leftist non-sectarian alliance known as the Lebanese National Movement (LNM). His analysis, like that of Michel Kamel in the same issue, foregrounded the emerging social struggle of working people and peasants against the entrenched power of the notable families both prior to the outbreak of war and throughout its early phases. While Kamel’s analysis stressed the regional and global linkages, both were prescient in that they recognized early on the strong possibility that counter-revolutionary interests would pursue the division of Lebanon into sectarian enclaves, and they anticipated the emergence of a war economy that would underwrite the forces of destruction for more than a decade.

Nowhere were these overlapping contradictions, and the transformations they wrought, more evident than in the experience of Lebanon’s Shi’a. Salim Nasr’s 1985 article “Roots of the Shi’i Movement” traces their path from marginalized communities to dynamic political forces on the eve of the civil war. Driven by economic and ideological transformation in the south and growing migration to Beirut and overseas, the Shi’a developed an “active and radicalized intelligentsia” that combined with other new strata to challenge the distribution of power and resources in the country.

Throughout the civil war, MERIP remained committed to exploring its complexity. The coverage included interviews and profiles of an array of prominent political leaders including Progressive Socialist Party head and LNM leader Kamal Jumblatt, the Nasserite Ziad Hafez, Communist George Hawi and even the leader of the fascist anti-Palestinian Guardians of the Cedars movement Abu Arz. These, together with MERIP’s in-depth field reports and articles authored by Lebanese writers and scholars, encouraged MERIP readers to develop nuanced understandings of postcolonial Lebanon and the socioeconomic transformations that drove the country toward war.

