Understanding the Diversity of Political Islam

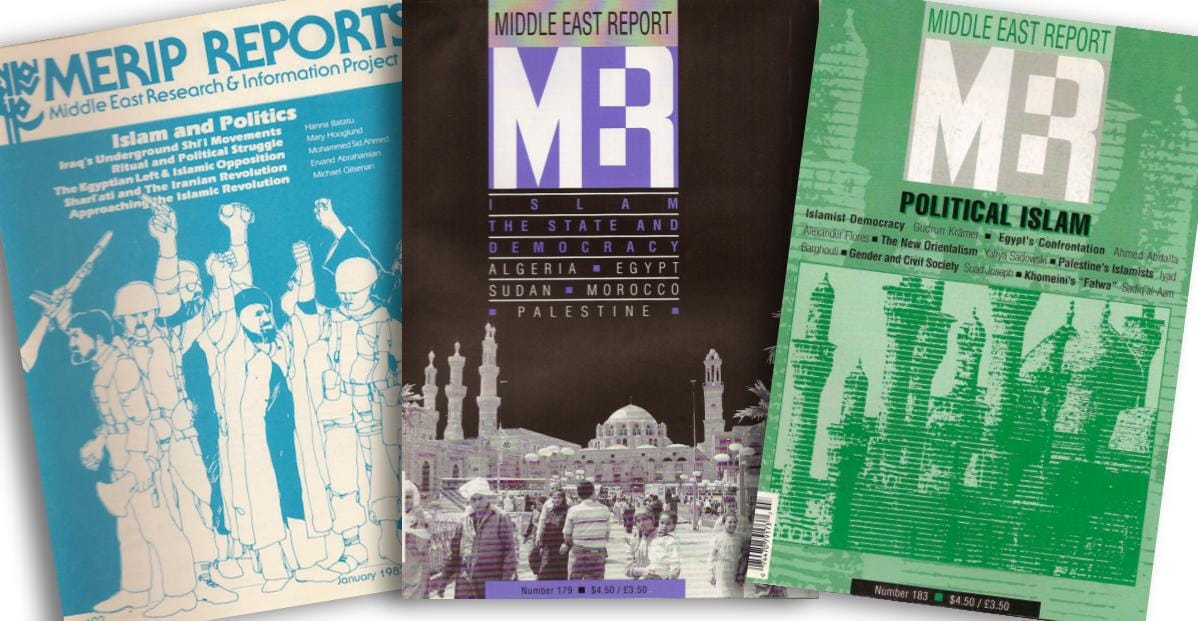

Francesco Cavatorta examines MERIP's 50 years of covering the complex phenomenon of political Islam and finds that much of it is based on field research, participant observation, interviews and ethnography. The result has been a rich diversity of approaches that comprehend the plural nature of Islam