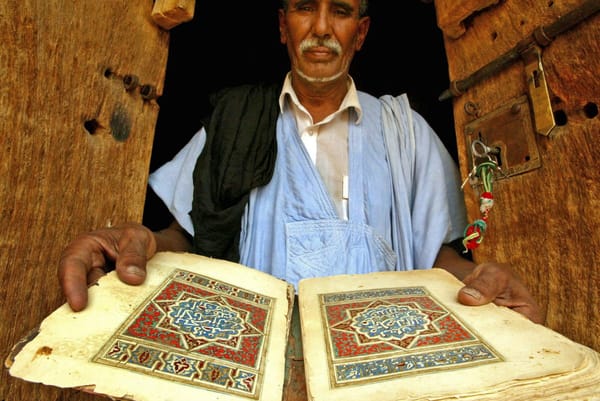

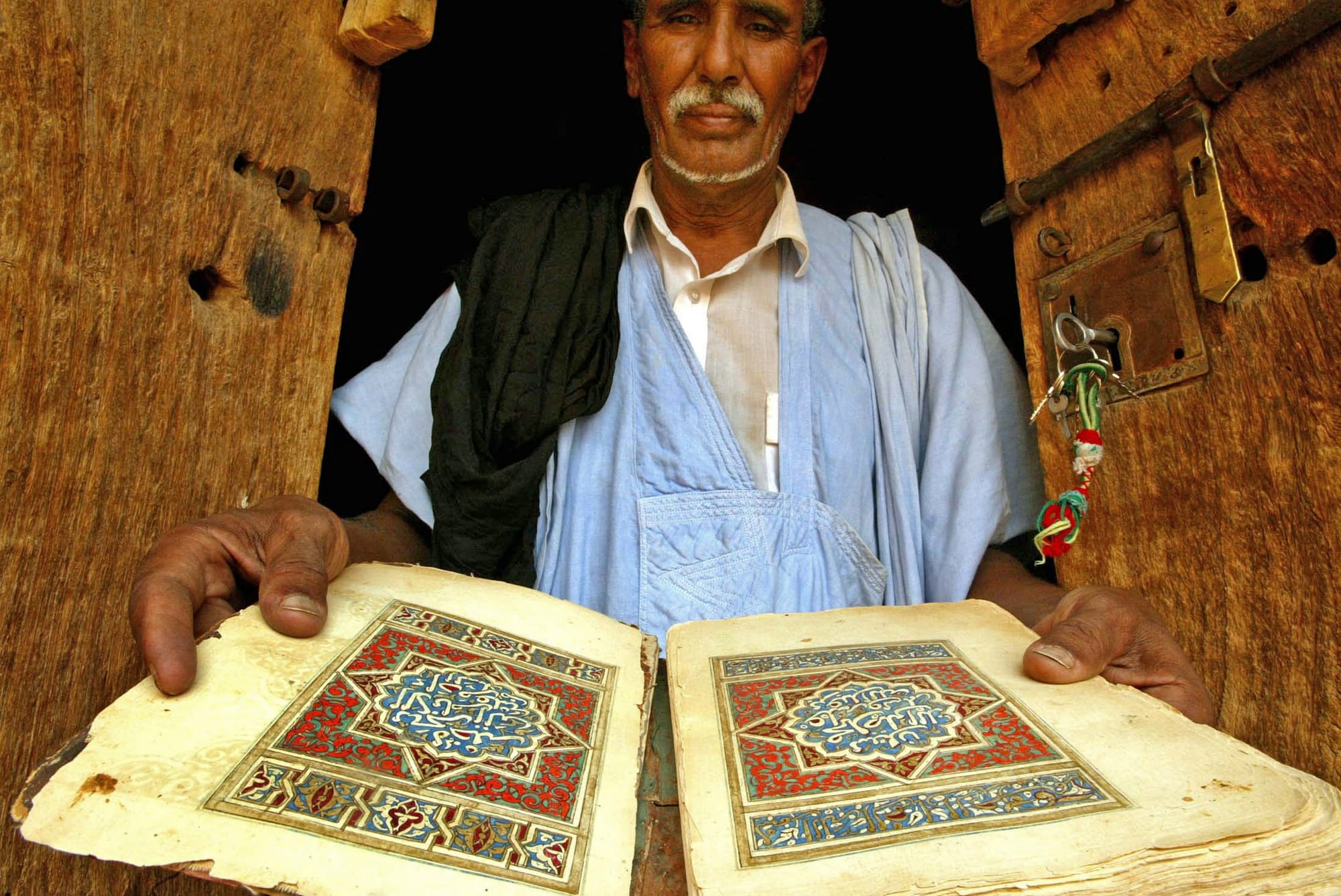

The Importance of Mauritanian Scholars in Global Islam

The North African nation of Mauritania may be peripheral in global affairs, but its robust network of Islamic scholars is central to transnational Islamic movements and ideas. Zekeria Ould Ahmed Salem traces the influential political economy of Mauritanian Islamic scholarship that has both bolstered