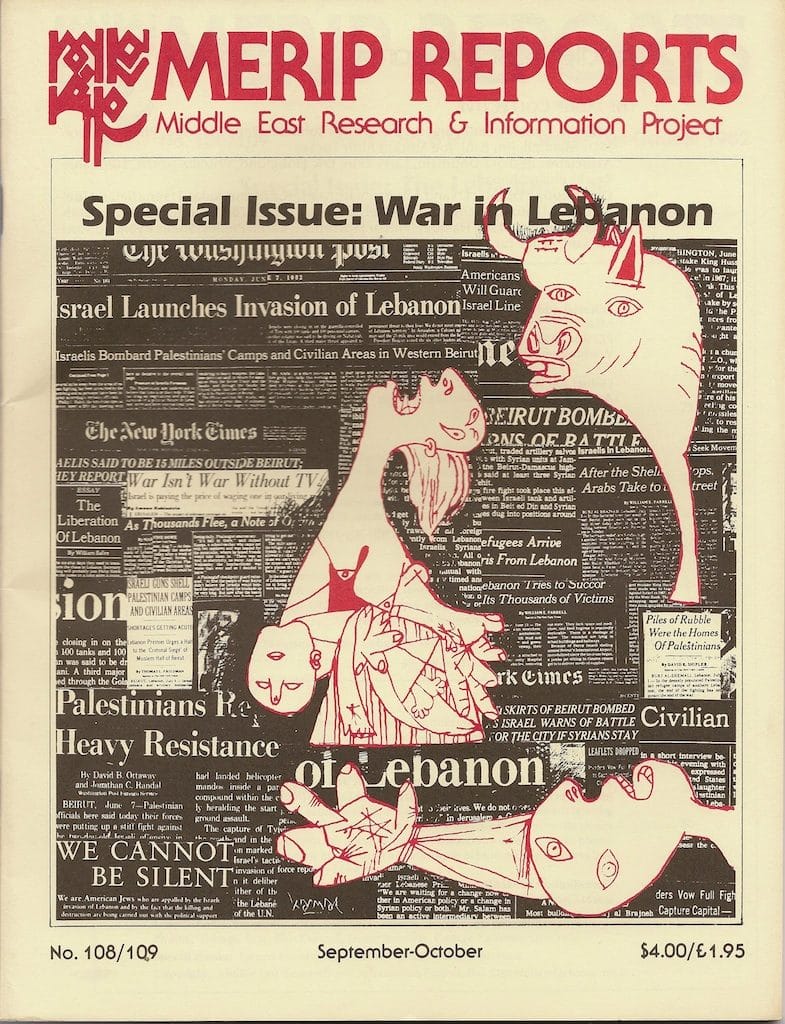

Further, MERIP connected these developments to regional dynamics that emerged from Palestinian resistance to Israeli colonization, the Arab Cold War and the Iranian Revolution, all within the larger bipolar world order. It is a credit to the editors and the writers—activists, journalists and scholars alike—that MERIP was able to capture and explain such complexity all without losing sight of the human experience and toll of war. To guide general readers, MERIP produced occasional overviews and primers. After Israel’s 1982 invasion, Joe Stork and James Paul wrote the primer “The War in Lebanon,” followed in 1983 by Stork’s extensive “Report from Lebanon” based on his recent visit. In 1985, Tom Russell’s “A Lebanon Primer” provided detailed and concise summaries of Lebanon’s increasingly complicated conflicts. With the end of the war and the benefit of hindsight, MERIP assistant editor Martha Wenger (responsible for many primers over the years) put together the very informative “Lebanon’s 15-Year War, 1975-1990,” which provided a comprehensive overview of the different local, regional and global interests and remains a useful starting point for readers interested in the civil war today.

As the dynamics of the conflict gave rise to new leaderships and movements, sectarian discourse seemed to eclipse social struggle as a primary driver of the war. MERIP writers, however, rightly reminded their audience that sectarianism is not an unchanging cultural norm but rather a social construct tied to material interests and power relations. MERIP’s coverage of conflicts within Lebanon’s Shi’i communities, for example, captured the processes by which sectarian politics came to eclipse other possibilities. The onset of the war and especially the horrors of the 1978 and 1982 Israeli invasions and the brutal occupation of the largely Shi’i south broadened existing mobilizations and deepened already emergent socioeconomic divisions within Shi’i communities. James A. Reilly’s “Israel in Lebanon, 1975-1982” shows how the largely nouveau-riche leadership of Amal had by 1982 already moved away from the working class and peasant-based Movement of the Dispossessed, which was responsible for much of the pre-war mobilization of the community. Its tenuous relations with the LNM and its decision to stand aside in 1982 and allow Israel to punish the Palestinians in the south, further alienated many left-leaning Shi’a. That decision and Amal’s brutal attacks on Palestinian civilian centers that came to be known as “the War of the Camps,” opened the way for Islamic Amal, a precursor to Hezbollah, to siphon off Amal members in a quest to build an explicitly faith-based movement.

MERIP writers rightly reminded their audience that sectarianism is not an unchanging cultural norm but rather a social construct tied to material interests and power relations.

Although rivals, Amal and the emergent Hezbollah together challenged not only the Israeli occupation. As they grew stronger, they waged war on the secular leftist parties of the LNM, which led the early resistance to Israeli occupation and boasted large Shi’i memberships. At the same time, they challenged the power of the established notable families of the south. The victory over ideological rivals for the loyalty of Shi’i workers and peasants underscores the fact that the emergence of sectarian parties and militias in Lebanon was not the product of an imagined primordialism but of people engaged in concrete struggles for political and economic power.

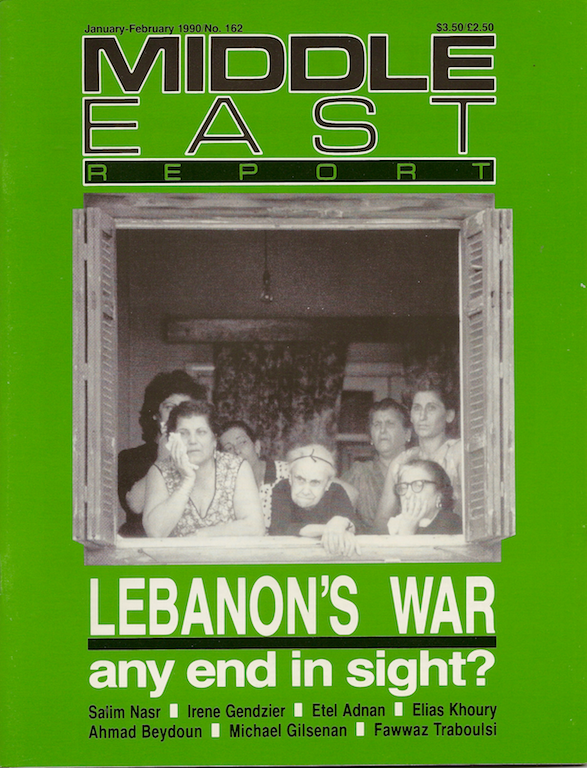

In early 1990, MERIP published one of its more notable issues about Lebanon, entitled “Lebanon's War: Any End in Sight?” It included Wenger’s primer, an interview with novelist Elias Khoury, a powerful poem by Etel Adnan titled “It Was Beirut, All Over Again” and a series of reports about the political dynamics of what was—for most Lebanese—the last and very destructive phase of the conflict. (For those in the occupied south, of course, the war continued until the Israeli military was driven out in 2000.) The reports highlight the value of MERIP’s political economy approach to the Lebanese war and prefigure much of the literature on the political economy of civil wars that emerged in the decade following the fall of the Soviet Union. Two articles in particular, Salim Nasr’s “Lebanon’s War: Is the End in Sight?” and Nazih Richani’s “Class Formation in a Civil War,” identified a shift in the nature of the war. In the first phase until 1982, the costs of the war were absorbed by Lebanese government reserves, the fortunes of the wealthy, the economic power of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) economy and growing remittances from Lebanese working in the Gulf. But with the division of Lebanese territory into confessional enclaves, the consolidation of the Syrian occupation and the destruction inflicted by the Israeli military, the Lebanese conflict was transformed. The war became a politico-economic system in which evermore predatory militias pursued economic agendas and were increasingly able to capture state institutions to protect and further their self-serving goals.

Due to its unique approach to the war MERIP was better placed than most, with the possible exception of the now-defunct Middle East International, to help readers understand how wartime structures came to shape the political economy of Lebanon’s postwar reconstruction. Salim Nasr’s retrospective overview of the economic processes that enabled the continuation of the war laid the groundwork for critical analyses of the reconstruction and its multiple failures. Fawwaz Traboulsi’s “Confessional Lines” rightly suggested that the Ta’if Accords, which ended the civil war, did little to rectify the political and economic inequalities that brought the war about in the first place and institutionalized the sectarianism that insulates elites—and the system as a whole—from accountability.

In the 1990s, as Lebanon’s war fell out of the headlines in the United States, the toxic nexus of sectarian politics and merciless market ideology that brought about the war now shaped the era of reconstruction. The contradictions, however, now played out within a regional and global context changed by the fall of the Soviet Union, the seeming triumph of finance-driven market capitalism and an era of increased intervention in the region by the United States. Indeed, Etel Adnan’s poem “It was Beirut All Over Again” might be read as a lamentation for social imaginaries, solidarities and political possibilities that were eclipsed by 15 years of violence. Traboulsi, following a grim analysis, sought hope for the future in the youth and the slim possibility that a post-war civil society might emerge to engender a true democracy.

In the 1990s, as Lebanon’s war fell out of the headlines in the United States, the toxic nexus of sectarian politics and merciless market ideology that brought about the war now shaped the era of reconstruction.

Such hopes were frustrated. The 1997 special issue “Lebanon and Syria: The Geopolitics of Change” took stock of Lebanon’s reconstruction under the economic tutelage of the international financial institutions (IFIs) on the one hand and the political control of Syria on the other. Volker Perthes’ “Syrian Involvement in Lebanon” and “Myths and Money” analyzed the regional constraints on reconstruction and the failures of the market model imposed by the IFIs and their allies among Lebanon’s financial elite. Saree Makdisi’s “Reconstructing History in Central Beirut” provided a powerful analysis of the elite’s failed efforts to reconstitute the myth of the Merchant Republic as the basis for a new neoliberal polity and national identity.

Just as MERIP’s focus on material conditions illuminated the origins of the conflict, this approach also revealed how they contributed to its longevity. Moreover, those analyses outlined the contours of the post-conflict political economy with a clarity absent in mainstream reporting, to say nothing of multiple studies by the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and a host of international aid agencies. In this way, MERIP authors exposed the idea of market-driven reconstruction as bankrupt and warned of the rise of a new illiberal polity. As the last several years have demonstrated with painful clarity, this polity has in fact arisen, and today cannot escape the logics of war or hope to achieve a positive peace.

[Najib Hourani is an associate professor of anthropology and Global Urban Studies at Michigan State University and a member of MERIP’s editorial committee.]